Around 1805 the Duke of Hamilton had a staging inn erected to the east of the Town House. This was close to the harbour and specifically catered for the foreign ship masters. It was known as the “Black Bull,” and changed its name to the better sounding “Douglas Hotel” in the early 1850s. It was part of the increasing infrastructure in the town that owed its existence to the trade done at the harbour. To its south-east, the informal area in front of Regent House became the new market place and fresh water was fed into it from the high ground to the south. A well-head or fountain was built there in 1817 and named “St John’s Well.” It was convenient for the ships calling at the harbour and sailors were often seen filling barrels from it. Whilst they waited they chatted to the local girls and exchanged news. Once full, the sailors would lash the barrel to a long pole and then carry it over their shoulders back to the ship, the barrel swaying from side to side as they progressed.

The failure of the Bo’ness Canal had had a profound effect upon the fortunes of the harbour at Bo’ness. The opening of a Custom House in Grangemouth in 1810 made matters worse. Not only did the development of Grangemouth as an alternative port take trade away, but now the merchants had very little capital with which to promote Bo’ness. This was merely exacerbated by the war with France. Trade gradually fell away from Bo’ness, leaving the harbour in a decayed and languishing condition.

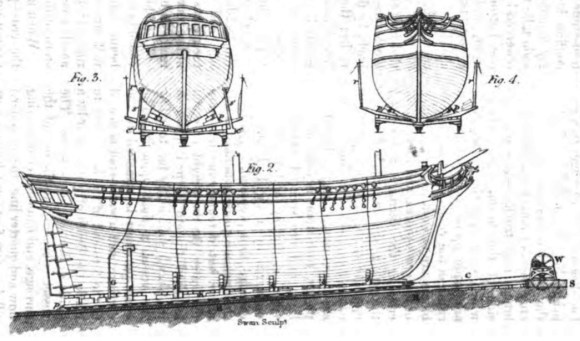

By an Act of Parliament passed in 1816 the Harbour Trustees were empowered to levy dues on ships with “any British ship in putting a rope ashore and making fast to the quay to pay 2½ d per ton.” This money was to be applied to maintaining and improving the harbour. The first step in its recovery was to be the construction of a wet dock or slip – the latter was chosen because it was cheaper. In 1820 the Duke of Hamilton subscribed £105 to the project and on 11 September 1820 it was reported that a letter had been received from Thomas Morton, Leith, offering to execute the slip, with all its appendages and necessary excavation and building, for £865. The Trustees then set about raising the rest of the money. Morton’s offer was not accepted until it was seen what subscriptions were obtained. Meanwhile, Morton was requested to guarantee the work for two years, and to extend the size of the slip so that it might be capable of taking vessels up to 360 tons register. By 4 December the subscriptions promised came to close enough to what was required to allow Morton’s offer to be accepted. This slip was only the second of the kind he erected in the country, being ready in 1822.

| Robt. Bauchop for the Duke of Hamilton | £105 | Brought Forward | £505 |

| James and Andrew Tod | 50 | Alexander Steell, | 25 |

| John Padon | 25 | Alexander Rowan | 25 |

| William Henderson | 25 | John Anderson | 25 |

| James Henry | 25 | Rev. Robert Rennie | 25 |

| Walter Grindlay | 25 | John Henderson | 25 |

| George Paterson | 25 | J. & C. Green | 25 |

| George Henderson | 25 | Henry Rymer | 25 |

| Tobias Mitchell | 25 | Mrs. M. per J. Merchant | 25 |

| James John Cadell | 25 | William Shairp | 25 |

| James Robertson | 25 | William. Calder | 25 |

| John Hardie | 25 | Robert Henderson, jun | 25 |

| James Shaw | 25 | John Thomson | 25 |

| Arthur Thomson | 25 | George Wallace | 25 |

| Robert Henderson | 25 | Robert Bauchop | 25 |

| David Thomson | 25 | J. P. for Hay Bums | 25 |

| Thomas Boag | 25 | ||

| Over | £505 | £905 |

The slip was built in the westernmost section of the reservoir basin and projected into the landward end of the harbour. In order to reduce the gradient it was extended south into the grounds of the Town House (still called the coal fauld by the locals), the property of the Duke of Hamilton. It was held as the joint property of the subscribers. The rates for the use of the slip were to be fixed by a majority of them; one vote per shares of £25. The Harbour Trustees were to maintain the new basin wall on its east, and the harbourmaster was to take charge of the slip and collect the dues thereof. In consideration of all this, and of the money already expended towards the accommodation of the slip, one-half of the revenue arising from it, after deducting the rent of that part of the premises taken by the trustees from the Duke of Hamilton, was to form a part of the town’s funds (Salmon 1913, 260-1).

The nature of the Slip can be gathered from an advert of 1824:

“Thomas Morton, ship-builder, Leith, begs to solicit the attention of those interested in maritime affairs, to a new method invented by him, of building ships out of the water, upon an inclined plane, for repairs, & c for which he holds his Majesty’s Letters Patent for the united kingdom and colonies.

The principal object of this invention is to provide a cheap substitute for dry docks, where it has not been thought expedient or practicable to construct them; and both in point of economy and dispatch, it has been found completely to answer the purpose for which it was originally intended. The Patent Slip, after the extensive experience that has now been had of it, is admitted to possess the following advantages:

- .A durable and substantial Slip may be constructed, under favourable circumstances, at about one tenth of the expense of a dry dock, and be laid down in situations where it is almost impossible, from the nature of the ground, or a want of a rise and fall of the tide, to have a dock built.

- The whole apparatus can be removed from place to another, and be carried on ship board.

- Where a sufficient length of Slip can be obtained, a number of vessels may be upon it at once; and in point of fact, more than one are often on the Slips already constructed, and under repair at the same time.

- Among the other advantages peculiar to the slip, it may be observed, that every part of the vessel being above ground, the air has a free circulation to her bottom and all round her; in executing the repairs the men work with much more comfort, and of course more expeditiously; and, in winter especially, they have better and longer light than within the walls of a dry dock, while considerable time is saved in the carriage of the necessary materials. The vessel, in short, is in a similar situation to one upon a building slip.

- No previous preparation of bilge-ways is necessary, as the vessel is blocked upon her keel, the same as if in a dock; and she is exposed to no strain whatever, the mechanical power being solely attached to the carriage which supports her, and upon which she is hauled up.

- A ship may be hauled up, have her bottom inspected, and even get a trifling repair, and be launched the same tide; and the process of repairing one vessel is never interrupted by the hauling up of another – an interruption that takes place in docks from the necessity of letting in the water when another vessel is to be admitted.

- A vessel is hauled up at the rate of 2 ½ to five feet per minute, by six men to every 100 tons; so that the expense, both of taking up and launching, one of from 300 to 500 tons, does not exceed forty shillings…

Ten Patent Slips have been laid down, and may be seen in constant use in the following places, viz Dumbarton, Borrowstounness, Irvine, Aberdeen and Leith, in Scotland; at Whitehaven and Workington, in England; and at Waterford, in Ireland. Licences have also been granted for the construction and use of several others in England, and at Greenock and other Ports in the Clyde; and there is reason to believe that they will soon be introduced into many of the other seaports of the United Kingdom.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 14 February 1824).

The main user of the Bo’ness Slip in 1825 was Thomas Boag, shipbuilder. After his death in 1832 the Trustees seem to have struggled to get another lessee, but in 1845 Thomas Gray, shipbuilder, was recorded as launching ships there. He was there until around 1852. Sometime later the slip was leased for a few years to BFG Meldrum. Together they built around 20 vessels at the Slip.

| YEAR | SHIP’S NAME | BUILDER | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1804 | Rose | Sloop of 75 tons | Shaw & Hart |

| 1805 | Pomona | Brigantine of 150 tons | Shaw & Hart for J & J Rankin of Greenock |

| 1806 | Dispatch | Sloop of 70 tons | Shaw & Hart |

| 1807 | Jeanie | Sloop of 349 tons | Shaw & Hart for R & R Stewart of Greenock |

| 1814 | 231 tons | Shaw & Hart | |

| 1815 | Glasgow | Smack of 94 tons | Shaw & Hart for James McArthur |

| 1815 | Brilliant | Sloop of 97 tons | Shaw & Hart for Poe & Ritchie |

| 1816 | The Ladies’ Adventure | Schooner of 54 tons. Enlarged 1819 | |

| 1827 | Saint Ninian | Schooner of 101 tons | Thomas Boag for Archibald Liddell of Glasgow |

| 1827 | Bannockburn | Schooner of 100 tons | Thomas Boag for Archibald Liddell of Glasgow |

| 1828 | Johns | Schooner of 100 tons | Thomas Boag |

| 1847 | Ebenezer | Schooner of 81 tons | Thomas Gray for Watson of Leith |

| 1851 | Isabella | Coasting schooner of 90 tons | Thomas Gray for G Harley of Limekilns |

| 1865 | Euphemia | Schooner of 98 tons | BFG Meldrum for S Ewart of Ayr |

| 1866 | Amelia | Schooner of 164 tons | BFG Meldrum for Meldrum & Co |

The 1843 Act changed the method of election of the trustees and arranged a rotation or period of service. Their number was also reduced, now being between 9 and 12. As the brewing in the town and neighbourhood had almost disappeared, the two pennies duty was dropped, and a local stent was raised. The trustees for the future were known as “the trustees for the town and harbour.”

