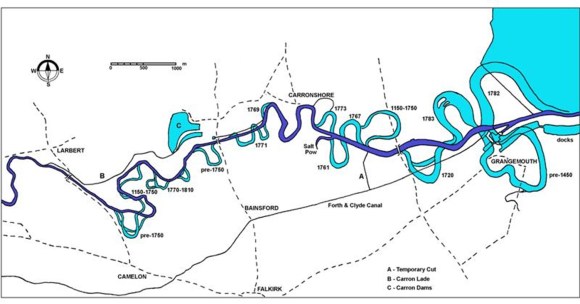

The river Carron was once a major waterway, large enough to form an effective barrier to north/south travel and prone to serious flooding in the winter. Today it is a shadow of its former self with much of the water removed in the Denny Hills for domestic use and for industry. There is reason to believe that in the Roman period it was navigable up to the fort at Camelon, though the windings made it somewhat tortuous. Even in the mid-18th century the vessels of that period were able to reach the Carron Iron Works.

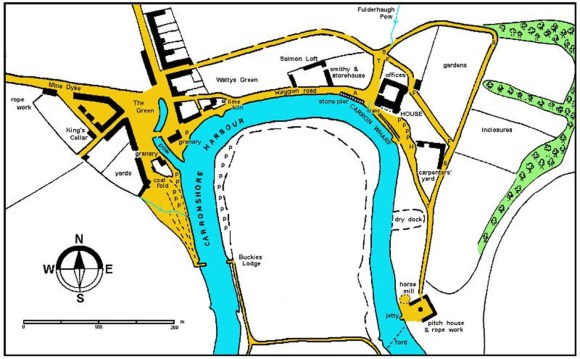

At that latter period a large meander near the mouth of the river, known as Greenbrae Reach, was used as a natural harbour, and jetties were erected to aid the loading and unloading of vessels. On the north side of this meander was the Newton Pow which was utilised by some of the smaller vessels; and its counterpart on the south side was the Grange Burn with what became known as the “Lime Wharf” in the area later occupied by the Grange School at the north end of Zetland Park. However, by sailing up the river to either the Salt Pow or another notable meander of the river at Carronshore the merchants were able to reduce the overland distance to the west coast and to Glasgow in particular. Goods, notably tobacco, coming from the west could then use these reaches of the Carron as an east coast port for onward transit to northern Europe.

Carronshore had one other advantage as a port and that was that it could be used for the sea sale of coal produced within a short distance of the north bank of the river. By 1700 the northern bank of the broad meander was known as the “Coalshor of Quarrell” (GD65) and in 1711 Robert Baird was recorded as a merchant at “Quarrellshore.” In fact, coal exports had begun in the early 17th century under the Elphinstone family, certainly before 1630. The “Longdyke” was used to take coal from the Quarrell estate to the harbour at Quarrellshore and this brought in a steady income and much needed ready cash. The harbour belonged to the Elphinstones, who also had the right to operate a ferry across the river there.

Coal was also being extracted from the Kinnaird estate to the north but its owner had to carry it across the lands of Quarrell in order to get it to the private harbour on the River Carron for export. So, on 21 September 1667, a contract was entered into between Sir Robert Elphinstone of Quarrell and Alexander Bruce of Kinnaird granting the latter full power and liberty to lead and drive his coals from his coal hills and coal haughs in Kinnaird through the lands of Quarrell and Skaithmuir to the pow and shore of Quarrell. For this privilege he had to pay the sum of four shillings Scots money for each chalder of his coal so to be transported. The roads used were known as “coal gates” and there were two of these, called the Easter and Wester Coal Gates, the former leading by the eastward of Quarrell house and the Longdyke, and the other through the township of Skaithmuir on the west. These “common coal cart roads” were opened by the proprietor of Quarrell and were his own private property. The Carronshore Pow was at the head of the Easter Coal Gate. It is probable that the Wester gate originally led to the mouth of the Mill Pow where the Chapel Burn meets the river. When Elphinstone was the owner he used to have the mud cleaned out of the pow regularly. Thereafter the mouth of this pow slowly silted up, meaning that often the ships being loaded there stuck out into the river. It was abandoned before 1757 due to the silting. Further up the river, west of Carronshore (near the later entry to the Carron Canal) there was a bank of gravel known as the “Channel Bank,” where, from the year 1710, vessels would lie to have their bottoms cleaned. West of Carronshore vessels were hauled along the river from the banks.

Quarrolleshore was one of the established Creeks for shipping and the landing of goods within the Precinct of the Port of Bo’ness. A Customs officer was based there as early as 1714 to superintend that business. Unfortunately, the Bo’ness records were lost in a fire in 1911.

“Two long miles east from the Kirk of Larbert, lyes the coalshore upon the north side of Carron, where is a ferry from Falkirk to Airth: here is a good harbour for small boats and barks yea sometimes at spring tides there comes ships here of 60 tun burden. Quarrell has a coal fold for his coals from which they are carried to the greenbrae to big ships, and by small boats and barks to Leith and the North countrey.”

(Johnston of Kirkland 1723).

The harbour was simply the bend in the river and up to twelve ships at a time tied up to polls (large mooring posts) inserted into the banks. At low tide they rested on the mud. The Quarrell Pow entered the river at Carronshore and could contain three or four vessels at a time using polls on each side. A smaller inlet just upstream and on the same side was the Mine Pow, used for loading coal.

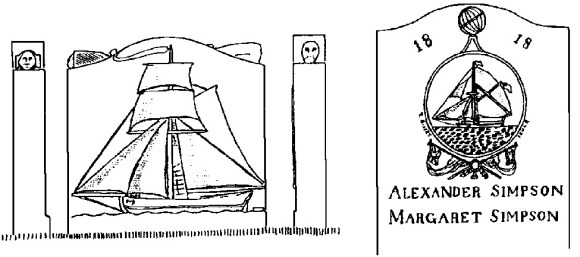

In 1725 Robert Elphinstone sold the lands of Quarrell and Skaithmuir to John Drummond, a Scottish banker. Amongst the assets were “the Shoar of Quarrell the coall fold Warehouses and heall pertinents with the ferry boat and passage and salmon fishings and other fishings within the said Water of Carron” (Reid Notes). John McLeish was appointed as the shore master in 1740 and collected 1s shore dues from each limestone vessel on behalf of Drummond of Quarrell. At that time the River was frequented up as high as Quarrolleshore by two ships belonging to James Sclanders, one of Thomas Leishman, one of Andrew Mitchell (and afterwards another built at Leith), one of Alexander Simpson, two of John Liddell, three of John Melville, one of Robert Gillespie, one of John Johnstone, one of John Sclanders, one of William Donald, and two of Andrew Ritchie – in all about 16 vessels of from 30 to 70 tons properly belonged to the place, and vessels from other ports also visited.

