The small tower house at Skaithmuir in the parish of Larbert was located 850m north-west of the harbour on the River Carron at Carronshore and only 600m south-west of Carronhall House. It was an enigmatic structure and one that has caused much debate. Some authors, such as W Maclaren were not even sure that it was an ancient building as it had clearly functioned as an engine house in the midst of a large coalfield. Others accepted its antiquity and derived different owners from the few sources. It is certainly a complex and muddled issue.

In the early medieval period the Lands of Kinnaird seem to have been very extensive and the feudal superior lived elsewhere. At an early date the lands of Quarrell and Skaithmuir were hived off and formed into the barony of Elphinstone. The western boundary of Skaithmuir was probably the Skaithmuir or Chapel Burn which marched with Stenhouse; whilst the eastern one was the Langdyke which leads north from Carronshore and also forms the boundary between the parishes of Larbert and Bothkennar. Skaithmuir too became divided with the westerly portion called simply “Skaithmuir” and the other “Easter Skaithmuir.” Skaithmuir was owned by the Mure family from at least the early 14th century until around 1643, though they did not own the superiority. Easter Skaithmuir was occupied by the Redhaughs and then the Bissetts, often in conjunction with Quarrell. What we know about these two lines can be roughly summarised as follows:

|

Skaithmuir |

Easter Skaithmuir | |||

| Pre 1329 | Reginald Mure | 1425 | Richard Redhaugh | |

| 1460s | Andrew Redhaugh (son) | |||

| 1466 | Christian Redhaugh (sister) | |||

| 1468 | Alexander Bissett (son) | |||

| 1482 | Alexander Mure | 1472 | Thomas Bissett (son) | |

| c1505 | William Mure (son) | c1510 | Thomas Bissett (son) | |

| 1533 | Robert Bissett (son) | |||

| 1544 | Robert Bissett (uncle) | |||

| c1565 | Alexander Mure | 1554 | Thomas Bissett (son) killed | |

| 1582 | Alexander Mure (son) | 1584 | Robert Bissett | |

| 1593 | Thomas Bissett (?) | |||

| Alexander Mure died c1643 | 1604 | Robert Bissett | ||

| Elphinstone family |

Various authors have attributed the construction of Skaithmuir Tower to Reginald Mure. The reason for this was probably the wording on a charter that he received in 1329 which described the area of land that he was receiving. The description of the bounds includes the phrase “and from that place ascending on the west to the corner of the eastern gable of the great hall which was newly erected by Reginald.” As is often the case, the size of the estate grew and diminished with the passing of time and it seems that he was adding a piece of land to the east of his existing holding. The mention of a great hall at so early a date is astonishing. However, we must remember that it is most likely to have been of timber. Nor, unfortunately, is its location known. The natural assumption would be that it corresponded with that of Skaithmuir Tower, but that need not be the case. It is noteworthy that the great hall stood on the very boundary of his original property. Both Roy in 1755 and Grassom in 1817 place Skaithmuir at what is now Roughlands Farm, and in this they were followed by the Ordnance Surveyors in 1862.

As early as 1549 the Elphinstone family held the superiority of Quarrell and Easter Skaithmuir whilst that of Skaithmuir was part of the barony of Straiton in East Lothian. John Bissett relinquished the estate of Easter Skaithmuir to his feudal superior in 1604. It was some years later, in 1636, that Michael Elphinstone took possession of Skaithmuir from Alexander Mure, uniting the two parts of Skaithmuir with Quarrell.

In 1610 James Elphinstone was designed as of Quarrell. He was the second son of Alexander, fourth Lord Elphinstone, and his wife Jean Livingstone, daughter of William, 6th Lord Livingstone. James resigned the lands of Quarrell and Easter Skaithmuir on 27 October 1619 to his father and they remained in the Elphinstone family until 1725. The reason for providing this particular detail is that Skaithmuir Tower had an inscription on a window lintel in the west gable inscribed, in raised letters and figures on a sunk panel, with the initials “L / A E,” for Alexander, 4th Lord Elphinstone, and “D / I LE,” for his wife Dame Jane Livingstone. Between the groups of initials the date 1607 is carved above a lozenge. This was the time when they first took possession of Easter Skaithmuir and therefore an appropriate time for them to have the tower constructed.