The Slip had been a success in retaining the shipbuilding industry, but had little impact upon shipping.

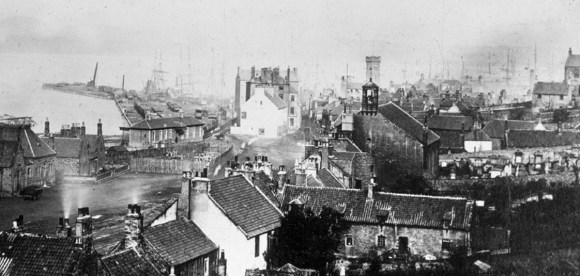

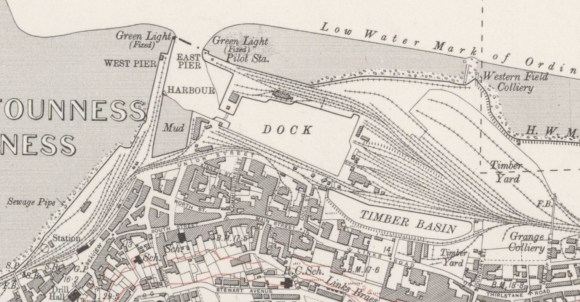

It had been a false dawn and true recovery began with the establishment of an enormous ironworks at Kinneil in 1843 by John Wilson of Dundyvan. It had four blast furnaces and in order to exploit the coal and iron reserves over a wider area a railway connection was promoted with the Slamannan Railway at Manuel, belonging to the Monklands Railway, also giving it a link to the Edinburgh to Glasgow Line. The Bo’ness branch opened in 1851 and although the Monklands Railway Company had, by the permitting Act, a right to lease the harbour, this was not taken up. The first section of the railway to be opened carried the pig iron from the Kinneil works to the West Pier, saving much carting. For this the old waggonway at Bailies Pier was widened. In December 1851 steam cranes were erected on the quay to aid handling. As the railway cut off a large section of the foreshore, the Railway Company had to construct a promenade for the public to use. This lay along the north side of the track and required a sea wall, similar to the arrangement still found at Culross.

With Meldrum’s departure for Burntisland, shipbuilding in Bo’ness ceased and in 1867 the Slip was leased to a Mr Pollock who was in charge of the punts used to remove mud from the harbour. The punts and a small steamer were kept at the Slip. This, however, did not continue for long. There had been for some years talk about major reconstruction of the harbour. It was decided to dismantle the patent slip, which had not fulfilled expectations of its usefulness. It was eventually sold to John Scott & Sons of Inverkeithing Foundry for a mere £80. Meldrum died in Edinburgh on 8 February 1873 and so suggestions that he built ships on the foreshore after that date are far from the mark.

The removal of the Slip was part of a major new project to provide rail access to the East Pier and beyond. In order to get the lines to that area it was necessary to fill in the reservoir basin and the southern part of the Slip – allowing the northern half of the Slip to be returned to quayage. This required new embankments and the strengthening of existing walls. The proposal would take a great deal of traffic off the streets and the town’s surveyor, Mr Paul, prepared plans. Early in September 1869 Samuel Mason, general manager to the North British Railway Company, stated that the company was willing, at its own cost, to form the connecting lines between the Bo’ness station sidings on the one hand, and the east and central piers on the other hand, and to lay down turntables, provided that the Harbour Trustees renewed the quay wall on the eastern pier; extended the central pier so as to give additional berthage to two vessels; repaired substantially the eastern pier by the erection of a portion of new wall near the northern extremity of it; and made approachable the railway connection across the old Slip. The Company was to have the right to use the lines free of charge; to put down such cranes as it deemed necessary on the several piers; and to levy cranage dues at their discretion within a maximum of 6d per ton for steam cranes, and 3d per ton for manual power cranes. Much to the concern of the Harbour Trustees, the Railway Company also mooted extending the line to the harbour at Bridgeness. This was a private harbour belonging to the Cadell family, and as such was a rival. However, it was pointed out that it would also allow coal to be brought from Bridgeness to the harbour at Bo’ness (Falkirk Herald 4 September 1869, 2).

Initial work around the Slip was carried out in the summer of 1870 by Brock & Syme, contractors. A new flushing pipe was installed and mooring rings place on the new quays. It was January 1873 before an agreement was reached between the Trustees and the North British Railway Company as to the harbour extension and the improvement of the terminus accommodation, providing crossings over the railway and its extension to Bridgeness. The arrangement consisted of five heads:

“First. That the North British Railway Company, in their Bill to be presented to Parliament, apply for permission to renew their borrowing powers in favour of the Bo’ness Harbour Trustees, as contained in the Monklands Act of 1846, and to increase the amount to be so borrowed to £15,000, for the purpose of extending and improving the accommodation and facilities of the present harbour.

Second. That the North British Railway Company having expended a considerable sum of money in providing railway accommodation in connection with the harbour, it is agreed that they shall extend the railway over the east and west pier, as the same may be adjusted with the trustees, the whole to be described on a plan relative thereto; and they shall also erect cranes and turntables and other conveniences as the parties jointly concerned may deem necessary for the proper accommodation of the traffic of the port.

Third. That the North British Railway Company apply, during the ensuing session of Parliament, for compulsory powers to acquire the promenade, and close up the level crossings, and to acquire part of the fore-shore overlooking the existing station, all as set down in the plan relative thereto, in order to increase the accommodation for the traffic in and about the station and the harbour.

Fourth. Within fourteen days after the date when the Act containing the above provisions shall have received the royal assent, the North British Railway Company shall pay the Bo’ness Commissioners a sum of not less than £500 sterling, as may be agreed upon between them – the same to be paid and taken as a fair compensation in respect of the alienation of the level crossing.

Fifth. The North British Railway Company shall apply in the ensuing session of Parliament for power to extend their railway from Bo’ness station along the shore to Bridgeness.”

(Falkirk Herald 18 January 1873, 4).

The North British Railway had acquired the Slamannan line as part of the Monklands Railway in 1865. It evidently wanted a port on the east coast to rival that of the Caledonian Railway at Grangemouth and aggressively set about acquiring the harbour at Bo’ness. The Harbour Trustees were no match for its plotting. In March 1873 the clerk of the Harbour Trustees noted a discrepancy in the Bill introduced by the NBR whereby the 29th section instead of lending £15,000, it stated that only £5,000 remains to be borrowed by the Trustees, and that £10,000 had already been paid to them. This was not true (Falkirk Herald 13 March 1873, 5) and was merely the first in a series of manipulative manoeuvres. The NBR had spent money on cranes and turntables, but that was meant to be on their own account. Likewise, the Harbour Trustees had rebuilt the south wall across the former slip and placed a new sluice pipe into it, though now there was no reservoir. Mr Drysdale had the contract for that work which was supervised by Alexander Black of Falkirk. The £15,000 to be borrowed by the Harbour Trustees was for extending the east and west piers.

The provision and maintenance of the public promenade to the west of the harbour had been a source of irritation to the NBR for some time and it took the opportunity in the new Bill to remove it:

“the second parties have applied to Parliament to acquire compulsorily a Promenade at Bo’ness. The first parties hereby agree to alienate the same, and to close the three level crossings over the Railway Station, and they also consent to the second parties acquiring the stripe of foreshore parallel to the existing station; and in consideration thereof, the second parties undertake within fourteen days after the Acts have been sanctioned by Parliament to pay to the first parties such sum, being by way of compensation or otherwise as may be mutually agreed upon.”

