Excavations in 2023

Introduction

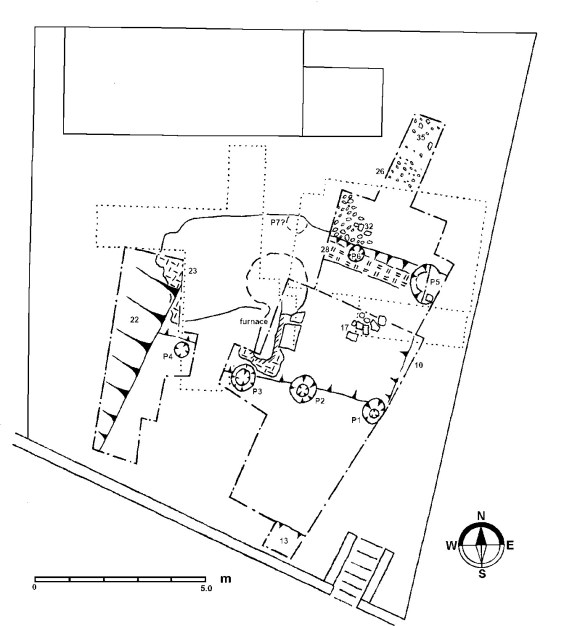

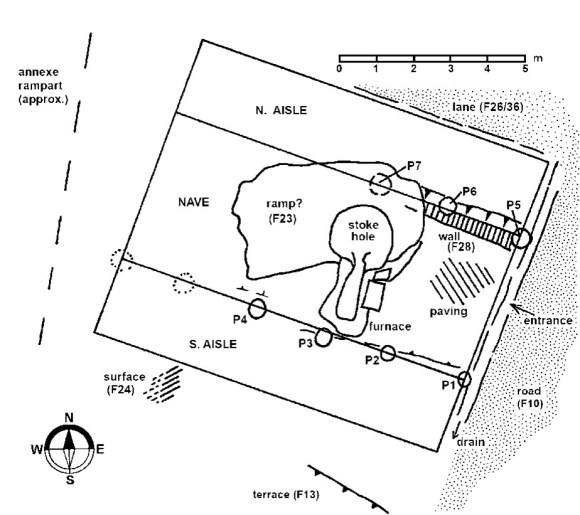

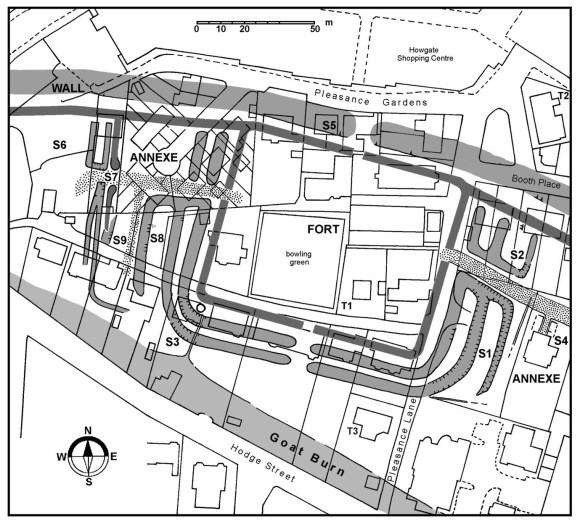

In 2017 the author and his hard-working diggers excavated three small trenches in a detached garden on the north side of South Pleasance Lane at NS 8859 7975 (Bailey 2021, 484-492). The results were very interesting though a little confusing. An iron-smelting furnace was found but the trenches were too small and awkwardly placed to positively identify any building in which it must have stood. The trench positions were dictated by the presence of a number of large trees. A sunken feature was noted along the south side of Trench 1 close to the baulk and although Trench 1A was then dug in this area to explore the lower terrace it was felt that, without the ability to explore the area yet further to the south, more detailed examination of these features would prove fruitless. Interpretation was further exacerbated by the policy of undertaking the minimum of intrusion into the Roman levels as the site was not under immediate threat of destruction. As a result, a substantial west/east raft of clay embedded with small angular sandstone fragments was tentatively identified as the base of the south rampart of the annexe located on the west side of the Roman fort and the terrace slope as the accompanying ditch.

