A Battle Won – and Lost

The immediate vicinity of Stenhouse may be regarded as one of several Iron Age tribal centres located in the Falkirk district. Unfortunately the evidence for this was found at dispersed sites during the industrial development of Carron in the 19th century and was either ignored or misunderstood and was poorly recorded. During sand extraction by Carron Company at Goshen in 1882 a cist burial measuring 1.12m by 0.36-0.42m was encountered (SMR 112). It was constructed of rough stones with three large stone slabs forming the roof and contained an inhumation with a copper alloy brooch and an iron spear (see Bailey 1996, 27).

The skull mouldered away on exposure to the atmosphere but the brooch and spearhead were kept for some time in the Carron Company’s “museum.” The brooch (SMR 1428) was a typical Romano-British trumpet brooch of the late 1st-2nd century AD (Hunter 2001, 117) and it is reasonable to conclude that the occupant was a man of local importance. Another account says that a bronze spearhead was found nearby and was described as being “ornamented up the edges with brass studs sunk in flush with the surface of the surrounding metal.” Cowie has pointed out that this is unlikely to have belonged to the Bronze Age (Cowie 2001, 97). Ceremonial spears are, however, known in the Roman army (such as the silver spearhead from Caerleon – Boon 1972, 67) and were used as the upper part of the vexillum, a flag for a legionary detachment, as depicted on Trajan’s Column.

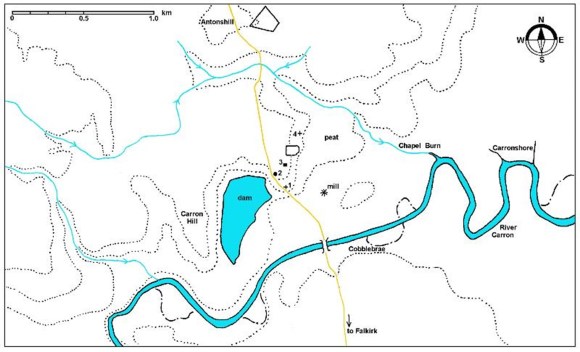

It is also possible that the two iron tyres found in the mossy ground near the present Carron Recreation Centre in 1800 were part of a chariot burial. Such tyres, along with lynch pins and terret rings, are all that usually survives the centuries. The tyres were discovered along with three or four mill stones during the digging of drains in that peaty area and were reported by Rev. Bonar. The mill stones were of the type of lava found in Andernach in Germany and commonly used by the Roman army on campaign. Bonar pointed out that this was the same type of stone as was used in a Roman burial just outside the south gate of the Antonine Wall fort at Mumrills.

These finds hint at the presence of a native elite in the vicinity. Tangible signs of such localised leaders are also found in neighbouring lands:

- Hill of Airth – chariot fittings in the form of three terret rings (one enamelled) and a lynch pin, as well as a trumpet brooch and tankard (SMR 2176). Nearby an enamelled brooch (SMR 2198) and lead weight.

- Torwood Broch (SMR 768) may have been occupied at this time.

- Dunipace – a later brooch from the 9th century? (SMR 752).

- Denny – a copper cauldron and three-legged pot may belong to this or to the medieval period. However a headstud brooch from Doghillock is Roman (SMR 1132).

- Cowden Hill, Bonnybridge – trumpet brooch, spiral rings and melon beads (SMR 747).

- Camelon – soldiers burials at Dorrator included spears, shields, etc, (SMR 138) and a multivallate enclosure containing a large roundhouse (SMR 147).

- Falkirk – the coin hoard found at Wormit Hill (SMR 560) included over a thousand silver coins dating up to the third century.

- Blackness – a cist burial with a brooch (SMR 103) at the later castle.

- Binns – another cist burial and brooch.

The Goshen cist burial was roughly 700m to the south-east of Arthur’s Oven and the putative “chariot” burial 1,000ft to its north-east. We therefore have to ask ourselves if the presence of a native leader in this area was partly responsible for the construction of that Roman edifice and if their continued presence led to its preservation after the Roman departure.

