“…seeing this elegant Piece of Antiquity has been so very much taken notice of, by almost every Antiquary and Historian that have ever treated of the Affairs of Scotland, I shall therefore give as ample and satisfactory an Account of it, as I can……..” (A Gordon, Itinerarium Septentrionale, 1726).

Introduction

In 1968 the characteristic turreted, crow-stepped, steeply-roofed old Scottish Baronial mansion of Stenhouse in East Stirlingshire was torn down, a derelict shell long forsaken by the Bruce family who had occupied the surrounding lands for centuries. Stenhouse “Castle”, as it was invariably known to the inhabitants of its adjacent community of Stenhousemuir, had been built, presumably the last in a series of previous family seats, in 1622 by the 1st Baronet. The name Stenhouse or Stonehouse occurs in several other Scottish localities, but this particular one derived its name from a very specific “stone house.”

In a decade which saw an escalation of the post-war demolition of historic buildings throughout the country, this particular area could claim an unenviable precedence of very long standing, something of a heritage of vandalism. Sir Michael Bruce of Stenhouse, 6th Baronet, had been responsible, over two hundred years earlier in 1743, for the destruction of the far more significant structure known as Arthur’s O’on, which had stood in the vicinity for well over a thousand years before any Bruce had ventured upon the site. Not long after the demise of the O’on, the Industrial Revolution altered the surroundings far more profoundly and lastingly when Carron Company established their renowned iron works on the banks of the River Carron below, on land feu’d from that same Sir Michael Bruce of Stenhouse. The length of time that elapsed between the demolition of the O’on by a Bruce, and the visiting of the same fate by Carron Company, in due course, upon the Bruce family mansion, perhaps renders any sense of irony inadmissible.

The 18th century had its historians and antiquarians, and the destruction of the curious stone – or stane – “house” was remarkably controversial even at that early date, just before the area witnessed the flow and ebb of the Jacobite army in the ’45. It is thanks to those 18th century contemporaries who took such detailed interest in the O’on during the last few decades of its existence– especially Sir Robert Sibbald, William Stukeley and Alexander Gordon – that we know as much as we do about the building. The most valuable modern summary of the subject, with conclusions as to the actual origin and purpose of the O’on, remains a paper by Kenneth Steer in The Archaeological Journal of 1960, to which the present account is heavily indebted.

Whatever that specific purpose may have been, Arthur’s O’on is now almost universally accepted – “almost” in the sense that it is accepted by all competent authorities – to have been a Roman monument, constructed during one of the three major incursions of the imperial forces, under the Flavian, Antonine or Severan regimes respectively. The building’s distinctiveness and long-established wider fame, beyond the narrow confines of antiquarianism, is indicated by the fact that it had been recognised as extraordinary for centuries, and was noted by many of the proto-historians and chroniclers of still earlier times. Fanciful theories have abounded, as might be expected, and even the more sober accounts are not altogether free from unsupported speculation.

*

The derivation of place names can be fraught with ambiguity, as with obscurity, but the origin of the name Stenhouse in this case – which is incidentally the oldest surviving “English” place name recorded in East Stirlingshire – does in fact appear to relate to the presence of the “stone house” which was Arthur’s O’on.

What might reasonably have been called stone houses had of course been highly developed in various forms by the indigenous inhabitants of Iron Age times and earlier in rough drystone form, culminating locally in the broch of Tappoch at Torwood, which might in fact be roughly contemporary with Arthur’s O’on. But a finely masoned regular structure of dressed stonework would be highly conspicuous to the later, medieval people, at a time when the vicinity would have hosted mostly varying degrees of thatched timber-and-earthwork habitations, even at the upper end of society.

The Structure of the O’on

“Not far from Carron, a round house of squair Stoones 20 ells of height, and 12 ells of Breid, it is round (as we may sie zit) haisand nae Windos but above, in manner of the Antient Tempills, quhilk are zit sene in Rome…” (Hector Boece, “Scotorum historiae a prima gentis origine”, 1527).

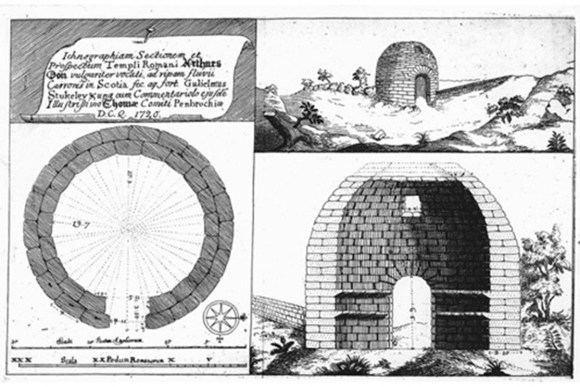

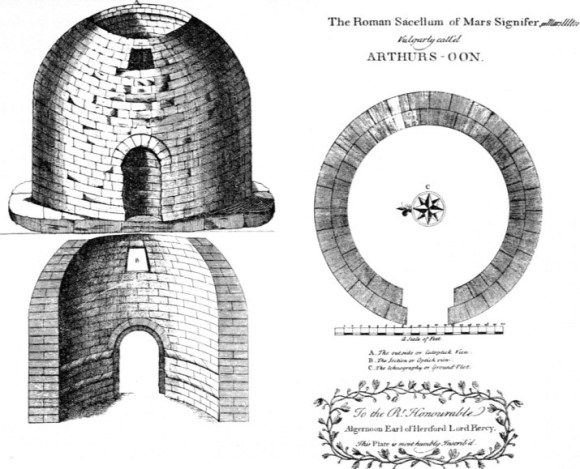

The general appearance of the building is quite beyond doubt, at least in the basic specifications of its being circular in plan, rising up in skilfully dressed freestone courses to a dome-like top, with an arched doorway facing east and, above this, a small oblong window wider at the bottom than at the top. In height it was a modest 22 feet, and a circular opening at the apex, which led some earlier commentators to compare it with the Pantheon, may or may not have been an original feature. The floor was stone-paved, and the walls were of two stones in thickness, measuring around four feet in width at the base, and narrowing towards the top. All descriptions claim that the build was of drystone, other than a very circumstantial account by an anonymous writer, rediscovered in Blair Castle as recently as 1969, which describes “very observable” cement on the interior, while also refuting the use of mortised joints between the stones. As viewed by this writer and others in the early to mid 18th century, the external surfaces of the upper half of the O’on were “very much defaced and wasted by the weather on the east and west sides”, a detail which is suggested only in Gordon’s illustration.