A few years ago the owners of the garden plot cut the trees down at ground level and so, recognising the previous problems, it was decided to return to the site and open up new ground as well as examining those areas of the old trenches left in situ. The new excavation took place from 28 July to 10 August 2023.

Excavation

Trench III was placed to the south of Trench 1 and subsequently extended northwards into it. Three large tree stumps had to be removed in this process but it was found that the depth of overburden had protected the Roman levels from the roots. The topsoil averaged 0.3m deep and traces of “plough” marks were detected at its base. Below this was between 0.5 and 0.6m of an earlier cultivation soil – a leached orange-brown sandy loam (F6) containing green-glazed ware, 17th century tobacco pipes and a few medieval pottery sherds. One of the pipe bowls was found just above the yellow natural sand in the southern part of the trench (south of Post-hole 2) indicating that any Roman levels in that vicinity had been lost due to this horticultural activity.

The stepped construction trench (F12) for the stone retaining wall bordering South Pleasance Lane occurred at the south end of the trench, cutting an early 19th century pit (F11). 0.2m of the cultivation soil (F6) remained below F12 right up to the back of the wall, showing that the wall had been built from the lane. Only the south side of the wall was faced. 1.0m from the wall the natural sand was cut away to a depth of c0.24m forming a shelf upon which iron-panning had occurred (F13).

Phase 1

Broken blond sandstone and fragments of “tufa” occurred in all of the deposits indicating that it arrived with the first Roman occupation of the site (Bailey 2021, 488). It seems to have formed a thin spread of material. In Trench IV, which was placed to the west of Trench III, the tufa formed part of the fill of the earliest feature on the site.

Phase 2

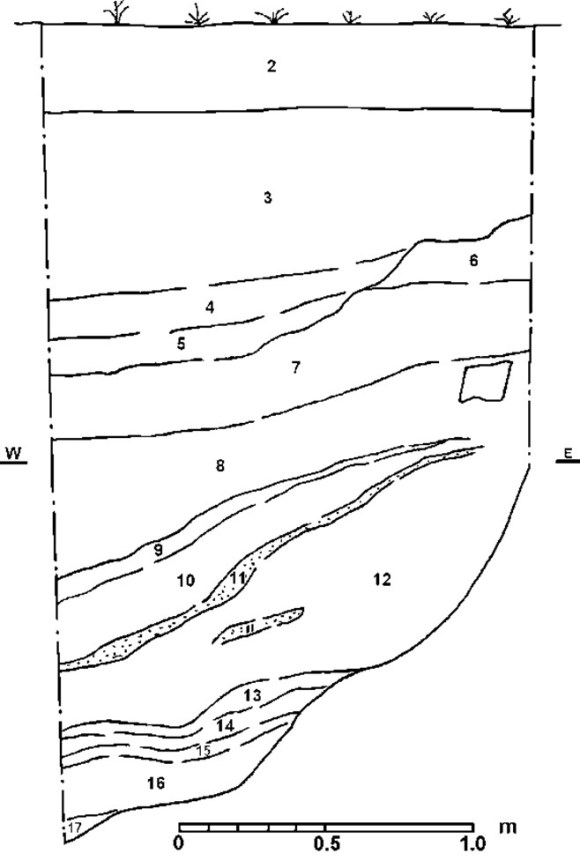

The earliest recognised feature was a large ditch in Trench IV aligned north/south (F22). It had been dug at least 2m deep into the natural sand and had been backfilled with clean sand resulting in tip lines (see section 1). One of the layers, about half way up, contained small fragments of the tufa material. The angle of the tip lines suggest that the ditch was in the region of 3.5m wide – a substantial defensive ditch.

