The Lands of Stenhouse came into the ownership of the Bruces of Airth in 1451 and became a separate cadet branch of the family in the early seventeenth century when Sir William Bruce was in possession. He was created a Baronet in 1629. The following is a summary list of the owners with the dates upon which they succeeded. The list is approximate as the several sources available provide conflicting information.

| 1450s | Alexander Bruce |

| c1469 | Alexander Bruce to Alexander Bruce (son) |

| c1480 | Alexander Bruce to John Bruce [murdered] (son) |

| 1485 | John Bruce to Robert Bruce [killed at Flodden] (son) |

| 1513 | Robert Bruce to Robert Bruce (son) |

| c1546 | Robert Bruce to Alexander Bruce (son) |

| 1598 | Alexander Bruce to William Bruce [1st Baronet] (grandson) |

| 1630 | William Bruce to William Bruce [2nd] (son) |

| 1683 | William Bruce to William Bruce [3rd] (son) |

| c1687 | William Bruce to William Bruce [4th] (son) |

| 1721 | William Bruce to Robert Bruce [5th] (son) |

| 1732 | William Bruce to Michael Bruce [6th] (brother) |

| 1795 | Michael Bruce to William Bruce [7th] (son) |

| William Bruce to Michael Bruce [8th] (son) | |

| 1862 | Michael Bruce to William Cunningham Bruce [9th Baronet] (nephew) |

| 1888 | William Cunningham Bruce sold to John Bell Sherriff |

There was an important crossing point of the River Carron at Stenhouse and the main route north via Airth lay adjacent to the later mansion. The site of Stenhouse had probably been under continuous occupation since the Iron Age and in the Roman period a substantial circular stone temple, known locally as Arthur’s O’on, was erected on the slight eminence overlooking the river. This provided a conspicuous feature in the landscape and an obvious focal point for the local centre of power. Undoubtedly there would have been a timber hall here in the medieval period, but it was only in 1622 that a sizeable L-shaped tower house was built for William Bruce who became the first baronet seven years later. The tower house had a large stair tower at the re-entrant angle facing north (in the following plans north is at the bottom of the page) where the main entrance would have been located.

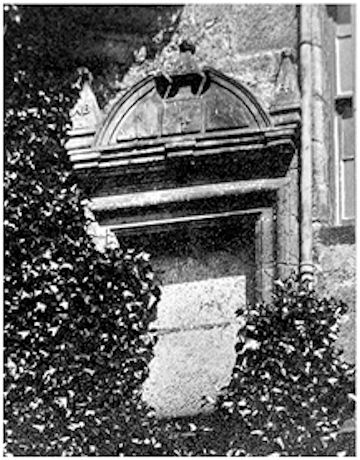

The date of erection is derived from an ornate stone which was latterly located on the south front of the main block. This is described in the RCAHMS report (1963, 239) as an old dormer window, however, though stylistically similar it is notably more elaborate than any of the other contemporary dormers and its mouldings on the cornice suggest that it surmounted a stone setting. It possessed three pyramidal finials, each carved with a mullet at the apex. The left and right finials bore the initials “WB” and “RI” respectively, for William Bruce and his second wife, Rachel Johnston. The central finial had the date “1622” in relief. The lettering is too small to have been readable on a dormer and it seems reasonable to suppose that it formed the upper section of an ornate setting above the main doorway as was common at this period. Below it would have been one or two moulded recesses for the family’s coat-of-arms (cf Torwood Castle where a shell tympanum rested over a single recess in 1566). This may also account for why when it was reset in the south wall in the 19th century it was given two new recesses.

The L-shaped tower house was four storeys tall, with an attic, and comprised a main block aligned west/east with a north wing, the former measuring 37ft 9ins by 24ft 10in and the wing 22ft 5ins wide projecting 20ft 6ins. The spacious entrance and stair tower in the re-entrant angle was 8ft 3ins in diameter. The walls were in general built of rubble 3ft 4ins thick, though the angle turrets were of ashlar masonry only 1 ft thick. The main walls were capped with an ovolo moulded eaves-course and the high-pitched gables with crow-stepping. Angle turrets occupied the top of each corner, those to the right of the entrance and on the south-west corner being rectangular. Each turret was supported in continuous corbel-courses of four members, the lower three having ovolo-and-fillet moulding and the uppermost with a cavetto moulding.

