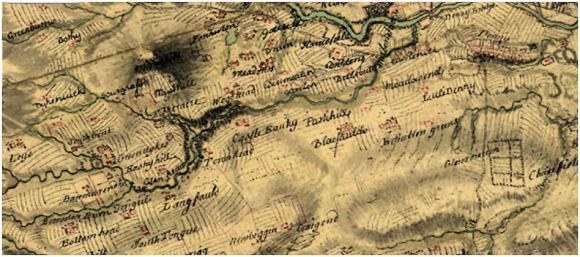

The site of Castle Rankine lies about 1¾ miles west-south-west from Denny town centre on the hills leading up to Denny Muir. It is on the 130m contour, 30m higher than the town. The castle occupied a crook on the Castlerankine Glen which here changes from a northerly orientation to one veering eastwards – the valley thus affording protection from the west and north. The fortifications stood on the southern lip of the escarpment that plummets down by a series of rock faces into the valley and the burn some 90ft below. The southern and eastern approaches were gentler and the site occupies a slight rise with a wide natural hollow curving around it.

The ancient route from Castlecary to Denny and Stirling lay a short distance to the east and the location of Castle Rankine was a little isolated. It seems to have been chosen with a consideration of defence and to provide access to the vast tract of grazing land. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries it was one of the principal centres of the Barony of Dunipace which was the second largest barony in East Stirlingshire. Presumably the main residence was the motte at the Hills of Dunipace. In the past the barony included parts of Stenhouse and Kinnaird, but these eastern lands were quickly separated off. The superiority of Dunipace in the thirteenth century was held by the de Unfravilles, but the greater part of the land was held as a feudal tenancy by the family of Malherb, or de Moreham as they were often titled. It must have been this latter family who were responsible for the construction of Castle Rankine.

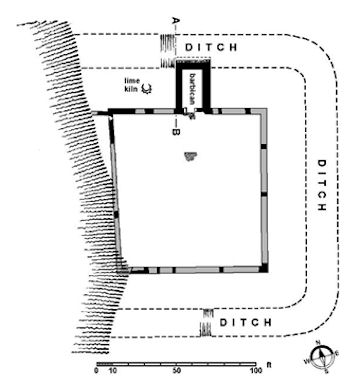

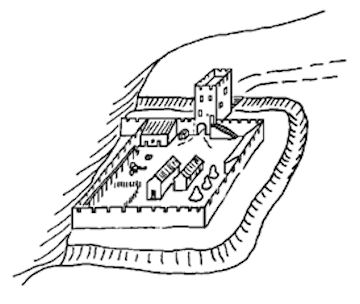

No sign of the castle now appears above ground but archaeological excavations in 1938 recovered most of its plan. It consisted of a quadrilateral enclosure surrounded by a curtain wall and a ditch. Projecting outward from the north side of the curtain wall was a stone tower or barbican which presumably contained the main entrance.

The trapezoid walled enclosure measured, along its inside faces, 93ft along the north side; 95ft 8in east; 88ft south; and 97ft west. The foundations of these curtain walls varied from 3ft 9in wide to 4ft 7in and had been laid in a 9in deep trench. Little of the upper masonry survived, but it was raised in dressed stone courses of about 9ins high. It is not known if there were small towers at the corners. A spur wall runs off the north-west corner to the top of the ravine, with a possible doorway at the north end of the west curtain wall. As the south-west corner of the enclosure was anchored on the edge of the escarpment it denied access to this area from outside. Traces of cobbled surfaces and timber buildings occurred within the enclosure and it is reasonable to assume that there were leanto structures against the curtain.