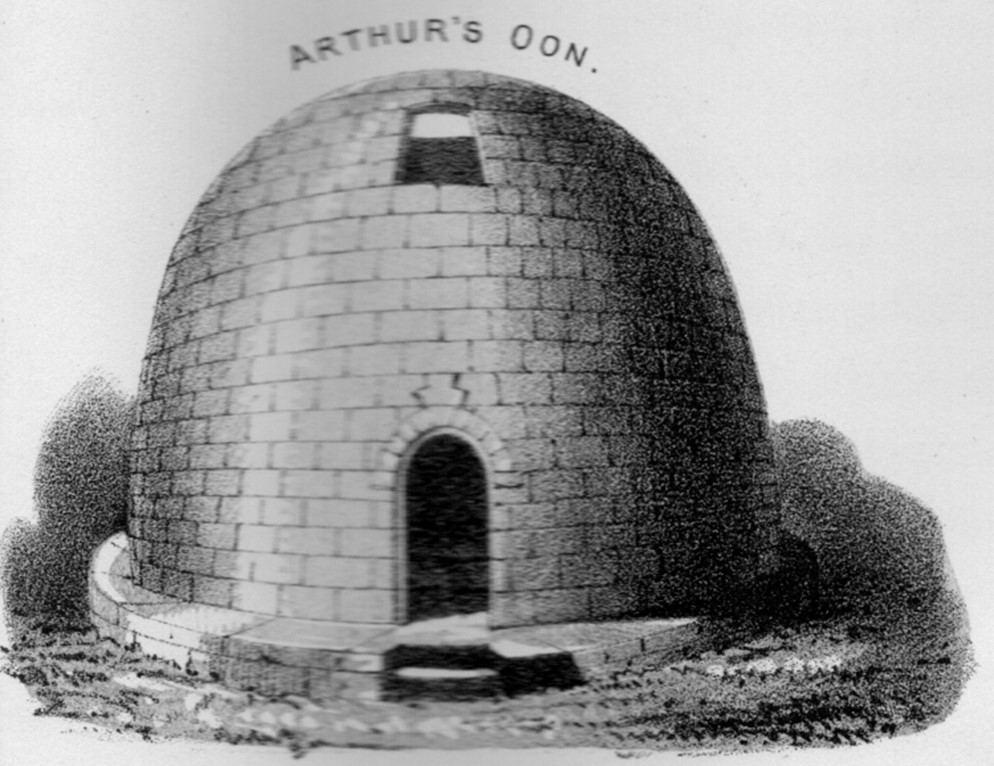

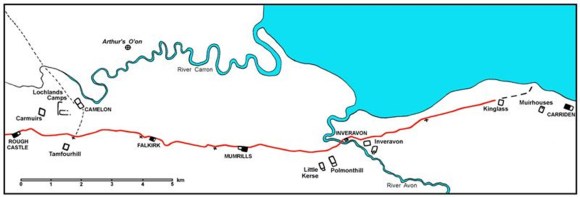

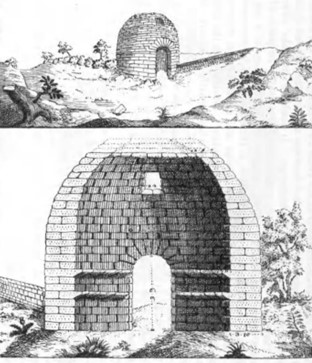

The monument, now known as Arthur’s Oven (SMR 388), was undoubtedly a temple built by the Roman army for a specific reason – the most probable being to commemorate a major triumph. It is not known in which of the Roman incursions into this part of Scotland it was constructed. It is unlikely that it belongs to any of the more fleeting visits in the early third or fourth centuries as none of them were consolidated into a lasting occupation. The best known of these under Severus appears to have been based on coastal forces and included forts at Cramond and Carpow, but none in the Falkirk area. The temporary camp at Househill (SMR 328) has been attributed to this period but without definite proof. This still leaves the Flavian period in the late 70s or early 80s AD, and the Antonine period when the Antonine Wall was occupied around 142-165AD to consider.

The fort at Camelon (SMR 1, 611-3) was occupied in the Flavian period. It occupied an important strategic location forming a bridgehead on the River Carron with a major road heading north to the installations on the Gask Ridge (see, for example, Woolliscroft & Hoffman 2006). The river was certainly navigable at least as far as Arthur’s Oven and possibly as far as the Camelon fort (Bailey 1992). Tacitus hints that a chain of forts was established across the isthmus around 81AD:

“The fourth season was spent in securing the districts already overrun; and if the valour of our army and the glory of Rome had permitted such a thing, a good place for halting the advance was found in Britain itself. The Clyde and the Forth, carried inland to a great depth on the tides of opposite seas, are separated only by a narrow neck of land. This isthmus was now firmly held by garrisons, and the whole expanse of country to the south was safely in our hands. The enemy had been pushed into what was virtually another island.” (Tacitus 23).

Camelon has been seen as one of these garrisons forming a temporary frontier anticipating the Antonine Wall. Other sites of this period were hypothesised at some of the later Antonine Wall sites such as Mumrills but this has been shown not to have been the case. Maxwell has suggested that the line may in fact have been further north including the fort at Doune. Never the less, Camelon was a vital node in the road network and the number of temporary camps in the immediate vicinity demonstrates that it was an assembly point for the Roman army on campaign. Many of these camps are later than the Flavian period. Agricola’s northern campaigns were marked by the joint use of land and sea forces. The latter were able to travel long distances and their arrival clearly surprised and terrorised the native populations.

Agricola’s major success came three years after the temporary halt at the Forth-Clyde isthmus with a decisive victory at Mons Graupius at which, incidentally, Caledonian war chariots are mentioned. Agricola was granted a triumphal acclamation in Rome, together with a statue there, and then summoned home. Tacitus makes no mention of any monument or acclamation in Britain. On the contrary, he suggests that Agricola deliberately acted with circumspection and that shortly afterwards the conquests were relinquished by a zealous emperor. However, this may have been a contrivance, used to illustrate his theme regarding the mistreatment of Agricola by Domitian, and it would have suited Tacitus to omit any mention of a triumphal monument in Scotland. The chance that Arthur’s oven represents a celebration of the battle of Mons Graupius is tantalising! Such a temple need not have been constructed at the battlefield itself and a site nearer the “good place for halting the advance” is a possibility, especially one with a prominent situation overlooking the Forth that would link to the maritime use of force.

In another of his accounts Tacitus says “Britain was completely conquered and then immediately forgotten about” (Histories, I, 2). The wording is interesting. The word “omissa” (forgotten) implies a process of neglect and not abrupt abandonment. A recent analysis of the coins from Camelon has suggested that it continued in occupation from around 80 AD to c110 AD (Brickstock 2020), well beyond Agricola’s time in Scotland. It is in this extended period, when the site stood in relative isolation, that a victory may have been hard won nearby and commemorated by a monument such as Arthur’s Oven. Camelon is only 2.3km to the south-west of the monument. We have good reason to believe that a senior officer in the Roman army died in the area and that his remains were buried at Camelon. An Egyptian travertine urn found during the cutting of the Polmont Junction Railway in 1849 in this area is a rare and exotic item signifying a high status individual.

It contained calcined bones and was originally identified as alabaster (Hunter 2020). Unfortunately, both the context of the discovery and the bones have been lost, and it is not now possible to say whether it belonged to the Flavian or Antonine occupation.

The Flavian occupation of central Scotland enhanced the Roman’s knowledge of this part of the world and it is generally accepted that it was information gained at this time that was incorporated into Ptolemy’s “Geography” around 140-150AD. This provided a list of the tribes who occupied Scotland at the time along with a list of place names attributed to each together with their map-coordinates. The coordinates suffer from the fact that the whole of Scotland north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus was turned perpendicularly to the east, perhaps because the Greeks believed that life was not possible beyond the latitude of 63 degrees north. In this process the coordinates had to be “corrected” to make them fit and the resultant relative errors are at their most extreme at the hinge point of the isthmus. Included in the list is a place called “Victoria” in the land of the Dumnonii (Ptolemy II, 3, 7). This tribal group appears to have extended across Ayrshire into southern Perthshire and so included the Falkirk area. The evocative place name is of considerable interest as at first glance it would seem to commemorate a major victory such as that achieved at Mons Graupius. An influential study of the place names of Roman Britain equated Victoria with the legionary fortress at Inchtuthil in Perthshire occupied by the Legio XX Victrix because of the legion’s title (Rivet & Smith 1979, 499). However, Frere pointed out that this is highly improbable since the adjective from Victrix would be Victricensis and not Victoria (Frere 1980, 421). The most likely name for Inchtuthil in Ptolemy’s list is Pinnata Castra which translates as “the fortress with stone merlons (crenellated walls).” This is one of only six sites in Britain for which Ptolemy gives a measurement of the longest day of the year, strongly indicating that Pinnata Castra was a legionary fortress (Maxwell 1990, 117). The coordinates provided by Ptolemy for it place it further north that its true location and this may be the same for Victoria which is placed between the Forth and Tay. A similar adjustment would put Victoria in the Falkirk area and more convincingly into the tribal area of the Dumnonii.

