The recent discovery of an enamelled terret ring and a tankard handle dating to the decades around the birth of Christ, taken together with first century Roman brooches, the odd coin, and a lead weight, show that the Hill of Airth was an important locus of power in the Iron Age. It was strategically placed on the great coastal route connecting the Lowlands with the Highlands. It was also close to one of the major crossings of the Forth which for long operated from Higgin’s Neuck.

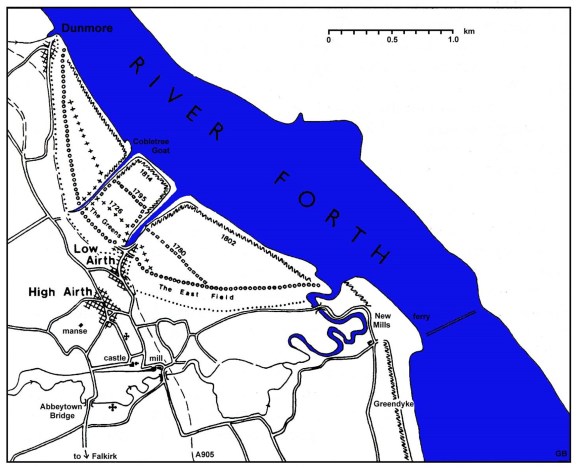

Three streams entered the Forth in this area. At the extreme south was the “Pow of Airth” which debouched at Higgin’s Neuck. It was the largest of the three and as it emerged at the southern arm of the bay it provided the shortest crossing point for the Forth. It was sometimes referred to as the “South Pow” to distinguish it from that at the burgh in the centre of the bay which was known as “Airth Pow” or the “North Pow.” A little to its north was the Cobbletree Goat which formed the boundary between the estates of Airth and Dunmore. All of these creeks were made use of by sailing vessels. Access to all three was by channels worn through the mudflats, though the flats at Airth Pow and Cobbletree Goat were much wider than at Higgin’s Neuck.

The wide sweeping bay between Dunmore and Higgin’s Neuck acted as a natural harbour and a small promontory at its centre performed as a pier. The Airth Pow gathered its water from the Hill of Airth and entered into the Forth along the west side of this promontory. The limited catchment area of the stream meant that it was not large. Its current was strong enough to create a channel through the mudflats or sleeches which could be used for shipping. Indeed, it may have been the presence of this stream that resulted in the formation of the small promontory on the east side of its mouth. There was enough water in the burn to still the tidal waters of the Forth at this point, allowing them to deposit their burden of silt and mud, but not enough to carry away that mud which did not lie in its direct path.

Just how early a working harbour was established at Airth is not known. Scottish records are sparse and one of the earliest references comes from England. In 1338 the people of Yorkshire were ordered to provide victual for the garrisons of Edinburgh and Stirling. The supplies were taken to Kingston on Hull and thence to the ports of “Leth and Erth in Scotia” (Reid 2002, 26). Twenty years later another English supply ship, the “Mandaleyne,” was at Airth. Unfortunately for the owner, Walter Curteys, the English army did not reach that burgh and consequently it was “plundered and stripped at Erthe” (ibid, 26).

It is not clear from these references whether the landing place was at the Airth Pow in the centre of the bay, or to the south at the mouth of the Pow of Airth at Higgin’s Neuck (also known as Newmills).

We do know that the medieval burgh was located a little to the north of Airth Castle and that latterly it contained warehouses for the storage of goods. By the late 17th century it was called “Haigh Airth” to distinguish it from “Laigh Airth” then rapidly developing at the mouth of the Airth Pow. The original settlement had evidently occupied the hilltop for reasons of security. It was close to the mouth of the Airth Pow (650m) but some distance removed from Higgin’s Neuck (1.7km). However, the volume of early coastal trade was slight and the comparative ease of access for ships to the Pow of Airth suggests that it was the harbour in the medieval period. By comparison we should note that the staple port for Falkirk in the 17th century was the Salt Pow on the river Carron – a distance of 2km away.

A charter by Archibald, Earl of Douglas, dated to 1409 granted the Lands of Hall of Airth to Sir William de Crawfurd,

“with the cottages, cruives and fishings of the said lands, and common boat of the harbour of Erth”

(Reid Notes).

This appears to favour the site at Higgin’s Neuck for the harbour of Airth. It was chosen in 1505 as the site of a naval dockyard by James IV (Reid 2002). This necessitated the construction of docks there to house the fleet of warships.

Coal mining at Airth began at a very early date and Pont’s map of c1580 shows a windmill near the Pow of Airth near Westfield. Roy’s map of 1755 shows that the road eastward from Westfield was called the Coal Gate. The road follows the lower land to the coast, thus avoiding the Hill of Airth. This brings it out to the Cobbletree Gote and it is probable that the coal was initially shipped from there. Confirmation that this was the case seems to come from the tack of the Lands called Kirkraw in 1582 (Reid Notes). The tack notes that George Bryce elder had leased the land in 1571 for the purpose of making a haven and port for bringing coal to ships there. From a later sasine we learn that the lands of Salterfield and Kirkrow, with houses, lay “between the moss and sea between the lands of Elphingstoune on the north and the earl of Linlithgow’s lands of Airth on the south within the regality of Airth” – which places them at the Cobbletree Gote.