In the years 1739-1743 the trade at Quarrolleshore, both in exports and imports, was very considerable. In particular in the year 1742, no less than 59 vessels landed their cargoes consisting of lime, limestone, oats, peas, barley, wheat, and wheat flour, from Berwick, Prestonpans, Leith, Montrose, Arbroath, Burntisland, Dunbar, and Limekilns; and in the same year, no less than 36 vessels cleared outwards with cargoes of coal for Burntisland, Kirkcaldy, Leith, Dundee, Aberdeen, Queensferry, Montrose, and Prestonpans. After John Drummond’s death in 1742 the property passed to his nephew, George Drummond of Blairdrummond, who had no interest in the estate. He sold Quarrell to Thomas Dundas in 1749. From 1749 to 1755 John McLeish was employed by Dundas as the shore master and was given a charge-house and 8 acres. Grain vessels were now also charged 1s for each 100 bolls of grain as shore-dues. The grain trade increased substantially over that period and with marked improvements to the road from Quarrolleshore to Larbert Bridge it overtook that at the Salt Pow. Quarrolleshore vessels regularly sailed to Alnmouth and Elie for grain, with more occasional trips to Anstruther, Blyth, Cromarty, Dunbar, Dundee, Elie, Eyemouth, Largo, North Berwick and Portsoy. Thomas Dundas had a large granary built at Quarrolleshore in 1750-51 for the use of the grain merchants. In 1757 it was noted that as well as vessels taking coal from Quarrolleshore there were “Many vessels go[ing] to Quarrelshore carrying meal, grain, etc for use of the town of Glasgow and the west of Scotland”. Indeed, up until 1760 these formed over 95% of the cargoes of the ships registered at Carron. A second granary was built for Dundas in 1757. Other cargoes included peas, slates from Easdale, herrings, and wood.

Dundas employed Alexander Fiddes, merchant, as the harbour or shore master to promote the little port. Fiddes had been responsible for dock improvements at Airth and evidently realised that as that harbour there declined due to land reclamation, so that at Quarrolleshore would come to the fore. The money from the Quarrolleshore dues was mostly spent on maintaining the harbour and providing ‘gangs’ (short piers). During Drummond’s ownership the Quarrolle coalfield had been neglected. Thomas Dundas erected a fire engine in 1753 and rejuvenated the exploitation. The export of coal naturally drew the attention of the Customs officials to the site in order to ensure that taxes were duly paid.

In 1754 James Aitken appears as a tide waiter at Quarrel Shore where he was permanently stationed. There was a set-back around 1755 when a temporary halt was made on mining due to the river breaking into the underground workings.

In the years following the improvements of 1755 between 200 and 350 ships a year used Carronshore. As a result of the increased numbers it was possible to reduce the shore dues to a sliding scale, depending upon size of the vessel, to between 2d and 1s, thus encouraging more visitors. Shipmasters included Aikman, Andrew Anderson, Bald, Bell, Bishop, Calder, Carter, John Connochie, Cowan, Dalrymple, William Daniel, J Dick, Walter Duncan, Richard Gardner, Garnock, Gilchrist, Robert Gillespie, Graham, Gray, Honeyman, John Johnstone, Archibald Kemp, Kilbright, Liddell, Little, Logan, Mackay, McVey, Manwell, Mathieson, Robert Mein, James Muirhead, Murray, Neilson, William Nicol, Nithie, Robert Paterson, David Peter, James Porteous, Pottinger, Robert Primrose, Ritchie, John Sclanders, Robert Simpson, John Stark, D Stevenson, Strathearn, Alexander Stupart, Syme, Hugh Smith, Thomson, James Tibbets, Towers, Walker, Thomas Wilson, and Young. Ships registered as “Carron” appear to include both Quarrolleshore and the Salt Pow. Prior to 1745 coal from the Callendar estate was taken either to the Cobble Brae at the north end of Bainsford, or to the Salt Pow, for export.

| NAME OF SHIP | KNOWN DATES | MASTER |

|---|---|---|

| Margaret | 1745 | Ritchie |

| Seaflower | 1746-49 | Liddell; Syme |

| Friendship | 1747-97 | Sclanders; Smith; Young – ran shore 1797 |

| William | 1747-48 | Sclanders |

| Happy Janet | 1747-52 | Gillespie; Johnston |

| Thomas | 1748 | William Nicol |

| Janet | 1748-86 | Liddell; Gilchrist; Gillespie; Johnston; Mackay; Johnston; Ritchie; Stevens; Logan |

| Isabel & Euphame (Eupham) | 1749-51 | Smith |

| Henrietta (Henry) | 1750-54 | Ritchie |

| Cumberland | 1750-51 | Sclanders |

| Elizabeth | 1749-56 | Allan; Johnston; Dalrymple |

| Nicol & Colin | 1750 | Young |

| William & Charles (Charles) | 1751-54 | Sclanders |

| Michael & Paul (Michael & Polly) | 1751-59 | Mathieson; Stephens; Alexander Stupart – brig of 75 ton |

| Matty (Martha) | 1752-58 | Little; Liddell |

| Prince William (Duke William) | 1756-59 | Garnock; McVey |

| Penelope | 1758 | — |

| Charles & Mary | 1762 | |

| Betty | 1764-1784 | James Donald; Stark |

| Carron | 1767-1786 | James Porteous; Mein; Robert Paterson; Strathearn |

| Farmer | 1767 | Tuires |

| Forth | 1767 | Rea, Stevenson; Robert Mein |

| Friendship | 1767-1786 | Cowan; Kilbright |

| Gascoigne | 1767 | Built 1766 |

| Glasgow | 1767-1784 | Walter Duncan; Walker |

| James | 1767 | Carfs |

| James & Isobel | 1767 | Simpson |

| Margaret | 1767 | Bald; Thomson |

| Mary | 1767-1785 | Bishop; Balingal; Sclanders |

| Paisley | 1767-1780 | Richard Gardner; David Peter; James Tibbets; Porteous; Walter Duncan |