The barbican extends from the north curtain to the lip of the ditch and measures 28ft 6in by 21ft 7in overall. Here the foundations were between 5ft 5ins and 4ft wide and the walls above them were 3ft 8ins thick, supporting a tower. The large stone bases for the jambs of the doorway into the court lay towards the west side of its south wall and indicate a gateway of around 5ft in width. The western of these base stones housed a socket, 3½in in diameter, for the pivot of the large gate. The equivalent entrance in the north wall of the tower was not found but may have been central creating a slight chicane. The outer edge of the barbican was placed in line with the lip of the ditch and here a smooth-faced stone revetment lay against the north wall at an angle of 45 degrees. This chamfered plinth or talus acted as a buttress, echoing the slope of the ditch. The ditch was 21ft wide here (18ft on the south side of the enclosure) and 4ft 6ins deep with an inner slope steeper than the outer one.

An oval-shaped stone-lined pit was found on the berm to the west of the barbican. Its sloping sides and northern entry point suggest that this was a limekiln, as found at the nearby Roman forts of Castlecary and Westerwood in post-Roman contexts. The lack of any evident signs of burning at Castle Rankine suggested to the excavators that it could not have been such a structure, but this may have been due to the low temperatures achieved. The walls of the barbican and curtain retained traces of lime mortar and the former would have required large quantities.

Few pottery sherds were found during the excavation at Castle Rankine, but this is not unusual and the recent excavations at Torwood Castle also found pottery scarce. That at Castle Rankine dated to the 14th-16th centuries. Animal bone was also found along with oyster shells. Oysters were plentiful in the Forth at this time and as well as providing food were often used as a source of calcium carbonate in the lime mortar.

This simple form of castle with a strong entrance tower and a plain walled enclosure surrounded by a defensive ditch was an early type and would suit a 13th century date. The curtain walls were not thick enough to take a wall walk and timber scaffold must have been used for that purpose.

During the Wars of Independence in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries Thomas de Morham and his son Herbert strongly opposed the English and for this the location of Castle Rankine was useful. It allowed the occupants to sally out and attack enemy forces passing though the area. In 1296 Thomas was captured and spent seventeen years in the Tower of London. Herbert then served in the English garrison at Edinburgh Castle and in 1299 met Johanna de Clare, the widowed Countess of Fife who was being kept by the English at Stirling Castle. He is alleged to have asked her to marry him. Shortly thereafter she left Stirling Castle for England under escort. What happened next can be made out from an order issued by Edward I of England:

“April 22, 1299.-The King commands his lieges, Patrick, Earl of Dunbar, and John de Kyngestone, constable of Edinburgh Castle, to inquire by a jury of Berwick, Roxburgh, and Edinburgh, into the charges brought by Johanna de Clare, Countess of Fife, against Herbert de Morham of Scotland, viz., that while she and her retinue under the King’s safe conduct were on their way to England, he laid wait for them between Stirling and Edinburgh, and took her by force to his brother Thomas’s house of Gertranky, where he imprisoned her because she would not consent to a marriage with him, under her oath to the King not to marry without his licence, and seized her jewels, horses, robes, and goods, to the value of 2,000 lib., to her grave loss and scandal, and in contempt of the King, who is greatly commoved thereat. They are to make the inquiry in presence of the accused persons, Herbert being brought under safe conduct from Edinburgh Castle to the trial, and taken back at its close. Westminster.”

Whilst superficially this incident may look like a case of robbery and ransom it may all have been contrived as part of the fight for independence. In any case, it is one of the few references to “Gertranky” or Castle Rankine.

The lack of references to Castle Rankine may be because the castle was abandoned as a stately residence at an early date. As will be seen in the list of proprietors the barony left the de Morhams through marriage in the 1330s, going first to the Giffords and then, also through marriage, to the Douglas family. By 1407 it was in the hands of the Sinclairs. All of these owners had extensive estates elsewhere and Castle Rankine was superfluous. It is pertinent that it is not depicted as a building of note on Pont’s map in the 1560s.