Illus: Left – reconstruction drawing of the 1622 tower house. Right – plan of third floor.

Architecturally the mansion falls into the lofty “Scottish Chateau” style described by Charles McLean and familiar to us nowadays by the surviving castles in Aberdeenshire.

Illus: Left – drawing by Fleming of the old part of Stenhouse; right – drawing by MacGibbon & Ross with the later porch on the bottom right.

The dormer pediments of the west and south elevations, as well as that to the left of the main doorway, were of a similar style to the setting over the doorway – heavily moulded broken cornices and hoods with three pyramidal finials and three simple faceted blocks of geometric pattern in the tympanum. The first floor windows were originally fitted with external wrought iron grilles for two-thirds of their heights, as was evidenced by the socket holes. Above the ground floor all of the windows had grooves showing that they had been half-glazed.

The ground floor or basement contained two vaulted rooms. The main room was the stone-flagged kitchen with an enormous fireplace against its west gable. The other room had two lockers in its walls. The first floor would have housed the hall in the main block. Both it and the room in the wing on this floor were provided with fireplaces and plenty of windows. A closet in the east wall of the hall near its north-east corner had a tiny window aperture and probably served as a gardrobe. A similar closet and ventilating window occurred on the next two floors upwards.

Sir William Bruce the first Baronet of Stenhouse died in 1630 and was succeeded by his son, also Sir William. In 1642 he married Helen Douglas, daughter of Sir William Douglas of Cavers. A heraldic panel dating to 1655 commemorates this union. It bears the initials “S/W B” and “D/H D” in raised letters over a shield parted per pale and charged; dexter, a saltire and chief, crudely cut, with a mullet at the dexter end of a blank space where the chief properly should be; sinister, a heart below three mullets. The stone was inserted into the north gable of the old block in the late 1830s during the major alterations of that period and Fleming notes that it came from over the old doorway in the stair tower. The stone need not record building work.

Internal alterations did occur from time to time and in 1698 a decorated plaster ceiling was inserted. Its original location is not known, for by the time that it was recorded by the RCAHMS it had been demolished and a small part of it re-used in the ceiling of a lobby on the first floor. Bruce-Armstrong saw it at this part of the building, between the dining and drawing rooms. In all probability it came from one of the bedrooms on the first floor. The decoration consists of a shield between the date “1698” and a label bearing the motto “DOE WELL AND DOUBT NOT.” The shield is parted per pale and charged: dexter, a saltire and chief with a mullet at the dexter end of a blank space where the chief should properly be; sinister, a fess checky between three mullets. The coat of arms is that of Sir William Bruce of Stenhouse, the fourth baronet, and his wife Margaret, daughter of John Boyd of Trochrigg.

Illus: The 1710 coat-of-arms from a building in the grounds of Stenhouse.

A third coat-of-arms was set in the east wall of the later mansion and is now in the collections of Falkirk museum. It did not, however, originate in the mansion itself. Here the evidence of Bruce Armstrong is invaluable. He states that it was taken from an old house in the park when it was demolished and intially built into the inside wall of the billiard room. It bears a shield between the date 1710 and the initials “S/ W B” and “D/ M B” (all in relief on a sunk field). The shield is parted per pale and charged: dexter, a saltire and chief; sinister, a fess checky, a mullet in dexter chief. These also belong to the fourth baronet and his wife, though in this case only one mullet is present.

The sculpture is well executed and must have come from a building of some importance. It is unlikely that that building was the stable block as Bruce Armstrong would have called it that, and in any case the stables continued in use and would have been a fit home for it had it come from there. It is tempting to think that it came from a banqueting hall of the type found at this period at Kinneil and Airth, and also suggested for Binniegreen at Balquhatstone, Slamannan.