It also got its eastern extension

“the second parties having applied in the present session of Parliament for power to extend the railway from Bo’ness Station along the shore to Bridgeness Iron Works, the first parties have consented to the same being carried out as proposed.”

For this the NBR only had to pay a nominal annual payment of £5 for the rent of the ground occupied by its rails and cranes, “so as sufficiently to keep distinct the relations of landlord and tenant, and proprietor and occupant.” The NBR had come out of the arrangement rather well.

The work advanced rapidly, though there was a setback to the Bridgeness Branch in December 1876 when a storm swept away part of its embankment. The violent gale also left its mark on Bo’ness Harbour. The wrecked schooner Zwaantjewina was lifted from where she was lying at the east side of the harbour and carried west about 500yds and dashed up against the piles of the new quay (Falkirk Herald 9 December 1876, 3).

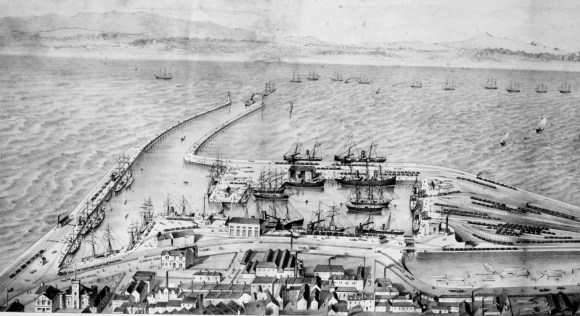

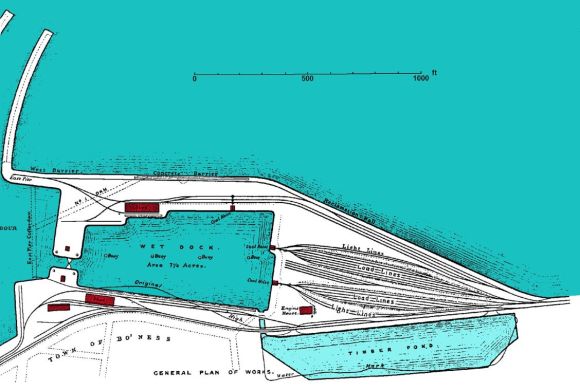

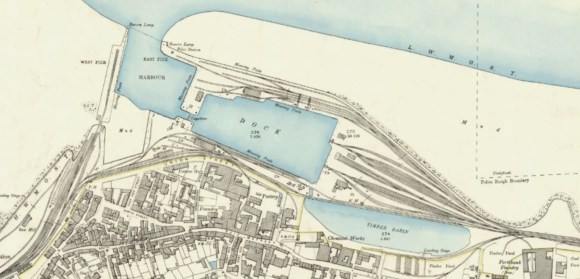

In 1874 the Harbour Trustees asked Thomas Meik & Son of Edinburgh, a well-known firm of civil engineers which specialised in harbours, to prepare plans for a massive expansion of the facilities at Bo’ness. The designs submitted involved the extension of the piers by about 800ft and the construction of a wet dock of four acres on a site to be reclaimed from the sea. The depth of water on the sill was proposed to be 20ft at high water of ordinary spring tides. The estimated cost was put at £75,000 for the work on the piers and £110,000 for the dock. The Trustees resolved to carry out the work.

In 1875 Bo’ness applied to Parliament and obtained the “The Borrowstounness Town and Harbour Improvement Act.” This authorised the deepening of the harbour and the construction of a wet dock. It also incorporated a new body called “The Trustees for the Town and Harbour of Borrowstounness,” with power to manage the harbour and to construct and maintain new works. Only residenters and ratepayers in Bo’ness were eligible for trusteeship. The Harbour Trustees were empowered to borrow on the security of the harbour and its future revenue sums up to £185,000.

Under the provisions of the Act the Trustees borrowed £20,000 from the Public Works Loan Commissioners and £1,200 from a private lender and set about constructing the necessary extension to the piers, parts of which were required to be finished before work on the dock could be commenced. Part of the new East Pier was to act as a cofferdam for the subsequent construction of the dock. The construction of this dam, 300ft in length, about 280ft of the permanent part of the East Pier, and 350ft of the West Pier, occupied the three years from 1876 to 1878. It also included the erection of a steam crane on the West Pier, capable of lifting 25 tons. During this period the Harbour Trustees negotiated for the larger sums required for the dock works.

In 1877 an agreement was made with the NBR by which the town and railway were to share the management of the harbour and dock, and the Company was to advance the additional capital required. The demands of the railway, however, meant that the size of the dock was increased from 4 to 7½ acres, and the depth of water on the sill from 20 to 22 feet at spring tides. This was essential to meet the requirements of the larger ships coming into use. It raised the estimated cost for the dock and reclamation works to £180,000. Another Act of Parliament was required, and “The Borrowstounness Town and Harbour (Amendment) Act, 1878” was passed. By this a new body entitled the “Borrowstounness Harbour Commissioners” was created to manage the harbour. It consisted of eight Commissioners – four representing the town of Bo’ness and four appointed by the North British Railway. The Railway became bound to grant loans to the Commissioners sufficient to carry out the works, not exceeding £185,000. By a subsequent Act of 1880 the Railway was empowered to guarantee interest on any mortgages arranged by the Harbour Commissioners.

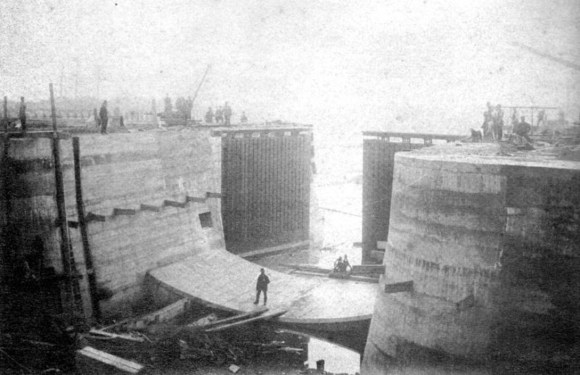

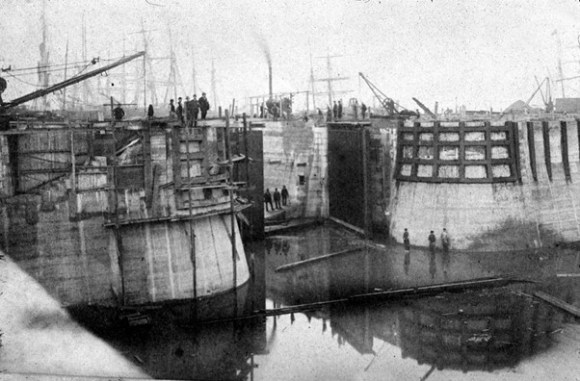

The contract for the dock was let in June 1878 to Thomas S Hunter of Glasgow, and a start was made in September of the same year. The completion date was set at 1 January 1882. Borings were taken over the whole site with the view of choosing the most favourable site for the dock entrance. They showed that the silt was 60-70ft deep below low-water level in some places, and in one spot was even deeper. Near the shore, however, a fine stone-free red clay was found, perfectly watertight and of a constituency like butter. The entrance and the dock walls were therefore founded on that material – whereas the piers were set on the silt or dirty sand.

The cofferdams to enclose the space required for the dock were intended to commence at the end of the east pier and to take the line of the “west barrier” eastward, this being 350ft north of the proposed dock entrance. The line had to be altered to avoid some particularly soft ground revealed by the boring. The clay was at a moderate depth at the site fixed for the entrance but it dipped rapidly to the north and north-west. Consequently, a dam (marked No. 1 Dam on the plan below) was placed on a south-west/north-east orientation on the clay only 170ft from the entrance. The west barrier was then built up and the triangular area between them was filled in to provide extra stability. The seaward faces were covered with whinstone rubble and the dams were backed with burnt shale (blaize) from nearby bings. The eastern end of the West Barrier was part of the cofferdam system, but as it was intended to use it as a timber wharf at the end of the project, it was given a light concrete wall at the face. During the construction work this served as a quay for landing ballast and other materials. Further east this dam gradually decreased in strength, serving as a reclamation wall as well as a dam. Together, the No 1 Dam, the west barrier, the concrete barrier, and the reclamation wall, totalled 2.630ft in length and proved sufficiently watertight to allow the construction of the dock walls and entrance to go ahead, requiring only occasional pumping.