| Polly | 1767-96 | Archibald Kemp; Honeyman |

| Roebuck | 1767 | Aikman |

| Sophia | 1767 | Liddell |

| Stirling | 1767-1796 | Andrew Anderson; J Dick; Graham |

| Three Brothers | 1767 | Simpson |

| Woolwich | 1767 | D Stevenson |

| Argo | 1780-1784 | Niccle |

| Carron Packet | 1780-1785 | Nithie; Walker |

| Eagle | 1780 | Calder |

| Elizabeth, Anne & Maitland | 1780 | Logan |

| Glasgow Packet | 1780 | Bald |

| Grizel & Ann | 1780 | Johnstone |

| Helen & Peggy | 1780 | Murray |

| Janet & Margaret | 1780-88 | Muir; Archibald Higgins |

| John & Harry | 1780 | Cuming |

| Lady Janet | 1780 | Smith |

| Leith Packet | 1780-86 | Walker |

| Mary Ogilvy | 1780 | Bell |

| Nelly | 1780 | Saunders |

| Peggy | 1780 | Murray |

| Betsy | 1784 | Towers |

| Cecilia | 1784 | Johnston |

| Christian & Janet (Christian & Ann) | 1784-85 | Carter; Kaiter |

| Clyde | 1784-86 | Wilson |

| James | 1784 | Johnston |

| James & Mary | 1784 | Neilson |

| Lovely Mary | 1784 | Bell |

| Mary & Charlotte | 1784 | Mercer |

| May | 1784 | Thomas Wilson |

| Nancy | 1784-85 | Manuel |

| Nancy Janet | 1784 | Logan |

| Sealock Packet | 1784 | 200 tons burden for sale |

| William & Mary | 1784-85 | Logan; Sclanders |

| Betty | 1785-6 | Matson |

| Catherine & Mary | 1785-6 | Muirhead; Walker |

| Friends Increase | 1785 | Wilson |

| Janet & Mary | 1785-86 | Walker |

| Lady Eleonora (Lady Norrie) | 1785 | Wilson |

| Peggy & Betsy (Peggy & Betty) | 1785-88 | Gray; Aikman |

| Empress of all the Russias | 1786-88 | Strathearn |

| Jean Sophia | 1788 | Paterson |

| Ranger | 1788 | |

| Collier | 1788 | John Stark |

| Jamie & Jenny | 1793 | Lawrence Turnbull – sloop |

| Thames | 1793 | Pottinger |

| London | 1793 | Mackie |

1756-7 witnessed a bitter dispute between those of the maritime mercantile trade and the landowners in the neighbourhood of Quarrolleshore Harbour. Navigation had greatly increased and so the shipmasters placed additional polls in the banks on both sides of the river. The ships were fixed to these within the ordinary flood mark which was considered to be the common inland waterway. Within these tidal limits the vessels also used anchors to which the landowners objected lest they erode the banks. The main opponent was Thomas Kincaid, the tenant for the land opposite Quarrolleshore known as Abbotshaugh. He stopped the shipmasters putting in polls on that side of the river, or of using their anchors. They obtained a decree or warrant from the judge admiral instructing Kincaid not to hinder them further and this was served on 2 August 1756. Six polls were consequently fixed and used freely until July 1757 when James Goodlet-Campbell of Auchline, proprietor of Abbotshaugh, applied for a suspension of the warrant. This was not publicised and was granted. Kincaid loosed the ropes of ships tied to the polls, to their endangerment. On 25 July a vessel loaded with meal for the City of Glasgow came and tied up on one of these polls, unaware of the dispute. Kincaid loosed the ropes when the crew were ashore and it floated down river on the tide, hit the mud bank and lay on its side. Water got in through the gunholes and the cargo was badly damaged, as was the vessel. The shipmasters claimed that the suspension was irregular and unlawfully executed. Eventually it was agreed that the polls could remain if they were kept close to the brink of the river.

The small vessels – smacks, sloops and brigantines – belonged to the port, and many of them may have been constructed there. The earliest record of a ship being built at Quarrolleshore occurs in 1746 when the “Kennedy”, a sloop of 60 tons (Lloyd’s Register 1776), was commissioned for James Reddie of Dysart for trade between Leith and Norway. The fact that he was prepared to have his vessel built so far from his home port suggests that the boatyards at Quarrolleshore had already earned a good reputation by that date.

Not all the trade was in coal and grain. The customs records of 1742-1746 indicate what other types of cargo were involved. Coming from Glasgow were leaf tobacco, casks of rice, woollen products and dog skins. Goods travelling in the opposite direction, from sources around the Baltic, included barrels of linseed, undressed flax and pearl ash. From the east coast came beer, salt, whale products, glass and sail cloth. The port thus provided a transit point for material which might otherwise have to be carried around the troublesome northern coast of Scotland. In this manner it was linked into the trade routes of the entire eastern coast of Britain, including the growing port of London, as well as those of northern Europe. It was these routes that the Carron Company, from its very conception, was intended to tap.

The establishment of the Carron Company towards the end of 1759 was a momentous occasion. This company with its great ironworks was to dominate this part of the world for the next two centuries. During the construction of the works in 1760 Fiddes was consulted about the handling of heavy materials on the river, such as the hearth stones. It was Fiddes who arranged the pilots necessary for guiding the ships into the Carron from the Forth, as well as the construction of a flat (raft) for the last part of the journey. The pilot duly brought the ship to the mouth of the river Carron in March 1760, but the ship’s captain would not risk entering lest the large vessel got stranded on the mud, and so took her to Bo’ness instead. This meant extra cost for the fledgling iron company.

