The discovery at Harbour Road in Bridgeness of a stone voussoir from a Roman bathhouse suggests that the shallow bay to the east of Windmill Hill was used by the Roman army as a landing place for its heavier cargoes being delivered for the construction of the nearby fort at Carriden (Bailey 2021, 195). This same spot may then have been used at the end of the Roman occupation to remove material which was to be salved for reuse elsewhere. Amongst this would have been the so-called “Bridgeness Tablet” which was found nearby. It was abandoned before it could be placed on a vessel, carefully concealed so that it did not fall into enemy hands.

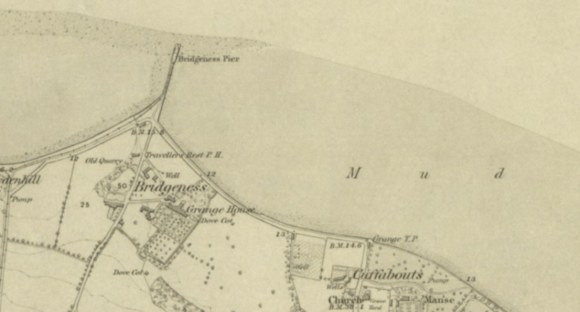

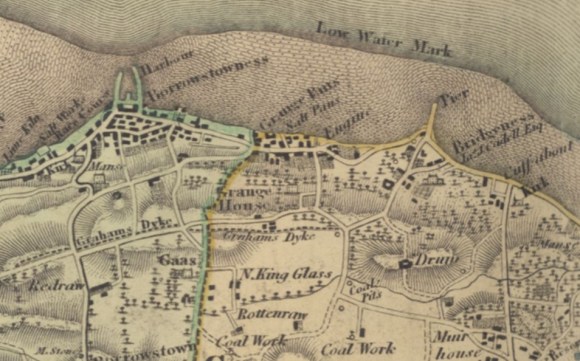

Under a charter of 1615 from James VI, the Grange estate to the east of Bo’ness was erected into a barony with the right of a free port or ports. The obvious location for such a facility would have been the promontory or ness at Bridgeness. Roy’s map of 1755 shows a sea wall fronting this jutting out piece of land which may have been used as a wharf, but the buildings were set well away, with the coastal road running along the south side of the windmill. Further west was the larger settlement of Grangepans with its salt pans and here it seems that the sloping foreshore was used to beach small vessels which conducted trade in all manner of items. Coal and salt had been exported overseas from Carriden for some time but it was only in 1770 that the proprietors of Grange, William and John Cadell, erected a 110yd long pier projecting out from the promontory at Bridgeness. In 1771 part of the water from the nearby mill lade was taken so that it could be used to scour out the harbour (Cadell Papers). In April that year the outer end had to be rebuilt by the Grange Coal Company following storm damage. The work was carried out by John Handyside, mason in Carronshore, the following year (ibid). At first it was often referred to as “the pier and harbour of Grangepans” (eg. Edinburgh Evening Courant 26 December 1785, 1). It is shown on Forrest’s map of 1818 along with the new road infrastructure, which includes Harbour Road, to bring coal from the hill to the south.

Carron Company took a 30 year lease of the ironstone on the Grange estate from 1771 to 1801 with the intention of working 1,000 tons a year for a royalty of £40, or about 1½d per ton. The ironstone was to be shipped at Bridgeness and sent to Carronshore for onwards transport to the Carron Works. However, it does not appear that much ironstone was actually worked at this time.

The right to use the harbour was considered an important part of the value of the Grange estate and featured prominently in its sale in 1777:

“The Lands and Estate of Grange Phillipstone with the town thereof, and manor-place of Grange, and coal, salt works, and iron-stone or iron-ore in the said estate; together with the Teinds. The lands are erected into a free barony, with the liberty and privilege of a harbour at that part of the estate called Bridgeness; and the proprietor has right to the tolls, customs, and duties of the said harbour. The lands lie within the parish of Carriden and sheriffdom of Linlithgow, near to the town of Borrowstounness, and are commodiously situated for shipping the coal at said harbour of Bridgeness…”

(Caledonian Mercury 27 December 1777, 4).

The first statistical account of the parish, written in the early 1790s, noted that coal was exported to London, to the north-most parts of Scotland, to Holland, Germany, and the Baltic. The amounts involved are indicated for Grange Colliery – 6,137 tons of great coal annually, 2,380 of chows and 600 of culm. The quantities from a second colliery in the parish were considered to have been even greater. The nature of shipping was changing:

“Most of the shipping that is now in Borrowstounness formerly belonged to Grangepans: But, since a good pier and harbour was erected in Borrowstounness, most of the ships lie there.”