John Bruce was served with the Lands of Airth in 1597 and it was erected anew as a burgh of barony. The charter includes a number of privileges:

“and erecting part of the lands near to the seashore, opposite the said John’s lands of Airth,- into the free Port of Airth, with authority to the said John to construct a mill and saltpan upon the seashore, the ferry boats on both sides of the Water of Forth, with the hevin-sylver, large customs, anchorage, and other duties levied at a free port;-moreover erecting the Town of Airth and all those parts of the land relating to the said John, into a free burgh of barony with free port; with power to the said John to elect baillies, burgesses, officers etc., and the power to the said John to set prices and have a market cross, and a weekly market with two free markets annually on 24 July and 8 October, with customs … “

The emphasis on commercial activity is notable and it is surely no coincidence that the year before John’s father had received a licence from James VI to export coal from his own collieries. Another licence was issued to Sir James Bruce of Airth and Alexander, Lord Elphinstone, in 1614, for the use of the harbour and port of Airth for the transport of coal and salt (Reid Notes). The Bruces evidently overstretched themselves, for in 1619 the barony was bought by the Earl of Linlithgow. The contract of 1621 contains similar conditions to those of the earlier charter:

“with the burgh of barony of Airth, port, the Pow, harbrie and hevin of Airth, salt-pans, salt-houses and the girnel-housis, with the freedom of fishing, privilege of moss, common pasture and the digging of fewall, faill and dovett within the moss and commonty of Airth outside the arable lands of Airth in common greens, with feues etc, and with all the coal of the lands contained within the said contract”

(ibid).

The ships of this period were relatively small and for cargoes of Great Coal that was helpful. The market for coal demanded it in large lumps; once it was broken into smaller pieces it was not as valuable. So it required careful handling and small shiploads so that it would not be crushed. This is clearly demonstrated in an agreement in 1614 between Sir John Bruce of Airth and a London merchant in which it stipulates that each ship “should contain 40 tons of coal and no more” and “all the dust or smaller coal be cast and not accepted” (Papers Clerk of Penicuik, NRS; quoted in Dickie 2023, 185)).

The 1597 grant of the status of burgh of barony is significant, occurring three years before that for Falkirk. It seems to have been at this time that Laigh Airth was started and the population slowly drifted down the hill to be nearer to the point of commerce based upon the new harbour. Trade was increasing exponentially at this time. As the Forth was not navigable to ships of large burden beyond Alloa, due to its shallowness and windings, Airth acted as the port for the Royal Burgh of Stirling. The Tucker report of 1656 produced for Cromwell as a guide to the coastal trade fails to mention Airth. By then Bo’ness was the principal port on the south side of the Forth and the report notes that for Stirling

“all goods are entred first, and cleered belowe at Burrostonesse, and thence afterward carried up in small boates as the merchant hath occasion for them”

(Tucker 1824).

It is curious that Airth did not merit a passing reference as even Dunmore (then called Elphinstone) is mentioned as a point for the export for coal, though it was emphasised that it was served by the Dutch and did not have its own vessels.

In the late 17th century Airth thrived with an established trade to north-west Europe as well as to the south of England. The main sources of income came from coal, fishing and salt-making, all of which were exported through a vibrant port. Agricultural produce, brewing, distilling, milling and the ferry also provided employment. The flourishing condition of this trade is reflected in the substantial town houses erected in the Low Town from the 1680s to the 1720s, some of which are still standing.

After the Union of the Kingdoms Airth harbour was annexed as a dependent haven, or member, to the port of Alloa, and Customs officers were appointed. This Commission dated to 1713 and was worded thus:

“And we do Assign and Appoint the Town of Airth to be another Creek belonging to the said Member Port of Alloa and that Whatever Goods Wares or Merchandize Shall be Exported into or Out of the said Creek and that the Limits of the said Creek of Airth shall Extend from the Said Pow or Inlet of Waters to the said Point called Reddy Haugh Point to the West, and to the East Side of the Burn or Pow of Newmills at Haiginsnook East…”

(quoted in Sharp)

.

Charles Elphinstone had succeeded his father, Richard, in the lands and Barony of Airth in 1683. A new market cross was erected by him in the Low Town in 1697; the head displaying his initials and coat of arms, and those of his father and mother. The other two sides have sundials, and one of them has the date 1697 – a century since the burgh status was renewed.

.

The lands and barony changed hands again in 1717 when James Graham, advocate and judge, acquired them and again the Port and Harbour (Portu et navium Statione) are mentioned. James Graham had done well for himself.

He studied law at Louvain, became an advocate in Edinburgh, and in 1702 received his appointment as Judge Admiral of Scotland from the Duke of Lennox, the hereditary Lord High Admiral. The court in which he sat tried all maritime cases. The Judge’s first wife, Marion Hamilton, having died, he married secondly Lady Mary Livingstone, daughter of Alexander the third Earl of Callendar.

“Una cum privilegio et jure liberae baroniae, omnium et singularum praedict. terrarum aliorumq. ante specificat, cum burgo baroniae de Airth, portu et navium statione ejusdem, et cum omnibus et singulis, privilegiis, libertatibus, immunitatibus, casualitatibus et pertinen. dict. baroniae, portus, navium statonis, aliorumque antea script, infra bondas antea specificat; ac etiam totas et integras“…

which translates as “and harbour and station of ships of the same, with all and singular privileges, liberties, immunities, casualties, and pertinents of the said barony, burgh of barony, harbour, station of ships, and others before mentioned, within the bounds of the same”

Airth was at the height of its prosperity and the 1720s saw much substantial building there, including the tolbooth and fleshmarket. Johnston of Kirkland described the scene at the port in 1723:

“Here is a dock for the building of ships, a saw miln, which goes by wind of a figure never before seen in Scotland invented by the ship builder himself, and a harbour called the Pow for ships of very considerable burden, which are built here very ingeniously and frequently as in any dock in the firth.”