Stenhouse sat on the eastern edge of a large open muir which remained unimproved until the late 18th century. This is clearly shown on Roy’s map of 1755. Such moorland had an economic value, particularly for grazing cattle and for the extraction of peat. In the 15th/16th century a large pottery had been established to the north of the mansion utilising the nearby peat, clay and sand. The industry was there for over a century and in that time the amount of peat consumed resulted in two large hollows – one to the east where the new recreation centre is now, and one well to the south which was utilised for the reservoirs of the Carron Company in the mid 18th century (Carron Dams).

To the south the place names of Hungry Hill and Bogside indicate that this was not prime agricultural land either. To the east were the better quality lands at Pathfoot, Stenhouse Mill and Millflatts.

The baronial mill lay on the main road from Falkirk to Stenhouse near Pathfoot. A little further north along this road and adjacent to it, on the slightly rising ground, was the old circular building which gave the area its name. The “stone house” was acknowledged to be a Roman temple, the most complete example in Britain. Yet, when in 1743 the dam for the mill required repair Sir Michael Bruce, the sixth baronet, saw it as an easy source for the stone needed and had it demolished.

The presence of the mill showed the potential that the River Carron might have for water power, if only it could be harnessed. In 1759 14 acres of the estate were feued by Sir Michael to the Carron Company for the establishment of an ironworks. The road to Stenhouse and Airth formed the northern boundary of the works site. Over the following decades Carron Company grew in importance and acquired more and more land from the Stenhouse estate. In 1760 a lade was dug from Larbert Dam to the Forge Pool at the works and reservoirs were developed to hold this water (Watters 2010). More land was required for a private canal to take goods from the foundry to Carronshore. William Cadell, junior, the managing partner acquired land to the west of the Carron Dams for his own house and built Carron Park there in 1763, and Thomas Roebuck built Mount Carron.

The Lands of Stenhouse typified the old estates in the area. Their southern boundary had been formed by the River Carron since time immemorial. The river had changed its course over the centuries, partly due to natural phenomena and partly to deliberate straightening. This meant that old meanders south of the later course were still part of the estate and their boundaries (called marches) were marked by stones. The south-west boundary was the Broomage Burn which flows through a noticeable valley. The eastern boundary was the Chapel Burn. Whilst the lower reaches of this stream cut a deep channel into the soft soils, its upper section is little more than a drainage ditch and so there it had been artificially straightened. Even less marked ditches, being little more than field drains, formed the northern limits of the estate. The Lands thus held a typical cross-section of types, with good arable near the river, intermediate pasture further up and muirland at the top.

Since 1700 the great cattle markets or trysts had been held up on Redding Muir to the south-east of Falkirk. However, the commonty used for these occasions was divided and so the fairs were moved to Rough Castle near Bonnybridge. The site did well until the 1770s when the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal made it considerably less accessible. For a while Carmuirs at Camelon was seen as an alternative site, but by 1790 the Falkirk trysts were being held on the muir at Stenhouse. Not only did this provide a sizeable income from the sales of the animals at the market, but their droppings helped enrich the poor-quality soils. Demand for temporary pasture in the immediate area rocketed and so the agricultural income of Stenhouse estate rose correspondingly.

In 1820 it was learnt that a Radical Uprising was going to take place in which an attempt would be made by the working classes to overthrow the government. The Carron Ironworks with is bountiful stores of munitions was an obvious target and it was rumoured that Stenhouse would be taken first so that the attack on the works could be led from there. Sir William Bruce therefore arranged for some locals to protect his home. These may have been part of a corps of volunteers from the works themselves as it is said that they were equipped with carronades and that Henry Stainton from the management of the Carron Company went to check up on them (Watters 2010, 129). In the event the small band of Radicals were stopped at Bonnymuir before reaching Carron.

The story goes that when Henry Stainton went to check up on the guards he made his way though woodland and shrubbery and emerged suddenly to be confronted by one of the sentries. The area between the house and Alloa road was densely planted with woodland which acted as a screen to provide privacy. It would also have obscured the works to some degree, though on a dark night the light from the blast furnaces illuminated the whole area. A little distance to the north-east of the house was a large walled garden. This was rectangular in plan with cut corners and was aligned west/east to maximise the light of the sun. As well as growing the fruit and vegetables demanded for the house it also had pleasure walks and a magnificent view to the east. To the west of the garden was a stable/office complex. About 100yds north-west of the house an ice-house was placed at the edge of the wood. It consisted of a rectangular subterranean chamber with a brick vault, entered from the south (today I’m told it is still there, covered by a modern manhole).