However, the possibility must also be entertained that the couple merely took over an existing residence and had their sign of ownership, in the form of the inscribed stone, inserted into it. It would not be the first time that a datestone has misled historians into thinking that a building started later than it did. Support for this comes from Timothy Pont’s map which clearly shows a modest tower house at “Skemure.” Pont’s maps date from the 1580s to about 1595 and by 1602 he was minister of Dunnett in Caithness. On balance it would seem that Skaithmuir Tower was built in the mid 16th century for one of the Bissett family.

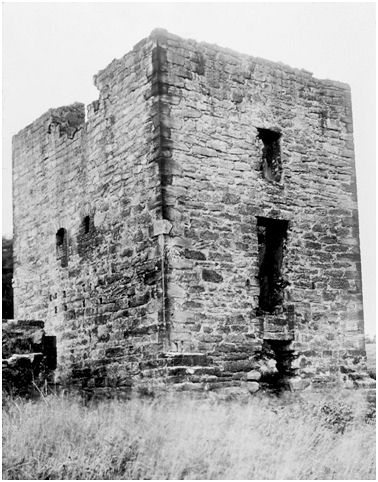

The tower was built of squared and irregularly coursed rubble, and measured 34ft 6in from east to west by 25ft 3in, over walls averaging 3ft 6in in thickness. It comprised three stories and an attic. The basement or cellar was vaulted and access was gained through the middle of the east gable by a doorway. Due to later alterations it is not known if there were any slit windows at this level. On the first floor was the hall which was also entered from the east by a door, immediately over the one to the basement. This must have been reached by a forestair. In the west gable there was a fireplace and a window.

There was no sign of any stair leading to the upper rooms and this must have been an internal wooden one. The second floor had fireplaces in the two northern corners suggesting that it was divided into at least two apartments. Sleeping accommodation usually occupied the upper storeys. Two squat lintelled windows were placed in the north wall with a larger one in the middle of each gable. The attic floor was lit by two small windows, probably dormers, about 3ft apart in the centre of the north wall.

There were probably two corresponding windows directly opposite in the south wall, but of these only the lowermost courses of the outer jambs survived in a broken-down gap in the wall-head when it was surveyed by the RCAHMS in 1953. There would have been no parapet at the wallheads and the plain ridged roof would have extended over them.

Along the outside of the south wall there was a splayed plinth indicating some degree of architectural embellishment on the main facade. Further decoration was provided by angle sundials set in the two corners of this frontage at approximately the level of the inscribed lintel.

In 1608 eight acres of the lands of Quarell and Skaithmuir were transferred from John Livingstone of Dunipace to Alexander, Lord Elphinstone (RMS vi 2192). This is roughly the same size of area that Fleming noted surrounding the tower as being enclosed by a demesne wall, 8ft high. This would have held the stables, gardens and orchard. It can be identified as enclosures numbered 294, 305, 306 and 304 on the first edition OS map. This places the tower at the east end of the park or policy, just as depicted by Pont.

Skaithmuir Tower was a neat, unfussy and compact dwelling. Whilst it was appropriate for the occupiers of Easter Skaithmuir it was not so for the owners of the Barony of Elphinstone. It does not seem to have been occupied for long after the Elphinstones took possession and shortly afterwards a new house was erected at Quarrell.

Quarrell and Skaithmuir were sold to John Drummond in 1725 and in 1749 they were bought by Thomas Dundas, a merchant in Edinburgh. Upon taking possession he renamed the house Carron Hall. He was quick to carry out agricultural improvements and to exploit the mineral wealth of the coalfield.

In 1760 the empty tower was used by Thomas Dundas to house a Newcomen steam engine (NSA) for the Quarrole Pit and a shaft was placed just 6ft to the south of it. This “fire engine” was used to pump water out of the pit and there were only just under 20 operating in Scotland at the time (see Duckham 1970, 83; an earlier one at Dunmore dated to 1719). Thomas Dundas also owned much of the colliery’s workforce who were still classified as serfs. Adam Smith and Mr Wright were in charge of the steam engine in 1760. In that year the colliery employed 31 miners as well as the two enginemen, two gate keepers, wagon fillers and drawers. Some of the coal was sold locally, known as “land sale,” but much was taken down to the harbour at Carronshore for sea sale. Carron Company took over the lease of the colliery in August 1760 to feed its furnaces. Adam Smith was retained and helped to erect another steam engine at the developing adjacent Kinnaird Colliery, eventually going to Kronstadt in Russia to assist in the assembly of the engine made at Carron.