The fort at Camelon was reoccupied during the Antonine period and so its physical relationship with Arthur’s Oven was much the same as in the Flavian period, though the context had radically changed. Arthur’s Oven lies 1.1km to the north of the Antonine Wall and according to Gordon, writing in 1726, was visible from Kinneil. Today it is possible to make out the cooling towers at Grangemouth from Castlehill which is the highest point on the Wall besides Bar Hill and it should have been possible to have seen Arthur’s Oven from there on a clear day. A study of the contours indicates that this was so. The temple sat at around 75ft OD on a small hill a little to the south-west of the site of the early 17th century tower house of Stenhouse which also enjoyed extensive views. To the east were the low-lying carselands through which the River Carron winds its slow passage. It has been postulated that Camelon was the main supply base for the eastern end of the Antonine Wall (Tatton-Brown 1980) and the greater range of pottery and other material at the fort when compared to the Wall forts would seem to reinforce this idea. Arthur’s oven was not, however, a lighthouse. During daylight it may have acted as a navigation beacon. In the mid 18th century ships of 60 tons burden regularly sailed to Carronshore from London and a vessel of that size was even built near to Stenhouse Dam (Bailey 1992). That dam, and another just upstream from it, interrupted the natural water movements and reduced the tidal limit of the river. With a winding river the tide would have been a useful ally for inward bound ships. Fortunately, these meanders are significantly reduced in scale to the west of Carron and with a copious supply of water issuing from its catchment area there is no reason why the river should not have been navigable as far as the fort. It is noticeable that the fort stood next to a convex bend in the river some distance from the bridging point. The river has since been straightened to increase the size of the ships cable of reaching Carronshore to 120 tons and to reclaim land. A broad strip of land was also reclaimed from the Forth, but not nearly as much as some commentators have indicated. The map below shows the probable Roman coastline.

It has been suggested that construction of the turf barrier of the Antonine Wall began on the high ground at Watling Lodge to the south of Camelon and proceeded westwards. It was later extended to the east using earth retained by clay-rich cheeks. Watling Lodge has extensive views to the east and west and Arthur’s Oven would have been clearly visible from it. By coincidence a domed temple similar to Arthur’s Oven has been suggested to the north of Hadrian’s Wall at Gilsland towards the west end of the original stone section of that mural barrier. The evidence comes from a sculptured stone showing Victory found prior to 1807 in the ditch surrounding a sugar-loaf shaped hill called Rosehill. (Breeze 2014, 59). It is rectangular in shape, its front face measuring 0.58 by 1.10m, and appears to be one stone from a larger tableau – a frieze over 3m long. This stone clearly occupied the right-hand edge, framed by a fluted column with a Corinthian capital and moulded base. The adjacent stone to the left presumably carried the laurel wreath which Victory held in her right hand. It is also possible, though unlikely, that a stone laid on top of it showed the triangular pediment of a temple supported by the column on right and a matching one on the missing stone to the left. Such a pediment is shown on the single stone from the Antonine Wall at Old Kilpatrick (RIB 2208), which is stylistically similar both in its depiction of Victory and especially in the manner of executing the column.

On the Rosehill Stone Victory is shown flying to the left with her right arm extended. Her hair is gathered in a bun (“piled up”) on the back of her head. She is naked down to the thighs with high breasts and a slender waist and prominent navel. From here flimsy “transparent” drapery extends down to just above her ankles. The body is twisted with the torso frontal on but her legs sideways. Unfortunately it is difficult to say if the head also faces the front or to the left (as depicted by Fairholt in the mid 19th century woodcut of this stone). This makes it uncertain if her right arm was ever illustrated or, like her contortionist legs, was meant to be seen in the profile of her right arm. As only one wing is depicted this seems highly probable.

Below and to the left of Victory is a bird with outstretched wings which must have been an eagle. Its head is now missing and Coulston and Phillips (1988, 105) assumed that it faced the spectator. It could equally have faced to the left, focussing attention on the centre of the composition as does a similar eagle on the Summerston Stone from the Antonine Wall (RIB 2193). The association of Victory and an eagle is common on Roman military sculpture. Here the bird is standing on a round-topped feature which could be a globe – also a common association. To the right of Victory and pressed right up against the margin of the scene is a domed building with a central recessed flat-topped doorway (actually it is just to the right of centre). Behind it a tree emerges and bifurcates to support a leafy canopy. In front of the building, partly obscuring it, is a disfigured area carved in relief, often described as a rocky hillock – which it clearly was not. Straight lines and structure can be made out in this mass indicating that is was more than a rock. The composition appears to be carefully set out and the placement of the domed building so close to the column and the slight lateral displacement of the doorway was intended to draw attention to it. It is now generally accepted that the building represents a temple and so the “rocky” relief in front of it may have been connected with its rituals – such as a sacrifice at an external altar. The presence of Victory and the eagle would also allow it to be a tropaeum (trophy) – a monument erected to commemorate a victory over the enemy on which the armour of the defeated foe was hung. Originally the location of the trophy was the battlefield where the commemorated victory took place. Traditionally it was constructed out of a living tree with lateral branches. By the Antonine period this type of monument might take the form of spears or javelins set crosswise with the armour mounted on a sturdy central stake with swords and shields below.

Richmond seems to have been the first to point out the similarity of the building depicted on the Rosehill Stone to Arthur’s Oven (Breeze 2014, 60). Coulston and Phillips (1988) took this a step further and suggested that it might actually depict that monument, though they admitted the possibility of a similar temple of Victory at Rosehill, which is favoured by Breeze. However, the stone is the only evidence for such a structure and the artificial hill and ditch have also been identified as a medieval motte. In either case the symbolism on the stone is important because the forked tree behind the temple might be seen as an indication that the temple structure was erected remote from the battlefield.

The Antonine invasion of Scotland certainly provides an alternative occasion when a temple of Victory might have been erected at Stenhouse. The invasion was one of the first acts of the reign of Antoninus Pius and, although it might have been a reaction to trouble in northern Britain, the advancement of the frontier appears to have been politically motivated. The new emperor needed a military triumph to secure his reign and the timing was apposite. It is noteworthy that this was the only occasion upon which he took the title of “Imperator” – Conqueror – despite successful military operations elsewhere later in his reign. It is also noteworthy that the aims of the campaign were clearly established and limited to the advancement of the frontier rather than the conquest of the whole island. Hadrian’s Wall was already famous and replacing it would have been seen as a noteworthy achievement. In this scenario it is possible that a battle took place in the vicinity with the Forth-Clyde line being seen by the native forces as a defining one. A parallel may be drawn with the accession of Claudius who responded to his precarious position with the invasion of Britain. Subsequently a massive triumphal arch was raised at Richburgh, one of the invasion points.