A large stone stood to the north of the stables and was known locally as “Ossian’s Stone”. It was considered to be an important piece of antiquity, though no one knew what it commemorated. In 1859 it was described as “a relic revered by the antiquary” and “the only object of note on the estate” (FH 29 Dec 1859). It is no longer extant. Traditions associated with the poet Ossian and the River Carron were abundant in the early Victorian period, and it is likely that this was a prehistoric standing stone.

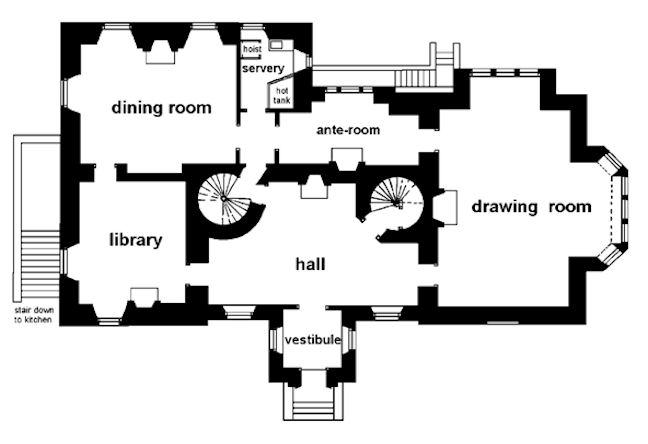

The money from the land acquisition by the Carron Company and from the Trysts had given the Bruces a good income and some of this was now spent on the house. Around 1836 the tower house was almost doubled in size using designs (now in the RCAHMS collection) by William Burn, architect. Burn kept the style of the old building and created a court at the re-entrant angle by constructing a west wing in an almost mirror image to the original building, complete with turrets and crow-stepped gables. At the same time the ground level around the mansion was raised, almost completely submerging the original ground floor and leaving just the tops of its windows exposed. From this new level a central flight of four steps led via a vestibule to a single-storey entrance hall in the courtyard. Above the main door was a coat-of-arms with a shield bearing a saltire and in the dexter chief point a shield. To either side were the supporters in high relief, dexter a chevalier in complete armour, having plumes of feathers in his helmet, and bearing in his right hand a sceptre as the crest; and sinister, a lion rampant with the crown of David II on its head, chained with an antique chain. Below the shield was a label with the family motto “DO WELL AND DOUBT NOT.” The crest was in the form of a helm above which was a cap of maintenance with a dexter arm armed from the shoulder resting on the elbow and holding a sceptre in the hand. The supporters were granted to the Bruces of Stenhouse in 1801 and are still used today. Vestibule and hall had balustraded parapets.

As a nod to modernity the west façade was given a huge ground floor bay window with a plain parapet wall. A roundel in the centre of the parapet contained another coat-of-arms and label, whilst the chamfered side of the bay depicted thistles. On the south side of the house a short flight of stairs led to a balustraded balcony and a projecting entrance flanked by windows.

Entering the 1836 house by the vestibule the visitors proceeded into the hall where they were faced with a choice of doorways. To the right was the drawing room with the large bay window just mentioned, and to the left was the library. Behind the library was the dining room. This was facilitated by a server with a hoist to the kitchen below. Proceeding through the dining room brought the visitor to a lobby with the server on the left and an ante-room ahead with the rear door and balcony. It was in this lobby that the ceiling panel of 1698 was re-used. Also from the lobby it was possible to return to the hall by way of the old staircase tower. That tower was now matched by another on the other side of the hall to maintain the symmetry and to give separate access to the upper floors of the new west wing. The upper floors had numerous bedrooms and closets.

The architect had done a good job of maintaining the character of the mansion and much of the original fabric. Not surprisingly it was often referred to as Stenhouse Castle.