John and Charles Duncanson, ship builders, are found at Airth in 1726 and so they were presumably the ingenious men whom Johnston was speaking of. Their yard was at the Old Smithy at the north end of Shore Road with a slip into the deeper water of the harbour, though smaller ships were also built at North Greens where John lived, almost 300 yards to the west up the pow. These latter vessels had to be dragged over the mud to get them to the water. The last ship to be built at Airth was the Lilly, a sloop of 66 tons, by John Duncanson junior in 1785. Robert Adam is also mentioned at a shipmaker in 1739.

| YEAR BUILT | SHIP’S NAME & DETAILS | OWNER AND MASTER | REF |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1720 | Betty – sloop 48 tons burden, for sale at Leith December 1725, Capt Hamilton. | CM | |

| 1733 | Mary – brigantine of 50 tons | AP | |

| 1733 | James – doggar purchased in Mandel, Norway, and rebuilt at Airth | James Connochie | Cus |

| 1739 | Anny, 44ft long keel, 15.5ft broad in the beam. | Robert Adam builder | AP |

| 1744 | — sloop 36ft keel, 14ft broad & 7ft under beam Oak. | Charles Duncanson for James Garnoch | AP |

| 1750 | Isabel – sloop 57 tons deadweight, 39ft 9ins keel, 15ft beam, 8ft 4ins deep hold. Timbers of Norway oak… | Alexander Crockat, Kincardine, master, built by Charles Duncanson | CM |

| 1750 | Greenock – sloop of 70 tons. | J Scott & Co | IB |

| 1750 | Grizzel – 70 tons burden | Ely | EEC |

| 1751 | William – square sterned brig of 90 tons | EEC | |

| ?? | Helen sloop 80 tons. | G Harries of Leith | |

| 1764? | Peggy – sloop of 70 tons. | JN Walker & Co of Leith, Bicol Currie master. | IB |

| 1765 | Ann Shaw – sloop of 55 tons burden. | CM | |

| 1785 | Jamie & Jenny – sloop 37 tons. Broken up 1887. | Benson of Carron Co. | IB |

| 1785 | Lilly – sloop 66 tons | Lost in Forth & Clyde Canal c1818. | IB |

Norwegian oak was imported for the building of the ships. As well as building them from scratch other vessels were brought to Airth for rebuilding or overhauling. Repair and maintenance work was also undertaken.

The range of material traded was diverse. For example, we know that “upwards of ninety barrels of extraordinary fine whale Speck” (diced whale with the skin and muscle removed) “prepared for Refining” were sold in the house of James Henry, clerk, in Airth in 1726 (Caledonian Mercury 21 March 1726, 4). 90 hogsheads of lint seed landed at Airth by John Dunlop, merchant in Rotterdam, in 1750 were condemned by the Justices of the Peace as unfit for sowing and were sold off for turning into oil (Caledonian Mercury 1750, 4). Cut wood imported from Gothenburg was stacked on the shore of Airth for sale in 1768. Wine came from the northern coast of Spain and indeed a part of Airth, at the west end of the town, was for a time known as “Bilbao.”

Smuggling was indulged in by the Airth ships. Duties on coal, iron and tobacco were manipulated by giving false weights and paperwork and Customs officials were bribed. The big profit was on spirits such as brandy and inevitably the large amounts of money involved led to violence. In March 1720 the Elizabeth & Joan of Airth put into Alloa to register her cargo with the Customs, before setting off for Rotterdam. She was searched and goods were seized, but then a mob attacked the officials and carried off the prohibited goods. Several such deforcements then occurred at Airth to such a degree that it threatened the regular trade there. In May 1723

“about One O’ Clock their came above a Dozen of fellows aboard of the Wine Ship, Forced our Officers into the Cabin there, kept them Prisoners, the space of an hour some of the Tydsmen came to me a little after two and told me what had happened, I asked if they heard the Locker go and they said not which makes me think that the Seamen has had some Anchors aboard which they have been taken out and that which confirms is that Clerk & Linn who is the Merchants, cursed them and said if Mr Graham did not find a way to put a stop to that way of doing, that no man would continue to bring any more Ships to Airth, and he likewise said it to Mr Graham who came down upon the hearing of in full rage and anger and was at great pains to find out the Actors, and being difficult with them being all Blacked none of the Tydsmen could know them”

(Sharp, 15).

It was discovered that part of the problem was corrupt officials – the tides-men pretending that they had been deforced and locked into the cabins. They were sacked and replaced. The number of tides-men was increased but still they were deforced, leading to this reaction in April 1730: “We are at a loss how to behave with respect to the Creek of Airth having now used all means that we could devise for the security of the Revenue at that Place, and after all to little purpose. In regard the Officers are continually Deforced there and we have all reason imaginable to look on this present Deforcement as done by Airth People. And we humbly think that there is only one way left untried that might in some measure put a stop to the smuggling there and that is the joining some of the Military with the Tydesmen on Board ships as we have come to suspect coming to that Port from Foreign parts Especially from Holland, And if your Hon’s will be pleased to give your Directions to this purpose it will certainly lend much more for the Interest of the Revenue than any charge occasioned by the Military so employed can sustain from it.”

(Sharp, 62).