Slag from the Kinneil Ironworks had been used in the concrete for the east pier and the crane foundation on the west pier, but it was not of the right quality for the walls of the dock and entrance. There a superior concrete with a tensile strength of 1,000 lbs on a 2¼ inch section was used. As the expense of bringing suitable materials to the site for the concrete was high, the engineers experimented with local resources. Blocks of concrete were made using broken whinstone from Carlingnose near North Queensferry (8 miles down the Forth) and another set using the shale from the local bings. The shale was burnt till it was red throughout and possessed a high specific gravity, being nearly as heavy as sandstone. The blaize blocks had a handsome appearance and cost half of those using whinstone. The blocks were broken in hydraulic presses and by the application of severe weight. In the newly cast blocks the shale performed best, but after ten months the whinstone was marginally better. This performance was due to the shale being more porous, causing the concrete to set quicker. As the concrete was to be used in a wet environment the quick-setting concrete was an important advantage, given that the dock walls would be at most risk of yielding when in a green state. Accordingly, the concrete adopted for the lower half of the walls and entrance consisted of 7 parts of broken blaize and sand to 1 part of cement. The sand came from Drum Sands, west of Cramond, 9 miles away. In the upper part of the work the necessity for a quick-setting concrete was not so apparent and, on the other hand, it was desirable to have a strong material with a hard skin to stand the chafing of the ships. Consequently at that point broken whinstone was used in place of the blaize. Large stones were placed at the top of each pouring whilst the concrete was still soft so that they would form a bond with the next layer. The layers were 4ft thick and the ends were finished square with a deep groove surrounded by old iron rails and chains to bond the next section. The front of the wall was worked with finer concrete which gave them an appearance of polished ashlar.

The dock walls were built on open timber platforms resting on piles. The piles were 15ft long and 4ft apart, upon which a lattice of beams was set. The level of the bottom of the concrete was normally 8ft below the bottom of the dock, but it was frequently necessary to carry the concrete lower to reach a tolerably solid bed. The foundations were supported by sheet-piles at both the front and back to stop the walls from sliding. The space behind the walls was filled with blaize, ashes, and slag, in 2ft layers as the work progressed. All of the walls were raised to half their height before any part of them was taken higher, thus avoiding cracks caused by settling. They sank by 6 to 8 inches during construction. At the junction of the dock walls with those of the entrance a tapering mortise and tenon joint was employed and the 3ins gap filled with puddle clay. This allowed the two elements to settle at their own rate. The completed dock walls were 19ft wide at the base, 38ft high, and were finished with a granite coping. Timber fenders were embedded in the concrete 6ft apart.

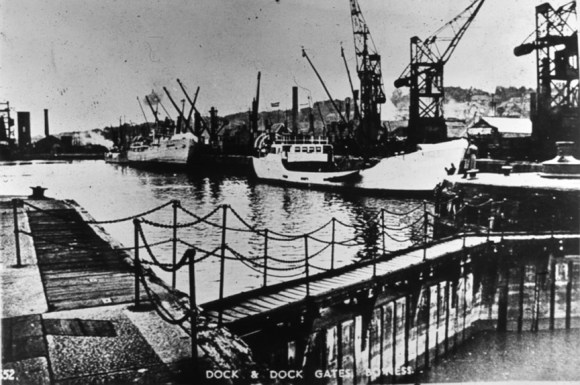

The harbour wall on the approach to the wet dock had to be more substantial because the clay foundation was not as good, and because it did not have the support of a constant head of water. No lock was provided at the entrance, as the single gates could be kept open for about three hours at high water. The entrance channel is 120ft long and its base– the sills and apron – was thicker than normal due to the soft nature of the ground. The sill is 13ft 6ins thick, being 5ft of granite invert, 2ft 6ins of brick in cement, and 6ft of concrete. Cross walls at either end of the apron were even deeper, reaching down 18ft 6ins, with 30ft long piles extending 20ft beyond them. The gates were made of greenheart wood and were worked by hydraulic presses with chains taken round rollers at their fast ends – it took 1½ minutes to open them. Sluices were built into the entrance walls and were opened and closed by four ship capstans.

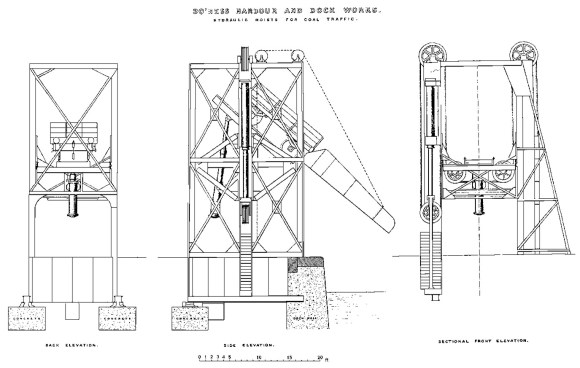

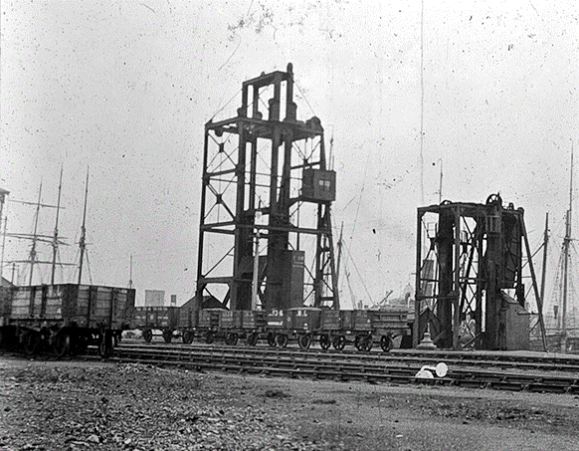

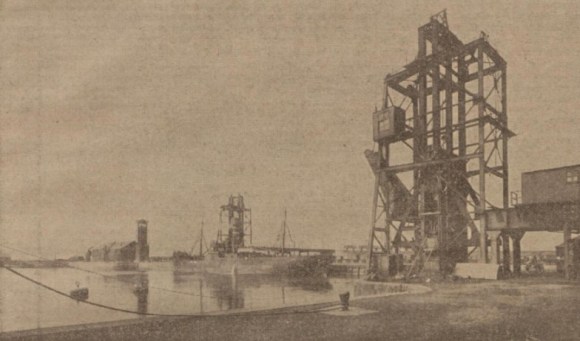

Three huge hydraulic hoists or tips were erected – two on the east wall of the wet dock and one on the north. These low-level hoists were specifically designed so as not to occupy large areas, allowing the quays also to be used for general goods. The large chutes were carried on six steel-wire ropes attached to two hydraulic presses. These took the coal wagons and tipped them end on. The chute or cradle and the wagon weighed about 10 tons and the coal could add up to 12 tons. The railway ran directly to the cradles of the hoists at the east end of the dock; the other hoist required a turntable. However, as the wagons only opened at one end and could, and often did, arrive facing the wrong way, turntables and capstans were provided at all of the hoists. One of the turntables was worked with hydraulics and here four men could ship 20-30 wagons an hour. Each hoist was provided with 1,500 yards of railway sidings so that the loaded coal wagons could be waiting for the ship to arrive.

The other trade at the dock was provided for by portable hydraulic cranes running along the edge of the quays. Capstans were placed round the dock for moving the railway trucks, thus doing away with the need for horses. Sheds were erected for storing general goods, esparto grass and so on. The floor of the general goods shed was on the level of the floor of the railway trucks to aid unloading. Each shed was fitted with a 30cwt hydraulic crane.

Horses were still to be seen at the dock until just after the First World War, but they were few and far between. The main users were the contractors from outside, bringing in materials and provisions. An example of the problems that might arise occurred in June 1912 when a Bo’ness grocer was delivering stores to a ship at the quay. The horse took fright and backed, with the result that it was dragged over the edge of the quay wall into the dock. Freeing itself, the animal swam about, and was eventually rescued. The van and provisions sank (Edinburgh Evening News 24 June 1912, 3).