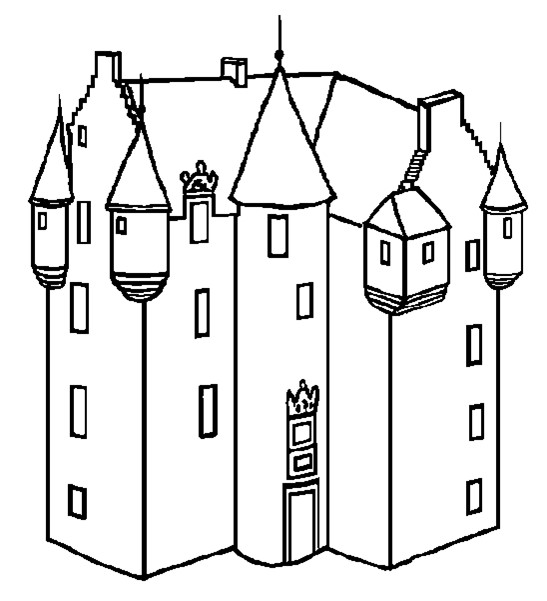

Prior to 1830 the main road north from the ford and then the bridge at Carron passed immediately to the west of Stenhouse Castle (see below). From here, a little to the north of the site of Arthur’s Oven, a public road known as the Broom Loan led to Stenhousemuir and in 1863 it was noted that:

“according to my veteran friend, over 30 years since the Broom Lone was dug up, and he who was contractor reports that the workmen, while excavating, came upon many gravestones which had been erected, centuries before, in memory of those who had died of the plague” (Stirling Observer, 5 March 1863, 6).

This latter was supposition and probably came about by a misplaced association with the Plague Stone of James Heugh – a standing stone which stood further to the west (see Family Graveyards). It would be unusual to have a large number of individual stones for plague victims. Had the stones been inscribed this would surely have been noted and so we must consider the possibility that they were Roman and therefore associated with Arthur’s Oven.

A second standing stone, known as “Ossian’s Stone,” (SMR 2191) was situated a little way to the north of the stables at Stenhouse (NS 8782 8304) and, according to late tradition, Ossian was buried in that spot. In 1859 it was described as

“a relic revered by the antiquary” and “the only object of note on the estate” (Falkirk Herald 29 December 1859).

Unfortunately there is no physical description of the stone which is no longer extant and would have stood approximately 150m north of Arthur’s Oven. Is it possible that it too was associated with that temple?

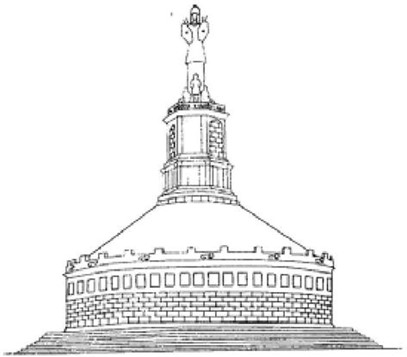

The Tropaeum Traiani at Adamclisi was built in 109 AD to commemorate Trajan’s victory over the Dacians in the winter of 101-102 which culminated in a large battle. It is therefore closer in date to Arthur’s Oven. The Adamclisi monument is located on the highest hill in the area. The main monument took the form of a circular mausoleum – a cylindrical drum set on seven steps and capped by a conical top supporting a trophy. It was dedicated to Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger). On its exterior walls were 54 metopes – rectangular slabs with a height of 1.48–1.49 m carrying bas reliefs. Of the 54 metopes, 48 are still preserved. A group of metopes represents Trajan; another group has Roman soldiers on the march; most of them depict battle scenes against the Dacians. In many scenes wounded and dead are seen amongst the Dacians and their allies. A special two-piece group shows a legionary piercing a man with a spear, whilst a woman stands with her arms outstretched and a child runs around the chariot. The final group of metopes portrays the last battles and the Roman victory with the taking of male and female prisoners. The monument was supposed to be a warning to the tribes outside this newly conquered province. A large altar stood 200m to the east of this monument and some 3,800 names of the soldiers who died in battle were inscribed upon it. About 50m north of the main monument is an earthen mound covered by a circular mausoleum (40m in diameter), probably the tomb of the commander killed in battle and listed first on the altar. It is often said that the Tropaeum Traiani was built adjacent to the Battle of Adamclisi but there is no evidence for this and it seems to be some distance from the main theatre of action.

For comparisons we should look at two of the well-known trophies of the Roman world, the Tropaeum Augusti (or Trophée des Alpes) and Tropaeum Traiani, located in France and Romania respectively. Both have round structures as their main element – though on far grander scales than that at Arthur’s Oven and in more classical styles. The Tropaeum Augusti was built for the emperor Augustus in 7/6 BC to commemorate the Alpine military campaign in which Drusus and Tiberius conquered a total of 46 tribes, as recorded by Pliny the Elder. It stands on a prominent hill overlooking the Mediterranean and distant from the battles that it commemorates. On a massive square podium sat a Doric temple with 24 columns placed on the circumference. The frieze above these contained sculpted metopes between triglyphs. The limestone metopes were adorned with various motifs such as armour, the bow of a ship, and the head of cattle. The dome capping the structure narrowed up in steps and was crowned by a colossal statue of Augustus. The dedicatory inscription on the plinth was flanked by two Victories and captured weapons in the form of a trophy hung from a tree trunk.

The quality of the masonry at Arthur’s Oven places it in the upper bracket of structures in Roman Britain. The exterior was said to have had a polished finish and the joints were tight, leading some antiquarians to believe that mortar had not been used. The stones were large and were lifted into position by a crane using Lewis holes. This was evidently an imperial project of considerable prestige and, although smaller, fits in well with the two tropaeia just described.

Ibarra has discussed the symbolism of tropaeia and their locations, noting that

“The locations were often boundaries, luminal areas between one province and another, land and sea, life and death. The trophy commemorated victory, memorialized fallen soldiers, and honoured the gods. Once built, the trophy was inviolable regardless of its patron” (Ibarra 138).

Such a setting could be ascribed to Arthur’s Oven.

The antiquarian descriptions of Arthur’s Oven agree that the interior was once richly decorated with carvings, though these had been deliberately defaced and the poor light inside the building made them difficult to discern. Gordon, writing in 1726, was aware of the deterioration in the images:

“a Bass-Relieve cut upon a Stone above the Arch of the Door on the Inside, upon which have been engraven the Roman Insignia or Vexilla, and an Eagle with expanded Wings in the Middle. I confess, Age and Time, and perhaps the same barbarous Hand that erased the Letters, may have defaced them also; but David Buchanan remarks, that the Eagle and Insignia were to be seen pretty plain in his Time; and, in his Manuscript Notes preserved at Edinburgh, he describes the Bass Relievo, and calls the Eagle the Roman Earn, which, in the old Scotch Language, signifies Eagle; and even now part of the Body, and one of the Wings, may be faintly discerned.”