Illus: East façade, c1920. Illus: West façade, c1920.

The plan by William Burn shows offices attached to the east face of the tower and the RCAHMS noted a roof raggle cut into this wall suggesting that they had been demolished by the time of their visit in 1953. These are probably the structures indicated on the 1917 Ordnance Survey map as having a conservatory on the south side. They may also be illustrated on the 1897 edition, but the surveyors or cartographers at the time made an error in placement. They were a single storey in height.

About the same time, c1839, the public road from the bridge over the River Carron to Airth was replaced by one on the present line of Alloa Road. The Bruces exchanged land with Thomas Dundas of Carronhall so that the new road could form the boundary between their properties. A tall estate wall was extended along the road to Stenhousemuir and lodge houses were erected at the south and north entrances preventing the public from using the old road.

An octagonal doocot was placed over the entrance pend to the stables and this would have been a fitting time for its construction too. It had a semicircular opening in the S side which probably contained the dove holes.

From the 1841 Census it can be seen that Sir Michael and Lady Bruce had numerous household servants, including a butler, a footman, a lady’s maid, a housekeeper, two housemaids, a laundry maid and a kitchen maid.

The last of the Bruce family to occupy the house was Sir Michael’s nephew, Sir William Cunningham Bruce, 9th Baronet, who succeeded to the estate in 1862. After moving to Stenhouse, Sir William and Lady Cunningham Bruce integrated into the local life. For example, they became patrons of the Stenhouse Curling Club in 1870. Lady Bruce died on 16 October 1873 at Stenhouse and Sir William left soon after to live in Berkshire. The mansion and garden were advertised for let, fully furnished, for up to three years in 1875. In 1877 and 1879 Sir William petitioned the Lords of Council and Session for permission to disentail his lands of Stenhouse which was preventing him from selling them. Meanwhile the property was again advertised to let:

“STIRLINGSHIRE, TO BE LET, FURNISHED, for a term of years or such period as may be agreed upon, THE MANSION-HOUSE of STENHOUSE, conveniently situated equi-distant from Edinburgh and Glasgow, and within a mile of Larbert Station. The House stands within ample grounds, having two Lodge Entrances and contains 5 Public-Rooms, 7 Family Bed-Rooms and 2 Dressing Rooms besides 9 Servants’ Rooms and other accommodation. There is a large garden with Conservatory and Vinery, and a complete Suite of Offices…”

(Glasgow Herald 5 March 1880, 4).

Permission to sell came from the Lords of Council and Session and in July 1888 Stenhouse was exposed to sale, but failed to find a buyer. A private bargain was then reached a few months later with John Bell Sherriff of Carronvale who purchased the house and estate for £40,000, thus ending over 400 years of Bruce occupation.

The large sundial at Stenhouse illustrated by Miss Sherriff in 1908 probably dates to this period and marks the new ownership. The globe at the top was carved with meridian lines and the dates and names of the zodiac.

John Bell Sherriff’s only daughter, Margaret Eugenie Flora Sherriff married William Kinross Gair, the Procurator Fiscal of Falkirk, and the couple lived in Stenhouse. She died there at the youthful age of 38 in July 1895 and a few years later WK Gair moved to Kilns House which had been built by his late father just outside Falkirk. John Bell Sherriff died just a few months after his daughter and left most of his estate to his son George. A sum of money was deposited with a trust to help to fund the post of a Jubilee Nurse at Larbert which his late daughter had helped to establish. The “High class household furniture” at the mansion-house at Stenhouse was sold.

In June 1897, the traditional time of year when new leases began, Mr Verel, shipowner, Kilwinning, moved into Stenhouse. His furniture was conveyed by rail from Kilwinning to Grahamston in 16 carriages along with his servants. He was the tenant for a number of years, after which his place seems to have been taken by Mr and Mrs Cowan Finlay. They were there until 1907 when Captain Ian and Lady Forbes of Rothiemay moved from Herbertshire Castle to take up residency. Lady Helen Forbes was a sister of the Earl of Craven and had married in 1901. His Humber car became a familiar sight in the village. The couple were socialites and the announcements of their two daughters born at Stenhouse were made in the “Clifton Society” as well as northern newspapers. They often advertised for their household staff in “The Scotsman.” In 1908, for example, a nursery governess was wanted for the first two children but had to be Roman Catholic. Later that year it was a lady’s-maid – good hairdresser, traveller and dressmaker. Of course, milk maids, laundry maids, head house-maids and a man servant were also needed.