In 1760 Carron Company took a lease of the colliery at Quarrolle, now called Carronhall, for a period of 99 years at £600 per annum or one sixth of the coals wrought. The tack included the fire engine with all its utensils and new boiler, smith’s forge, stables, wright’s shop and shades, and other houses at the engine, the oncost men’s houses, all the colliers’ houses, the colliers, the waggon road from the pits to the harbour and from the engine, liberty of the harbour for shipping coals and the quay for laying the same there. Carron Co also had

“the priviledge of making a waggon road between their furnaces and the Harbour thro’ the grounds of Quarrol & Skaithmuir, As also a waggon road from Kinnaird Coal Pits to their furnaces and to the Harbour, with a fold there and the liberty of shipping Kinnaird Coal: no demand being made of the 4 per chalder for Kinnaird Coals passing thro’ Quarrol Coal Roads or grounds, in terms of the contract with Kinnaird: For which waggon roads & c two hundred pounds sterling yearly is demanded with forty shillings Sterling for the acre for the quantity of ground occupied by the roads & coal fold at the Harbour”.

Carron Company made extensive use of the harbour at Quarrolleshore and evidently preferred the name of “Carron Harbour.” In 1761 it was given liberty to erect a pier on the east side of the harbour (near the limekiln). On 10 November 1763 it also took a long-term tack of the harbour:

“All & eas the privilege & benefit of the private roads belonging to and the property of the said Thomas Dundas, and leading from Kinnaird coal to the leasees furnaces, and to the Harbour of Quarrole, with the liberty of shipping coal from Kinnaird coal pits free of all shore dues, and that without the leasees being subject to pay the four pence sterling per chalder for which the proprietors of Kinnaird stand bound for the use of the said roads to the proprietors of Quarrole by contract dated the 25th Sept 1667 years”…

The Company was to pay £100 per annum for a road from the blast furnaces to the Harbour, and £100 for roads from Kinnaird coal works, which it now also leased, to the harbour and furnaces. The tack of the Harbour also included the granaries and all of the houses at the Shore.

The Coal at Kinnaird was leased from James Bruce the Abyssinian Traveller. As well as transporting it to Quarrolleshore it was also taken to the harbour of Airth for export, and the prices at these places were to regulate the sales to Carron itself. It was in 1763, whilst Bruce was away on his travels, that Garbett and Gascoigne acquired the Lands of Fulderhaugh from James Goodlett Campbell of Auchline. At the time the only building at Fulderhaugh was a small cottage on the east side of the Fulderhaugh Pow. 300m to its south a pitch works was erected under the name of Samuel Garbett & Co. At the same time a dry dock was dug between the Pitch House and the cottage and Walter Duncan was brought in to build ships. Within a year they had built the Glasgow, a ketch of about 100 tons. She proved to be a reliable and fast ship. The following year the Paisley was built at the yard. After an interlude when the workforce was deployed on infrastructural projects the Stirling was launched in 1767 followed by the Forth in 1768. All four of the ships were similar, with accommodation for passengers as well as cargo and competed well with the “contract ships” of Bo’ness and Leith. A wood yard, carpenter’s yard, rope walk and a block house (for making block and tackle) helped to build further ships and to maintain those already in service.

| NAME | YEAR | DESCRIPTION | OWNER/MASTER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kennedy | 1746 | Sloop of 60 tons | James Reddie of Dysart |

| Glasgow | 1763 | Ketch of c100 tons, lengthened late 1770s to brig | Francis Garbett & Co |

| Paisley | 1764 | ditto | ditto |

| Stirling | 1767 | ditto | ditto |

| Forth | 1768 | ditto | ditto |

| Lady Jennet | 1768 | Sloop of 80 tons | T Smith & Co, Bo’ness |

| Banton | 1770s | Packet sloop for the Forth & Clyde Canal | |

| Colonel Dundas | 1780 | Brig of 100 tons | Muir & Co, Leith |

| Nelly | 1781 | Sloop of 51 tons | |

| Lerwick | 1783 | Sloop of 51 tons | Linklater, Leith |

| Margaret & Ann | 1783 | Sloop of 51 tons | Garroch & Co |

| Mary | 1783 | Sloop of 52 tons | J Sclanders, Carronshore |

| Friendship | 1783 | Sloop of 60 tons | J Galbraith |

| Margaret & Merion | 1783 | Brig of 93 tons | Hunter & Co |

| Ranger | 1784 | Brig of 136 tons | John Selby, chartered to Carron Shipping Co in 1795 |

| Commerce | 1784 | Sloop of 57 tons | H Crawford & Co, Greenock |

| Thomas | 1785 | Sloop of 58 tons | D Geddes |

| Lady Eleonora | 1785 | Sloop of 90 tons | Alexander Wilson, Carronshore |

| Carron | 1786 | Brig of 113 tons | H Smith & Co |

| Sophia | 1787 | Brig of 101 tons | J Lamb |

| Bellona | 1794 | Sloop of 69 tons | Carron Co |

| Pallas | 1794 | Sloop of 75 tons | Carron Co |

| Apollo | 1795 | Sloop of 57 tons; wrecked 1889 | Carron Co |

| Banton Packet | 1799 | Packet; converted to a coal hulk 1894 | Carron Co |

| Thetis | 1801 | Topsail school of 140 tons | Carron Co |

| Panope | 1802 | Sister ship of Thetis | Carron Co |

| Argo | 1802 | Sloop of 71 tons | Carron Co |

| Galatea | 1803 | Topsail schooner | Carron Co |

| Melampus | 1805 | Sloop of 86 tons | Carron Co |

| Latona | 1812 | Sloop of 86 tons | Carron Co |

| 1816 | Jamie & Jenny; Despatch – overhauled | Carron Co | |

| Juno | 1832 | Brigantine of 163 tons | Carron Co |

| Leith | 1861 | Wooden barge of 26 tons | Carron Co |

| Lighter No 1 | 1861 | Wooden barge of 20 tons | Carron Co |

The river traffic increased dramatically. John Smeaton, the consultant engineer for the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal, in particular, noticed the effects, having in 1763 surveyed the lower reaches of the Carron in search of a point of entry for the Canal, and having subsequently reviewed the situation four years later. The additional shipping had led to some congestion in the river and he was therefore reluctant to add to this by entering the river from the Forth and Clyde Canal at Carronshore (Smeaton 1767). In the following year, from October 1767 to October 1768, some 900 vessels are said to have plied in and out of the river, and that did not include the more numerous small craft laden with ironstone and limestone (Campbell 1961, 119). For their part the Carron Company were equally concerned that vessels waiting to enter a canal at the mouth of the Carron would hinder the progress of its ships up the river. A point put across in a series of letters:

“a very few vessels lying at anchor with goods for the canal, will at both places greatly obstruct the passage of the river, nay totally stop it for some time of the tide, and if masters of vessels should be ill-designing or ill-tempered men, they may, under the sanction of your act, with little trouble, and with tolerable pretences, entirely block up the communication between our works and the sea.”