With some difficulty, this suggestion was taken up, and on 8 April 1734 there was a more optimistic note:

“Notwithstanding of Major Moreau’s letter recalling the Soldiers, he was pleased to allow for their staying at Airth for a months time, they suffered an abundance of fatigue, and behaved very well, and hitherto hath had no more than about sixpence a day each of them. The Dutys already received out of the Ships attended by them, and to be received for the Goods in the Warehouse and which in a great measure is owing to them, will amount to more than hath been collected on Goods since I was concerned. Besides that of the Norway voyages, a few of which would put an end to that pretended lot of Smugglers. It’s therefore hoped your Honours will be pleased to allow them something extraordinary on account, seeing they expect it. And that a sum not exceeding £3, will do much to satisfy them”

(Sharp 80).

The optimism was misplaced and as soon as the troops were withdrawn the deforcers were back in business, only now they were more desperate and used greater force.

7 May 1734 – “James Corrie and John Troup, two of the Tydesmen that attended are most Injuredly beaten and bruised to that degree that none of them will be able to do duty for some time, and the aggressors are also hurt, But how to discover the answers I am at a loss to understand, unless James Mackie and William Borrowman two of the Ships crew, at whom the precognition seem to reveal most were taken up and the rest used as Evidence against them.

I humbly beg leave once more to offer it as my opinion that the Officers can be of little use there on any occasion without Military assistance.”

(Ibid, 81)

It was found that by using soldiers from Stirling Castle when the smuggling was suspected – they knew the ships and crews involved – it was possible to considerably reduce this clandestine practice. The large increase in revenue from taxation and confiscated goods paid for the military presence – as long as the soldiers did not get drunk.

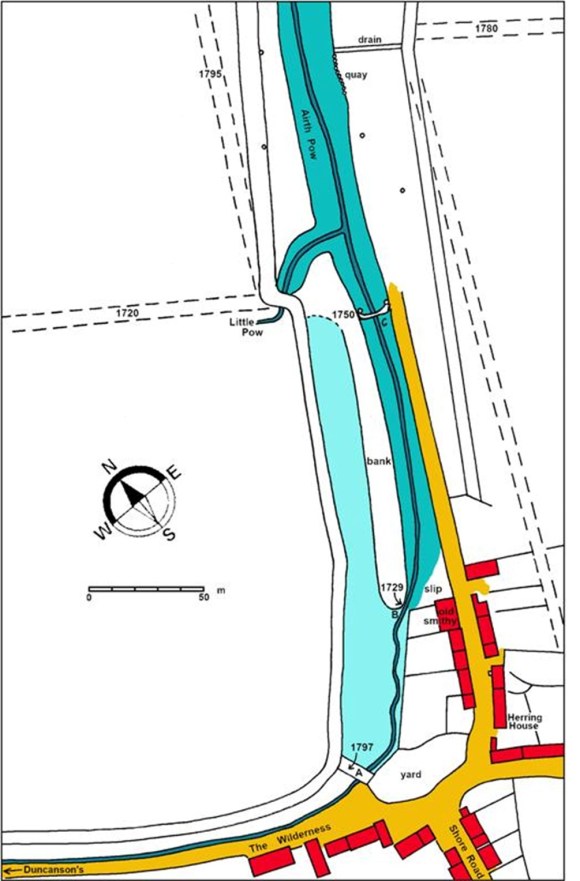

In 1729 the financial accounts in the Airth Papers contain several references to a new pier and sluice. The use of the term “new” shows that they were replacing existing ones. This is confirmed by one very brief mention that gives more details. From this we learn that there had been a reservoir with a dam, and that a “spout,” in other words a wooden pipe, led from the dam to the pow. This suggests that the early pond lay a little removed from the pow, probably a little west of the later parish church in Graham Terrace. From there it led down a slight slope to the harbour. This section was long enough for it to be called the “Spout Burn.” The probable site of the sluice before 1729 is shown as “A” on the plan below.

It appears that the new sluice of 1729 was constructed in a dam across the line of the pow creating a basin at its upper end. The probable site of this sluice is shown as “B” on the plan below. The dam needed a wooden foundation due to the soft sediments, and had an upper wall of Longannet stone. The dam of the old reservoir was built up so that the water it retained could act as a topping up supply. The need for the change in location was probably a result of the initial land reclamations in this area which dated from the late 17th century (see Land Reclamation from the Forth). One of these banks was now used to form the west side of a shallow new reservoir which consequently in part ran parallel with the course of the pow north of the new sluice.

The new sluice had to be maintained and there is a record of a repair in 1735. The year before that a heavy rope had been bought for it. This would have been for the windlass which was used at that time for lifting the sluice paddle. The stonework needed attention in 1747 and Patrick Walker was provided with peat so that he could burn limestone for the lime mortar. This was evidently just a patch, for in June 1749 Archibald Handyside, mason in Musselburgh, inspected the sluice and harbour of Airth and estimated £200 for repairs and a new floodgate to the sluice. The local shipmasters expressed their support for this work to be done. Their support was essential as it is clear that it was the shore dues that helped to pay for the improvements. Alexander Fiddes was appointed as shore waiter and oversaw the project. The extent of the work on the sluice can be judged from the fact that it took 115 carts of stone from John Duncanson, smith in Airth. The new floodgate was located about 150 yards down the pow from the old one, nearer the Forth (Point C on the plan below) and opened by tooth and pinion. The floodgates took the form of lock gates so that the basin was essentially a wet dock. The gates had wickets opened by tooth and pinion for cleaning the harbour to the north.

