Second century pottery has been found near to the Black Burn to the south-south-east of Blackness Castle and it is highly likely that there was a Roman fortlet in this vicinity overlooking the natural haven at Blackness Bay. The bay is bordered on the east by a rocky promontory or ness which protrudes from the southern shore of the Forth Estuary providing shelter from easterly winds. Whilst the jagged rocks of the ness are inhospitable to ships, the bay has a gently shelving sand and gravel beach, ideal for flat-bottomed boats to rest upon. Adair in 1712 was exaggerating when he said that it was “the best and most commodious wet dock in Britain” (GD406), but it indicates how highly thought of it was.

An early church, dedicated to St Ninian, was founded at Blackness sometime around the eighth or ninth century. Ideas, including religious ones, arrived by sea along with goods and news. The 12th century parishes of the Falkirk district concentrate along the coast – at Carriden, Kinneil, Bothkennar and Airth. That Blackness does not appear in this list is significant. It may have been that by then the population of the port and the status of its owner was less than that at Abercorn to the east or Carriden to the west, or simply that Blackness was already viewed as an outpost of Linlithgow. The Vieuxpont family held the lands of Blackness from the 12th century along with the neighbouring lands of Carriden. William de Vieuxpont granted coal from Carriden and ten shillings from all the ships and boats loaded and unloaded in his land of “Blackenis” to Holyrood Abbey. The haven was well known to the English and in 1304 it was used to land supplies to the army of Edward I then besieging Stirling.

The importance of Blackness increased with the choice of Linlithgow as a principal residence of the Scottish monarchs and for the next few centuries Blackness became involved in the power politics of the times, some of which are mentioned below. Blackness served as the port for Linlithgow and the presence of the king meant that some exotic goods were imported. A royal charter of 1389 gave Linlithgow the status of a Burgh of Regality “together with the haven of Blaknes.” A Baron Baillie was appointed to represent the coastal settlement.

The harbour was an important strategic asset, especially given its proximity to Edinburgh, and the lands of Blackness appear to have changed hands on several occasions dependent upon the politics surrounding the Scottish crown, being briefly held by the powerful Douglas family. That family had a strong presence in the area, being also connected with Abercorn and Inveravon. Enter George Crichton who succeeded his father as sheriff of Linlithgowshire in 1434. He had married a daughter of Sir William Douglas of Strathbrock, by whom he had a son called James. This seems to have brought with it a connection to Blackness and in the 1430s the lordship of Blackness was granted to him by James I. He was a dedicated servant of the king and was awarded a knighthood in 1438. After the death of James I in 1437, George Crichton and his brother, William, connived in the affairs of state to wrest control of the infant James II, making pacts with the Livingstons of Callendar and the Douglas family. These were unstable agreements and Sir George ended up burning the Douglas properties at Abercorn and several other places. In retaliation William Douglas burnt Sir George’s property at “blak nestis.” This action may have prompted the construction of a castle at the point of the ness to protect the town and haven at Blackness – the first definite mention of the castle is in 1449 (MacIvor 1982, 5); that first mention of the castle was due to the imprisonment there of Crichton’s former allies – the Livingstons (Livingston 1920, 47). It is probably not a coincidence that in 1448 George Crichton was appointed as Lord High Admiral of Scotland, nor that his brother was the Chancellor in charge of the state’s purse strings.

In June 1452 George Crichton was created Earl of Caithness. The earldom was to descend to Sir George’s assignee rather than to his natural heir and the following year Sir George nominated the King as his assignee. He then began to entail his property to prevent his son, James, from succeeding to his estates and title. James Crichton attacked and captured the castle and imprisoned his father for 9 or 10 days until the King forced him to surrender. A compromise settlement was agreed, under which James Crichton inherited the ancestral estate of Cairns and also received from the Scottish crown some land in Perthshire. The rest of Crichton’s property, as well as his earldom, were to go to the crown when he died, which he did in August 1454.