Phase 3

The ditch was clearly deliberately backfilled after a relatively short period and Building A was then constructed over it. Section 1 shows the clay “floor” (layer 6, F23) covering the eastern section of the ditch with slumping occurring towards the centre of the ditch.

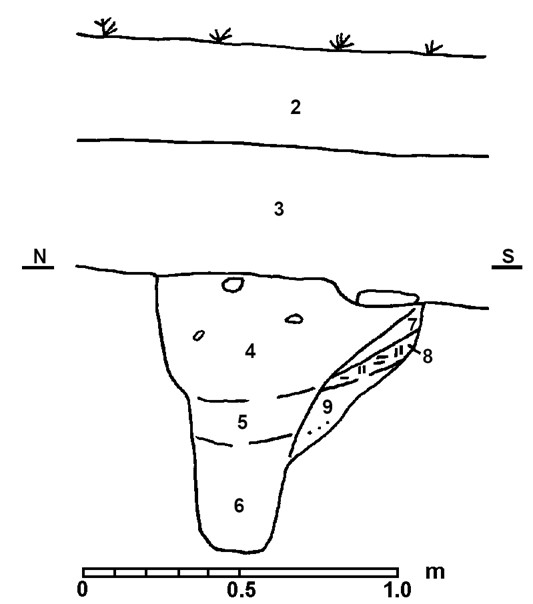

Building A consisted of two W/E rows of posts set in substantial post-holes, each dug around 0.9m into the natural. The ovoid post pits were 0.6m in diameter at the top, narrowing at a depth of 0.4m to 0.25 at the bottom. They were set roughly 2.0m apart, centre to centre, and the distance between the rows was 4.3m. The southern row, P1-4, were positioned just outside of a shallow cut in the natural sand which provided a sunken platform to the north upon which the floor had been placed.

The northern row, P5-7 (P7 can be postulated from a bulge in the plan of F23 in the 2017 trench), lay just inside a much deeper counter cut in the natural sand which represented the northern side of the floor terrace. A 0.2m wide strip of clean compacted clay (F28) had been laid between these northern posts. It was made up of discrete areas of yellow, orange, grey and blue-grey clay which suggested that it may have been laid as a series of large unfired blocks to form a terrace wall (cf Brough on Humber Jones 1975, 132). It survived to a height of 0.45m.

The clay blocks had been packed tightly around the structural posts in Post-holes 5 and 6, making the post voids initially hard to distinguish.

All of the post-holes incorporated fragments of tufa and broken sandstone as packing.

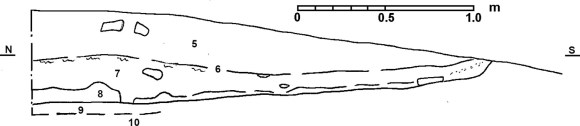

The natural sand had been cut immediately to the east of Post-holes 1 and 5 to form the sub-floor. Upon this broken sandstone slabs had been set in clay. Many of the slabs lay at an angle to the horizontal in a line parallel to the building to form a drain along the western side of the north/south Roman road found in 2017.

The floor (F30) of Building A consisted of a small number of flat slabs, roughly laid down the centre near the probable entrance from the road (F10), covered with grey-blue clay. Near the furnace this was covered with a thin layer of compacted dust and iron panning which created a flat and very hard durable surface. Incorporated into this floor were two large flat slabs which formed the east side of the iron smelting furnace discovered in 2017. Although some small flat stones occurred further south they were not integrated into the same hard matrix but sat in slightly oxidised compacted sand. In the northern third of the building the floor was overlaid by clay derived from F28. The orange-brown sandy loam layer (F27) above the floor (see Section 2) tapered from a few centimetres at the south end of the building to 0.18m in the centre. It contained a small amount of Roman pottery, nails and shoes. Its depth and location suggest that it represents a demolition deposit rather than an occupation level. Above F27 was a thin layer of similar material containing a large number of nail heads and iron panning and patches of charcoal (F29). The charcoal was spread throughout the building with a noticeable concentration curving around the south-east corner. The layer above this, F25, was mottled orange and grey sandy loam reminiscent of decayed turf. Like F27 it tapered from nothing in the south to 0.26 in the centre of the building.