Thirty years earlier Sibbald had visited the building several times and explored it minutely, recognising different features on each occasion:

“Within the oven above the door there are like 3 eagles… When I was last there I saw in the inner north east side a spear high from the ground some characters which I could not distinctly read but I conjecture it may be the measure of the length of the wall for there was not so many Legions in the Island as the numbers seem to amount to… A torch lighted and a Ladder might make you read them, at least take them off just as they stand” (Sibbald 1699).

“I had occasion to see this Roman Monument several times, the last time I was in that Countrey, I viewed it narrowly with a lighted Link… I remarked with the Light some strocks graven, which look like the razing and deleting of some Letters, this is to be the North-east of the Door high up within a Yard and a half of the top of the Building, upon the South of the Door, high up I discerned the Figure of an Eagles Head, somewhat worn out by time, and upon the same side I saw a Figure much worn out, or partly deleted, which resembles Wings, and seems to have been the Figure of Victory; near to it was a Figure like to the head of a Spear or Javeline, with a piece of the Handle of it, below it was these Letters, I.A.M.P.M.P.T. these I cannot understand…” (Sibbald 1707).

Sibbald recorded other finds from the vicinity :

“my Friend the Reverend Mr Woodraw, hath a Piece of a Patera, such as was used in Sacrifices, that was found near to it. There is in the Common Hall of the College of Edinburgh, amongst the Curiosities collected by Sir Andrew Balfour, the Interior part of the Horns of a Bull of a great Bulk, which was digged out of the ground near to this Monument, called Aedes Termini; so it seems there have been sacrifices there” (Sibbald 1707).

One of the major ceremonies involving the sacrifice of a bull at an altar was the suovetaurilia, as depicted upon the Bridgeness tablet where the scene takes place in front of a temple with a triangular pediment.

Lettering, eagles and winged Victories feature in most of the accounts and are consistent with a tropaeum. All of the records except Gordon indicate that the structure faced east (Roy’s account is based upon Gordon and also shows the door on the west) which is normal for Roman temples. It was in the precinct in front of the door that external ceremonies took place and where an altar would have been placed. The remnant of a possible altar was found re-used in the construction of a 16th century pottery kiln to the north-east of Arthur’s Oven in 2007 (Hall 2009)

A conspicuous feature of the Tropaeum Augusti and the Tropaeum Traiani were the bas relief metopes depicting military themes. Compositionally those in Romania are not dissimilar to the scenes on Trajan’s Column in Rome and are stylistically like the figured carvings on the distance tablets from the Antonine Wall. These latter depict Victories, wreaths, eagles, Mars the Avenger, the souvetaurilia and captives as well as vexilla and legionary emblems. The battle scene on the Bridgeness Tablet has a stylised temple façade in the background – is this convention or a tangential reference to a tropaeum? The distance tablets would be at home in a tropaeum though here they are spread over 38 miles. Perhaps the Antonine Wall, replacing Hadrian’s Wall, was the Triumph – the Tropaeum Antoninus! As such it would complement the earlier one at Stenhouse.

These distance tablets seem to have been deliberately removed from their plinths by the withdrawing Roman army and buried upside down in shallow pits nearby in order to stop them from falling into enemy hands. As sacred objects it would have been the intention to keep them from despoliation and as imperial propaganda it was better to deny them being used by the enemy as a symbol of Rome’s failure. It may have been during the final pull out that the Bridgeness Tablet was taken from a position near the eastern terminus of the Wall to a harbour at Bridgeness so that it could be safely retained at a new location on Hadrian’s Wall. In the end it too was abandoned and left face downwards. A voussoir stone, believed to have come from the dismantling of the bathhouse at Carriden, was found nearby. Such stones were probably transferred to the garrison’s new base for re-use (Bailey 2021, 194). Is it possible that the Rosehill Stone was moved southward at this time?

Whatever the function of the famous structure known as Arthur’s Oven was, it was left largely intact when the Roman army withdrew from Scotland. It is sometimes said that the Romans would not have wanted to demolish a structure which to them was sacred and this would have been doubly so if it represented not simply a tropaeum but also a memorial to the men who had helped it to achieve the military victory that had initially secured the area. The evidence from the Antonine Wall shows that they had no qualms about throwing altars down well shafts or burying the distance tablets. We must therefore assume that, at the very least, Arthur’s Oven was stripped of its portable contents by the army before the retrenchment to Hadrian’s Wall. A large bronze statue, presumably of an emperor, appears to have been smashed, leaving only a finger behind which somehow ended up being tucked into a crevice in the masonry. It is possible that the act of concealment was deliberate and symbolic. In the post-medieval period a large stone in the southern part of the interior was identified as the plinth for a sacrificial altar, but the altar itself had long gone, removed, tradition had it, by locals in the Christian era who abhorred the earlier religions. Of course it is also possible that this was merely the plinth for the statue. The significant sculptures embedded into the walls could not have been removed without taking the building apart.

It is a moot question as to why the indigenous population did not then destroy the structure once they had taken possession of it. Surely it would have been seen as a symbol of Roman dominion, art and culture. Whilst it took a great deal of effort to construct, it would not have been so difficult to tear it asunder. Yet it was appropriated by the local people, or at least by its leaders, presumably as a powerful sign of their eventual triumph over the Romans. In this respect it would have been almost as significant a symbol as the capture of a legionary eagle bestowing high honour on its possessor. Were the internal sculptures ritually defaced at this time or retained as reminders of what had taken place?

The building was extremely impressive and its possession would have given great kudos to its new owners. It was visible from a great distance and would still have projected power and influence over a large area. Its significance was such that it would have been used either as a sacred shrine or a great hall – a meeting place of peoples and a beacon for travellers.

There was evidently much post-Roman activity in the area but in an aceramic age this is difficult to detect. The Falkirk Hoard of around a thousand silver coins casts a shadowy reflection on the possibilities. It dates to the early third century and is now interpreted as a Roman bribe to the local warlord. Immediate post-Roman activity has also been suggested to the west of the fort at Falkirk (Bailey 2021, 470, 478) and slightly later in the immediate area (Bailey 2016). A ninth century silver pin from Dunipace is of high status. This society was hierarchical and status often depended upon symbols from the Roman occupation. It is easy to envisage the O’on or hall-like chamber with an open fire set in the centre of the stone-paved floor and the smoke ascending to escape through a hole at the top.