The townsfolk of Blackness were not mere onlookers to these state events as on each occasion they would have had troops billeted upon them and sometimes they were in the indirect line of fire. The settlement was on the important coastal road from South Queensferry to Bo’ness and Falkirk. In 1465 James III, then only 14 years old, granted the castle, along with the chapel of St Ninian and the surrounding land, to the Burgh of Linlithgow which was permitted to take stone and lime from the castle for the construction of a harbour. The area granted comprised the whole promontory (“montem et rupem”) of Blackness to the north of St Ninian’s Chapel extending to the high water mark on either side. The principal reasons given for this grant was the “vexations, troubles, harassments, and extortions” formerly practised by those who held the castle, upon the merchants of the burgh and others frequenting the port. The residents of the town had certainly witnessed some strange happenings. The gift, however, was recalled by an Act of 1476, revoking all grants made in the minority of James III, and especially of such places as were considered to be “keys of the Kingdom.” It is possible that a pier was made at this time, but both the castle and church survived. According to the Linlithgow Burgh records, King James IV celebrated mass at the church and made several gifts to the priests. An Instrument of Sasine in favour of the Burgh of Linlithgow in 1593 (confirmed in Acts and certification in favour of the Burgh of Linlithgow, 1660) includes the following:

“with the foresaid port of Blackness and bounds thereto belonging; with the houses, biggings, and yards in Blackness of old pertaining to the said burgh and whereof they, and their predecessors, past of all memory and in tyme byegone has been in possession, with all customes, anchorages and all other casualties, pertaining and belonging to me free ports, with all fruits, rents, lands, profites, and emoluments, whatsoever pertaining and belonging to the chaplainry called St Ninian in the said village of Blackness and right of patronage within the haill bounds, meaths, and marches of the same, whereof the said burgh has ever been in possession.“

It was not only the Scottish nobles that were vexatious to the village of Blackness for in 1481 an English fleet sailed up the Forth and set fire to it and a store ship then in the haven (Lesley 1578, 321). The castle was attacked but held out.

Before long normal service was resumed and the Scottish nobles took up arms against James III. In the course of military operations, they met his troops near Blackness, and a skirmish ensued in 1488, which terminated to the disadvantage of the king. He concluded with terms known as the “Pacification of Blackness” (Chalmer 1887, III. 354). It did not produce a lasting harmony.

James IV made a determined effort to build a fleet of his own and the story of the new dockyard that was built near to Airth to house it has been neatly told by John Reid (2002). In 1512 James IV, whilst on his latest flagship called the Great Michael during sea trials, came ashore at Blackness. At that time Blackness was home to a large band of blacksmiths and much of the ironmongery required for the fleet was fabricated there.

The Scottish fleet did not have time to see much action before it was dispersed. Hostilities with the English resumed under Mary Queen of Scots. The Earl of Arran was now Regent of Scotland and being titular head of government meant that he had control of Blackness Castle where, in 1543, he imprisoned Cardinal Beaton. Early in 1547 Edward VI came to the English throne and that September Lord Somerset marched his army into Scotland along the east coast, his troops laying waste to the countryside as they passed. The Scots were heavily defeated on the 10th at the Battle of Pinkie. The English army had been shadowed by an English fleet commanded by Lord Edward Clinton, and it arrived off Blackness on the 15th, the result was stated by William Patten in his narrative of this expedition:

“My Lord Clynton, hye Admiral of this flete, taking with him the galley (whearof one Broke is Captain) and iiii or v of our smaller vessels besides, all well appointed with municion and men, rowed up the frith a ten myle westward, to a haven town standing on the south shore called Blacknestes, whereat, towardes the water side is a castel of a pretty strength. As nye whear unto as the depth of the water thear woold suffer, the Skots, for savegard, had laied ye Mary Willoughby, and the Antony of Newcastel, ii tall ships, whiche with extreme injury they had stolen from us before tyme, whe no war between us; with these they ley thear also an oother large vessel called (by them) the Bosse and a vii mo, whear-of part laden with merchandize. My Lord Clynton, and his copenie, wt right hardy approche, after a great conflicte betwixt the castel and our vessels, by fine force, wan from them those iii ships of name, and burnt all ye residue before their faces as they ley “

(Dalziel’s Fragments of Scottish history, p.80).