| 12th century | Adam de Morham |

| Thomas de Morham (son?) | |

| Herbert de Morham | |

| Herbert de Morham | |

| 1260s | Adam de Morham |

| Thomas de Morham | |

| c1296 | Thomas (brother Herbert beheaded 1307) |

| c1300 | Thomas de Morham |

| Thomas de Morham | |

| c1330 | Euphemia de Morham, married John Gifford |

| c1340 | Hugh Gifford (son) |

| c1350 | 4 daughters one of whom married John Douglas & inherited Herbertshire |

| 1369 | Archibald, Earl of Douglas |

| William Douglas (Ld Nithsdale) (son) | |

| 1407 | Giles Douglas (daughter) married Henry Sinclair, Earl of Orkney |

In 1413 Archibald, Earl of Douglas, granted a charter to his cousin, Malcolm Fleming, of the lands of Castlerankine and it stayed in that family (the Earls of Wigton) until the early 17th century when it was sold off into separate holdings. The Lands of Castle Rankine included Tongue, Harvies Mailling, Fisher Acre, Longfaulds, Wards, Bowrig, Parkhill, Rashiehill, Craigshield, Chamberfauld, Lamblinns, Leys, Brackenlees, Neutryhill, Maidenburn Ridge and Drumbowie with the privilege of Denny Muir and Berriemuir.

The castle was presumably used as a home farm before being allowed to fall into ruins. The Carron Company purchased Castlerankine in 1822 for the ironstone on the land and the farm was leased to tenants. In the 1850s there was still sufficient of the castle left for the Ordnance Surveyors to provide a correct square outline and to recognise that “This castellated building was, previous to its falling into disuse, a mansion of undoubted strength, and of an immense size. It apparently has lain a ruin for upwards of a century and all that now remains is a small portion of an inner wall which is preserved by the proprietors for the purpose of identifying the ground on which the ancient fortress stood” (Ordnance Survey Name Book).

In 1873 John Gillespie took up the lease of the farm and at the end of March that year fifteen farming neighbours turned out with their ploughs to give him a day’s darg, that is to say a day’s ploughing (Falkirk Herald 27 March 1873, 3). By then even the wall mentioned by the Ordnance Survey had gone, though the memory lingered a little longer. The Rev Thomas Miller’s mother spoke to him about it. This inculcated a curiosity for the site which led to Miller and a few of his friends to pay for the two week excavation in the summer of 1938. All of the digging was undertaken by John Campbell on his own. He had been the foreman on the archaeological excavation at Mumrills Roman fort. John Gillespie’s grandson got his workmen to do the backfilling.

Carron Company had assumed that it owned the coal as well as the ironstone on Castlerankine and it therefore came as a shock to it when James Wallace & Co from Glasgow started to sink shafts to work the coal in 1884. It turned out that in 1758 the Earl of Wigton had specifically reserved the coal for himself in a charter, and his successor gave the Glasgow firm the right to extract it (Glasgow Herald 8 Nov 1884, 7). The Castlerankine Pit continued to operate into the 1920s. During the Second World War a site just to the south-east of the farm was used as a detention centre for first generation Italians from central Scotland. Thereafter it was used as a prisoner of war camp for Italians captured during the North African campaigns, and then for German POWs. For a few years it accommodated displaced workers from Europe.

Today, as already stated, there is nothing to see of the castle. The route from Denny to Castlerankine Glen and back remains a favourite weekend walk for the townsfolk.

Sites and Monuments Records

| Castle Rankine | SMR 476 | NS 7857 8186 |

| Castle Rankine Limekiln | SMR 81 | NS 8850 8323 |

| Castlerankine Prisoner-of-war Camp | SMR 483 | NS 793 818 |

Bibliography

| RCAHMS | 1963 | Stirlingshire: An inventory of the ancient monuments. |

| Reid, J. | 1995 | ‘The feudal land divisions of Denny and Dunipace: Part 1’ Calatria 8, 21-39 |

| Smith, S | 1949 | ‘‘Castle Rankine,’ Proc Falkirk Archaeological & Natural History Soc, 4, 43-54. |

G.B. Bailey (2020)