The furnace (F50) was examined in 2017 and is described in Bailey 2021. The chimney lay at the south end and the stoke-hole at the north. The latter had been filled with the yellow clay which incorporated small angular pieces of sandstone (F23). This material was found in the northern end of Trench IV over the line of Ditch F22 and its northern extent was mapped in 2017. It overlapped the clay wall F28 and was clearly distinct from it. It had been heavily compacted – to such an extent that it was difficult to section in 2017 (and 2023) and was tentatively identified as a rampart base. The stone had been deliberately added to the clay and its location and distribution now indicates that it formed a floor within Building A which was associated with the working of the furnace.

The terrace to the north of P5-7 had a small number of sandstone fragments trodden into the natural sand. There was also a discrete dump of these stones, slightly larger in size, in the western edge of the trench. They had been laid against Wall F28 and a few had slipped into P6 following the extraction of the post. They formed a wedge shape in section, petering out to the north.

2.1m north of the terrace which marked the north side of F28 was a spread of small flat sandstone fragments. The first 0.2m (F26) had been deliberately laid flat and formed a good road surface, but proceeding further north the stones were also set on edge suggesting that they formed the foundation for a cambered lane (F35) and that there the road surface had been removed by later activity.

Discussion

Although there was no structural evidence for activity on the site before the arrival of the Roman army in the second century AD, the find of a flint flake in post-hole 4 suggests that the general area was occupied in the prehistoric period. The earliest material on the site consists of the broken sandstone and “tufa.” The nature of this latter mineral (or slag) is still to be examined but it would seem that these materials were associated with the construction of the Antonine Wall fort immediately to the east and were thus contemporary with the tile kiln found in the grounds of Adrian House (Bailey 2020, 478-483). That kiln had been cut by the digging of a third ditch on the west side of the fort. The short-lived nature of Ditch F22 at the current site would be consistent with a similar sequence, providing a fourth large ditch. There was comparatively little material in the base of the ditch which had been washed in. Above this the tufa and broken stone in the deliberate backfill tipping layers helps to confirm this.

Most of the Wall forts were defended by two ditches, though three are often found fronting vulnerable approaches were the topography did not give additional cover (Bailey 2020, 68). Four ditches are rarely found – they occur at the southern end of the western defences at Mumrills and on the north and east sides at Old Kilpatrick. In both of these cases the slopes were disadvantageous to the positioning of the fort; that it not the case on the west side of the Falkirk fort. There the fort sits on a hill overlooking the valley of the West Burn. The provision of four ditches must have been due to some other aspect of the setting. The proximity of a native settlement is likely, but all the available evidence indicates that it lay to the north of the Wall barrier. Perhaps the likeliest explanation for the plethora of ditches is the nature of the soils. Falkirk sits on a ridge of sand and any ditches cut into this would have silted up relatively fast. The corollary to that was that the digging of the ditches was easy!

The lower deposits in the ditch (layers 13-17 in Section 1) indicate that it was probably open for several seasons before being deliberately backfilled using clean sand and debris from the early building yard. This was probably derived from the upcast mounds. The reason for the infilling of the ditch was to enable the construction of Building A which we may confidently associate with the provision of a defended annexe. Although no special measures were taken to consolidate the ditch fill, the builders would have been well aware of its presence. This may explain the absence of a post in the southern wall, and if the ditch was indeed 3.5m wide the next post in the line would have been founded on more solid ground. The clay platform (F23) may have been an attempt to raft the area.