Richard Broke was the captain of the Galley Subtle. The Mary Willoughby had been built for the English Navy and had been captured by the Scots in 1533, serving them well. She then had a long career back in the English Navy. Arran joined the pro-French faction, signing the Treaty of Haddington on 7 July 1548 which consented to the marriage of the Queen to the French Dauphin. That year the French used Blackness as their main ammunition depot during their support to the beleaguered Scots against the English threat.

When the Queen Mother, Mary of Guise, was made Regent the castle again came into the possession of the French, but in April 1566 it was taken from them by the Sheriff of Linlithgow. During their occupancy the Queen’s troops made an inroad upon the opposite coast, when they “spoulzeit” the towns there, and returned to Blackness with considerable booty. On two occasions during the same period an attack was made upon the castle by the Queen’s enemies within the realm and a ship of war, well furnished with artillery, was sent from Leith to “asseige” the castle. The ship was driven from the station where she had cast anchor by the violence of the weather.

Before this time, Blackness had been a busy seaport and centre of trade, intimately connected with the county town. It had a large custom-house, was the centre of a considerable population, and had two large sea-mills, sea-cruives and fisheries, coal works, and saltpans. The main exports through Blackness were heavy cargoes of coal, salt, rough woollen cloth, skins and hides. Corn, oats and wheat were sometimes exports and sometimes imports depending upon the harvest. Imports might include timber from the Baltic or Delft tiles. There was also a variety of rich items, such as wine and other alcoholic drinks. Parcels of Chinese silks were brought over from Holland, as were fine linens; tapestries and arras clothes came from Flanders. Foods included spices, pepper, nutmeg, cinnamon, mace, cloves, plums, damsons, figs, raisins, almonds and olives (Hendrie 1989, 98). “Biging and reparatioun of the schore and hewin” were in progress in 1602-4 (Records of the Convention of Royal Burghs II, 105, 204). Ships, however, were getting bigger and the lack of facilities at Blackness merely added to the political disruptions to interrupt trade there.

In June 1650 Charles II arrived in Scotland having agreed to allow religious freedom. Cromwell was compelled to invade Scotland and won a crushing victory at Dunbar in September that year. Capitalising on this he advanced to Falkirk by the end of the month and the Royalists retreated to Stirling. The English fortified Linlithgow with a garrison. Kinneil House and Haining Castle were taken over, presumably with little resistance. Blackness Castle remained in the hands of the Scots. In December the Western Army of the Scots was defeated at Hamilton, giving the English control of the country south of the Forth/Clyde isthmus. Now began a game of cat and mouse. In January 1651 a strong Scottish attack on Linlithgow failed. The main port in the area was at Blackness and the presence of a Scottish garrison there provided the Royalists with a foothold from which they could launch a counter-offensive. So on 1 April 1651 the English fleet combined with the land forces commanded by General Monck stormed it. The Scots sent a large relief force from Stirling to help, but this move had been anticipated and they were blocked by Cromwell’s troops at the River Avon.

The castle which supposedly protected the harbour and town of Blackness had over two centuries attracted the unwanted attention of various military forces and had contributed to their decline. What really led to its demise, however, was the rise of an energetic new port nearby at Bo’ness which had the backing of a powerful patron in the shape of the Dukes of Hamilton. Not unnaturally, the Royal Burgh of Linlithgow made numerous attempts to prevent the seaport of Bo’ness from developing. On 29 September 1601, for instance, the Provost, Bailies, Council, and Community of Linlithgow sent a complaint to the Privy Council against the granting of burgh status to the town of Bo’ness. They pleaded that the grant was to the “grite wrak and decay of thair burgh and heaven [Blackness] quhilk is biggit and repairit be thame for saiftie of schipis and boittis upoun thair grit expensses.” It was to no avail.

The denuded nature of the settlement at Blackness is reflected in an incident that occurred in 1636. A ship with grain from Rotterdam arrived at Bo’ness, but the Harbour Commissioners there refused to allow the grain to be unloaded for fear of spreading the plague. The grain had been on board for some time and was heating, and would soon spoil. As the ship was free from sickness, the Privy Council was petitioned for permission to land it. The Lords granted permission for the ship’s company, and such workmen as the magistrates of Linlithgow thought fit, to discharge the cargo and store the grain in some lofts and other convenient places at Blackness or Carriden to preserve it from spoiling. The ship’s company and workmen were to remain apart by themselves with the grain till such time as the magistrates prescribed their trial. Blackness was evidently considered remote.

