Long before Bo’ness was established as a settlement, the medieval village of Kinneil was the main centre of population. It was clustered round Kinneil House one of the most important homes of the Hamilton family. The House itself began life as a large 15/16th century fortified tower house. In the mid-16th century a ‘palace’ was built next to the tower to provide more elegant living quarters for the family which was rising to even higher prominence in the land. This building contains several murals on religious subjects thought to be amongst the finest surviving examples in Scotland. Finally, in the late 17th century, under the influence of the Duchess Anne Hamilton, two pavilions were created one of which linked the old tower to the ‘palace’. Plans to add a second ‘palace’ on the other side to create a symmetrical group were abandoned. In the late 18th century, Dr John Roebuck of Carron Company fame stayed in the house and it was he who brought the engineer James Watt to Kinneil where he worked on his improved steam engine in the little workshop at the back of the house.

Kinneil House

Behind Kinneil House on the other side of the Gill Burn is the site of the village of Kinneil which was abandoned in the late 17th century. The ruins of the 12th century church survive with only the west gable standing. The church was in use until 1669 and was destroyed by Hanoverian redcoat soldiers who stayed there during the 1745 rising. There are several flat gravestones though the markings are almost indecipherable.

The Roman fortlet of Kinneil was identified and excavated in the 1980s to the west of the house. A number of the features have been left exposed and there are information boards which show the fortlet as it would have appeared in the second century when it was built as part of the Antonine frontier.

From the late 1500s at least, ships were landing goods at the ‘ness’ which is the place where the later harbour of Bo’ness stood. During the 1600s the population grew steadily as the village of Kinneil declined in size and importance and Bo’ness soon became the major centre. The Sea Box Society dates from 1634. It involved captains putting a percentage of their earnings into a chest for disbursement to those of their number who lost ships, or for other charitable works. In the mid-18th century the town was said to be Scotland’s second most important port. The arrival of the Forth and Clyde Canal in the late 18th century and the rise of Grangemouth eventually eclipsed Bo’ness though at the end of the century the town still had 25 ships. The west pier was probably built around 1700 with the east added in 1733. This was extended in 1787. A century later in 1881 the whole port was reorganised to include a wet dock. To pay for the upkeep of the harbour the price of beer in Bo’ness was increased by two pence in 1744.

Clustered around the old west pier are several buildings with links to the town’s mercantile history. In Scotland’s Close which was once the main street of the town leading to the pier there is the ‘tobacco warehouse’ built in 1772 may have been used to store tobacco from the American colonies on its way as a re-export from Scotland to Europe. The old part of the library was once the West Pier Tavern and bears a marriage lintel with the date 1711. The nearby five-storey granary building, now converted into flats, is of slightly later date and, as the name implies, was used to store grain from the import trade. There are several other buildings of note in the vacinity like the Tolbooth, the circular Hippodrome Theatre designed by Matthew Steele in 1911, the 17th century Dymock’s Buildings recently restored, the Anchor Tavern and the Bo’ness Journal building with its ‘candle-snuffer’ roof. There are also important and interesting buildings on Corbiehall, the road that runs along what was once the water front linking Bo’ness and Kinneil. The Star Cinema was originally the Parish Church built in 1638 but much altered in later reconstructions. Behind it lies the old graveyard with many fascinating stones bearing the trade marks of sailors, and merchants. Further west one of the buildings carries a plaque indicating that it was built by the Sea Box Society.

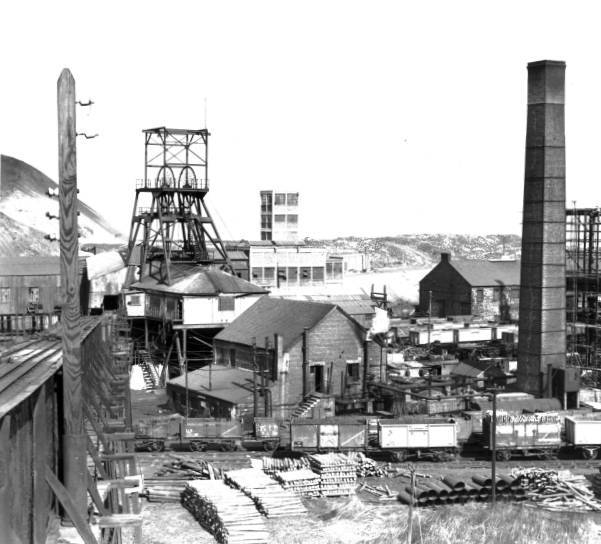

As well as shipping, the Bo’ness area, boasted a number of industries like coal mining, saltmaking, shipbuilding, pottery manufacture and iron founding. The whole of the Kinneil, Bo’ness and Carriden area is completely undermined. There were hundreds of coal shafts and coal was being removed for at least seven centuries. The great boom came with the industrial revolution in the 18th century and continued right up to the mid 20th. The black smoke from the large number of collieries gave the town a dirty and unhealthy atmosphere which only disappeared after the war. Kinneil colliery in the 1960s was thought to be the most advanced in the land but even it closed in the 1980s. Another early industry, preserved in the names Grangepans and Panbrae was saltmaking. At its height there were 16 pans employing 30 salters and for a period salt was a main source of income for the town with much of the product being exported. The last pan ceased work in 1890.

There were several shipbuilders in Bo’ness as one might expect. Two of the ships sent to Darien in the famous failed expedition in the 1690s were fitted out in the town. In the late 1700s whale fishing started but the results were mixed. At one stage there were at least seven whaling ships sailing from the harbour. In the 19th century the town became the biggest importer of pit props with vast quantities of Scandinavian timber imported for this purpose and giant stacks of props lined the foreshore from Carriden to Kinneil, so much so that the area was called by some, PITPROPOLUS!

Dr John Roebuck opened the first pottery in the late 18th century and at one time there were several potteries operating in the town. The last one closed in the 1950s and Bo’ness pottery is very collectable today. There were at one time seven foundries in the area most dating from the mid-19th century. This was part of the huge iron boom centred on Falkirk where Carron Company had established itself as the biggest foundry in the world in 1759. The last surviving Bo’ness foundry, Ballantynes, is still in operation.

The profit from these enterprises brought considerable benefit to the town with many fine houses and public buildings appearing in the 19th and 20th centuries on the terraced streets above the original settlement. The new Parish Church dates from 1888 and the handsome town hall in Glebe Park was completed in 1900. The population continued to grow throughout the 20th century and the land between Kinneil, Bo’ness and Carriden disappeared under new housing, shopping and industrial developments. The town also expanded further south covering the high land above the ‘ness’ to the east and west of the road to Linlithgow. Industrial decline brought closure to the coal mines and potteries and an end to shipping and shipbuilding, and the 1980s and 90s were a period of high unemployment and economic difficulty for the population.

However recent developments in tourism offer great opportunities for the future. At Birkhill Clay Mine, for example, visitors enter the deep caverns to see for themselves the 300 million year old fossils and learn something of the processes of mining fireclay which was an important part of the area’s industrial history. The Bo’ness and Kinneil Railway, operated by the Scottish Railway Preservation Society, houses Scotland’s large collection of historic locomotives, rolling stock and railway architecture and there are buffet facilities, a souvenir shop and picnic area. Steam trains travel the 3.5 miles to Birkhill and special charter trains can be arranged for special occasions. The Bo’ness Motor Museum has an interesting mix of classic cars and motoring memorabilia including cars and props from films and T.V.

Ian Scott (2005)

See also: Bo’ness Street Names.