(Scots Magazine 1 November 1768).

“…the river Carron is not, in its present situation, capable of accommodating trade, as represented by Mr Smeaton; and particularly, that the place he calls a harbour, will not admit of transhipping of cargoes passing to and from the canal, as described in his Review, p17, and 18, without great obstruction, if not wholly stopping the navigation of large vessels between the Forth and our establishments …. we are legally intitled to maintain the freedom of passage to our works from every obstruction“

(Scots Magazine 29 November 1768).

This increase in shipping seriously impeded the turn-round of vessels at the crowded harbour at Carronshore (Campbell 1961, 115). Yet, the Carron Company found it difficult to obtain sufficient vessels to carry their goods, such was the rate of increase in demand. In the autumn of 1762 they offered as much freight as any ship could take at 12s a ton, with the inducement of 10 tons of goods from Glasgow if the master so wished. As carriage from Glasgow to Carronshore was about 3d a cwt cheaper than to Bo’ness this offer would have enabled shipmasters to build up a trade between London and Glasgow. Furthermore, any ship carrying Carron goods to London was to be given preference in bringing iron for use in the works from London as ballast at the usual freight of 5s a ton.

Garbett and Gascoigne quickly realised that the shipping aspect of their business was bringing in a good profit and was capable of growing. For Garbett there was the added advantage that it facilitated the Carron Company in its work. In 1764 they therefore proposed to the Carron Company

“to erect a spacious and convenient Wharf on the banks of the Carron near their Turpentine Works, sufficient to admit ships of 100 tons burden commodiously and to give Carron Company a perpetual liberty of loading and unloading coals and their own goods there for the annual rent of 1/1 a year on condition that Carron Company will not permit any of their coals to be loaded or unloaded on the lands which are now the property of Mr Callendar.”

John Callendar owned the lands of Westerton to the east. The new wharf, known as Carron Wharf, was duly constructed adjacent to the existing cottage where the water flowing out of the pow helped to keep it clear of silt. The stone for the wharf came from the quarry adjacent to Carronhall House and was led along the coal road from Kinnaird to Carronshore. It jutted out slightly into the river, thus allowing ships using it to remain afloat for longer. A large crane or derrick was placed on the wharf to permit large items to be transferred to and from the ships.

On 3 January 1765 the Carron Company subleased the harbour at Quarrolleshore to Gascoigne on behalf of Samuel Garbett & Co, reserving certain quays, wharfs and a small portion of the adjoining ground for their own use. Gascoigne now had a monopoly of trade in this part of the river; the only exception to this monopoly being the granary on the east side of the Quarrel Pow. He raised the shore dues and promoted the use of the Carron Wharf at the expense of the Harbour which was soon bypassed by a wagon way. Gascoigne had always referred to this anchorage as Carron Harbour and now he changed the name of Quarrel Shore to Carron Shore, often abbreviated to simply Carron. He also acquired the lease of all the other houses in the small settlement there.

Gradually the shipping side of the business of Samuel Garbett & Co took up most of its attention and so in 1767, with the majority of his time occupied elsewhere, Samuel Garbett appointed his own son, Francis, to be its chairman and the company assumed the name of “Francis Garbett & Co.” Gascoigne may have seen this as an affront, but his father-in-law had already brought Gascoigne into the Carron Company as a shareholder and he was able to devote his energy to it. The need for the presence of Francis Garbett on the ground was probably the developing plans to improve the navigation of the river. They planned to make a cut across one or more loops of the meanders in order to straighten its course “to allow vessels of the burden that usually go between Bo’ness and London, to come to Fulderhaugh.” That same year, 1767, the lands of Abbotshaugh were disponed by James Goodlatt Campbell to Francis Garbett and Charles Gascoigne. Between then and 1773 the two large loops to the east of the Pitch House were duly cut with Carron Company contributing £50 towards the scheme. By this action the river moved faster along the shorter course and was therefore self-scouring. It did, however, reduce the value of the fishing rights. Flood banks were built on either side. That on the north was given a walkway so that the boats could still be tracked if required. The River Carron was classified as an inland waterway with rights of navigation. This permitted the crews of the ships to walk along the banks to pull their vessels when there was no wind or it was adverse. Tracking, as it was called, was always done by people and not by horses as that was not permitted. Often, young boys from the neighbourhood were given pocket money for this task. The old courses of the river were filled in and the land added to Abbotshaugh.

Carron Company, led by Gascoigne, lost no time in promoting the beneficial effect:

“That when we settled in this country in the year 1760, there was but little commerce passing on the river Carron, which was at that time an inconvenient navigation. That we have considerably improved the river at our own expence. That we have built large and convenient wharfs and warehouses for the accommodation of trade; and, in consequence of these improvements, there hath, for several years past, been a great resort of business. The last year there were upwards of 12,000 cargoes, amounting to 40,000 tuns, upon our own account, and about 153 cargoes, or 450 tuns, upon that of other people. That we have expended considerably above 100,000 l. Sterling upon establishments on the banks of the river, and employ many more than a thousand people in this country”

(Scots Magazine 1 November 1768).

Another reason for acquiring the Abbotshaugh estates was so that a navigable cut or canal could be made from Carronshore to the Forth and Clyde Canal near Bainsford. Planning for this reached an advanced stage before it was dropped (see the Carron Cuts at Dalderse and Abbotshaugh).