The glory days of the port were over and decline set in. Tucker, reporting for Cromwell in 1656 was harsh in his assessment:

“Blacknesse, Cuffe-abowt, and Grange, the former of them sometimes reported to have beene a towne, and at that time the port of Lythquo, but now nothing more than three or foure pitifull houses, and a peice of an old castle.”

(Tucker Report 1824)

Writing in 1710 Robert Sibbald was referring to the past when he said

“There were, many rich men masters of ships lying there; and the cities of Glasgow, Stirling, and Linlithgow, had a great trade from thence with Holland, Bremen, Hamburgh, Queensburgh, and Dantzick, and furnished all the West country with goods they imported from these places, and were loaded outwards with the products of our own country”

(Sibbald 1710, 17).

Just two years later Adair, whilst admitting that the anchorage at Blackness was admirable, had intended to place the associated infrastructure for the British fleet, such as store houses, at Bo’ness where the tradesmen now resided.

There seems to have been a concerted effort at the end of the 17th century by the Town Council of Linlithgow and the Guildry there to revive the fortunes of the port. As a result of intense lobbying they got the Custom House transferred back from Bo’ness to Blackness in 1679 “there to remain in all time thereafter” (sic). To achieve this they evidently agreed to construct buildings at the harbour to facilitate the trade and also the operations of the Customs. The narrow strip of coast to the west of the pier was known as the Green, and belonged to Linlithgow Burgh Council. Here they decided to construct a substantial four-storey granary/warehouse with living accommodation. As this was a joint project, the eastern half of the site for the warehouse was feued to the Guildry of Linlithgow in 1679 and when completed that Guildry owned half of the building. The warehouse was 100ft long by 22ft 6ins broad internally (107ft by 28ft externally) and had three storeys and a garret. The ground floor consisted of cellars and stables, and a baker’s oven stood in a lean-to. A broad stairway on the south side led to the first floor which was also used for storage and gave access to the living rooms in the upper floors. Pig sties and middensteads were located in the grounds for the tenants. Offices were provided for the Customs officials in the western part of the building.

Over time the whole building became known as “the Guildry.” It had cost, in total, £6,993 6s 8d. A weigh-house and pack-house stood between the warehouse and the pier. The Guildry building now formed the northern side of an open public square.

The other side of this square was occupied by an old building which was also owned by the town of Linlithgow. As well as storage it contained the village inn where ships’ crews could drink or spend the night. It was in a derelict condition and so shortly thereafter it was rebuilt using a loan from the Linlithgow Guildry. The new building was three stories high and measured 50ft in length, by 18.5ft in breadth within the walls.

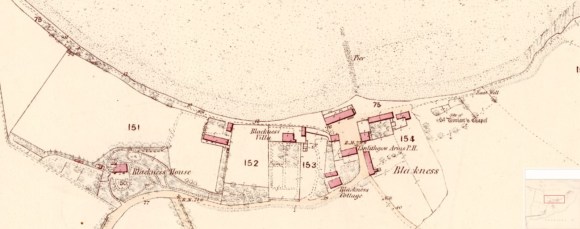

Roy’s map of 1755 shows the small town of Blackness spread out along the coastal road. The pier can just be made out with the two granaries to its south. Eastward the buildings all lie on the south side of the main road, but westward they occupy both sides and are more densely packed. It was in this westward area that the private warehouses stood in the grounds of the shipmasters’ houses.

The granaries and harbour at Blackness were used by the Burgh Mills up until 1785. The two public granaries were put up for rent from time to time:

“A desireable situation for carrying on business in the corn trade, malting, soap boiling, or other manufactures. To be let for such a term of years as can be agreed upon, and entered to at Whitsunday next. These large buildings belonging to the town and guildry of Linlithgow, situated at the port and harbour of Blackness, two miles east from Borrowstounness, and about the same distance from Linlithgow.