Alexander Fiddes was the sub-factor for the Airth estate owned by the Graham family. He hired men to attend to the opening and closing (the drawing and shutting) of the sluice and for collecting the shore dues. The sluice required frequent repairs. By 1762 the shore dues and the customs of the burgh were being let to private contractors. Here is the letter of acceptance by one of those contractors dated 8 July that year:

“I accept your offer of the shore dues and customs of Airth on the following terms. I am to pay you five pounds sterling per annum to allow Mr Chalmers to bring in any quantity of victual exceeding 5,000 bolls at the rate you wrote to Mr Higgins, to uphold the sluices in the same repair I get them, excepting stone or timber which you are to furnish, I am to pay the drawing the sluices the last two years and you to pay the first“.

The broad sleeches off the coast meant that most vessels hired pilots before attempting to navigate the waters of the upper Forth. In January 1751 the Adventure, of and from Lynn, was bound to Airth with a cargo of oats. It anchored off the coast at Leith and the master with his son and three sailors went ashore in their boat, leaving only one man on board, in order to agree with a pilot to carry the ship to Airth. Having procured Hugh Stamfield, formerly a Ship-master in Leith, they put off again in the evening for the ship; but a gale of wind overset the boat and all perished (Newcastle Courant 12 January 1751, 2).

The pale blue area was the reservoir. The old sea embankments are dated according to when they were constructed.

| NAME OF SHIP | KNOWN DATES | MASTER | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clemintina Marion | 1731 | William Eason & Robert Adam | |

| Amy | 1731 | ||

| Anne | 1733-1747 | James Walker Patrick Walker | square sterned brigantine 50 tons burthen |

| Primrose | 1733- | Andrew Ross | 60 tons burthen, two masts. |

| Mary | 1735-1740 | James Mackie | Lost 1740 off Dunglass, most of crew drowned. |

| Blacksmith | 1746 – | Barriman | |

| James | 1747-49 1749 | Bauld James Mackie | |

| Betty | 1747-53 | John Connochie | Snow of 150 tons. Taken by French privateers 1747 and ransomed for £750. Sold 1753. |

| John | 1748-51 1754- | Robertson Connochie | |

| Anne | 1748 | Hodge | |

| Helen | 1748 | Garnock | |

| Janet | 1748 1753 1767 1775 1777 | Hutton Mackie McEwan Stuppart McCappy | Brigantine |

| Mary | 1749-63 1750 1754 1776 | William Anderson Younger Connochie Parker | |

| [unknown] | 1750 | Alexander Logan | Lost near Lerwick in Shetland; 7 passengers and 5 crew perished; the master and a boy were saved, being cast on a rock by the waves. |

| Charming Sally | 1750- | William Hodge | Attacked by privateer 1756 |

| Margaret & Jean (Mary & Jean) | 1750 1771 | John Mackie Watson | |

| Janet & Mary (Janet & Margaret) | 1750 1756 | Adams | |

| Crown | 1750 1751 1753 | David Grey Mackinson Liddell | Square brigantine of 40 tons burthern |

| Robert & Mary | 1754 | Dewar | |

| William | 1754-1755 1756- | John & Patrick Dick Garnock | sold £180 |

| Elizabeth & Janet | 1755 | Anderson | |

| Grizzel | 1755 | Mackinson | |

| Elizabeth | 1756 | Patrick Dick | Taken by privateer and ransomed 1757. |

| Lady Janet | 1758 | Dick | |

| Alexander & Jean | -1758 | Daniel Dewar | Collision with the Dolphin of Bo’ness whilst in convoy. Vessel lost at Scarborough 1758. |

| Margaret | 1759 1760 | Dalrymple Nicol | |

| Penelope | 1759 | Logan | |

| Carmichael | 1760 | Stuppart | |

| Robert & Mark | 1760 | Daniel | |

| Christian | 1761-67 1767-68 1772 | Cowan Wood Brown | 150 tons burden, for sale 1774. |

| James Graham | 1762-64 | Dalrymple | |

| Friendship | 1766-1776 | Logan | |

| Peggie | 1766 | Mathieson | |

| Lovely Ann & Mary | 1766-67 | Adam | |

| James & Mary | 1766 | Watson | |

| Henry | 1767 | Connochie Masson | |

| Dunmore | 1767-68 | Hodge | |

| Peggie & Mary | 1767 | Bald | |

| Ann Shaw | 1768 | Sloop of 55 tons burden, for sale. | |

| Concord | 1771 | Stark | |

| Lovely Twins | 1767-75 | Campbell | |

| Elizabeth & Margaret | 1771-1776 | John Watson | Sloop of 70 tons burden for sale. |

| Margaret & Mary (Margaret & Marion) | 1774-75 | Higgins | |

| Charlotte | 1776 | Bald |

Here Rests the Body of Captain

JOHN DICK who died the 16th

jully 1795: aged 57 years.

The winds and seas full forty years

Have tost me to and fro:

in spite of those by Gods Decree

I anchor here below

There were quite a large number of shipmasters/skippers in Airth in the 18th century. These included John Adam, Robert Adam, Anderson, William Anderson, Bauld, Campbell, John Connochie, Cowan, David Cuthill, Dalrymple, Daniel Dewar, John Dick, Patrick Dick, William Eason, John Forrester. Patrick Forrester, Garnock, David Gray, Higgins, William Hodge, George Hutton, Liddell, Alexander Logan, John MacAlpine, McCappay, James Mackie, John Mackie, Mackinson, Masson, Mathieson, Nicol, Parker, Robertson, Andrew Ross, James Shaw, Stuppart, James Walker, Patrick Walker, David Watson, John Watson, Wood and Younger. Each of these would have had families in the town, many of whom would have helped to crew the vessels. There would have been at least three sailors for each captain and it was they who normally loaded and unloaded the cargoes. The voyages were arranged by merchants based in Airth, and lawyers or clerks there.