Building A had two rows of substantial posts and we can justifiably call it an aisled building (sometimes known as basilican or “basilical,” Ward 1911, 174-184). These posts would have been the main structural element of the building supporting a tall central hall (or nave), with lower aisles to either side. This form of barn-like structure is a well known type in Roman Britain and occurs in large numbers in England on villa sites. It is also known in industrial complexes such as Wilderspool (for a discussion see Bailey 2022) which are considered to be military supply posts. These workshops were the industrial sheds of Roman Britain. Four posts-holes were located in the south line (P1-4) at intervals of 2.0m centre to centre. Using the post shafts rather than the centre of the post-holes as the line of the wall shows that the third post (P3) was slightly south of its true position and we can only assume that this displacement was due to the close proximity of the iron furnace, though why that would have been necessary is questionable. P1 lay hard up against the roadside drain on the east, as did P5 in the northern row, and we can assume that an entrance existed in this gable on line with the paving F17. How far the building extended westward is not known. It seems unlikely that P4 was its limit in that direction and the floor (F23) continued a little further. The known presence of the earlier ditch may account for the absence of a post at the regular distance – though at Mumrills such problems were overcome by the use of a post pad (Bailey 2021, 268-9). Careful search of the ditch at Falkirk showed that this did not occur there. The west rampart of the annexe was a little over 12m distant from the north/south street (F10) which would have given space for a row of five or six posts. The south and north lines of posts were set 4.2m apart and the normal proportions of aisled buildings would suggest that six posts in each row would be appropriate. The nave was the focus of the industrial activity with the iron smelting furnace occupying its complete width. The floor of the nave was set into the natural sand and carefully prepared with small flagstones covered with a thin coat of clay. In working life this accumulated a dusty layer and constant use evidently compacted the layer into a hard flat surface. The north side of the nave was bounded by a clay block wall set between the main posts. This wall (F28) was at least 0.45m tall and retained the ground on the far side. The width and nature of this material meant that it also prevented water from entering the nave. The working of the iron at high temperatures meant that this was essential if steam was not to cause practical problems.

The terrace above F28 had been levelled using broken sandstone and beyond that was a minor lane (F35). Although the Roman levels did not survive well here there seems to be a gap of 2.1m between the lane and wall F28 which could have been occupied by an aisle. Sherds of Roman pottery trampled into the natural sand here would support this. The terrace between this northern aisle and the nave was 0.4m in height and so it may have been that the roof slope on this side of the building was continuous,

whereas that for a south aisle would have been stepped. Unfortunately the area which would have been occupied by the south aisle was disturbed by the 17th century cultivation – a tobacco pipe was found almost directly upon the natural at this point. Again, the distance between the southern row of post-holes and the terrace to the south was 4m, more than sufficient to accommodate this lean-to. Having a step within the building would have presented a minor inconvenience and it is possible that the clay raft F23 which followed the hill slope worked as a ramp – though this may have been an accident of survival. That the furnace occupied the full width of the nave demands such aisles.

The lower terrace (F13) may have been created to house a second building in the annexe. If so, it may be associated with the patch of small stone and clay (F24) found in the upper fill of Ditch F22 at the southern end of Trench IV. The strike of the hill slope is from north-north-east to south-south-west and the terrace would have been perpendicular to that. However, it is also possible that terrace F13 was dug much later in the medieval period to provide a level platform for the early predecessor of South Pleasance Lane.

At the end of its life Building A was deliberately demolished. The main posts were removed and chocking stones fell into the voids that they left. First, however, rubbish was strewn over the floor and internal features were slighted. The rubbish included shoes and a handful of cooking pots. Wall F28 was pushed over. The roof was then collapsed. Although speculative, it is possible that the roof was covered with turf and is represented in the archaeological record as the decayed turf suspected in layer F25 – it did not occur beyond the confines of the building (though again this may be an accident of survival). Immediately below the decayed turf was a layer containing numerous nails and some charcoal (F29) which could have been the supporting frame.