Gordon is alone in noting a visible foundation plinth, which he implies was hollow. This feature, of larger circumference than the O’on which it supported, was, he says, built into the hillside so that its own outward facing courses were exposed on the downhill side, and the four lower courses of the O’on itself were correspondingly concealed within the “considerable rising ground“ of the slope to the rear. Steer rejects this as an original element of the design, on the assumption that this exposure had been caused by natural erosion over the centuries, and also discounts Gordon’s “marks of three or four steps like stairs” formerly leading to the doorway, evidently only on the grounds that no other writers note these features.

The measurements taken down by the 18th century commentators agree remarkably well with one another. As Gordon stated regarding his own estimates in relation to those of Stukeley, “I confess, with Pleasure, that the Dimensions which I took of it were so very exact……that I had the good Fortune not to differ from him six inches in any of its Proportions, except about one Foot in the external diameter”.

However, despite the close basic agreement of the various drawings, descriptions and measurements made prior to its demolition, the actual profile of the building’s elevation and external appearance as depicted in these varies to a degree which will be considered in due course.

*

Nor was the interior detail consistently agreed upon. Steer refers rather dismissively to “doubtful carvings”, but all of the early descriptions do refer to traces of sculptures and inscriptions, and although the erosion of time is almost invariably noted, and the individual’s interpretation remains consequently subjective, certain identifications recur. Of these, the presumed images of an eagle, or eagles, are mentioned so consistently as to be surely beyond doubt, while the figure of Victory was recognised by some, including Sibbald in his circumstantial and entertaining account of the O’on, wherein he “viewed it narrowly with a lighted Link“. He is the only authority to have noted the specific inscription “I.A.M.P.M.P.T” high up to the south of the door. Some of the carvings and inscriptions appeared to have been deliberately erased, and of course it is far from unlikely that further “graffiti” would, conversely, be added over the long centuries; a St George’s Cross within a shield, also identified by Sibbald, was no doubt of comparatively late origin.

All descriptions agree upon two string courses or cornices encircling not the exterior but the interior walls at heights of four and six feet respectively, flat underneath and sloping “like the fore part of a desk” as Sibbald describes them, on top. Some illustrations show these cornices with flat top and sloping underside, but Sibbald is emphatic in correcting this, and Gordon’s illustration agrees with him.

The interior had supposedly at one time housed a massive stone, inevitably identified as a pagan altar, “on quhilk the Gentilis made yare Sacrifice” says Boece. Dug up in the vicinity had been some “horns of great Cows”, claimed, with equal inevitability, to substantiate the practice. This seemingly fanciful idea may nevertheless not be without foundation, if we consider the crude but vivid scene of Roman animal sacrifice – the suovetaurilia – on the Bridgeness distance slab from the Antonine Wall.

More significant was the discovery of a brass finger, polished to the semblance of gold, by Sir William Bruce in around 1700 in a crevice of the interior stonework. This artefact, since lost, was almost certainly detached from a cult statue, even more profoundly lost, which may conceivably have been placed upon the stone, a pedestal rather than an altar. Another fragment, part of a patera, an earthenware bowl, was uncovered nearby in 1699 by Edward Lhuyd, a well-known early Welsh antiquarian who corresponded with Sir John Clerk of Penicuik and like-minded contemporaries.

*

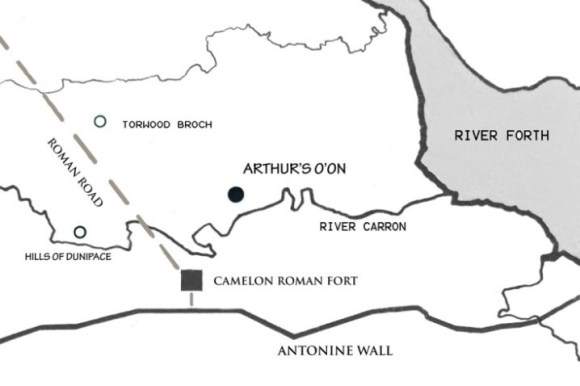

The focus of Roman activity in this area, immediately north of the Forth/Clyde frontier line established by Agricola and later utilised for the Antonine Wall, was at Camelon a few miles upstream. If any other Roman sites existed at one time at Stenhouse, they have left no trace for either historian or archaeologist, although the recent discovery of part of a small Roman altar amongst the medieval pottery kilns on the slopes below is intriguing.

Location

“Hard by this Wall of Turf, where the River Carron cuts Stirlingshire asunder, towards the left hand are to be seen two Mounts cast up, which they call Duni Pacis, and almost two miles lower an Ancient round piece of building…..” (Camden, Britannia, 1586).

Camden’s close translation, in this passage, of Buchanan’s Latin, introduces in passing the only other supposed antiquities on this northern bank of the lower Carron to have been noted by almost all other early antiquaries and historians. The Hills of Dunipace – the derivation has been liable to much popular theorising, but seems to mean simply “the mounds at the ford” – are of natural origin despite a striking appearance and a definite ambience which has survived the many modern intrusions on and around the site. Despite undoubted use by man in the past, which saw the more prominent of the pair possibly developed as a motte, and a genuine connection with Edward I of England, of whom more later, we can discard the many popular legends regarding these “Hills of Peace”, the most familiarly repeated of which claims them to be monuments cast up to commemorate a post-conflict treaty between Roman and native.

Arthur’s O’on, the authentic Roman monument under consideration here, appears to have been of somewhat less conciliatory purpose, and more consistent with the triumphalist attitude of the empire. But why did the greatest “superpower” of the age have this small but significant building constructed, at an ostensibly obscure location low down the Carron? The landscape properties of the site as it appears today have been greatly compromised, not only by the housing estates which have spread rapidly across the entire former Stenhouse policies from the west, but by others that have sprawled north from Falkirk along with related commerce, covering the flat riverside lands below. But in fact, the gently rising slopes on which both O’on and later “castle” stood represent the eastern termination, almost a promontory in its modest way, of the comparatively higher ground of East Stirlingshire as it declines towards the flattest of flat carse lands along the Forth estuary. Alexander Gordon was quite aware of this situation even in the 18th century, stating:

“If it be objected that the Situation of this Building is not upon an Eminence, those who observe the low Country of the Cars of Falkirk immediately under it, will think otherwise; for Arthur’s Oon is plainly seen from Kinneil above Borrowstoness, which is seven miles from it.”