These houses are large and commodious, and at a small expence, may be adapted for carrying on extensive business in different branches; the one being 107 feet in length, by 23 feet in breadth within the walls, three stories high, with garrets; the other 50 feet in length, by 18.5 feet in breadth within the walls, and three stories high.

Their vicinity to the towns of Linlithgow and Borrowstounness, and to coal and lime, as well as the conveniency of shipping grain or other goods, render them an advantageous situation.

Any person or company which these subjects may suit, may apply to Provost James Andrew, Linlithgow.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 11 January 1787,1c).

The advertisement for 1796 hints at the slowness of the trade at Blackness, after describing the Guildry it goes on to say that it:

“may, at no great expence, be fitted up for carrying on an extensive trade, either in the herring fishing or import and export of grain. The pier may also be repaired at a moderate expence, and by this means much ship business conveniently carried on, the anchoring ground without being good, and the beach within the bay to the eastward of the pier extensive, and safe for shipping or landing goods, as carts can go alongside vessels when the tide has left them. The harbour is the property of the town of Linlithgow, to which also belongs ground adjoining both to the warehouse and pier.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 18 February 1796, 1d).

It is not surprising that the larger vessels then in use preferred the shelter of the deeper water just along the coast at Bo’ness. By this time a large brickworks had been established to the south of the village to exploit the fine laminated clays there. Its chief products were house bricks and drain tiles which could be shipped from the pier to ports along the Forth. Its chief market was the New Town of Edinburgh

As well as the brick work, Forrest’s map of 1818 shows an alum mine and a Roman Cement Work at Bridgeness, the latter owned by a Mr Taylor. This was a chemical works which had been established around 1813 and later went on to make black ash from bleacher’s refuse. This substance was used in the Leblanc process to produce sodium carbonate which was needed for the manufacture of soap and glass. The process used at the works released hydrogen chloride into the atmosphere, causing severe damage to vegetation over a wider area. Not surprisingly therefore, in 1827 a court case was brought against Taylor by the owner of Blackness Villa which lay immediately to the east. One of those that gave evidence was Spence Wood who had been sea-bathing at Blackness the year before. This leisure activity had replaced shipping in the limited economy of the village. 50yds further east was the house of Mr Jeffrey who had resided there all of his life. In the summer months he let part of his house to families who went there for the sea-bathing and at that time was accommodating eight families at a time. Unfortunately, in July 1828 one of the bathers, Mr Rankine, a law-student, the son of a bookseller at Falkirk, was drowned. It was such middle-class professionals from central Scotland who were vacationing at Blackness. It never reached the mass popularity of seaside resorts such as Portobello because of the difficulty of access. It was never provided with a railway link. The Linlithgow Guildry placed a large wooden bathing-house in front of the Green, and installed garden seats on the Green itself, to promote leisure activities.

A poem of 1833 tells us that the wooden bathing shed had been replaced by one of stone by that date. It also says that the granary had been renovated and that the pier was “a shapeless heap of stones.” As late as 1868 Robert Gillespie noted the importance of the “revenue derived from family lodgers, who, during the summer season, resort to this popular part of the Frith for the sake of sea-bathing.” However, he goes on the say “even this uncertain, and, at best brief benefit to the village, is rapidly going elsewhere” due to “Steam, that greatest magician of our time” which was taking people to Dunoon and beyond

(Gillespie 1868, 199).

Clearly the port of Blackness was doomed to failure and obscurity. In 1856 the Ordnance Surveyors described the settlement:

“A small village at the east end of the parish of Carriden composed of a few scattered cottages which are for the most well built and are generally occupied by agricultural labourers. There is a small pier or landing place which seems to have been rudely put together. There is neither sloop nor boat belonging to the place. It is the port for the Town of Linlithgow and is the property of that burgh.”

