The Redding disaster was one of the worst in the history of the Scottish coalfield and a devastating event in the life of a small local mining community. At 5.00am on Tuesday 25th September 1923 an inrush of water flooded much of No. 23 pit and by the time the rescue and recovery operation was completed in December the bodies of 40 men had been recovered.

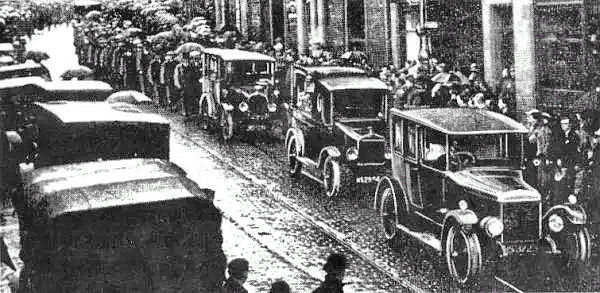

Redding No. 23 Pit Crowds at the Pit Head

Redding No. 23 Pit was operated by the Nimmo family of Westquarter House on a lease from the Duke of Hamilton. The main shaft was on the north bank of the Union Canal to the west of Redding village and the coal was being worked in a southerly direction towards a dyke of hard rock created by an ancient geological fault which separated No.23 from old abandoned coal workings. These were filled with water but it was believed that the dyke was thick enough to prevent any dangerous inrush. However it transpired that on the abandoned side of the dyke a sump, or chamber had been cut deep into the dyke making it significantly thinner at that point. This was opposite the Dublin section where coal was being stripped from the dyke. It was at this point that water entered and flooded the pit. There were 66 men trapped in the pit at the time of the disaster and a huge rescue operation was mounted involving pit rescue teams from all over the Falkirk district and beyond. After 5 hours 21 men were rescued as they emerged through a old shaft to the south east called the Gutter Hole. Huge crowds of anxious relatives gathered near the pit head and teams of divers arrived to examine the flooded workings. On 4th October five men were recovered alive and well but they were the last.

Over the next days and weeks the bodies of the other men were brought to the surface. Most had been drowned in the first inrush of water but 11 had survived for up to 14 days in a dry section of the pit which the rescuers had assumed was full of water. Several of the men had left messages for their families, at first full of optimism that rescue was near but later despairing of their own futures and those of their families. The last body was recovered from the main part of the pit in early December, the fortieth man on the fortieth day of the rescue operation. Amazingly, work began again in Pit No.23 in January.

Within days of the disaster a fund had been extablished by the Provost of Falkirk and the Falkirk Herald and within a year had raised over £60,000, well over £1 million at today’s values. A official enquiry was held in Glasgow in February 1924 and concluded among other things that it was the existence of the sump cut into the universal dyke which was the main cause of the inrush of water. They decided that the since the colliery management did not have positive proof of the thickness of the dyke they should not have allowed the stripping of coal from the dyke in the Dublin section. The enquiry also found that miners had commented in advance of the disaster on the unusual amount of water seeping into the pit but concluded that this had probably not been conveyed to the colliery managers. The enquiry made a number of recommendations for future safety in mines based on the events of September 25th 1923.

Redding No. 23 Pit was finally closed in 1958 and 22 years later a memorial stone was unveiled near Redding Cross with the names of the forty men who lost their lives. In the last two years this stone has been beautifully refurbished with mining scenes etched on a black granite stone. Much of the credit for both the original and new stones must go to Jim Anderson, former Convener of Central Regional Council and to the members of the Sir William Wallace Grand Lodge of Scotland Free Colliers whose annual demonstration on the first Saturday of August includes the laying of a wreath at the Redding Memorial.

Ian Scott (2006)

Further Information:

Amanda M. Barrie, “The Redding Pit Disaster“ Falkirk District Council (1988)