The power for the hydraulic machinery was provided by a compound engine pumping water at a pressure of 700 lbs per square inch into a steam accumulator. The steam was supplied to the engines and accumulator by two steel boilers of the Cornish type, working at a pressure of 80 lbs per square inch. The engines and accumulator were supplied by Brown Brothers & Company, who also furnished the coal hoists, gate machinery, and some of the cranes and capstans. The shed machinery and the remainder of the capstans and cranes were from the works of the Hydraulic Company of Chester.

The main contractor for the dock, Thomas S Hunter, died in February 1880, and the work was continued by his trustee. The resident engineer was F Jopling and the contractor’s engineer was J L Houston. The dock was opened on 3 December 1881, providing 2,400ft of quayage.

After the official opening of the dock the work on the pier extensions was completed and the timber pond was formed. In August 1882 the construction plant was sold off in consequence of the winding up of the estate of T.S. Hunter, the contractor. The timber pond opened off the south-east corner of the new dock and stretched eastward along the old coastline. The channel between it and the dock passed under two railway bridges which were quite close together. One day in September 1891 a large raft which was being taken to the timber basin became fouled underneath the bridges., Before it could be cleared the tide had risen and jammed the raft so that it could not be moved. As the tide rose higher, the bridges were in danger of being lifted from their foundations. The stone work of one of them cracked, and began to give way, and in order to prevent further damage two engines were procured, which stood on the bridges for several hours, blocking the rail traffic till the tide began to ebb (Dundee Evening Telegraph 21 September 1891, 2).

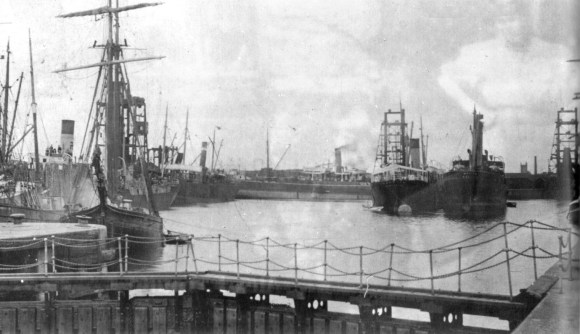

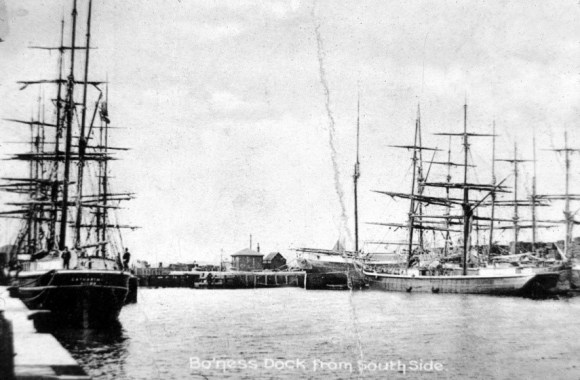

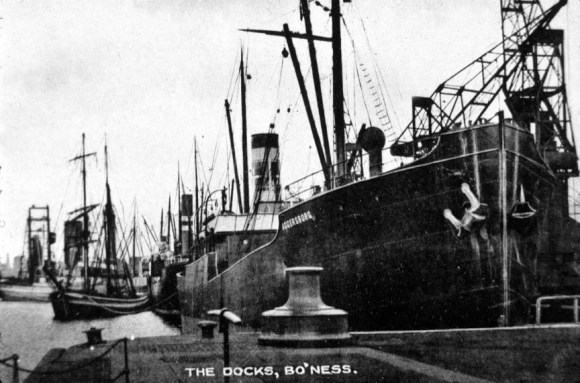

The old harbour now had an area of 5½ acres with quayage of 1,900ft. It was principally used for the accommodation of the large number of sailing vessels still used in connection with the timber trade.

The coal hoists allowed ships to be quickly loaded with cargo and bunker coal, thus reducing demurrage costs and allowing the vessels to return to run their voyages.

Much was made of the speed of loading. For example, the steamer Newbattle of Leith arrived in Bo’ness Dock on a Saturday in May 1885 and commenced to load at 2.30pm, and was finished at midnight, having shipped 1,180 tons of coal in 9½ hours. She arrived on one tide and sailed the next (Edinburgh Evening News 4 May 1885, 3). To make things even quicker, one of the dock contractors invented an automatic tipping scoop. This came into use in 1887 and was highly successful. He was able to patent it and three were despatched to Greenock Dock in 1889. Working late at night to load the vessels required better lighting and so in 1890 it was decided to introduce electric lighting, though it was early in 1898 before this was achieved.

Ships were increasing in size at a rapid rate, making them more economic. On 13 July 1885 the SS Anerley berthed at Bo’ness. She was the largest vessel ever to visit the port, and indeed with a draft of 21ft 4ins almost the largest that could get in. Her cargo consists of 2,200 tons of phosphate rock. As the ships got larger, so too did the handling facilities. In 1891 a much larger coal hoist was erected on the north side of the dock by Armstrong, Mitchell, & Co of Newcastle, capable of lifting 25 feet. In January 1894, it was able to commence loading the Danish steamer Carl Hecksher of Copenhagen and completed her full complement of about 2200 tons cargo and bunker coal within 20 hours. One of the two hoists at the east end of the dock was replaced with a similar hoist. These worked on hydraulics, and in August 1891 a new hydraulic engine was put into commission. It too was by Armstrong, Mitchell & Co. The 150 horse-power engine was a high pressure one, with direct acting pumps, capable of pumping water at a pressure of 850 lb to the square inch.

In the summer of 1886 the Bo’ness Dock Commissioners gave notice that only pilots licensed by them would have the right of pilotage within the harbour of Bo’ness and a pilots’ house was subsequently built near the head of the East Pier. At this time there were many complaints from those working in the harbour and dock area that in getting to work they had to cross several railway lines which were busy with shunting trains. The Town Trustees joined the campaign to have a footbridge placed over these lines and its representatives on the Dock Commission were also in favour. By this stage it had become apparent that these particular commissioners had little say in the running of the dock and that the important decisions were being taken by the Railway Company. The NBR sent an engineer to survey the entry points, raising hopes that the bridge would be built in due course. Instead the NBR appointed a gatesman in 1891 to keep the main crossing clear. The debate got rather heated with the town saying that it would take a death for the Railway Company to improve safety! It was wrong, for in August 1892 a carter from Grangepans, named Lawrence Scotland, was killed at the level-crossing by a shunting train and his boy assistant, who was on the cart, had a narrow escape. No bridge was forthcoming. Even worse, the gatesman, Henry McKillop, who was a young boy, was killed at the level crossing on 19 September 1896. His father took the Company to court and it turned out that the driver’s view of the crossing was obscured by a water tank, meaning that the Company was culpable and had to pay compensation.

By 1892 the Bo’ness Dock Commission was in a financial crisis as a result of the huge borrowing for the construction of the wet dock and suggestions were made that the NBR should take full possession of the Dock. This situation was considerably exacerbated by the interest payments on the loan from the NBR. These had been set by the Act of Parliament at the high rate of 5%, and each year the arrears were added to the total amount for which interest was chargeable. The income derived from duties at the dock only paid off a small fraction of the interest due and so the capital borrowing remained undiminished. At 31 July 1895 the capital expenditure amounted to £275,172 and the unpaid interest to £165,457, a total indebtedness of £440,629. The interest alone payable in 1894 amounted to £22,233. This burden lay principally upon the town of Bo’ness. Not only did the NBR not need to worry about the interest (£165,457) because it was the lender, it also had the security of the harbour and dock. The longer it waited, the better the terms it was able to extract. In April 1895 it offered to acquire the town’s rights of property in and management of the dock and harbour undertaking, together with the Corbiehall crossing, taking over the whole debt. For this it agreed to pay the burgh £250 per annum, increasing every two years by £50 to £500, which sum was to be continued to be paid in all time thereafter. It also agreed erect a footbridge over the railway at Corbiehall, giving access to the foreshore, the Town to pay a sum not exceeding £10 yearly by way of interest and upkeep. All rights of access to the Harbour for the purposes of business and pleasure possessed by the public, and as hitherto enjoyed by them, were not to be prejudiced or affected, and any claims made by officials of the Harbour Commission whose tenure of office was affected by the transference of the undertakings was to be settled by the Railway Company (a bribe). The town and Commissioners accepted the terms and the NBR acquired Bo’ness Dock and Harbour for the measly sum of £275,172.