The Airth Friendly Society was a mutual assurance society which paid out in the event of a death on a trip. It had a meeting place in the Low Town called the “Box House” after the wooden chest in which the money was deposited. Before a trip wills, agreements, and contracts, were deposited with the baron court in the tolbooth. Some of these were acts of factory placing spouses in charge of their home affairs. The ships too were insured, as in this example from 24 February 1741:

“John Conachy, shipmaster and master of the “James” of Airth owed £27.2 to David Gregory merchant in Middlesborough for the £1000 insurance premium of his cargo from there to Airth. This was composed of:

- insurance at 2% ………. £20.-

- brokerage …………….…. £1.10

- for the police ………..…..£-.12.-

- Commission at 0.5%…… £5.-“

Ownership of the vessels was divided into shares in order to spread the risk amongst the community. The ships were based at Airth and so it was here that they got basic provisions and supplies. It was here that non-urgent repairs were carried out. Most of the time the ships were travelling from port to port, picking up cargoes as they could, and spent only short spells in their home port. Some over-wintered at Airth. Cargoes collected from Airth included wood, coal, grain, tar, passengers, and iron. The coal was delivered to the harbour in bags – there being no waggonway. In 1723 a land-waiter and a tides-man were employed to pick out bags at random and weigh them in order to calculate the ship’s cargo and hence the tax due. The export of iron was interesting as it was largely confined to 1768 when the river Carron was being straightened and access to the harbour at Carronshore was difficult (Grangemouth had not then been established).

With so many sailors in the town it is not surprising to hear that the press gangs visited. On one of these occasions a seaman was standing at the Tron near the Cross when he suddenly realised that he had been surrounded by some burly men who were closing in on him. To their surprise he made a sudden bolt into an adjacent close, got the door shut and barred, and betook himself to the fields. There he found a pair of horses attached to a harrow and hastily unloosed one, mounted it bare-backed, and galloped off. He is said never to have halted till after he had crossed the Carron, leaving his pursuers far out of sight, though not out of mind (Stirling Observer 21 May 1857, 3).

There was an oft told story of another sailor, by the name of Spence, getting more than he had anticipated upon his brief visit to Airth. His vessel arrived at Airth and lay up for a day or two. In that short space of time he became acquainted with a girl of the name of Laidlaw and they plighted their troth. Before setting sail he gave her an antique ring which was a family heirloom. Shortly afterwards she was attending the Episcopalian church in the town, wearing the ring, when a youthful seaman sat beside her. On returning home she discovered that the ring was gone. Weeks became months, and months became years, and she heard nothing from Spence. Spence had been visiting many foreign ports and at one he met a fellow sailor from Scotland. Upon entering into conversation with him his eye rested upon the gem upon the hand of his newly-acquired acquaintance. He recognised it and immediately asked how the stranger had come by it. After telling of his visit to the church, the young seaman said that he had found the ring which had fallen from her finger, but did not have time to return it before he had to set sail. Three months afterwards Spence arrived at Newcastle and proceeded to Airth, and got married. The couple left Airth shortly after (Stirling Observer 14 May 1857, 2).

1745-46 were epic years for Airth. The Jacobite army marched through the village in September 1745 on its way to Edinburgh and retained control of the area for some weeks before a Hanoverian resurgence. The Government used this brief interlude to remove all of the vessels, of whatever size, from the area so that they could not be used by the Rebels. All except two “skiffs” which had been laid up at Airth for the winter. There they were to undergo repairs in preparation for the next season and so were dragged up the muddy slopes at the head of the harbour out of reach of the ordinary tides. Scaffolding was placed around them, which is why some accounts refer to them as being on the stocks. The Jacobites were back that December and on 4 January 1746 Pitsligo’s Horse were stationed in the town.

The Government forces now blockaded the Forth to prevent the Jacobite cannon from reaching the besieged castle at Stirling. It was able to take expert advice from local supporters, including Walter Grossett who worked at the Customs House at Alloa. He was very familiar with Airth having dealings with the smugglers there. He was evidently concerned that the Jacobite army might try to haul the skiffs back over the mud into the water. On 8 January the Government sloop, the Vulture, was off Airth and sent two longboats with soldiers towards the town. They must have landed at the sea dyke to the west of the pow and used the embankment to reach the skiffs. This effectually shielded them from the Jacobite troops in the town and put the broad channel of the pow between them. The sloops were high and dry – the latter being a quality that made them ideal for burning. They were torched and the landing party returned to the longboats being ineffectually fired at by the enemy. They reached the Vulture without any injury. In the interval, however, the tide had turned and the Vulture was stranded.

That night, three 4-pounder cannon from Stirling reached the Jacobite army at Airth with an engineer, Colonel Grant. Without losing time he had a battery erected and at first light they opened fire on the unsuspecting sloop. Upon recovering from the shock the crew of the Vulture returned fire with its large guns and succeeded in putting them out of action before sailing off.