The location too remained significant, dominating the fords across the River Carron. These provided a route north, hugging the coast to Airth and Stirling, or inland along the old Roman road which runs through Torwood, crossing the muir at Stenhouse via what was later called the Broom Loan. To the east of the site a small stream fed into the river. Its valley turns to the west and the water course continues as far as the new hospital at Larbert. The stream is unusual in that it only possesses one name throughout its entire length – the Chapel Burn. It would be more usual for a stream of this length to have each section named after the community that it ran through such as Larbert, Broomage or Stenhouse. This suggests that the name was of early derivation, probably from a very prominent landmark. It has been postulated that the name comes from a late medieval chapel of St Anthony on Antonshill, but the evidence for such an establishment is tenuous (Nimmo 1880, 327). It is possible that it was named after the ancient structure of Arthur’s Oven which from an early period was referred to as a temple or chapel.

Gordon tells us that Arthur’s Oven could be seen from Kinneil on the coast 13 miles (21km) to the east-south-east. It stood out from the flat carse land bordering the Forth to the east. Likewise it was visible for a similar distance along the Antonine Wall to the west-south-west. Although not on a high contour, it was prominent. Etymologically the name “Arthur” is believed to derive from Ardnan or Ardhe signifying a higher Place. As Bonar pointed out in 1843 Ard and Arthur in Cymric or Welsh, comes from “the same root is Arduus, Latin, signify high, and also the Most High God.” Given the relatively low contour of the site it would seem that it was the monument’s elevated political status that was the significant factor in its name.

Carroll (1996) would have us believe that the building was associated with the high king, King Arthur, and there are many indications of a Scottish locus for this illustrious character. Could Arthur’s Oven have been the origin of the story of the round table? Boece in 1527 mentions stone benches “with benkis of stayn gangand rowynd abowte within,” though these were taken as being the two string-courses by later writers. Earlier still Fordun tells us that it had “an entrance so large that an armed soldier on horseback can pass in, without touching the top of the doorway with the crested helmet on his head.” This seems to be an echo of a knightly tradition. (The doorway was in fact only 9ft in height.) Round tables are known from early history, such as one associated with Charlemagne, and so had a long connection with royalty.

Edward I of England was a great believer in the chivalric tradition of King Arthur and it is not surprising to see his name associated with Arthur’s Oven. The “Winchester Round Table”, a large tabletop hanging in Winchester Castle has been dated by dendrochronology to his reign around 1280. It now bears the names of the knights of Arthur’s court, though this paintwork was added for Henry VIII. Edward I also attended several “round tables” which were international festivals that included joisting. Boece claims that Arthur’s Oven “was bett doun be Edward Langschankis quhen he ouraid mekle of Scotland.” Later on he clarified this by adding

“King Edward, he detroyit all the antiquities of Scotland, he commandit the round Tempil beside Camelon to be cassin down… the Inhabitants saiffit the same fra utter Eversioun putting the Roman Signes and subscriptions out of the Walls thereof, als they put away the Arms, and ingravit the Arms of King Arthure, commanding it to be callit Arthurs Hoisse.”

Evidently by the 16th century the internal sculptures had been defaced, but how much faith we can put in Boece’s attribution of their eradication to Edward I is debatable. Like many writers of Scottish history at the time there was a political dimension to his works. Edward I was certainly in the vicinity in the 1290s.

It is interesting that Boece associated Arthur’s Oven with Scottish national identity and consequently regarded Edward I’s action as part of his cultural campaign against the Scots. Being on a major route to the north and very conspicuous as a landmark for centuries it is easy to see how it might become a symbol of national pride as did the Tropaeum Augusta to the Royal House of Savoy (and later to that of France). However, the despoliation of the pagan images was probably from a much earlier period. It may have been the reaction of the local populace on the departure of the Romans, or the Christianising influences of the Church.

The crossing point of the River Carron for Edward’s army was at Dunipace (which is usually taken to have been beside the Hills of Dunipace, but may have been at Denny) and this seems to have been the preferred crossing point for armies before the construction of bridges. The river was a major obstacle to north/south travel and hence a suitable defensive line. The Jacobite army of 1746 crossed the river at the Hills of Dunipace, surprising the small guard on duty there. The nearby bridge at Larbert was more heavily protected by the Hanoverian army which subsequently used it in its northward progress against the Jacobites. Larbert Bridge was the centre of action in 1651 when the Royalist Scottish army blocked Cromwell’s advance along the river frontage. The fords lower down the river were also probed on that occasion but even the professional army of Cromwell found it easier to cross the Forth Estuary at Inverkeithing than to cross the Carron opposed.

It is tempting to think that the incident that occurred in August 1578 when the Lords’ Army marched out of Falkirk on its way to Stirling to “rescue” James VI from Regent Morton took place at Carron, but this is unlikely; tempting because that occasion witnessed an Arthurian style joust on the banks of the river.

“one Tait, a follower of Cesford, who as then was the Lords party, came forth in a bravery, and called to the opposite horsemen, asking if any among them had courage to break a lance for his Mistress. He was answered by one Johnston, servant to the Master of Glamis, and his challenge accepted. The place chosen was a little plain at the river of Carron, on both sides whereof the horsemen stood spectators. At the first encounter Tait, having his body pierced through, fell from his horse, and presently died. This was taken by those of Mortons side to be a presage of Victory” (Spottiswoode).

Tradition also has it that William Wallace and the Scottish troops crossed the river at Carron fleeing directly northwards from the victorious English after the Battle of Falkirk in July 1298. This route would have given them the quickest access to the protection afforded by the river. Sir John de Graham fell covering the rearguard and an English knight, Brian de Jay, is said to have been killed when his horse stuck in the mud besides the river crossing. Later historians erroneously connected this with the origin of the place name Bainsford. In 1293 the monks of Newbattle were given “the use of the mill which was of Stanhus and which lies nearby Arthur’s O’on within the barony of Dunypas.” This was a pre-existing mill demonstrating the existence of a community in the area. A little to the north-east of Arthur’s Oven a pottery was running in the early 15th century producing red ware (oxidised green-glazed ware) with markets in the burghs of Falkirk and Linlithgow. Some products were exported along the River Carron and down the east coast and the pottery became a relatively large-scale concern. The kilns were lined with stone and amongst these a dressed fragment of sandstone was found with two mouldings. Given its context it is not unreasonable to see this as part of the base of a Roman altar. The pottery utilised the local assets of peat for fuel, clay for the bodies and sand as a temper. The industry was there for over a century and in that time the amount of peat and clay consumed resulted in two large hollows – one to the east where the new recreation centre is now, and one well to the south which was later utilised for the reservoirs of the Carron Company in the mid 18th century (Carron Dams). The juxtaposition of corn mill, ancient temple, laird’s house and pottery industry would not have seemed out of place.