During the negotiations the NBR had wanted to introduce a charge for passengers landing at Bo’ness, but it agreed to drop it. The Caledonian Railway opposed the Harbour Transference Bill and asked for running powers. The railway line was a single track and this made the request awkward. Although the right was given, the charges were exorbitant. So, the Caledonian only ran trains for a few months before giving up – the town remained dependent upon the NBR.

The building of the Slip had interfered with the sluicing operations to remove the mud from the harbour and the complete eradication of the reservoir basin only exacerbated the problem. However, the lengthening of the piers would have necessitated the introduction of regular dredging anyway. The Harbour Commissioners acquired a dredger called the “Avon,” but she was seriously damaged in May 1895 by the Glasgow steam River Ettrick at the harbour mouth. Silting was to remain a big problem.

After years of discussion the project to install electric lighting at the dock and harbour was finally pushed forward at the end of 1897. Meek & Son, engineers, Edinburgh, purchased a double engine dynamo and electric plant which had been used in the public library in Edinburgh and forwarded them to Bo’ness. Offers for fitting up and installation for 20 lamps initially were invited and Brush Electrical Engineering Co Ltd of Edinburgh was awarded the contract. It proposed 15 lights of 2000 candle-power each on metal pillars 25ft high mounted in concrete. The workforce considered that this was insufficient and so delegates were sent to Grangemouth and Methil Docks to inspect what had been done there. The first lights were turned on at the end of August 1898. New, more efficient, boilers were installed at the engine house to cope with the extra demand for this and the additional hydraulic cranes about to come on line. Up until this time the dock gates had been opened by capstans on Sundays as the boilers were usually run down that day for religious reasons. Problems with the capstans meant that it was agreed that in future the gates would also be opened and shut by steam on the Lord’s Day.

The NBR had put out tender requests for an additional 30cwt crane at the dock in the summer of 1898, and at the end of August it received five offers, but none could do the work in less than 3 or 4 months. Due to the great demand prices were higher than normal and so the order was delayed. The new hydraulic crane made by Armstrong and Co was erected in November 1899.

Bo’ness Dock and Harbour became the sole property of the North British Railway Company in November 1899. Tariffs were reduced and the port became exceptionally busy resulting in calls for further extensions. The NBR refused to entertain any such proposals and openly concentrated its efforts upon increasing the efficiency of the existing infrastructure. The improvements in the cranes were part of this drive, along with more storage and railway sidings and additional wagons. In fact, the Caledonian Railway Company consciously lowered the incentive for the NBR to put in place an expensive programme of expenditure at Bo’ness by giving it easy running terms at Grangemouth where the docks were being massively expanded.

1904 was a busy year for construction work at the dock. These works included a new high-level hoist, an overhead bridge, hydraulic turntables, and powerful new engines to drive the hydraulic machinery. The hydraulic hoist was said to be one of the largest in Great Britain and was specially designed to suit the new 20-ton wagons then coming into use; giving a tipping rate of over 300 tons in half-an-hour. It was capable of doing four times the work of its predecessor, which was described as a “primitive erection,” even though when it was erected in 1881 it was considered innovative and breaking edge. The cost of the hoist alone was £5,000, and altogether £30,000 was spent on the improvements. That same year the dock was slightly extended at its north-east corner, mainly so that two ships of greater length could use the east wharf for loading with coal. The construction work required the provision of a cofferdam before the old dock wall could be removed and the new one constructed. Part of the foundation of the old wall was left in at the toe of its replacement to ensure that no slippage occurred. It was early in 1905 before the work was complete.

By 1910 there were four coal hoists, three of which had recently been replaced by Tannett, Walker & Co Ltd of Leeds. No. 1, situated on the north side, was the newest and largest, with a lifting capacity of 35 tons; Nos. 3 and 4, on the east side, each had a capacity of 30 tons. To overcome complaints of short weight of coals delivered at foreign ports, weighing machines were provided at the coal hoists in 1909; previously they had relied upon the weight marked on each wagon. There were six portable hydraulic cranes in 1881 for discharging purposes, and this had increased to sixteen by 1912. Twelve were at the Dock and four at the west pier of the Harbour. Six were erected in 1912 by Tannett, Walker & Co Ltd. One of the cranes had a capacity of 2 tons, another of 3 tons, whilst the average capacity of the other 14 cranes was 30 cwts. On the dockside the railway trucks were moved using hydraulic capstans, which were also used to assist vessels entering or leaving the dock.

Timber was the largest of the imports, but esparto grass for the papermaking industry was also brought in in large quantities. This was a difficult cargo as it had a tendency to overheat in transport and could spontaneously combust. The steamer Black Sea arrived in Bo’ness Dock just after Christmas 1885 with her cargo of grass on fire. She was scuttled to put the fire out and raised a week later (Edinburgh Evening News 5 January 1886, 3). A year later, on 21 December 1886, while the steamer Newcastle of Newcastle was discharging esparto grass in Bo’ness Dock, one of the workmen’s lamps exploded in the forehold, which was immediately enveloped in flames.

The fire hose belonging to the dock and to the steamer, after playing on the fire for two hours were of no avail, and the steamer also had to be scuttled in the dock (Edinburgh Evening News 22 December 1886, 2).

In December 1890 a fire gutted the offices of the Custom House at Regent House, destroying the port’s records. The following year a new building in the Scottish Baronial style was erected in Union Street facing the dock. It included a number of dwellings, some of these faced onto Kinneil Street, later appropriately renamed Register Street.

| EXPORTED (Tons) | SHIPPED COASTWISE (Tons) | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1905 | 584,091 | ||

| 1906 | 661,070 | ||

| 1907* | 708,852 | 91,304 | 810,300 (800,156) |

| 1908* | 629,101 | 108,122 | 767,760 (720,405) |

| 1909* | 573,778 | 151,627 | 752,512 (725,405) |

| 1910* | 632,292 | 187,629 | (819,921) |

| 1911* | 591,704 | 158,167 | (749,871) |

| 1912* | 569,260 | 161,517 | (730,777) |

Coal remained the mainstay of Bo’ness Dock. When it opened in 1881 the annual export was only 60,000 tons but this soon increased. Other exports included pig iron, fire bricks, chemical manure and general goods.

The position of Bo’ness in relation to northern Europe for long made it the premier port in Scotland for timber imports. The wood arrived from Russia, Germany, Norway and Sweden in the form of pitwood, railway sleepers, deals and pine battens.

In 1910 most of this was still carried on sailing ships, but they were slowly replaced by steamers, a process speeded up by the First World War.

As much of the wood came from the Baltic, which froze over the winter, the imports were episodic with rushes upon the opening of the sea route in spring and just before its closure in the winter. The timber vessels were accommodated at the harbour and unloaded using moveable hydraulic cranes and placed in wagons pulled by capstans. Two additional powerful cranes were placed at the dock, allowing the old ones to be moved to the West Pier specifically for this trade in 1908. The provision of pit props became particularly associated with Bo’ness which earned it the nickname of “Pitpropolis.” Part of the reason for that was the railway link via the Slamannan Railway to the coalfields in Lanarkshire and beyond.

The boom and bust nature of the trade meant that sometimes there was a scarcity of labour, and sometimes hundreds of men were idle. The increased efficiency of handling at the dockside (there were six new hydraulic cranes at the West Pier in 1912) should have sped up the unloading, but there were occasional problems – notably a shortage of wagons, or the breakdown of the hydraulics, and the odd strike. The statistics speak for themselves:

| HEWN & PITWOOD | SAWN | TOTAL LOADS | VALUE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1905 | 141,925 | 23,523 | 165,448 | |

| 1906 | 147,918 | 21,743 | 169,661 | |

| 1907 | 181,211 | 9,350 | 190,561 | |

| 1908 | 160,027 | 14,089 | 174,116 | |

| 1909 | 115,773 | 8,902 | 124,675 | |

| 1910 | 196,976 | £235,032 | ||

| 1911 | 203,577 | £250,280 | ||

| 1912 | 207,231 | £295,387 |

Other imports in 1910 included esparto grass, iron ore, grain, wood pulp, sulphur ore, and phosphates.