It is perhaps significant that almost the entire eastern section of the Antonine Wall, Camden’s “Wall of Turf” would be in view.

The River Carron, quite invisible from the slopes of Stenhouse now, would in pre-improvement days have represented much more of a significant feature, its flow uncompromised by upstream weirs and dams, its course unstraightened. Tidal influence still extends as far as the present weir at Carron Works, and it is easy to imagine a coincidence of flood water and high tide leading to occasional inundations of almost delta-like aspect engulfing the landscape between here and the Carron’s confluence with the Forth, only a few miles downstream.

Any map will indicate, also, that it is not improbable that the Carron, at no very distant period, wound around what would later form the northern edges of the Carron Dams at the base of the escarpment upon which stood the O’on, and this speculation is supported if Gordon was accurate in stating that in his time the O’on stood only “200 paces” north of the river.

The promontory situation would in early times, then, be very evident. In acknowledgement of the recurrent and unproven claim that Camelon was a Roman port, one fairly recent theory, not perhaps credited officially, is that the O’on’s function was as a lighthouse guiding the vessels in to the river’s navigable course, hence the east-facing “window”. This is superficially intriguing, but is cited merely to show that speculation still persists.

*

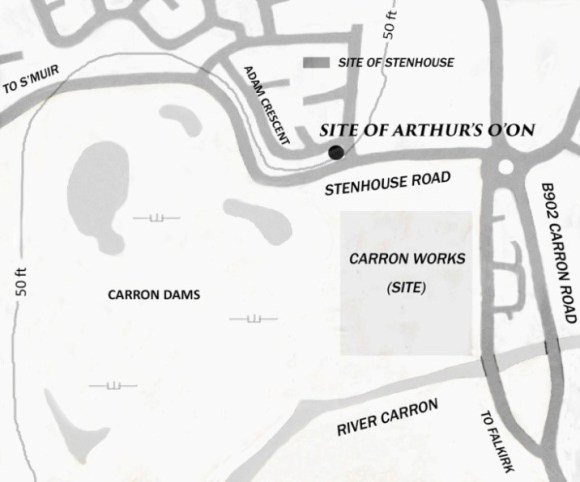

The exact site of the O’on within this setting appears to be as certain as it could be in the circumstances. Our first local historian, Nimmo, for example, was relating first-hand local information after having the site pointed out to him, only thirty years after the demolition, in the corner of an enclosure “between Stenhouse and Carron Works”, and this, corroborated by others, can be taken as conclusive. A track or pathway leading up past the site was for long known as the “O’on peth” (sic).

But the grassy, partly wooded parkland which latterly covered the site until its definitive obliteration by the 20th century housing retained not a hint of the O’on, or even apparently of Gordon’s supposed levelled-out slope. Attempts to locate any trace of stonework by excavation, firstly by Dundas of Carron Hall and others in the mid 19th century, and then by Steer and his fellow officers of the RCAHMS in 1950 uncovered nothing. However, this simply confirms Sir John Clerk’s claim that “even the very foundation stones were raised“.

While early maps are typically imprecise, the original Ordnance Survey edition of 1860 indicated, a hundred and more years after its removal, the “site of” the O’on, with the frequently mentioned adjacent cottages of Forge Row still extant at the bottom of the slope, and this was presumably the location probed by Dundas et al. The subsequent removal of Forge Row and the slight re-alignment of the Stenhouse Road, make absolute certainty impossible. However, the site has in fact been proposed overtly as the back garden of 40, Adam Crescent, and this is indicated on some later larger-scale maps. As is apparent from illus 3, a modern view affords only the vaguest impression of the former physical nature of the site.

Even allowing for modern houses, roads, landscaping and other alterations as indicated in the photograph, a more likely, indeed obvious site would seem to be around the rather higher and much more prominent edge some way further north along Castle Drive. This may however simply lend credence to the traditional identification of the lower, and seemingly much less favourable, Adam Crescent with the site, which is also perhaps supported by Gordon’s affirmation that the O’on stood “on the Declivity of a considerable rising Ground“.

Whether this riverside, edge-of-carse location, with its various advantages, had been used prior to the Romans is not known, any traces of previous occupation having been erased in turn by cultivation, by the medieval and later residences of the Bruces, and now by the present housing, but it presents a not unlikely placing for a settlement or fort of the Iron Age or earlier. There were certainly people here many centuries previously; the immediate locality has provided evidence, albeit of the dead rather than the living, in the form of Bronze Age burials and associated finds in the sandy banks of Goshen nearby (the biblical reference, not seeming immediately appropriate, arose, of course, much later).

Naturally, nothing other than its vernacular name (applied late in its history) has survived of what the O’on represented to the many generations of locals, from nobles to peasants, to whom it must have been a notable object throughout its long existence. Was it put to other uses, inhabited by families or livestock, worshipped in, resorted to as a casual shelter, or superstitiously shunned?

The Name

“….the LITTLE PANTHEON or ROMAN SACELLUM vulgarly called ARTHUR’S OON formerly situated on the NORTH BANK of the CARRON near a place named from this ancient building, STONEHOUSE…” (W. Roy, Military Antiquities, 1793).

The name itself is uncertain even as to the pronunciation of its second element; two syllables or one? Generally accepted as a vernacular contraction of “oven” (then why not “o’en”?), sometimes omitting the apostrophe, as with Roy, and sometimes, by more genteel writers, retaining the full “Arthur’s Oven”, this appears to be a straightforward reflection of the building’s oven or kiln-like shape, alternative comparisons to a doocot or a sugarloaf notwithstanding. Attempting to explain the association with Arthur, however, raises complex and never to be resolved issues.

On first consideration the name may appear to be simply a semi-facetious native nickname of the familiar sort which associates conspicuous or unusual landscape features with similarly larger-than-life characters; hence Wallace’s Putting Stone, Bruce’s Cave, Queen Mary’s Bower, Rob Roy’s Crocodile, Prince Charlie’s Well, or the numerous locations in which Auld Nick himself is supposed to toil. Other than Satan, all of these were genuine historical figures who had nevertheless achieved a semi-mythical status to a greater or lesser degree and all had authentic associations with the respective locales. Rather than discard the Arthurian attribution as random, it must be admitted that King Arthur too, if “the” Arthur is the one referred to, had supposed local associations. A persistent tradition places the scenes of Arthur’s battles not in the south-west of England or the Welsh borders, but in southern Scotland. And was not Camelon Camelot? Certainly not. The legendary Round Table, for what it’s worth, has been identified with both the King’s Knot at Stirling and, in one of the more wilfully credulous theories, with this same Arthur’s O’on; the stone of destiny and the Holy Grail itself have been relentlessly dragged in.