The next project of Gascoigne was to build himself a stately home nearby. This was to be Carron House (for which see Carron House) and incorporated a large warehouse and granary, a counting house, offices and so on connected with the shipping business. At the south-west corner of the existing quadrangle is a three storey warehouse known as the “Granary”. This was the generic term for such warehouses in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Such massive expenditure at so early a stage in the shipping company’s business was unwarranted and it is not surprising that the company was soon in trouble.

When James Bruce returned to his estate at Kinnaird in 1774 he found that the Carron Company had been extracting far more coal than he had anticipated and he had reason to think that he had not been getting a fair price. He believed that the Company had manipulated the markets to reduce the price. The Kinnaird coal was only exposed to sale at the Carron Wharf and the weights, kinds, and prices were entered into books kept there, to which he had no access. What he did know was that the great coal was not being handled as carefully as it ought to have been – it was “mutilated and disfigured.” It was consequently not an attractive commercial proposition as a cargo for the shipmasters; and so they and the merchants soon abandoned Carronshore and went to Alloa, Elphinstone, and other collieries, where they got coal of the usual size, qualities, and form. This meant that it was only the ships of Garbett & Co that took the Kinnaird coal form the Carron Wharf. This, Bruce claimed, was precisely what the Company wanted, for as the exportation prices were to be the rule of valuing what was sold to Carron Company, the lower these prices were the better for them. It also meant that the Company avoided the expense of carriage from the coal-hill to the harbours of Carronshore and Airth.

Carron Company also had the right to quarry stone for the building of colliers’ houses upon paying compensation. In 1776 it was noted that it had reopened Quarrolle Quarry even after it had been condemned. It had also allowed the Fulderhaugh Company to fraudulently take from thence all the stones with which they built their wharfs and magazines at Carronshore without providing the necessary compensation. During the operation of this quarry, part of the garden wall of Carronhall was undermined.

Carronshore’s overland trade with Glasgow was now on a greater scale than ever before, as is amply illustrated in the following extract of 1776:

“There is a great deal of money got here by the carriage of goods, landed at Carron wharf, to Glasgow. Such is the increase of trade in this country, that about twenty years ago not three carts could be found in the town, and at present there are above a hundred that are supported by their intercourse with Glasgow” (Pennant 1776, 240); “Carron wharf lies on the Forth, and is not only usefull to the works, but of great service even to Glasgow, as considerable quantities of goods destined for that city are landed there.” .

(Ibid, 242)

a-h road often obstructed by cannon, etc : p posts : F-F first road to brewery: S-S second road: T-T third road.

Gascoigne’s business tactics were often questionable. He tended to work to achieve a monopoly in whatever venture he was concerned. In 1757 Alexander Fiddes, merchant in Carronshore, John Whyte, merchant in Falkirk, and Alexander Brown of Quarter, had erected the granary on the east side of the Pow at Carronshore, probably on the site of the former coal fauld of Kinnaird. By agreement Thomas Dundas then took over the rights of the building and they received it back at an annual rent of £15.10s Sterling for a period of 19 years. Whyte then bought Brown’s shares in the business. They erected a landing place opposite the east end of the granary, at the foot of a stair leading to their lofts. Their main trade was in meal and grain. From September 1764 Gascoigne’s clerks seized some of Fiddes’ goods and obstructed his trade. He found it difficult to get his items back and lost some trade. Waggonways were constructed between his granary and the shipping, near to the door of the granary. Garrbett & Co also failed to keep the pier at the granary under repair. Then, in June 1765, they built a stone wall between the granary and the village, denying access to a well. The excuse was to form a coal fold in the area to the east of the granary. This was low-lying land and unsuitable for this purpose. Fiddes broke out a door through the east gable of the granary, where his pier lay. He was then accused of stealing coal in the night. In July, in the middle of the night, Gascoigne’s men built up the east door of the granary with a 2ft thick wall. Fiddes broke it down, but was threatened by Gascoigne’s masons. Another wall was placed from the SE corner of the granary to the shore; a third was put across the High Road from the harbour to the granary; and a fourth wall and a fence from the NE corner of the granary to houses near the shore so as to shut up the south doors from the Highway to the harbour. The doorway was built up again. Whilst building up the east door Alexander Fiddes sat on the foundations of their work and refused to move. They started building the top around him, but he still refused to go. Eventually Gascoigne himself came to the scene and physically removed Fiddes. It was alleged that he and two of his masons beat Fiddes up when he was on the floor. The locals heard of this beating and, worried about their own rights of access, crowded around the scene. Acting as a mob they broke down all the new constructions. Gascoigne brought a legal action, Fiddes a counter action. Eventually, a compromise was reached whereby Gascoigne agreed to buy the lease of the granary for £300.

Gascoigne did not have long to enjoy his success and his estate was sequestered. The shipping trade of Francis Garbett & Co was carried on by trustees until 1778 when the lease of the wharves in London expired and the wharf at Carron was taken possession of by creditors. The ships were then sold and run by Elphinstone (see Bowman; Somner 2000). Eventually the service was taken directly in hand by Carron Company and the Carron Shipping Company was created. One of the captains who made the transition from an independent mast to a captain of the Rebecca was Johnny Johnstone. After many years good service that vessel was laid up at Carronbank and finally towed to Carronshore for breaking up.

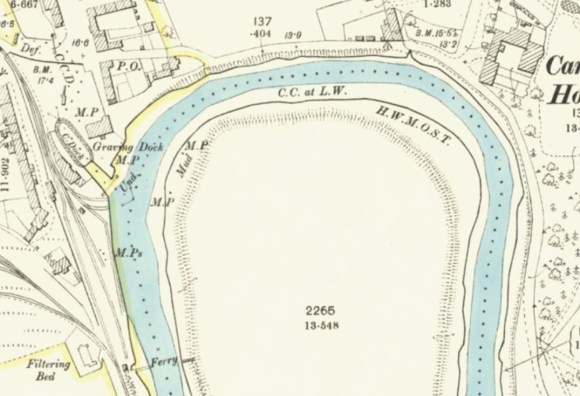

Between 1780 and 1805 some 22 ships were built at the Carronshore yard – almost one a year. This run of construction began just at the time when the old dry dock at Fulderhaugh changed hands and was closed down. The dry dock at Carronshore Pow was probably improved at this point in time by having stepped stone sides inserted. This would certainly have made it easier to do the maintenance work on the extended fleet. It would also make it the first such dry dock in the Falkirk district. It was entered through the harbour serving the 1757 granary and is shown on the 1780 plan surrounded by a large open area of road metalling which would have served as the building yard for stores and the like.