| I — FOREIGN TRADE. | 1907 No. | 1907 TONS | 1911 No. | 1911 TONS | 1912 No. | 1912 TONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessels in with cargo – steam | 165 | 114,809 | 157 | 115,489 | 163 | 116,166 |

| Ditto – sail | 141 | 28,375 | 94 | 18.135 | 59 | 13,137 |

| Ditto in ballast – steam | 361 | 231,775 | 270 | 183,842 | 253 | 168,606 |

| Ditto in ballast – sail | 24 | 3,695 | 51 | 4,905 | 32 | 3,401 |

| Total freight inward | 691 | 378,654 | 572 | 322,371 | 507 | 310,310 |

| Vessels out with cargo – steam | 541 | 328,744 | 428 | 283,943 | 417 | 266,138 |

| Ditto – sail | 197 | 35,603 | 134 | 19.828 | 98 | 16,326 |

| Ditto in ballast – steam | 1 | 1,110 | 8 | 7,726 | 7 | 5,905 |

| Ditto in ballast – sail | — | — | — | — | 1 | 389 |

| Total freight out | 739 | 365,457 | 570 | 311,497 | 523 | 288,758 |

| II – COASTING TRADE | ||||||

| Vessels in with cargo | 142 | 39,742 | 113 | 30,814 | 112 | 31,635 |

| Vessels in in ballast | 374 | 71,753 | 358 | 92,208 | 353 | 103,890 |

| Vessels out with cargo | 462 | 80.894 | 463 | 105.897 | 458 | 107,354 |

| Vessels out in ballast | 96 | 41,473 | 109 | 40,059 | 103 | 49,630 |

| TOTAL VALUE OF IMPORTS | |

|---|---|

| 1907 | £317,449 |

| 1911 | 318,729 |

| 1912 |

In order to accommodate the ever-increasing volume of traffic constantly arriving at Bo’ness Dock the NBR instituted a scheme of foreshore reclamation in 1905. A large quantity of waste material was brought in by rail from the iron and steel works in Lanarkshire. By the end of 1909 an area of over 20 acres of this new land to the east of the dock was leased to traders as storage accommodation. The northern extremity of this reclaimed land became the focus of operations for the Carriden Coal Company in 1910 when it signed a lease with the Crown for the minerals under the Forth to the north and west of Bo’ness, an area of around 900 acres. Bores revealed rich coal seams and so in 1911 a portion of the tidal lands 200 yards east of Bo’ness Dock and 4 acres of foreshore were acquired by that company.

The landward portion was required for the railway sidings and the bit on the coast was for the sinking of a pit shaft; the Main Coal was reached in April 1913. On the Ordnance Survey maps it appears as the “Western Field Colliery” but everyone in Bo’ness knew it simply as the “Dock Pit.”

At the beginning of 1910 the NBR adopted a new rule by which they shut the entrance gates to the dock-head during tidal operations in order to keep the public out. This was resented by a section of the ratepayers, and the matter was taken up by the Town Council. It was found that the public of Bo’ness did have the right to access to the harbour and dock for business and for pleasure, but there were certain limitations, and one of these was that when the gates were open, and vessels passing in and out, the harbour officials required freedom of action in passing and winding ropes about the pier-head without being hampered by people standing about. Indeed, under the bye-laws passed in 1881, power had been given to the harbour authority to turn away trespassers and loiterers from the dock. This was but the beginning of the exclusion of the general public.

The First World War seemed to creep up unnoticed on the traders at Bo’ness with startling speed. In August the movement of pitwood was severely curtailed as ships found it harder and harder to get insurance. A German schooner at Bridgeness was caught by surprise by the outbreak of war and was seized and towed to Bo’ness dock to sail under a British flag. Then, on 25 November disaster – the port was closed by the Government. The pilots assisted in taking away the twenty steamers lying in the roads and disembarked at May Island, where they were to be stationed for the duration. No more ships were to use the dock for four years, except the odd one requiring bunker coal – and then only in exceptional circumstances, such as the secrecy surrounding Q-ships. All goods – in or out – had to go to Leith or Granton by rail. Dockers, hoist drivers, crane operators, stevedores and all the other associated tradesmen were either transported daily to the ports further east, or left for good. Shops suffered.

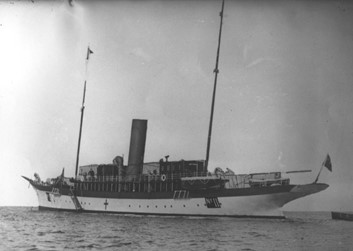

To help to compensate for the closure of the dock and harbour, the Government issued contracts to local firms. The timber yards turned out hundreds of huts – the timber brought in by rail at its expense. A massive horseshoe factory was begun at the old Seaview Foundry by Cochrane Brothers, employing over 200 men! Before the war most shoes had been produced in Germany. The number of vessels using the port was miniscule. One that attracted some attention was the yacht Sheelah belonging to Admiral Beatty. In 1914 her service had been given free by Lady Beatty, in whose name she was registered, for use as a hospital ship. She was fully equipped at Lady Beatty’s expense and was designated “Hospital Ship No.11” and stationed at South Queensferry. Officially she served as a hospital ship from August 1914 until February 1919, but she was actually only used for two years before lying idle at Bo’ness until the end of the war.

The return to normality at the end of the war was just as stretched out as had been the commencement of hostilities. Late in December 1918 the Bo’ness traders were notified by the Commander-in-Chief, Coast of Scotland, that there was no objection to merchant ships using the port of Bo’ness, subject to the same rules being observed as those he had recently introduced for Grangemouth. Incredibly there were still some Government restrictions in September 1919.

Grangemouth had been extensively used during the war for shipbuilding, the refitting and provision of the famous Q-ships, the fitting of paravanes to merchant ships, the assembly and storage of sea mines, and the laying of the massive minefield known as the Northern barrage. Not only had the channel from the docks to the Forth at Grangemouth been continuously dredged during the war, it had been made deeper, with the help of the Bo’ness dredger. Dredging operations at Bo’ness had ceased, with the result that the port was seriously silted up, permitting only vessels of light draught to enter.

The dock of 1881 was designed to accommodate vessels up to 2,000 tons, but two-thirds of the ships of that size had been sunk by enemy action, and their replacements were larger. The Bo’ness traders petitioned the North British Railway Company for an entirely new entrance capable of accommodating vessels of from 3,000 to 4,000 tons deadweight. It was pointed out that in the coal export trade a steamer sailing with, say, 6in or 12ins short of her loaded draught represented the difference between a profit and loss to the shipowner, who naturally would favour Grangemouth or Leith where the steamer could be loaded to its full capacity without any fear of a shortage of water. The railway company engineers visited the dock. In November 1919 they estimated the cost of enlarging the entrance as £150,000 and so the Ministry of Transport was asked to contribute as part of the compensation for the wartime closure. At the time, the NBR was involved in a £750,000 expansion of Methil Docks and had little commitment to Bo’ness. The Ministry of Transport was not prepared to contribute such a large sum and restated its position, which was that it was prepared to restore the dock and harbour to its pre-war condition – which simply meant dredging. In April 1920 it was reported that 2 hours of dredging was being done each day, but was not making much headway and there remained 5ft of mud.

On 1 July 1920 the surrendered German steamer Franz Dahl, 1213 registered tonnage, arrived in the dock to be reconditioned by Cochrane Brothers to meet the requirements of the Board of Trade, after which she passed into the hands of the Glen Line, to whom she had been allocated by the British Government. Slowly trade at the dock displayed signs of recovery. Coal exports began as a small fraction of pre-war years and were not helped by intermittent strikes of miners, dockers and railwaymen. In 1921 during a long coal strike 1,000 tons of coal from the Sahr Valley, Germany, were actually imported to Bo’ness for the Glasgow Corporation. 1925-27 also saw coal imports. Such was their scale and regularity that both Denholm & Co and Harrower, Welsh & Co bought Priestman grabs which were capable of discharging 450 tons in eight hours.

| YEAR | COAL EXPORTS (ton) |

|---|---|

| 1911 | (749,871) |

| 1912 | (730,777) |

| 1920 | 49,098 |

| 1921 | 65,173 |

| 1922 | 513,393 |

| 1924 | 260,827 |

| 1931 | 185,744 |

| 1932 | 238,809 |

| 1933 | 406,938 |

| 1934 | 484,731 |

| 1936 | 385,979 |

| 1937 | 375,441 |

Initially, the export trade at Bo’ness Dock was helped by the scrap steel sent to Germany from the shipbreaking yard at Bridgeness. However, by the late 1920s steel for Motherwell was being imported by four steamers – Charles, Marcel, Rosa and Yvonne. Scrap metal seemed to be going through Grangemouth, as was also the case with esparto grass.