Whether or not there even was a Romano-British king or warlord called Arthur is still disputed, and the theories regarding him were and are extraordinarily varied, many of them far from scholarly and “not worthy the rehearsing” as Sibbald quotably said in relation to other tales. The Arthurian myth had in fact spread from whatever its actual origins were to all parts of Britain by the medieval period, and it is worthwhile in this context to quote RS Loomis who stated “Evidently the notion that any unexplained ancient structure went back to the days of Arthur was as well established in Scotland as it was in Wales or Cornwall“.

It is perhaps appropriate to note that there was in fact a historically accepted late 6thC “Artur” (a British name never common amongst royalty or the aristocracy in this country at any period) in what is now Scotland, and that he was a son of Aedan, the first Scottish king for whose activities some tenuous authentic facts may be obtained. Aedan, a key figure in later royal genealogy or pseudo-genealogy, was known in some older sources, interestingly, as “Prince of the Forth”, with a fortress at Aberfoyle, but modern historians place his principal domains farther west in Argyll. Artur himself appears to have been killed in battle, predeceasing his father, and he is in any case highly unlikely to have been associated in any way, even by later myth, with Arthur’s O’on.

*

An alternative name for the building, given commonly enough in older sources, and indicating the early recognition, by some at least, of its Roman origin, was “Julius’s Hof”, as in “howff”, still used in vernacular Scots for a shelter or temporary habitation. The credibility of this derivation is obviously fatally compromised if the Julius in question was, as claimed by some early writers, none other than Julius Caesar himself. However, while obviously discarding this attribution, Stukeley – and Gordon agreed – proposed that the nickname in fact referred to Julius Agricola, a Roman whose local credentials are indeed secure, and who is a definite contender for the builder of the O’on. This initially seems quite reasonable as far as it goes, but even had Agricola been responsible for the building, any direct link between him and the vernacular nickname should be disregarded. It is highly unlikely that the name of a Roman commander or governor, as opposed to emperor, however prestigious, would be remembered in this way in popular tradition across all the centuries that had passed since the brief Roman occupations.

The truth behind the origin of the name is instead, surely, that with the Roman association established, popular opinion simply attributed the O’on to the only ancient Roman commonly recognised by non-historians, hence the fallacious introduction of Julius Caesar to the legend.

Returning to the now generally accepted name of the building, Arthur’s O’on, it is apt to conclude by noting a suggestion made in Gordon’s account. According to this theory the whole name, Arthur, oven and all, may be a corruption of “Ard nan Suainhe”, high place of the standards, the Dark Age hero being a mere red herring. Gordon’s claim has never found favour; but given the more recent repudiation of popularly-derived etymologies for such local sites as Dunipace, Larbert and the notorious Skinflats, it is nevertheless rather tempting perhaps.

The Earliest Notices, Accounts and Theories

“…the inhabitants saiffit the same fra utter Eversioun putting the Roman Signes and subscriptiones out of the walls thereof, als they put away the Arms, and ingravit the Arms of King Arthure, commanding it to be callit Arthurs Hoisse” (Hector Boece, translation from “Scotorum historiae a prima gentis origine”, 1527)

The earliest documentary evidence relating to the building is generally supposed to be a gloss, or supplementary comment, in 13th century copies of the “Historia Brittonum” attributed, or once attributed, to Nennius, held in Cambridge, and itself dated to perhaps the 9th century. This comment is prompted by Nennius’s description of the construction of the Antonine Wall, wrongly attributed by him to the emperor Carausius. The description given, of a round house of polished stone on the bank of the Carron (“domumque rotundum politis lapidibus super ripam fluminis Carun”) allows no identification with anything other than the monument in question.

There is no reference to Arthur here, and the picture is obscured by the fact that, especially following the popularisation of the Arthur myth as accelerated by Geoffrey of Monmouth’s pseudo-history in the mid 12th century, numerous other features throughout Britain were connected with the name, including at least one other “Arthur’s Oven”, apparently in Devon. Towards the end of that century, for example, “Wonders of Britain” perhaps to be attributed to Ralph de Diceto, dean of St Paul’s in London, noted a round building called “furnus Arturi” which may seem to be our own O’on, but which is not given a geographical location. A passage in the “Liber Floridus” of Lambert of St Omer from earlier in the 12th century, is less vague in that a “palace” belonging to Arthur is stated to be located in the land of the Picts. While this may appear acceptably close geographically for a medieval non-native cleric, the reference it contains to narrative sculpture scenes implies its identity as a genuine Pictish site from north of the Forth. At least one major collection of such images – at Meigle in the heart of southern Pictland – was later intriguingly but surely coincidentally associated with Arthurian legend, specifically with Vanora or Guinevere.

But with a charter of 1293 granting the monks of Newbattle Abbey lands at “Stanhus” and citing these to be near “furnum Arthuri” we are again undoubtedly dealing with the building in question, and the Arthurian connection is shown to be established by that date. By implication the “furnum” was already expected to be recognised, by anyone able to read and utilise the charter, as a well-known landscape feature which defined its immediate area.

*

Having considered the Arthurian myth, it is as well to acknowledge again the fact that many of the earliest writers did draw the correct conclusion that the building was of Roman origin.

It is easy to be patronising about some of their further theorising regarding exactly which particular Romans were responsible and at what time. John of Fordun, in the 14th century, was one of those who proposed Julius Caesar himself as the builder, and that the O’on’s purpose was simply as a landmark proclaiming the furthermost northern extent of the Roman Empire. The latter theory is the only credible aspect of Fordun’s account, which lapses entirely into fable with his additional claims that the building was portable and was dismantled stone by stone each day and then re-erected as an overnight dwelling at each stage of the Emperor’s progress.

Julius Caesar is also, for what little it is worth, the designated Roman of choice for that other untrustworthy early historian Hector Boece.

George Buchanan’s perfectly reasonable – if now long known to be fallacious – proposal later in that century that the Emperor Severus was responsible for the construction of the Antonine Wall, and by inference Arthur’s O’on, was accepted for a very long time, largely in deference to so renowned an authority.