That night one of the most daring raids of the campaign was launched by the Government forces. A raiding party consisting of three small vessels was sent up the Forth to clandestinely land at Kersie to capture Lord Elcho who was billeted there. They were guided by two local pilots – Adams of Airth and Morrison of Leith. The task force made it undetected to the house, only to discover that their quarry had left shortly before for Airth. They then made for their secondary target, a Jacobite brig on the other side of the Forth at Alloa. Unfortunately for them the extra troops on board increased the draft and one boat grounded on a mud bank in mid-channel. By the time that the tide was able to carry them off it was almost light and the enemy batteries at Alloa and Dunmore opened up. Despite being small fast moving targets across a flat elevation the boats were hit by the skilled gunners and Morrison and Adams each lost a leg, dying within the fortnight. The main theatre of action then moved elsewhere and before long the Jacobite threat had been lifted.

Skiffs were amongst the smallest of seagoing craft, though it was evidently felt that those at Airth were sufficient to carry small cannon. Unfortunately, we cannot be sure that the use of the term was not propaganda by the government sources to minimise the mercantile loss and diminish the Jacobite resources. The minister of the parish, in 1793, wrote that “The loss of these vessels were severely felt by the trading people in Airth, and trade has since removed to Carronshore and Grangemouth.” He was not an impartial reporter and it is clear that smuggling and land reclamation played far larger roles in this shift, as did the foundation of the Carron Iron Company and the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal.

At first the Carron Company was happy to use the harbour at Airth for its coal from the Kinnaird Colliery in 1762. The carts must have followed the Lang Dyke to the Abbeytown Bridge before skirting the Hill of Airth. However, the development of Carron Wharf at Carronshore much diminished to role of Airth.

More land reclamation took place and the sluice, harbour and pow fell into disrepair. The dock gates decayed to such an extent that when the Lilly was floated out – last ship to be built at Airth – they practically fell apart. Complaints from the shipmasters meant that the sluice was rebuilt at the same spot in 1786-7 by Alexander Turnbull. Shaw’s map of 1810 shows a substantial wall with a curving seaward face which would have braced the water retained behind it. A sluice was still opened by tooth and pinion but now ships could not pass it. Drains that had previously run north from the Hill of Airth were diverted into the Airth Pow in order to augment the supply to the harbour – though some of this was diverted for domestic use in the town. As well as the previous wet dock, the low-lying field was used as a shallow reservoir. The main source of water for sluicing came from the high tides and spring tides were particularly useful in this respect. When the sluice was ready in 1787 it was noted that 5ft of mud needed to be cleared out and that six men were to be employed at the following spring tide to help. They were probably employed down the course of the pow loosening mud with spades so that it would be carried away by the water from the sluice. The lower end of the pow was straightened so that the water would more effectively sluice out the mud – and so that more land could be reclaimed. During the period of disuse the shore dues had not been collected and so in 1789 William Graham decided to reintroduce them to use the money to maintain and regulate the sluice. Due to William’s death it was 1792 before James Williamson was appointed to collect the tax. The pent up water in the basin was released twice a day at low tide to flush the harbour, which now lay to the north of the static dam in which the sluice was located. The effect of using the sluice was to provide a depth of 7ft of water in the harbour at the head of the pow at neap tides. This allowed vessels of 30 or 40 tons burden fully loaded to reach it. To aid future sluicing and cleaning operations the pow immediately to the north of the sluice was lined with planks. The road along the east side of the pow was extended northwards and a new stone quay was constructed using wooden piles. Up to the 1790s brigs of 150 tons were able to reach the quay. The planking of the base of the pow proved useful to masters cleaning – breaming or careening – the hulls of their vessels . During neap tides they would allow the vessel to rest on the bottom of the pow and the solid base made it easier for them to walk about. At the Clackmannan Pow, on the north side of the Forth almost directly opposite, a curved stone paving was used (Dickie 2023).

As the incoming tide was stronger than the current from the river there was a tendency for the channel of the rivulet across the mudflats to drift to the west. This lengthened the approach and the uncertain nature of the course made navigation more difficult. For the purposes of clearing the silt out of the harbour a shorter and straighter channel was necessary and so periodically, around once a decade, the local inhabitants were called upon to assist in cleaning it out and straightening it. The fact that this was seen as a feudal duty of the people of the barony suggests that it had been going on since at least the late 17th century. In 1733 drink was provided by the Grahams for the tenants and cottars cutting and cleaning the pow; and as late as 1800 bread and ale were given on a similar occasion. On one such operation scaffolding was provided. During the work the sluice was kept open so that mud loosened by spadework would be carried away by the running water. Latterly the work seems to have been contracted out, though tenants were still called upon to assist; and fishermen had their shore fees reduced if they helped.

| George Montgomery | 1749-1753 |

| John Cuddie | 1751-1787 |

| George Dick | 1755 |

| Michael Scobbie | 1787-1800 |

| John Hutton | 1795-1804 |

The last person to operate the sluice was John Hutton over the period from 1795 to 1804. He was given the key by Alexander Cumming who acted on behalf of the Grahams. During spring tides he opened and shut the sluice twice a day and this kept the harbour clean. For this he received the shore dues and the customs exigible upon the fair day in the town of Airth, but the latter never amounted to more than 1s. Vessels with lime and limestone of 30-40 tons burden were able to journey up to the quay. Over the winter of 1796/7 three brigs over-wintered at the head of the pow. One of these belonged to Glen of Forganhall, another to Kincaid at Bellsdyke, and the third to Scott in Airth. Very few vessels from outside the barony used it at that period, except herring boats and those of Stein who operated the distillery from the opposite side of the Forth. Stein found the harbour was essential for his trade and from Airth the whisky was carted overland to Glasgow. He agreed to give Hutton 13s 4d annually as shore dues, but generally rounded it up to 20s thus giving Hutton an annual income of roughly 30s for the work.