The Lands of Stenhouse came into the ownership of the Bruces of Airth in 1451 and these formed a separate cadet branch of the family in the early seventeenth century when Sir William Bruce was in possession. He was created the first Baronet in 1629. Undoubtedly there would have been a timber hall here in the medieval period, but it was only in 1622 that a sizeable L-shaped tower house was built for William Bruce on the east side of the flat summit of the hill. It is surprising that Arthur’s Oven was not quarried at this time as a readily available source of stone. That it was not may have been due to the long family connection with the structure. Various antiquarians note that a St George’s Cross in a shield was carved on one of the stones inside the building – the saltire was the emblem of the Bruce family. It is possible that it had been retained as a family mausoleum. An iron gate at the doorway also receives mention and sounds more like a late medieval yett than a Roman device. The gate would have been necessary as the building lay adjacent to the main road north to Airth which became known as the Oon Path. The gate was removed by the Monteiths of Kerse shortly before 1631. By then the Bruce Aisle had been added to Airth Church and bears the date 1614.

Stenhouse sat on the eastern edge of a large open muir which remained unimproved until the late 18th century. This is clearly shown on Roy’s map of 1755. Such moorland had an economic value, particularly for grazing cattle and for the extraction of peat.

By the early 17th century the pottery was on the wane. Over the following decades the grounds and gardens of Stenhouse were laid out. As fashions changed so too did the grounds and privacy and remoteness were sought.

Arthur’s Oven must have been maintained at this period as none of the more detailed antiquarian reports of the early 18th century mention seeing the stones on the floor from the collapsed central opening in the roof. This was a time of enlightenment when scholarship sought information from the structures of the past, and as part of this produced a written record. John Urry visited the site in 1697, John Adair around 1700, Robert Sibbald several times between 1690 and 1710, Edward Lhwyd in 1699, Alexander Johnston in 1712, Adams, Andrews Jelfe in 1719 and Alexander Gordon before 1726. Sir John Clerk of Penicuik must surely have visited during this period for he took a keen interest in the site. Their work and the publications thereon would have attracted further tourists seeking the antique at home.

They had great expansive views to the east across the Forth, but were hemmed in by the public road on the west. This road had been used for so long that it had turned into a hollow way and this that was depicted in Stukeley’s drawings. Although he never visited the site in person he based his illustration upon Jelfe’s on the spot sketches in a pocket book. It is hard to see why he would have made up the cluttered background – certainly it was not for aesthetic reasons. A depression is shown curving around the front of the building and is silhouetted against the skyline on both sides. It does not form an arc centred upon the building. The road from Airth approached Arthur’s Oven in more or less a north/south alignment and then curved around the building towards the south east. To the left of this the illustration depicts a hedgerow dotted with trees and to the right a stone dyke. If accurate this suggests that the entrance was indeed to the west as Gordon corrected and indicated on his plan. However, so many of the sources state that the entrance was on the east that this must be a misunderstanding of the notes. The road, this time with a horseman traversing it, also appears on the Stukeley’s 1757 version and here the entrance is to the east.

The monument had become internationally famous and a source of national pride, so Sir John Clerk was caught completely by surprise when in late 1742 it was deliberately demolished. On 22 June 1743 Clerk wrote:

“I believe you may have heard of a heavy shock that the antiquarians in the country have received by one Sir Michael Bruce, proprietor of the grounds about Arthur’s Oon; for he has pulled it down, and made use of all the stones for a mill-dam, and yet without any intention of preserving his fame to posterity, as the destroyer of the Temple of Diana had. No other motive had this Gothic knight, but to procure as many stones as he could have purchased in his own quarries for five shillings.”

Stuart put it well –

“the ancient Sacellum, which had stood for fifteen centuries by the ‘dark winding Carron,’ facing unshaken the rude buffets of time, spared alike by Pict and Scot, by Saxon, Norman, and Dane; which, if what is writ be true, had beheld the passing legions of Severus, the gathering of Ossian’s heroes, the adventurous march of Wallace, the fight of Bannockburn; this venerable monument of departed ages; fell in the year 1743” (Stuart 1852).

The removal of the Roman monument allowed Michael Bruce and his successors to continue the improvement of his policy grounds. That part of the common highway on the west side of the house was planted with trees – as can be seen on Roy’s map of 1755. The tree-lined avenue started at Pathfoot (near the present boundary wall for Carron Dams) and up the O’on Path to well beyond Stenhouse Castle. The Broom Lone across Stenhouse Muir was effectively closed and became a footpath. Around 1815 even the O’on Path was closed to the public and a better engineered road was provided further to the east on the boundary of the estate – now known as Alloa Road. A new access road was also constructed for Stenhouse Castle some forty yards to the west of the former path and the South Lodge was built at its junction with the main road to Larbert. Then, around 1830 the Broom Lone was dug up and the right of way eradicated (Stirling Observer, 5 March 1863, 6).

In 2014 Tom Welsh pointed out that the accepted site of Arthur’s Oven might be wrong. The exact site was so ingrained into the record that at first this seemed to be improbable but, as he pointed out, the written record came down to one reference – that of Rev John Bonar of Larbert Parish Church. It was published as part of the New Statistical Account in 1845, two years after the Disruption which caused Bonar to defect to the Free Church. It was very precise about the location –

“on a bank sloping to the south or south by east, about 300 feet to the north of the point where is now the north-west corner of the Carron Iron-works. There is a piece of ground of the extent of about 50 feet square, which had a well sunk in it, and is used as a washing green by the inhabitants of the adjacent houses.”

By then a century had passed since the demolition of the structure and the site mentioned was certainly in the right sort of area adjacent to the O’on Path. Bonar’s site was to be the focus of attention for the next century and a half. In 1868 Robert Stuart, the author of Caledonia Romana, conducted an investigation of the “supposed site,” without success. Sir William Bruce and Colonel Dundas were involved, which suggests that trial trenching took place. Despite this negative result faith in the site continued and when Falkirk Museum opened in Dollar Park in 1926 it displayed a map of it which was endorsed

“According to Ordnance Survey and verified by Mr Mungo Buchanan who got it from a man who got it from a Mr Kerr who had seen what was left of the foundation. 20.5.21.” (Falkirk Archives a 9.190).

O.G.S Crawford visited the traditional site in the 1940s noting that there was nothing to see but that excavation might reveal some remains of the foundations. Consequently in 1950 Kenneth Steer, R.W. Feachem and A. MacLaren cut trenches across the site, finding that the topsoil was very shallow and that natural deposits lay just below the surface. Steer concluded that

“Clerk was not exaggerating when he informed Gale that, at the time of demolition, ‘even the very foundation-stones were raised’; and it must be concluded that the whole area has subsequently been levelled off” (Steer 1960, 100).