The quote at the start of this section relates the claim made by Boece that Edward I, Hammer of the Scots, was dissuaded from “cassin down” the monument after the local inhabitants, to placate him, erased the Roman inscriptions and replaced them with the arms of King Arthur. Stukeley relates – and rejects – another version of this in which an inscription is actually carried away at Edward’s orders, as with the Stone of Scone. The veneration of Arthur by the Plantagenet kings is accepted fact, and Edward had an undoubted association with the immediate area during the Wars of Independence, specifically with Dunipace for example, but this story is offered for what it is worth.

An early and evidently eye-witness account, seldom mentioned, is contained in a manuscript of 1569 by Henry Sinclair, Dean of Glasgow, claimed by Sibbald to be “very well Versed in our Antiquities and Ancient Writers“, who uses the “Julius’ Howf” alternative, and is worth quoting simply for his use of the vernacular of the time, as he describes the building as being “made round lyke an dowcot”, notes the apparent inscription above the door and also “ane windo four nuikit towart the eist”. Other contemporaries either visited personally or otherwise acknowledged the O’on during this period, including David Buchanan and John Urry (suggested by Lawrence Keppie to have been the “Anonymous Traveller” who has left notes on the Antonine Wall), and it features in Camden’s “Britannia” whose 1586 edition was the first of many.

But only with the advent of the early antiquarians as we know the term today is the nature and purpose of the building subjected to valuable detailed and circumstantial study.

The First Antiquarian Accounts

“Although some doubt that the round edifice near Carron Water, was a temple, yet none say that it was built by the Britains before the Romans came here, for their Temples were only Stones set in Circles, many of which may yet be seen in several places” (Sir Robert Sibbald, Historical Enquiries, 1707).

Arthur’s O’on was still extant when Mr Johnstone of Kirkland, near Dunipace, was completing his contribution, relating to Stirlingshire, to McFarlane’s Geographical Collections in 1723, but the matter-of-fact streak in him was evidently not beguiled by this structure. In the same way in which he baldly notes the names of houses and castles, he records merely “an old building in form of a sugar loaf built without lime or any other mortar so far as can be descerned commonly called Arthurs Oven”. His contribution is nevertheless valuable in that he is the first to note the brass finger of the presumed cult statue formerly housed within, thus seemingly substantiating the conclusion that the O’on was a shrine or temple.

The descriptions of other more consciously antiquarian 18th century enthusiasts, especially Sibbald and Gordon, are far more detailed and rewarding. Their accounts, in fact, are well worth reading in full, not only for their circumstantial factual content, but for the engaging and still perfectly comprehensible use of the contemporary language, and most of the more detailed specifications and descriptions in the present account derive from them.

*

Sir Robert Sibbald, Physician-in-Ordinary to Charles II, Geographer Royal for Scotland, President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, found time to devote to natural history and, more pertinently here, to antiquarianism. He was not quite local, his country seat being at Kipps near Linlithgow. Sibbald was familiar with the Antonine Wall, at least the section of it nearest him, and his account of his visit to Arthur’s O’on is very readable, with a conversational, circumstantial style, some small details briefly adding a flash of real experience as already noted.

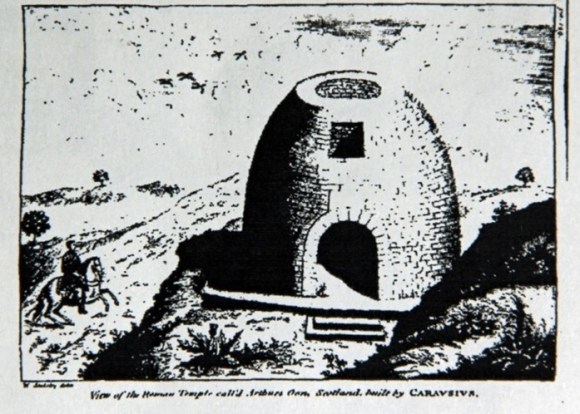

In some respects, and presumably in deference to his wider status and nationality, the principal authority for the subject was held by many to be the Englishman William Stukeley, first secretary of the Society of Antiquaries in London, and his account and drawings are well-known. In fact, Stukeley himself never ventured north of Hadrian’s Wall. Andrews (sic) Jelfe, Stukeley’s “ingenious friend“, an architect, was requested specifically, while engaged in his principal occupation of designing barracks in the north, to halt long enough in this area to record sufficient information about the O’on for Stukely’s subsequent monograph of 1720. Stukeley’s drawings – based upon Jelfe’s – and variations on it remain, along with that of Gordon, the most often reproduced in later works.

Alexander Gordon, an Aberdonian, was in some ways the characteristic Scots “lad o’ pairts”, moving from comparatively humble origins to travel widely in Europe, and to pursue numerous occupations and interests, including that of opera singer. His evident enthusiasm for all of these, including his antiquarian pursuits, was not always sustained, but we are indebted to him for his Itinerarium Septentrionale of 1726, within which his description of “the little Roman sacellum upon the River Carron” forms a vivid and highly readable chapter. It was Gordon’s musical talent which seems to have led to his acquaintance with Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, a leading antiquary of wide correspondence, whose references to Gordon in letters to those of Clerk’s own perceived status can convey a somewhat patronising tone alongside undoubted sympathy and support.

The personality revealed within Gordon’s engaging and ostensibly sensible account suggests confidence, ability, shrewdness, and perhaps an underlying conceit which shows beneath the modest deference with which he presents his various conclusions. In fact, however, Gordon’s reliability was generally denigrated by contemporaries and subsequent commentators. It is perhaps too easy for us to scorn his admission that not until almost half-way along his survey of the Antonine Wall did he realise that the rampart ran along the south side of the ditch and that the often more impressive parallel remains to the north represented in fact the upcast mound.

Rather more of concern in the present context is his claim that the doorway of the O’on faced west, when all other descriptions are unanimous in stating that it faced east, which the site alone would tend to confirm in any case.

It may or may not be worth noting one of Gordon’s principal justifications for identifying Agricola as the builder. Quoting Sibbald’s description of the letters I A M P M P T (Sibbald himself disarmingly says “these I cannot understand”) amongst the other internal inscriptions, he proposes that “it may not be reckon’d altogether absurd that they should bear this reading; Julius Agricola Magnae Pietatis Monumentum Posuit Templum”. This claim is not mentioned at all by any of the modern commentators on the O’on, and Gordon’s own plea for this theory, that “this, my Reader may either accept or reject as he pleases” will have to stand at present.