The Forbes family did not remain long and by 1911 Mr Main of A & J Main, ironfounders, Glasgow, was in occupation. That year saw a tragic event when Andrew Frater, the 24 year old chauffeur, committed suicide in the motor garage at Stenhouse mansion. The garage was 200 yards from the house and he was discovered when a maid went to search for him after failing to find him in his bedroom. He had been ill and the doctor had just informed him that it was terminal. He left messages and presents for the other servants and his girlfriend.

Following the three-year cycle the house was available in 1913 to be sub-let, unfurnished. Gas and a telephone had been installed and it was noted that the let included 400 acres over which to shoot – clearly they were still looking for a high class of resident. It was still empty when the First World War broke out and the Larbert Voluntary Aid Detachment arranged with John Sherriff to utilise it as a wartime hospital. A sum of £169 and gifts in kind were solicited to this end. However, early in 1915 Stenhouse was requisitioned by the military as billets and so the hospital scheme had to be abandoned.

John Bell Sherriff’s grandson, Christopher Bell Sherriff, sold the house and estate to Carron Company in 1919. The house was converted into five flats for its senior employees. A new external brick wall was placed between the two stair towers on the northern façade and a stair inserted into the remaining hall to take the occupants up to the first floor. More access points were knocked into the ground floor – the central window in the bay of the west façade, for example, became a doorway with new steps up to it. Greater access was also provided to the basement.

During the Second World War the local residents were augmented by Polish officers who were billeted in Stenhouse whilst their men were stationed at Carron School. A family evacuated from Clydebank was also accommodated there.

By 1961 the building was in a poor condition and Stirling County Council issued a closing order on the Carron Company. The Company refused to spend money on the property and slowly the residents moved out and the building became emptier and emptier. In 1962 the house and the land around it were sold to Pardovan properties based in Linlithgow for development as housing; before long houses started to rise around the old mansion. Some vandalism now occurred and the new house owners, and indeed many of the older residents, asked for something to be done. Despite a small cry to save the Category B Listed building Stirling County Council was authorised to demolish it and it was razed to the ground in 1967. The site of the house is now a square area of grass amongst the 1960s housing and is owned by the Council. The cellars had been partially filled in and every now and again more collapse occurs and a void opens up in the ground.

Illus: Two stones in the collection of Falkirk Museum which probably came from Stenhouse. 0.36m square.

Sites and Monuments Records

| Stenhouse | SMR 645 | NS 8794 8291 |

| Stenhouse South Lodge | SMR 1981 | NS 8774 8287 |

| Stenhouse Ice-house | SMR 75 | NS 87 83 |

| Stenhouse Stables Doocot | SMR 54 | NS 8785 8300 |

| Stenhouse Pottery | SMR 646 | NS 8804 8314 |

| Ossian’s Stone | SMR 2191 | NS 8782 8304 |

| Arthur’s O’on | SMR 388 | NS 8795 8272 |

| Stenhouse Mill | SMR 1032 | NS 8825 8263 |

Bibliography

| Armstrong, W.B. | 1892 | The Bruces of Airth and their Cadets |

| Fleming, J. | 1902 | Ancient Castles and Mansion of Stirling Nobility. |

| Gibson, J.C. | 1908 | Lands and Lairds of Larbert and Dunipace Parishes. |

| RCAHMS | 1963 | Stirlingshire: An inventory of the ancient monuments. |

| Reid, J. | 2007 | ‘The Feudal Land Divisions of East Stirlingshire: the Lands and Baronies of Larbert.’ Calatria 24, 1-36. |

| Watters, B. | 2010 | Carron: where Iron Runs like Water. |

G.B. Bailey (2020)