In 1782 Carron Wharf was sold by Gascoigne’s creditors and the shipping concern moved to Grangemouth. The estate was purchased by John Ogilvie, who then became “of Gairdoch.” Ogilvie bought Carron House for use as a private residence. He closed Carron Wharf and attempted to have the use of the banks for the haulage of vessels along the river stopped. At first he bore the tracking and mooring with great impatience, frequently quarrelling and disputing with the shipmasters and mariners. After a few years he began to make gradual encroachments on these rights. From time to time he erected fences across the tracking path on the north side of the river and he cut down the mooring posts. Then, at the end of 1793, he erected a high wall from the west end of Carron House into the water of the river to prevent anyone from passing that way; and, at the same time, he gave strict orders to his servants to drive away any person who might be seen tracking in the vicinity. When this failed he built a tall wall between that path and Carron House to provide privacy.

The cranes which had been used to handle the cannon were moved from Carron Wharf to the Shore west of Carronshore Pow. These guns were heavy and burdensome and required careful handling, which was not always duly given:

“We hear from Carron that on Friday last, as James Hutton and another man were hoisting a gun with a crane, the other man unfortunately slipt the handle, by which accident James Hutton received a stroke on the head from the other handle, which killed him on the spot”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 8 November 1787, 3).

It was not just the hardware that departed for military service from Carronshore. In January 1788 the newly raised 74th Regiment marched from Glasgow to Carronshore to embark for Chatham (Edinburgh Evening Courant 17 January 1788, 3).

Around 1788 Carron Company gave up its lease of the Quarrolle (now Carronhall) coal and the Dundas family took over its working. Under the lease of 1763 the family was entitled to use its own harbour – though it still had to be maintained by Carron Company.

The Channel Bank to the west of Carronshore was considerably and unintentionally augmented by an operation of the Carron Company in 1785. It broke down the reservoirs at Larbert in order to prevent their works being laid under water. The consequence of this, joined to a great spate in the river, was that the Carron made a breach in the bank at this point and so additional gravel was deposited. John Easton, tenant to Dundas of Carronhall, let sailors use the sea greens as well as the bank to grave their ships. Shipmasters generally gave him 1/- to 18d demurage for this.

The rapid development of the port at Grangemouth led to a decline in trade at Carronshore. Grain ships were now able to use the facilities at Grangemouth to transfer their cargoes to vessels using the Forth and Clyde Canal for onward transport to Glasgow. The harbour at the end of the Canal was also able to take larger vessels than those continuing down the river to Carronshore and so in 1783 the Carron Company moved its shipping operations to a new wharf on the river at Dalgrain, immediately west of the new town. It still needed to use the river so that small vessels could take its products to those at anchor at Grangemouth and to facilitate this a private canal was constructed. It commenced at a basin within the works and entered the river a little above the Chapel Burn.

As well as a range of new ships the shipbuilding yard at Carronshore was also responsible for the repair and maintenance of the Carron Shipping Company’s vessels. In 1789 Carron Company fabricated a marine steam engine designed by William Symington and so it was only natural that it should be fitted into a boat at Carronshore. This was cutting edge technology and so the boat was taken into the dry dock and the engine installed there. When she was floated out there were problems with her balance and adjustments had to be made. The empirical work carried out here eventually led to successful trials. At those trials the helmsman was David Drysdale, an employee of the dockyard and probably the son of John Dysdale who was the shipbuilder at the time.

It was to be 1801 before the experiments with steam power on water were resumed. “A letter from Falkirk dated June 24 says, ‘I had the pleasure this day of being on board a steam-boat, which was, with ease and dispatch, navigated from Carronshore to Grangemouth which in the course of the river is from 2 to 3 miles’…” (Dundee Weekly Advertiser 3 July 1801). The boat was the Charlotte Dundas. As the new engine was again made at Carron ironworks and had clearly been fitted just before this letter was written, it would seem that the fitting was also done at Carronshore.

These were the years of the press gangs. Word of their approaching Carronshore soon spread and the native sailors would make a dart to the Carron Works. They were readily given access by the warden at the gates and once inside they were safe as Joseph Stainton, the manager, had already sanctioned their refuge. Carron Company needed sailors.

During this period smuggling was rife. Unfortunately the records of the Customs Office at Bo’ness were destroyed in a fire in 1911 and so we do not have the first-hand reports of the sort available for Airth which came under the Alloa Customs House. One account of this trade was given in the Falkirk Herald on 21 November 1861:

“Carronshore at that time was like every other small port of its class; it had its smugglers, and determined ones they were. It was wholly inhabited by sailors, and not a few of them captains and owners of small sloops and schooners – daring men, who would steal across to Holland and back, run up the Forth and river in the dark, land their cargoes, and by daylight be found lying quietly either at jetty or moorings, the hands engaged in loading with manure, limestones, & c. Yet it would appear the bold smugglers did not always run clear, as the following brief narrative will show. This affair took place in Carronshore when Laurie was a young man, and his aged partner, who is still living, recollects of it well, also the names of the parties principally connected with it. But at present they will not all be given. Captain Maxwell, a native of Carronshore, was both captain and owner of a fine small schooner, which we will suppose had made some crack passages to the land of Scheldam and endless canals. Agnes or Nancy Ritchie, a niece of Captain Maxwell’s, a native and resident of the same village, had come into possession of a few hundred pounds through the death of some relative. This money was what was termed “Nance Ritchie’s fortune.” It would appear that Nance and her uncle had come to an agreement that this money should be laid out on a cargo of a certain kind of goods, which was to be shipped at some port – not in Great Britain – and to be run up and delivered at Carronshore, but not by daylight nor yet by moonlight. But, “the best laid schemes o’ mice and men gang aft agee.” However, Captain M’s smart little craft made her port and took her lading. The Captain then stood for home, reached the Forth, and, when darkness set in, boldly entered the river, nor started tack nor sheet until he had laid her alongside the old stone jetty opposite the present granary at Carronshore. The running of the cargo instantly commenced, but before that task could be wholly accomplished daylight broke on the scene, when if unfortunately happened that a certain young guidwife, whose name for the present shall be Mrs A, chanced to get out of bed, and looking out of the window, saw what was going on, and hastened to give information to the revenue officer, who instantly got up, summoned his colleagues, and made for the vessel. Resistance was useless, and flight impossible. The consequence was, the vessel was taken, with her cargo, and afterwards run down to Bo’ness, where Captain M’s schooner and Nancy Ritchie’s fortune were given the flames.