The Building’s Precise Appearance as indicated by 18th century Illustrations

“The dimensions given of this building by Gordon in his Itinerary are accurate enough, but his drawing of it is very far from being exact“ (Anonymous observer, Blair Castle documents, c 1730)

All speculation as to its exact date and purpose aside, we have at least, thanks in large part to Stukeley and Gordon, an accurate and assured knowledge of the appearance of Arthur’s O’on, despite its having been lost to sight for not far short of three centuries.

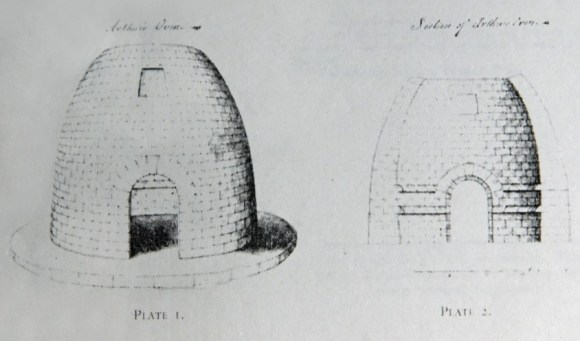

Or have we? Such was the impression until fairly recently, based largely on the respect accorded to Gordon’s drawing, supported and supplemented by Stukeley’s. This remains the standard image of the O’on, whether Gordon’s original is shown, as is usual, or one of several later illustrations based upon it. It is the sole depiction, for example, in the RCAHMS Stirlingshire volume. Moreover, the observers who noted and recorded the measurements of the building are so closely in accord with one another that the accuracy of these is surely as certain as it reasonably can be. It is in the proportions and details, and especially in the profile and the angle of the domed roof, that discrepancies arise, however.

Gordon for example, clearly states that the arching of the dome began at the upper cornice or string-course, yet his own illustration, and Stukeley’s, show the walls rising perpendicularly to some height above this. Quite apart from this, although Gordon’s drawing superficially appears as a typical example of an architect’s drawing of the early 18th century, the perspective of the roof opening is remarkably clumsy, while the doorway is naively depicted, making it appear more like an alcove.

Gordon’s was, however, by default the most credible depiction, and furthermore it accorded quite well with Stukeley’s in general appearance and proportions despite the differing techniques. The main difference is that Stukeley shows a far more elaborate surround to the doorway’s arch (technically an extrados), and also provides an unconvincingly stylised landscape setting on a flat site. The arch may be, equally with the landscape, merely a fanciful flourish, and in fact Stukeley as noted never visited the site personally.

Although Stukeley takes some pains to establish Jelfe’s reliability, going on to state that his illustration is taken “from the Draught in his Pocketbook taken upon the Spot”, it may be significant that when Stukeley returned to the subject again in relation to his later book on Carausius, the illustrations therein actually appear to have been influenced by Gordon’s drawings and description. On the face of it these later efforts by Stukeley are more convincingly realistic, and certainly more aesthetically pleasing, than any of the other older depictions. The cutaway elevation has, for scale, an amusing kilted highlander standing fully armed to one side, while the main exterior view hosts a more elegantly romantic figure on horseback to add gravitas. Yet the latter illustration shows a narrower outline than the elevation would afford, and the window is disproportionately large.

Other drawings seem worthless, at least if considered as evidence of the building’s real appearance; Sibbald’s, for example, is an extraordinarily crude near-scribble showing an attenuated structure with ragged doorway and no window. Another frequently encountered illustration, in line and water colour, appeared in Roy’s “Military Antiquities”, and this openly admits in its title to being based upon Gordon, “the perspective being however corrected”. However correct the correction actually is, the artist has exaggerated the curved outline into almost a half-sphere. A later version of this picture attempts to convey a classical aura by placing a few nymph-like female figures in the foreground, surely unconvincing representations of the characteristic local maids at any period. Another, originally featured in the second edition of Nimmo and reproduced by McLuckie is also derivative, but the artist has, like Roy, followed Gordon’s description of the protruding base set into the slope, and shows the steps. Here the O’on is backed by woodland, perhaps a reflection of the later landscape appearance, or perhaps a conventional device such as Stukeley’s. At any rate, Gordon’s and Stukeley’s original depictions retained their authority as the most definitive versions.

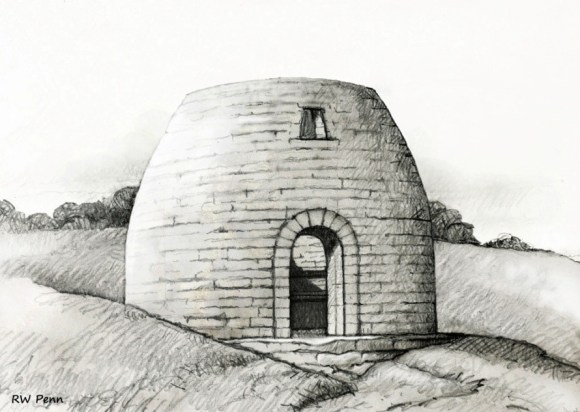

But the discoveries, or rediscoveries made in the later 20th century caused a revision of how the much-discussed building actually appeared. In 1969 an unpublished account from some time after Gordon’s description was discovered in Blair Castle.

What is especially interesting about this is that the artist was aware of Gordon’s drawing and also aware of what he regarded to be incorrect about it.

The accompanying illustration shows the wall surface already curving inwards from ground level. All other original examples have the walls rising perpendicularly, within and without, until at least the level of the upper cornice. The Blair Castle drawing also appears to show a rather enlarged window, while the overall outline appears rather too narrow in profile. However, it must be admitted that in its general appearance of artistic competence this version is far superior to those of either Stukeley or Gordon, which is admittedly no proof that it is correct in all respects.

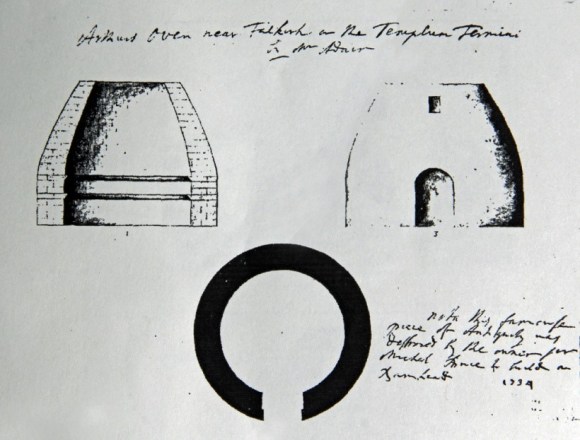

Still another “lost” set of drawings, formerly in the collection of Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, and annotated by him to identify John Adair as the draughtsman concerned, were recognised in the National Library of Scotland in the late 1980s. These might have been considered to settle the issue, given Adair’s high reputation as, in Clerk’s own words, “a very skilfull Geographer, he designed well & was no mean phylosopher“. Adair mapped the Scottish coastline and several counties including Stirlingshire; interestingly, the latter map employs a simple unadorned triangle to indicate Arthur’s O’on. Adair’s death in 1718 necessarily makes these sketches earlier than those of the other accepted authorities, and they have in fact been dated to around 1700.