After the departure of the Roman army there is no material record of activity on the site until the deposition of 12/13th century white gritty ware. It is probable that the area was under cultivation in the interval. Turf from the common muir would have been brought in as fertiliser raising the ground level. A few sherds of early green-glazed wares were also found and then in the 17th century tobacco pipes were left behind. Two complete pipe bowls were recovered, both bearing the star-shaped stamp of a Stirling manufacturer. At this time the main road from the west probably ran along the top of Arnothill, following the Antonine Wall, crossing the valley of the West Burn near the site of the later Erskine Church, and ascending the hill of Falkirk by a lane to Pleasance Square. This route took it along the northern boundary of the excavation site. The area was part of the fifteenth parts of the lands of Falkirk which had been granted to the Livingstones of Westquarter who for decades ran the town. The family’s Great Lodging was on the High Street and the Pleasance formed part of the formal gardens or pleasure ground. The name “Pleasants” is found as early as 1694 (Reid 2010, 372). By the 1720s the Livingstones were in financial difficulties and in 1728 James Livingstone of Westquarter handed the land over to creditors in order to keep them at bay. It was subsequently divided into smaller lots and was used as gardens and allotments by the residents of the small town. The garden plots were served by a network of small paths – a pattern still recognisable to this day. In the 1880s houses were constructed along the south side of South Pleasance Lane and for this purpose various plats were amalgamated.

Finds

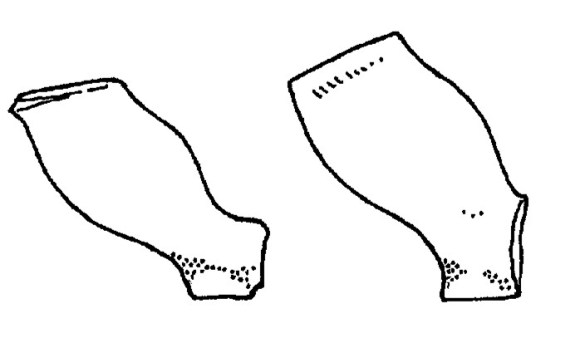

The Roman pottery consisted of the usual range of cooking bowls and jars with black-burnished wares and grey wares occurring in roughly equal numbers. The grey wares are a very good imitation of black-burnished, as indeed are the smaller numbers of Falkirk ware vessels. These everyday pots were found in floor trample, occupation and demolition levels showing that they were probably used in Building A. In all, only about twelve vessels are represented. Three light grey ware jars (Gillam 1961, no. 33 & 38 & 55), a heavier grey ware jar (Gillam 1961, no 57), five black-burnished bowls (Gillam 1961, no 38, 40 & 42, 328), a black-burnished jar (Gillam 1961, no 34), a Falkirk ware jar (2023-89), a narrow-necked black-burnished jar (Gillam 1961, no 30). The grey ware jar in thick hard (metallic) fabric with a dark external face bearing a groove on the shoulder with two broad swirling or wavy lines is present in six sherds (2023-54, 82, 109, 116). One example of the Falkirk ware shows a manufacturing defect which resulted in the loss of its burnished surface over a large area (2023-71). Whilst it would still have been saleable, this would be more appropriate to a local product which had not travelled far.

The fragment of mortarium (2023-74), the Rhenish beaker (2023-106), a small amount of amphora (2023-10 & 14 weighing only 114g), the oxidised jar (2023-38), the small fragment of grooved ware (2023-45), and the samian (2023-3, 34 & 36), were found only in the demolition layers and may therefore have been dumped from elsewhere.

The hobnails in the demolition levels were sufficient in number to represent more than one shoe. As commonly occurs in the sandy soils of Falkirk, the corrosion products from the nails had impregnated the leather and bonded them together.

- Bronze buckle with tapering tail and pelta shaped head. The sides are of chamfered rectangular section and the tongue is round-sectioned. There are signs of the fabric of the belt in the corrosion products. This is one of the most ubiquitous forms of Roman military buckle and was long-lived. Length of tongue 18mm. 2023-125 (F27).

- Glass bottle – base sherd in thick aquamarine glass with many small air bubbles from a square bottle with an embossed basal ring. L.7cm. 2023-16 (F33).