The pier shown on the accompanying plan is not given a firm outline indicating that it was little more than a rickle dyke and in ruins. Its length was in the region of 250ft. It fell into even greater disrepair over the following decades. Every now and again Linlithgow Town Council would discuss the possibility of repairing the fabric of the pier so that it could be used by excursionist from up the Forth, and every time the matter was left in abeyance. Fed up of all the talk, some if the residents of Blackness got together in 1904 and set up a committee to raise the necessary funds. 25 trustees were appointed and John Blackadder, solicitor, acted as the secretary. Through a series of weekly concerts, exhibitions, dances, cinematograph shows, and the like, they accrued sufficient money to make a start. The Linlithgow Guildry promised £5 to the project, and so Linlithgow Town Council (the owners) reluctantly matched it. W M Scott provided the working plans. After a brief period of inactivity arising out of some hitch in the contract, the committee accepted an offer by David Rutherford, contractor, Grangemouth, and work was started in April 1906. Mr Ramsay, the proprietor of the Blackness Inn, started to run excursions from the pier in his motor launch in the summer of 1913. Amongst the sights that he promoted was the new naval base at Rosyth. The First World War naturally put an end to them. During the war the village filled with sailors on shore leave looking to explore the locality.

The work on the pier had been conducted on the landward end and was relatively superficial. By 1927 it was estimated that £200 worth of repairs were required to it. Once again Linlithgow Town Council questioned the point of retaining the pier, but the holes in the side faces were patched up and pinned with dry whinstone by its own workmen. The following year a large hole appeared in the surface of the pier and was also patched up. At the same time the Town Council leased the foreshore from the Board of Trade in order to promote tourism. For accountancy purposes the Council had the pier, harbour and foreshore valued in 1937 – the sum given was £200. However, the pier continued to deteriorate, and in 1939 large holes in the surface were filled with concrete aggregate. A storm in 1941 did more damage and eroded away 4 yards of the land to the west of the pier, biting into the road.

The pier was fenced off. The locals suggested that a bathing pool could be inserted between the pier and the Guildry. There were just two problems: at this point the war was still running, as was the sewage outfall. Linlithgow Town Council could see no use for the pier and had no money to spend on it. By chance the hotel at Blackness burned down in 1958 and the rubble was dumped into the pier – more to get rid of it than to consolidate the pier. Four years later a private individual with a boat there carried out some repair work – moving large boulders from in front of it and replacing some of the woodwork.

The pier and the adjoining area of foreshore, which had been valued at a little under £200 in 1927 was sold in 1972 to the Blackness Boat Club for the nominal sum of £1. The Club proposed to extend the pier and build a clubhouse. The pier become private but the foreshore was left open to the public. If anything happened to the Club the pier was to revert to the Council. The Club thrived.

The final act of vandalism came in 1960 when the old Guildry was replaced with a residential block by West Lothian County Council. The National Trust had been offered the building, but had its hands full elsewhere.

The stone pier was brought up to date by the Boat Club in 2010. In the 1970s the beach immediately on its eastern side had been reclaimed by building it up. Now a slipway was added forming an eastern pier.

Sites and Monuments Record

| Blackness Pier | SMR 907 | NT 0518 8009 |

| Blackness Castle | SMR 416 | NT 0554 8026 |

| Blackness Brickworks | SMR 638 | NT 050 798 |

| Blackness Tidal Mills | SMR 1022 | NT 0555 8000 |

| Blackness Castle Pier | SMR 1256 | NT 0556 8031 |

Bibliography

| Chalmers, G. | 1887 | Caledonia, or, A historical and topographical account of North Britain from the most ancient to the present times. |

| Gillespie, R. | 1868 | Round about Falkirk. |

| Hendrie, W.F. | 1989 | Linlithgow: Six Hundred Years a Royal Burgh. |

| Lesley, J. | 1578 | De Origine Moribus, et Rebus Gestis Scotorum Libri Decem |

| Livingston, E. | 1920 | The Livingstons of Callendar and their Principal Cadets. |

| MacIvor, I. | 1982 | Blackness Castle. |

| Sibbald, R | 1782 | The History and Description of Linlithgowshire. |

| Tucker, T. | 1824 | Report by Thomas Tucker upon the Settlement of the Revenues of Excise and Customs in Scotland, 1656. |

| Patten’s The Expedition into Scotland is reprinted in Dalyell’s Fragments of Scottish History and in Arber’s An English Garner. |