Although basically resembling the familiar versions, Adair’s is somewhat inelegant in outline, the upper parts tapering up to the apex rather gracelessly inside and out, and coincidentally resembling an actual kiln or oven much more than they do, with the usual impression of a dome hardly apparent. The window, shown discrepantly as a regular rectangle, looks noticeably smaller, the opening at the apex considerably larger; in fact it is less easy to believe the top could ever have been entirely covered over if Adair’s proportions are correct. The two cornices are shown, yet again, and incorrectly, as flat-topped with sloping undersides. More noticeably, although Adair indicates courses of stonework in the section, his external elevation suggests an oddly smooth surface as though rendered in harl. Gordon does note that due to the passage of time and their own weight, the stones appear to be so closely joined that it is “almost impossible, in many Parts (my italics) to discern their Joinings”. Gordon’s own drawing, and others, rather contradict this feature, or fail to indicate it accurately, showing well-defined courses and individual blocks.

The measurements of the O’on as given by Jelfe (via Stukeley) and Gordon differ only in some details, and those only by a few inches, the most noticeable being that Stukeley makes the window a full foot higher.

The exercise of making a scale drawing based upon these measurements, and tapering the walls in from the upper cornice in as subtle a curve as the proportion allows, results in a credible outline which perhaps suggests Adair’s impression most closely, but satisfactorily amends his rather clumsy “dome” in favour of the Blair Castle version.

Despite these more recently rediscovered versions, Gordon’s admittedly striking illustration is the one that has taken hold, and is still the one most frequently used today when the subject arises, for example, in general literature about the Roman occupation of Scotland or the Antonine Wall.

The Purpose

“The common People have several Conjectures, just as their Fancies lead them, both as to the Building and Builder; for my own Part, I was once of Opinion, that it was a Temple of the God Terminus…” (George Buchanan, History of Scotland, 1582).

Buchanan goes on, following the above quote, to cite the existence in the highlands and islands, of similar but larger structures, and claims these along with the O’on as “Trophies of some famous Actions…..or Sepulchres of famous Men….”. These are obviously, as Gordon recognised, the brochs of Glen Elg and elsewhere, and wholly unconnected to this Roman structure. It is interesting that Buchanan had to venture – and from second-hand reports at that – as far as Ross-shire for these examples, when the broch at Tappoch lay only a few miles away. Even in his time, its circular open-topped form was evidently already concealed within its obscuring mound of debris, awaiting archaeology. Gordon characteristically notes that “By the faint Way, in which Buchanan gives his opinion, one may see he did not think himself very certain…”

Buchanan did, nonetheless, conclude that the O’on was a Roman structure, as of course have all subsequent authorities, but its precise purpose remains unresolved. Exact parallels cannot in fact be drawn from anywhere else, either for its design or its purpose.

*

Discounting the fanciful or otherwise notably fallacious early theories, most of which Gordon and Sibbald had already entertainingly seen off between them, a shrine, a temple dedicated to Romulus or to Terminus or to Claudius, a housing for the standards, the tomb of some distinguished Roman, or a chapel for worship, have all been suggested, and variously contended. Shrines do exist in a military context in Roman Britain, but the scale and workmanship are generally of a far inferior order. Intriguingly, Steer illustrates a carved slab from Hadrian’s Wall which, amongst the familiar panoply of winged Victory and eagle, shows a curious domed structure in the background, hardly resembling a native structure but forever inconclusive as to its actual identity. Was the O’on in fact a shrine, and if so, to whom?

There is of course the record of the cult statue, the identity of which is equally obscure, although in this case surely Victory (portrayed on distance slabs of the Antonine Wall) is a safe possibility; and more circumstantially, the repeated references to Victory and to eagles must surely be considered in any attempt at identification.

Again following Steer, then, the most sensible conclusion appears to be that the O’on was indeed a tropaeum or victory memorial or temple, an official monument constructed by legionary craftsmen and dedicated, naturally, to Victory. Which actual victory, though, was commemorated, and within which of the three principal Roman invasions? Are not a Flavian (ie Agricolan), an Antonine or even a Severan origin all equally plausible?

A Flavian attribution, from Julius Agricola’s 1st century campaigns, seems in fact to be a sound one, whether or not Agricola really played such a significant part in the first Roman invasion as Tacitus claimed in his necessarily favourable account (Agricola being his father-in-law). Such a theory would conclude that the monument was constructed following one of Agricola’s successes. Incidentally, theorists have never been able to agree upon the location of the famous Agricolan victory of Mon Graupius, which has been firmly claimed for places as far apart as Strathearn and the Moray Firth, but it seems odd that Arthur’s O’on has never apparently been drafted in to bolster the wholly inconclusive debates.

The location seems comparatively remote from security, on the “wrong” and hostile side of the frontier which had been established after the initial Roman incursion and along whose line the Antonine Wall was later constructed. However, modern historians have pointed out that the continuing Roman route north, their well-constructed road protected by a sequence of forts and other installations along its line to Perthshire, Angus and beyond, would have in effect isolated the lands to its east, including the whole of Fife. The same principle would have left the Forth-side carselands over which the O’on presided similarly “safe”, and furthermore only a few miles from the strategic location of Camelon, the departure point for imperial advances northwards, as suggested in Illus 2.

The visibility from the site of the eastern section of the Antonine Wall, within an impressively panoramic overall prospect, must also be a factor. If, as Steer and most subsequent authorities have suggested, the victory commemorated by the O’on was not Agricolan, nor yet Severan, but that of Antonine which culminated in the construction of the Antonine Wall in the 140s, then this takes us back satisfyingly to the claim made in the “Nennius” manuscripts; if, that is, we can overlook the writer’s attributing the wall to Carausias.