In 1923 the London North Eastern Railway took over from the North British Railway and the merchants of Bo’ness took the opportunity to lay before it the need for an enlargement of the wet dock. After investigating, the LNER Board in January 1930 ruled out an extension, which was costed at about £1 million. It was still considering the less costly scheme of enlarging the dock gate. That year the herrings reappeared in the Forth and for a short spell there was a small herring market on the harbour quay selling some 20 boxes a day to Glasgow firms – not enough to justify additional structures.

So, in April the proposed new entrance was turned down – it would have required the closing of the dock for 18 months and during that time the trade would have diverted elsewhere. A part of the docklands was then used by the LNER as a new sleeper yard. The old yard at Corbiehall was moved to the east of the dock and a vast stock of sleepers, over 200,000, were brought in. New creosoting plant was installed. The adjacent timber basin was drained.

In 1931 there were 347 arrivals at the port with an aggregate tonnage of 195,267; and in 1932 this was 346 arrivals with a tonnage of 219,073. With such low rates of usage the port was barely breaking even and in 1933 the LNER claimed to be losing £8,000 a year on Bo’ness Dock. The greatest difficulties it faced was the continuous need for dredging of the bank outside the dock, and the small size of the entrance. It therefore proposed to increase the dues.

Trade was already slowing down when the Second World War began. Preparations for hostilities had been going on for some time and a large concrete air raid shelter, capable of holding far more than the 50-60 men likely to be in the area, was completed at the eastern coal hoists just weeks before war broke out. Once again the Government closed the dock to commercial traffic for the duration of the war. This time, however, it was given an important wartime role and became the home of HMS Stopford – a base used to train the crews of landing craft for the invasion of France. It was also used for fitting out the motor torpedo boats fabricated nearby at Bridgeness (Bailey 2013). The rights of way into and through the dock were closed under the Emergency Powers Act.

The perimeter fence was renewed and guards were placed at the entrances, latterly manned by the Home Guard (Bailey 2008). Enamelled badges inscribed “B/ D & H” were issued to those working in the restricted area which, with an identity card bearing a photograph, gave entry. The initials stood for Bo’ness Dock & Harbour. One of those gaining entry was Mrs Cameron who tended to the electrical plant, one of several women taking over a job previously only done by men.

Two cranes were removed from the north quay of the dock for use elsewhere – and never returned. Home grown timber replaced that previously imported from the Baltic.

With the return to peace in 1945, dredging recommenced, though once again the mud had taken a strong hold. The Germans returned in March 1947 – bringing pitwood as part of the war reparations. The crew was somewhat surprised to find a friendly welcome! An incident in 1949 typifies the problems that Bo’ness now faced. That October the Werner II of 764 tons crashed into the West Pier demolishing about 50ft of the wooden structure and coming to rest on the concrete foundations. Only small vessels, such as this one, were able to use the port and there had been a heavy running tide at the time. She was eventually pulled off by two tugs which had to come all of the way from Grangemouth.

In 1948 the Labour Government established the nationally-owned British Transport Commission to take over the four large private railways, including the LNER. Their assets included 32 ports of which Bo’ness was one. After examining the facilities at Bo’ness it decided in 1955 to replace the obsolete steam engines which powered the hydraulic system with electricity powered machinery. The operating costs were significantly less, justifying the expenditure of £25,000. Repairs were made to the timber jetties, and at the entrance to the harbour a dangerous old pier was removed and replaced by two wooden dolphins – the cost of these being £5,000. The dredging operations were improved. Derelict buildings on the dock property were removed. Things looked set for the future.

There had been a collapse of coal exports and a sharp decline in the tonnages of imported pit props, and by 1954 trade had reached a very low level. Of six firms who imported these cargoes only two still handled stock locally. The local shipping firms were then relying on imports of fertilisers, cement clinker, scrap metal, and other materials which in pre-war years had constituted a very small proportion of their trade. In 1956 only 183 ships docked at Bo’ness delivering imports of 151,000 tons and taking away 11,000 tons of exports. It should therefore have come as no surprise when, in November 1957, the Docks Manager for East Coast Scottish Ports, James Newman, proposed the closure of Bo’ness Dock. In a circular letter addressed to local authorities, shipping interests and trade unions, he stated that over the past ten years there had been a deficit of £292,951 and that the volume of shipping was too small.

An attempt to transfer some of the dock equipment to Grangemouth in 1954 had been blocked by local opposition and so the town council, the local traders and the unions got together to stop the closure decision. Questions were asked in Parliament and there were lots of meetings, discussions, reports and delays. After all of that, the British Transport Commission decided that it would indeed close Bo’ness Dock with effect from the end of 1958. Not even the increased coal production at Kinneil could save it – practically all of its coal went to the steel mills in Lanarkshire and although it used the dock for importing pit props, these could be brought by road from Grangemouth. As if to show that this decision was justified, the motor vessel Johannes Schup of Hamburg spent five days outside of the dock that October waiting for there to be sufficient depth of water to enter with a cargo of pit props.

Late on the evening of 24 June 1959 a large crowd turned out to see the departure of the last ship from the dock. Appropriately, she was a Dutch vessel, the Monadisch of Groningen, and was gaily beflagged from stem to stern. After a 19 month campaign to keep it open, Bo’ness Dock officially closed on 30 June 1959. The permanent dock staff of 15 men, together with 82 registered dockers, and a few railway workers were redeployed. The dockers were transferred to Grangemouth, though they remained as a separate section, meaning that the work preference was given to Grangemouth men. The Bo’ness men could therefore only rely on the national minimum guaranteed by the National Dock Labour Board – £6 12s a week. However, trade at Grangemouth soon increased and they became fully employed. The Bo’ness traders were given reduced rates in sending their goods to Grangemouth.

| HARBOURMASTERS | |

|---|---|

| 1881-1901 | Captain Ainslie |

| c1896-1908 | Angus McIntosh |

| 1908- | Cairns |

| -1935 | Robert Smith |

| 1935-1959 | James McKelvie |

Almost immediately the dismantling work began. Some machinery was transferred to other ports, and much was cut up for scrap. The dock did not give up without a fight and on 5 February 1960 two workmen involved in the work narrowly escaped with their lives. The brakes on their diesel-driven 20-ton mobile crane failed and they jumped out just before it plunged into 20ft of water.

In the late 1970s the Scottish Railway Preservation Society, with the help of Central Regional Council, created a steam railway centre a little to the south-east of the 1881 dock. The area around the dock was landscaped by the Council and a network of paths was created. This was quite a reversal of the previous decades of ever-increasing restrictions of access. Plans were then mooted for the reconstruction of a historic township and to have heritage craft at the dock. This was too ambitious and the plans were never realised. The southern end of the harbour was filled in and the sloping end consolidated with large rocks. This moved the water’s edge even further from the town, providing space for a road, car parks, and recreational land. The West Pier was deteriorating rapidly and so in the late 1980s Falkirk District Council had it clad with new concrete faces.

A stir was made in 2007 when the banking giant ING drew up plans for a superior housing development which included houses placed on stilts in the water. The £175 million plan scheme was abandoned due to the 2008 financial crash. Falkirk Council now maintains the site. Around 2003 a “cofferdam” was placed at the entrance in order to maintain the water levels in the dock – hiding the unsightly and dangerous mud. The impounded water helps to support the dock walls. Dew Piling Ltd of Oldham put in a temporary cofferdam for this work which allowed the silt on the sill to be cleared and 2m of concrete to be cast in situ. From time to time, pleasure craft still visit the outer harbour.

Sites and Monuments Record

| Bo’ness Dock and Harbour | SMR 377 | NS 9994 8195 |

| Bo’ness Harbour Slip | SMR 1267 | NS 9987 8177 |

| Custom House, 8-18 Union Street, Bo’ness | SMR 378 | NS 9997 8179 |

| Douglas Hotel | SMR 1266 | NS 9990 8172 |

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 2008 | Hard as Nails: The Home Guard in Falkirk District. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 2013 | The Forth Front; Falkirk District’s Maritime Contribution to World War II. |

| Bowman, I.A. | Unpublished | Shipbuilding in the Falkirk District. |

| Salmon, T.J. | 1913 | Borrowstounness and District. |