By the end of that decade even this site was under threat from the inexorable expansion of housing estates. In 1958 a Roman coin was discovered nearby during the construction work – though the location provided was far vaguer even than that of Arthur’s Oven (DES 1958, 37). The coin was, perhaps, an antoninianus, of Trajan Decius (249-251AD). A few years later, in 1964, Doreen Hunter, the curator of Falkirk Museum, reported that

“Preparation of the ground south of Stenhouse Castle discovered a number of stones unlikely to have come from ‘ Forge Row’ the cottages which once stood near at hand. Three of them—two 2ft. 6 ins. cubes, a third slightly irregular—are unlikely to have come from any building in the vicinity but Arthur’s O’on… A small amount of mediaeval pottery was found, but no other trace of occupation.” (DES 1964, 46).

The site was lost. However, in 2007 during yet more house construction 450m to the north-east a fragment of dressed sandstone was found re-used in the wall of a 16th century pottery kiln. The face carried two horizontal lines of moulding and appears to have come from a Roman altar (Hall 2009). It is now in Falkirk Museum, accession. no. 2009-15-661.

Attention had also focused on the damhead across the River Carron which the stones from Arthur’s Oven had been used to repair. It was felt that it might be possible to recover some of the dressed stones from it and on 18 June 1870 the Falkirk Herald reported:

“We have been favoured by Mr Kerr, Carron, with a drawing and measurements taken by his grandfather, Mr Hayworth, of one of the stones of Arthur’s O’on, which was found “at Carrondamhead” in 1803. On comparing Mr Hayworth’s drawing with Mr Jelf’s we perceive that there is a resemblance in the shape of the stone to that of the arch stones of the door as shewn in the drawing of the latter gentleman. But we shall leave it to those who are better able to decide on such matters to say whether the stone found in 1803 is likely to have been one of those arch stones. If it has been, it shews that the extrados has been as shewn on Mr Jelf’s drawing.”

Mitchell made an unsuccessful attempt in the early 1990s to re-locate the damhead which may have been buried within the later precinct of the Carron Iron Works (Mitchell nd). It was hoped to recover some of the stones of Arthur’s Oven which may still be recognisable as the repair work of 1743 is unlikely to have reworked them.

The exact site of the damhead, like that of Arthur’s Oven is uncertain and difficult to access. It would appear that both are lost. However, it is possible that the precise location for Arthur’s Oven was slightly displaced by an over reliance upon Bonar’s account. 300ft sounds more like an estimate than a measurement. Register House Plan 1497 entitled “Plan of properties on the River Carron, Stirlingshire,” drawn up for the Carron Company around 1768, shows the site of “The Temple of Terminus/ alias Arthur’s Oven” further north up the hill than the traditionally accepted site. This would agree with the bend in the road observed in Stukeley’s drawings and would mean that the correct location is NS 8785 8285.

It would seem that Arthur’s Oven was a tropaeum commemorating a major Roman victory in Scotland – possibly even that at Mons Graupius. The site of the battle won by the Roman army has since been lost to history but we may be able to recover the site of Arthur’s Oven justifying the title of this article – “Arthur’s Oven; a battle won, and lost.”

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 1992 | ‘Along and Across the River Carron: a history of communications on the lower reaches of the River Carron,’ Calatria 2, 49-85. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 1996 | ‘The Graveyards of the Falkirk District: Part I,” Calatria 9, 1-34. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 2016 | ‘The Early Archaeology of Falkirk,’ Calatria 33, 1-26. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 2021 | The Antonine Wall in Falkirk District. |

| Bonar, J. | 1845 | New Statistical Account of Scotland – Parish of Larbert. |

| Boon, G. | 1972 | Isca: the Roman Legionary Fortress at Caerleon, Mon. |

| Breeze, D.J. | 2014 | ‘Commemorating the Wall: Roman sculpture and inscriptions from Hadrian’s Wall,’ in Collins, R. & McIntosh, F. (ed), 59-64, |

| Breeze, D.J. & Hanson, W.S. | 2020 | The Antonine Wall: Papers in Honour of Professor Lawrence Keppie. |

| Breeze, D.J. & Mann, J.C. | 1987 | ‘Ptolemy, Tacitus and the Tribes of North Britain.’ Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 117 (1987), 85-91. |

| Brickstock, R | 2020 | ‘Pre-Antonine Coins from the Antonine Wall,’ in Breeze & Hanson (ed) 61-66. |

| Carroll, D.F. | 1996 | Arturius, a Quest for Camelot. |

| Collins, R. & McIntosh, F. | 2014 | Life in the Limes. |

| Coulston, J.C. & Phillips, E.J. | 1988 | Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani, Corpus of Sculpture of the Roman World. Great Britain I, 6, Hadrian’s Wall West of the North Tyne, and Carlisle. |

| Hall, D. | 2009 | Recent Excavations of Pottery Kilns and Workshops at New Carron Road, Stenhousemuir, 2007,” Medieval Ceramics 30 (2006-2008), 3-20. |

| Hunter, F. | 2001 | ‘Unpublished Roman finds from the Falkirk Area,’ Calatria 15, 111-123. |

| Hunter, F. | 2020 | ‘…one of the most remarkable traces of Roman art… in the vicinity of the Antonine Wall.’ A forgotten funerary urn of Egyptian travertine from Camelon, and related stone vessels from Castlecary.’ in Breeze & Hanson (ed) 233-253. |

| Ibarra, A. | 2014 | ‘Monumental interventions in the vacant landscape in the late Republic and early Empire,’ in Osborne 2014, 135-152. |

| Maxwell, G. | 1990 | A Battle Lost: Romans and Caledonians at Mons Graupius. |

| Mitchell | nd | A discussion of the maps which provide evidence that the stones from Arthur’s O’on are still in existence, buried beneath the land nearby. Unpublished. |

| Nimmo. W. | 1880 | The History of Stirlingshire (ed Gillespie, R.). |

| Osborne, J.F. | 2014 | Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. |

| Rivet, A.L.F. & Smith, C. | 1979 | The Place-Names of Roman Britain. |

| Spottiswoode, J. | The History of the Church of Scotland | |

| Tacitus | The Agricola and the Germania – Penguin Classics translated by H Mattingly. | |

| Stuart, R. | 1852 | Caledonia Romana: Descriptive Account of the Roman Antiquities of Scotland. 2nd ed. |

| Stukeley, W. | 1720 | An Account of a Roman Temple and other Antiquities near Graham’s Dike in Scotland. |

| Stukeley, W. | 1757 | The Medallic History of Marcus Aurelius Valerius Carausius Emperor in Britain. |

| Tatton-Brown, T.W.T. | 1980 | ‘Camelon, Arthur’s O’on and the main supply base for the Antonine Wall,’ Britannia 11, 340-343. |

| Welsh, T. | 2014 | Where stood Arthur’s O’on? (unpublished). |

| Woolliscroft, D. J. & Hoffman, B | 2006 | Rome’s First Frontier: The Flavian Occupation of Northern Scotland. |