*

It is worth noting, perhaps, that the O’on is one of the structures or locations which has been claimed as the “Media Nemeton” named in the 8th century compilation known as the Ravenna Cosmography, the relevant section of which purportedly lists ten consecutive sites along the line of the Antonine Wall. Only one name, “Velunia” has been conclusively identified with a definite location, and that is Carriden, as confirmed from an inscription on a stone discovered there comparatively recently. The name of Media Nemeton is translated as “Middle Sanctuary” or “Middle Grove”, suggesting perhaps a ritual site, and while this seems a plausible attribution it is as much speculation as any other; Cairnpapple has also been claimed. More probably, the location, by implication around half way along the wall, could be Bar Hill or Croy Hill, although the major multi-period fort at Camelon has also been suggested. All of this must remain unsubstantiated until, perhaps, another Velunia Stone or its equivalent turns up.

Demolition

“No other motive had this Gothic knight, but to procure as many stones as he could have purchased in his own quarries for five shillings“ (Sir John Clerk of Penicuik to Roger Gale, 1743).

Arthur’s O’on was demolished, then, in 1743 by Sir Michael Bruce of Stenhouse, 6th Baronet, the proprietor of the land on which it stood, and its stones were used to build or repair the mill-dam on the River Carron closely adjacent. The story, often quoted for ironic effect, that the dam itself was swept away by a flood the day after its completion, always seemed too good to be true, and in fact the deluge responsible occurred in summer 1748. The act of constructing this dam may have been considered objectively as a beneficent and progressive, perhaps even a necessary one, and Sir Michael was by all accounts a good landlord to his tenants.

Was simple philistinism combined with parsimony the reason for his use of the stone from the building which – as he must have known – had preceded his own family seat on the site by many centuries? Is it possible that increased interest in the ancient building and consequent intrusion by sightseers played at least some part in his decision? This motive is not unknown, a later 18th century landowner in Northumberland having destroyed a Roman altar from Hadrian’s Wall for that very reason.

The culmination of the wrath of the antiquaries was a cartoon by Stukeley featuring a naked Sir Michael bearing a burden of stonework from the demolished building towards a fiery lake, goaded on in graphically painful manner by a spear-wielding demon. Until this picture (the original presumably) is destroyed, says a later, 11th Sir Michael Bruce in his Boy’s Own-style autobiography, “Tramp Royal”, the luck of the Bruces will be bad. The effect of this malediction upon the Bruces appears to have been restrained; the Sir Michael who demolished the O’on lived to be 86 and had six sons and seven daughters, while the history of the family subsequently continued placidly enough towards the end of the next century.

*

The site of the dam on the Carron for which Arthur’s O’on furnished the stones was supposed to be just downstream from the later goods railway viaduct, the remains of which can still be seen. Various claims have been made that the stones still exist, buried beneath later infill or slagheaps: surely such a valuable commodity as worked stones of this kind would simply be retrieved once the waters had subsided, and then re-used.

While excavating the site of the adjacent medieval pottery kilns in the early 1960s Doreen Hunter, formidable curator of Falkirk Museum, noted an incidental find, just south of the then still extant Stenhouse Castle, in the form of a number of detached stones which she considered unlikely to have come from Forge Row. Only three examples were specifically described, two cubes of two foot six inches, and a third more irregular. While the excavator proposed that they must surely represent remains of the O’on, the subsequent location of these stones seems to be unknown and this must remain inconclusive.

Proposals, no more than mere wishful thinking unsupported by any grant-funding or other financial backing, have variously been made to reconstruct the O’on in situ. The closest we can come to some solid notion of its appearance is at Penicuik House, where Sir John Clerk’s son had a replica constructed, perched incongruously on top of the stable block; but this was based wholly on Gordon’s drawing and may thus be unreliable.

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 2021 | The Antonine Wall in Falkirk District, Falkirk Local History Society. |

| Breeze, D.J. | 2006 | The Antonine Wall. |

| Brown, I.G. & Vasey, P.G. | 1989 | ‘Arthur’s O’on Again,’ PSAS 119 (1989) |

| Bruce, M. | 1954 | Tramp Royal. |

| Discovery & Excavation | 1962 | Council for British Archaeology |

| Fraser, J.E. | 2009 | From Caledonia to Pictland. |

| Gibson, J.C. | 1908 | Lands and Lairds of Larbert and Dunipace Parishes |

| Glennie, J.S. | 1994 | Arthurian Localities, 1869 (facsimile reprint). |

| Gordon, A. | 1726 | Itinerarium Septentrionale. |

| Hanson W.S. & Maxwell, G. | 1983 | Rome’s North West Frontier. |

| Johnstone, A. | 1723 | MacFarlane’s Geographical Collections – reprinted Love, J, Local Antiquarian Notes and Queries, 1928. |

| Keppie, L. | 2012 | The Antiquarian Rediscovery of the Antonine Wall. |

| Loomis, R.S. | 1956 | ‘Scotland and the Arthurian legend,’ PSAS 89. |

| Maxwell, G. | 1998 | A Gathering of Eagles. |

| McLagan, C. | 1873 | ‘On the Round Castles and Ancient Dwellings of the Valley of the Forth, and its tributary the Teith,’ PSAS 9 (1873) |

| McLuckie, J.R | 1870 | ‘Accounts of Arthur’s O’on,’ Falkirk Herald and Linlithgow Journal. |

| Nimmo, W. | 1777 | History of Stirlingshire. Also 1817 and 1880 editions. |

| Pryor, F. | 2004 | Britain AD. |

| R.C.A.H.M.S. | 1963 | Inventory of Stirlingshire. |

| Reid, J. | 2009 | The Place Names of Falkirk. |

| Scott, W. | 1814 | Waverley |

| Sibbald, R. | 1707 | Historical Enquiries. |

| Sibbald, R. | 1710 | The History ancient and modern of the Sherrifdoms of Linlithgow and Stirling. |

| Statistical Accounts of Scotland, Old and New | ||

| Steer, K.A. | 1960 | ‘Arthur’s O’on, a lost shrine of Roman Britain,’ Archaeological Journal, 115. |

| Steer, 1960, has full references for older authorities including “Nennius”. | ||

| Steer, K.A. | 1976 | ‘More Light on Arthur’s O’on,’ Glasgow Archaeological Journal, 4. |

| Stukeley, W. | 1720 | An Account of a Roman Temple and other Antiquities near Graham’s Dike in Scotland. |

| Stukeley, W. | 1757 | The Medallic History of Carausius. |

| Woolliscroft, D.J. & Hoffmann, B. | 2006 | Rome’s First Frontier |