… what became of the informant. We are told she had to make her escape out of the place under the “cluds o’ nicht”.”

We learn from elsewhere from William Jack that the name of the captain was Manual and not Maxwell, and that the “guidwife” was the servant of Jenny Maxton. The Customs officer at this time was a Mr Gallinshears (Falkirk Herald 29 January 1886, 2). The same source also gives more information on the smuggling network at Carronshore.

The farm of Coldkitchen lay just to the north of Carron House and like most of the farms in the area it had a stackyard filled with stacks of hay and straw. Here, however, some of the stacks were hollow and were used to store the contraband goods. These leaders of free trade referred to the discharging of the cargo under the cover of night and its deposition in a place of safety as “calving o’ the coo.” When the cow had calved it was from Auld Westerton that the milk was dispensed and served out to the customers. Auld Westerton stood a little further to the north and consisted of a few brick-built houses on the road to Pinfoldbridge.

One of his Majesty’s Customs officials at Carronshore in 1800 was Mr Moffat, whose son Robert was badly treated by the schoolmaster there. He later related that

“I bolted and hid myself in a vessel just sailing for the east coast of Scotland. My parents having heard with what vessel I had gone, and the captain being a friend of the family, were easy. Being a good reader, I read to the captain and companions… The captain was so pleased that on our return he not only pleaded for me, but begged very hard that I might be allowed to go again as a ship boy. I went several voyages, but the sea life did not suit my tastes. I was then sent to a superior school at Falkirk…”

(Falkirk Herald 3 April 1873, 4).

Dr Robert Moffat went on to become one of Scotland’s most celebrated missionaries and the father-in-law of Dr David Livingstone.

The use of the harbour at Carronshore continued to decline and by 1845 the local minister was able to report:

“Carronshore is still employed by the Carron Company, for the landing lime and ironstone, and there is a dry dock used by the same company; a double-way iron rail-road connects it with the Carron Iron-works. The river is capable of bearing vessels of 150 tons burden as high as Carronshore, and even up to the iron-works at spring-tides; but the winding of the river makes the operation of tracking tedious and uncertain… There are several vessels belonging to Carronshore, but these all belong to the Carron Company, who have also a small dry-dock at the same place, where these vessels are repaired.”

(NSA 1845 Larbert).

Writing in 1859 the Ordnance Surveyors also noted that the Carron Company “have still a dock here for repairing their smaller vessels” (OSNB). In that year its fleet consisted of four steam ships plying regularly between Grangemouth and London; four sailing vessels on the route between Leith and Liverpool; six boats on the Forth and Clyde Canal, two of them steamers; and one steam tug at Grangemouth. Three boats of the “lighter” sort went between Carronshore and Stirlieburn for ironstone, and five between Bainsford and Calder. The main cargo discharged at Carronshore then was limestone. The old waggonway from the port to Carron ironworks seems to have remained until around 1870 in order to transport this material, after which it was replaced by a railway to serve the colliery. Carronhall Colliery Pit No 6 was quite close to the harbour and although the bulk of its coal fed the furnaces at Carron, some was exported from the pier there.

The graving dock remained in use for the maintenance of Carron Company’s lighters. Slowly the population of Carronshore changed. In 1800 it had still been dominated by mariners, but by 1860 the numbers working in the collieries had overtaken them.

The ferry across the river remained in use until well into the 20th century and for a while a ferry was provided along the river from Carronshore to Grangemouth. One of the last of the wooden boats to be built in the area was a small rowing boat with a sail capable of holding six or so passengers. It was built by James McKenzie at Langlees Farm on the south bank of the river opposite to Carronshore in 1878. On 6 April 1878 he was carrying four passengers when their drunken behaviour resulting in a dispute and he ended up shooting two of them with a pistol (Glasgow Herald 9 April 1878, 3).

The Latona seems to have been the last sea-going vessel built at Carronshore in 1812. Thereafter only lighters for the canal and the Forth came from the dockyard and it continued to maintain them until towards the end of the century. The graving dock was filled in shortly before the Second World War, though its entrance was still visible from the river until 1980. Now the only physical evidence of the old port are the remains of Carron House.

Sites and Monuments Record

| Graving Dock, Carronshore | SMR 1106 | NS 8944 8288 |

| Carronshore (Coal Shore) Harbour | SMR 1795 | NS 8958 8295 |

| Carron House | SMR 256 | NS 8974 8294 |

| Carronshore Granary | SMR 2329 | NS 8945 8288 |

| Carronshore Limekiln | SMR 80 | NS 8950 8294 |

| Carronshore Ropework | SMR 1323 | NS 8920 8300 |

| Fulderhaugh | SMR 1324 | NS 8975 8267 |

| Fulderhaugh Boatyard | SMR 1325 | NS 8974 8277 |

| Carronshore Wagonway | SMR 1818 |

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 1992 | ‘Along and Across the River Carron: a history of communications on the lower reaches of the River Carron,’ Calatria 2, 49-85. |

| Bonar, J. | 1845 | Parish of Larbert – New Statistical Account of Scotland. |

| Bowman, I.A, | 1979 | ‘The Carron Line: part 1, Carron sail 1759-1850,’ Transport History 10.2, 143-170 |

| Pennant, T. | 1776 | A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides, 1772. |

| Somner, G. | 2000 | ‘The Carron Company,’ British Shipping Fleets (ed) Fenton, R. & Clarkson, J., 162-188. |

| Watters, B. | 2010 | Carron: Where Iron Runs like Water. |