Around 1800 an earth bank was placed across the upper reservoir (A on the plan) by Alexander Cumming in order to prevent the road and the northern end of the village flooding at high tides. He had a vested interest in this because he had taken over the occupancy of North Greens.

Improvements and repairs to the sluice continued until 1800 when the revenue from the harbour was so poor that the Graham family resolved to abandon it and concentrate upon more land reclamation. Hutton was told to stop operating the sluice in 1804. A stake and rice fence was erected across the harbour, and a second one placed across the pow 60yds further down. These trapped more mud and before long the waterway was unusable by even small vessels, putting the remaining shipping concerns out of business. The herring fishery had used sloops, but these found it impossible to navigate the fences. Switching to open boats proved futile and, although the fences were temporarily breached, the businesses were obliged to move elsewhere. The harbour was then being used by Mr Stein of the Kennetpans Distillery on the opposite shore of the Forth. One of his two boats, the Mary-Anne – a strong boat with a mast, mainsail and foresail – often carried 8 or 9 puncheons of whisky. Meal ground at Kennetpans was also landed at Airth to be taken on to the Glasgow market. Stein insisted on the harbour remaining open and looked after. In 1807 he asked that the key to the sluice be handed over to him so that he could arrange to get it put back into working order. He also suggested that he be allowed to collect the shore and harbour dues to pay for its operation. By 1810 John Smith found that he could not even get his empty salmon fishing boat out of pow due to mud. Stein took Graham to court and the case was heard between 1809 and 1813. An interim interdict ordered Graham to remove the stake and rice fences. However, when the final verdict came it found that Graham was not obliged to spend more on the harbour than he received in shore dues. By then there were no vessels using the pow and so no shore dues. In any case, Stein had an alternative – he could use the Forth and Clyde Canal.

Despite this verdict there were still hopes that the lower end of the pow could be used as a harbour and in March 1823 James Jardine, civil engineer in Edinburgh, produced his report in which he states:

“The sea embankments on each side of the harbour and Pow, shelter the tidal waters, and enable them to deposit more mud than they would have done in their original exposed situation. Hence, the Harbour would now require all the land-water, and a larger scouring basin than formerly, to maintain as great a depth of water in the harbour, as it had before…” Levels taken. “Were the scouring basin cleaned, and the ‘bank between the basins’ removed, the sluice put in a proper state of repair, and regularly opened and shut, all the land-water continued to be conducted into the Pow, and the remaining parts of the staunches entirely removed, the former depth of water might be restores nearly, but not entirely, to the harbour of Airth; since the dykes along the sides of the Pow, and the continual retreat of the sea, operate more powerfully now than formerly in silting up the Pow and harbour.”

It was a hopeless case.

1857 witnessed what was probably the last launch of an Airth-built vessel. On 16 December a small craft of about 18 tons burden was placed upon a waggon and conveyed from the building-yard of James Martin at Airth to Dunmore, where it was safely launched in front of a large crowd. The yard was at the north end of Airth and the progress of land reclamation there had made it impossible to perform the operation there (Stirling Observer 24 December 1857, 3).

The farmers tenanting the low lands in the immediate vicinity of the old harbour often had their ground inundated by the bad condition and worn-out state of the tunnels that let water out at low tide by means of clap valves. To obviate this, “large and very superior new one[s]” were put in through the sea walls in 1860. At the same time, the Airth Pow leading to the old harbour, which had nearly silted up, was cleaned, to give a level to the various drains to run into. It was now little more than a glorified drain! (Stirling Observer 9 August 1860, 3).

Just a few years later, in 1865 the Ordnance Surveyors note on the harbour says –

“William Graham Esq., Airth Castle, principal proprietor. What is known as Airth Harbour is in a dilapidated state that even small boats cannot approach it with safety.”

The 1860 Ordnance Survey map in fact shows a jetty protruding out into the Forth itself from the sea bank.

Writing in 1770 the minister of Bothkennar foresaw the demise of Airth as a port –

“The village of Airth was formerly the chief centre of sea-trade in the shire we are surveying; but, during the course of the last fifteen or sixteen years, it hath transferred to Carron Shore, a small village, newly erected upon the river of that name. Nor does its settlement there promise to be of any long duration; for it hath already begun to remove to the Sealock, at the entry of the canal, which bids fair to be its great and lasting resort.”

(Nimmo 1770, 453).

Sites and Monuments Record

| Airth Old Harbour | SMR 889 | NS 899 878 |

| Airth Tolbooth | SMR 1385 | NS 8992 8752 |

| Airth Burgh | SMR 1386 |

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 1996 | Falkirk or Paradise! The Battle of Falkirk Muir 17 January 1746. |

| Dickie, M. | 2023 | ‘Clackmannan Pow; an early 17th century stone-built harbour,’ Forth Naturalist & Historian 46, 184-193. |

| Nimmo, W. | 1770 | The History of Stirlingshire. |

| Reid, J. | 1999 | ‘The Lands and Baronies of the Parish of Airth.’ Calatria 13, 47-80. |

| Reid, J. | 2002 | ‘Polerth: the lost dockyard of James IV,’ Calatria 16, 23-44. |

| Sharp, J. | n.d. | Extracts from the Alloa Customs Records; 1718 to 1750. |

| Tucker, T. | 1824 | Report by Thomas Tucker upon the Settlement of the Revenues of Excise and Customs in Scotland, 1656. |

| Ure, R. | 1793 | ‘The Old Statistical Account of the Parish of Airth,’ Calatria 1 (1999), 109-116. |