- Window glass – a flat piece of glass with a matt finish on one side. L47mm; T2mm. 2023-17 (F33).

- Struck flint flake (2023-101), F53.

- Tobacco pipe – complete bowl with star-stamp on the heel, 1640-1660. Made in Stirling. 2023-32 (F2).

- Tobacco pipe – complete bowl with star-stamp on the heel, 1660-1680. Made in Stirling (found immediately above the natural sand in the probable area of the south aisle). 2023-33 (F6).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all of those who contributed to the success of the excavation – to Jim & Linda Hendry for permission to upturn the garden and for sending the “bringer of cakes” with an ample provision of sustenance. Another local resident, Stewart Crawford, was also generous with drinks.

The work moving enormous quantities of earth fell on the hard-working volunteers: Ben Bright, Alan Calder, Ross Dempster, Stacey Duffy, Judith Fraser, David Gibson, Emma Gillanders, Richard Gillanders, Bruce Harvey, Ian Hawkins, Sergio Lopez, Ian McAdams, Donald Macleish, Kenny Macleish, Andrew Marshall, Andrew Packmen, Jayden Sandys, and John Strachan.

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B | 2021 | The Antonine Wall in Falkirk District. |

| Bailey, G.B | 2022 | ‘Excavation in Mumrills Annexe, 2022.’ |

| Hadman J. | 1978 | ‘Aisled buildings in Roman Britain,’ in Todd (ed) Studies in the Roman British Villa., 187-195. |

| Jones, M.J. | 1975 | Roman Fort-Defences to AD 117. |

| Smith, J.T. | 1963 | ‘Romano-British Aisled Houses,’ Archaeol. J 120, 1-30. |

| Ward, J. | 1911 | Romano-British Buildings and Earthworks. |

Contexts at a glance

- 2 Black loam – topsoil.

- 6 orange-brown sandy loam – leached 17th century cultivation soil.

- 9 early 19th century pit seen in the east section of Trench III cut by F8.

- 10 N/S Roman road surfaced with small flat pieces of stone and pottery

- 11 Slabs of burnt and unburnt sandstone pitched at an oblique angle and set in clay –

…………………. roadside drain. - 12 Black loam with 20th century material –

…………………………………………… construction trench for modern boundary wall. - 13 Shelf/terrace with iron-panned base at the south end of Trench III.

- 17 rough paving forming the foundation of the floor of Building A.

- 18 mottled yellow sand along west side of trench IV above ditch F22.

- 19 mixed yellow-brown sandy loam & grey sand in SW corner of Trench IV –

……………… upper fill of Ditch F22. - 20 Small stones and lumps of clay forming a layer in the fill of Ditch F22

……………….. at the south end of Trench IV. - 21 Orange-brown sandy loam over ditch, Trench IV – 17th century subsidence into ditch.

- 22 Large N/S ditch in Trench IV – fort ditch.

- 23 Yellow clay with broken pieces of sandstone – floor of Building A.

- 24 Small stones and patches of clay in southern end of Ditch F22,

………….. c0.2m below the level of the natural – feature connected with the lower terrace. - 25 mottled orange and grey sandy loam – turf roofing material.

- 26 small flat pieces sandstone laid flat – gutter for lane F35

- 27 orange-brown sandy loam layer above the floor F30

- 28 Clean yellow, orange, grey and blue-grey clay forming a wall

………………. between the northern line of post-holes. - 29 Thin layer of orange-brown sand with iron-panning & nail heads – roof frame.

- 30 Compact dust. Clay & ironpanning – Floor of Building A.

- 32 Sandstone fragments in north aisle – levelling up of terrace.

- 33 mixed orange-brown sandy loam and clay adjacent to P 5.

- 34 Roman trample in north aisle.

- 35 flat pieces of sandstone -W/E lane along the N side of Building A.

- 36 Small depression just SW of P4 in Trench IV.

- 50 Post-hole 1

- 52 post-hole 2

- 53 post hole 3

- 54 post-hole 4

- 55 post-hole 5