Steam engines were rather expensive, but the cost of installing such machinery could be alleviated if an upstanding structure could be utilised to house the working parts. At Skaithmuir Tower the most noticeable alteration was the insertion of a large arched opening, 14ft 7ins wide, in the centre of the north wall, with its sill dropped below the first-floor level. The stone vaulting was removed and a central rubble platform in the former basement provided the seating for a furnace and boiler. The large entrance arch made access easier as well as providing a suitable updraft. Presumably coal would be stored to either side of the furnace. Above this would have been the cylinder, with the piston rod extending upwards from it, attached by a chain to one end of a large beam. The centre of the beam rested on pivots housed in the enlarged window openings in the south wall at third floor level. The other end of the beam extended out from the building and hovered above the shaft previously mentioned. A chain of rods connected this end of the beam to the shaft and the upwards and downwards motion of the beam created the necessary vacuum to raise water out of the pit. Two segmentally-arched openings, 2ft 8ins wide, immediately above the level of the crown voussoirs of the large arch provided ventilation and were matched by a similar pair in the south wall. The floor levels were changed to provide access to the machinery for its operation and maintenance.

Before long single storey extensions were added to either side of the engine house (after demolition the stumps of their walls gave some visitors the impression of buttresses for the tower). The 1862 Ordnance Survey map gives a good impression of this busy scene of industry. By then the old engine house had been replaced by a smaller structure to the south-east. The old tower house was incorporated into a large complex and lay to the east of a mineral line and its shunting yard. Along the main road miners’ cottages had sprung up and these were now called “Carronhall.”

By the time that the 2nd edition OS map was produced in 1897 the coal pit is marked as an “old shaft” and almost all of the colliery buildings, with the exception of the old tower, had been demolished. The tower was presumably left standing out of a respect for its antiquity.

Fleming in 1902 saw the old tower not long after the demolition of the colliery buildings

“The neglected condition and abuse of this medieval baron’s residence is regrettable, and raises a painful feeling that such a disregard for these historical memorials of a long-past generation should exist…”

The site appears to have been abandoned and

“all now open to and used by the population of the adjoining miners’ village for their rubbish” (ibid).

Council houses were built to the south in the 1930s and the area around the tower became a playground for children. The photograph shows it around 1940 as overgrown wasteland with the ruins of the colliery surrounding the tower house. The stepped chimney of the later engine house can be seen on the right. The tower was referred to locally as the “auld inginhoose” or the “dungeons”. As more and more council housing was built the area adjacent to the tower was improved, but it was only in 1974 that Central Regional Council solved the problem of the dangerous building by demolishing it. Today the area is part of a grassed park and there is no trace of the tower’s former existence. No attempt seems to have been made to save the lintel or sundials.

Sites and Monuments Records

| Skaithmuir Tower | SMR 649 | NS 8884 8348 |

| Skaithmuir Mill | SMR 655 | NS 8850 8323 |

Bibliography

| Duckham, B.F | 1970 | A History of the Scottish Coal Industry, Volume 1L 1700-1815. |

| Fleming, J.S. | 1902 | Ancient Castles and Mansions of the Stirling Nobility. |

| Maclaren, W.B. | 1949 | ‘Skaithmuir,’ Proc Falkirk Archaeological & Natural History Soc, 4, 57-65. |

| NSA | 1953 | New Statistical Account |

| RCAHMS | 1963 | Stirlingshire: An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments |

| Reid, J. | 2007 | ‘The Feudal Land Divisions of East Stirlingshire: the Lands and Baronies of Larbert,’ Calatria 24, 1-36. |

| Watters, B. | 2010 | Carron; where Iron runs like Water |

G.B. Bailey (2020)