All of the coal was conveyed down to the harbour in little carts holding about 10cwts and shipped in small sloops. The original pier was exposed and unsheltered and so in December 1773 it was proposed to construct an elementary breakwater on the west side made of wood 40 yards from the pier which might ultimately be used as an additional pier. The sloops of the 18th century sailing up the east coast of Scotland and across the North Sea to Holland and Germany were less than 100 tons in capacity. In 1828 the pier was extended to low water mark by James John Cadell of Grange to suit the larger vessels – brigs and schooners with two masts – that began to displace the sloops. The 120ft addition was broader than the original.

| DATE | SHIP | MASTER |

|---|---|---|

| June 1833 | Curlew | Mill |

| July 1834 | Diana | Innes |

| January 1835 | Trafalgar | Frentz |

| July 1835 | Aurora | Frentz |

| October 1835 | David | Allen |

| June 1837 | Sunderland Halfe | Schloer |

| June 1837 | Stettin Packet | Baumann |

| August 1837 | Wilhelm | Gottschalk |

| September 1837 | Ohlfahrt | Purst |

| October 1837 | Nordstern | Herwig |

| October 1838 | Louise | Sievert |

| June 1840 | Vigilant | Ricks |

| July 1840 | Land | Von Doering |

| January 1841 | Margaret | Forsyth |

| May 1841 | Harry | Klein |

| May 1841 | Lord Dalmeny | Duncanson |

| May 1841 | Henricas | Rieke |

| June 1841 | Paskewitch | Kraft |

| June 1841 | Concordia | Kronenoan |

| June 1841 | Catherina | Juister |

| July 1841 | Brisk | Jewett |

| August 1841 | Success | Myles |

| August 1841 | Catherine | Wilhemine |

| September 1841 | Backhus d’Alida | Stuinnan |

| October 1841 | Astrea | Moller |

| October 1841 | Ostee | Trettin |

| October 1841 | Vrouw Chrstine | Bringeman |

| March 1842 | Wilhelm | Wiencke |

| March 1842 | Ostee | Trettin |

| March 1842 | Paul | Pust |

| April 1842 | Ann | Moir |

| May 1842 | Jessie | Davidson |

| June 1842 | James Walls | Gowie |

| June 1842 | Elizabeth Facet | McRuvie |

| June 1842 | Johanna | Hartwig |

| June 1842 | Caroline | Zaag |

| June 1842 | Maria | Hunger |

| June 1842 | Rebekah | Stevens |

| June 1842 | Venus | Mearns |

| July 1842 | Joseph | Greig |

| July 1842 | Pursuit | Burnet |

| September 1842 | Courier | Witt |

| September 1842 | Caroline | Zaag |

| October 1842 | Hugo | Binder |

| October 1842 | Gottschalk Nordstern | Herwig |

| October 1842 | Heinrich | Brandt |

| December 1842 | Heinrich | Brandt |

Most of the ships calling at Bridgeness in the first half of the 19th century were foreign. With relatively primitive loading methods, and a desire to preserve the Great Coal in large chunks, it could take several days to fill a vessel. The nearby “Travellers Rest” public house catered for them. From 1837 to its closure in 1872 it was run by Elizabeth Nimmo.

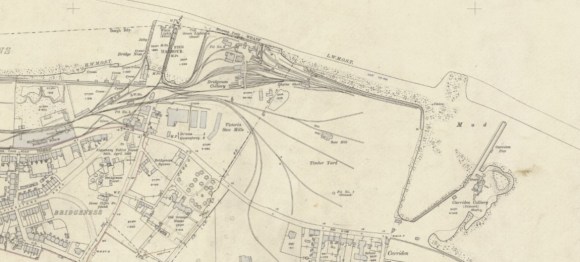

In the late 1840s it was decided to extend the Slamannan Railway to Bo’ness to give access to the harbour there. Cadell tried to get the lead body, the Monklands Railway Company, to take it all the way through to the harbour at Bridgeness, but was unsuccessful. Indeed, initially it actually finished shy of the harbour at Bo’ness. All of the ironstone and coal from Grange that had to go inland had to be carted laboriously to the railway wagons at Bo’ness, and it was not till 1878 that the North British Railway Company agreed to extend the line to Bridgeness.

The colliery at Grange had a chequered career but by the 1860s it was very productive. Calcined iron ore was shipped via Bo’ness Dock and coal continued to flow from the harbour at Bridgeness. Parrot coal was shipped to Arbroath and other east coast ports for gas making – Grange coal was rich in the gassy constituents.

Around 1843 James John Cadell constructed a self-acting railway incline about 560 yards long, from the shore west of the harbour to the high ground south of Meldrum Pit 150ft above the low level at No 4 Pit. This was called “The Run,” and the loaded wagons, three at a time, holding about 2 tons each, were hooked onto a rope passing round a large wooden horizontal pulley with a break strap round it. As they descended they pulled up the empty ones to the level railway at the top. From the bottom the wagons went along a railway that followed the coast to the end of the pier. The Run was no longer required after the ironstone in the Acre Pit was exhausted, about 1875. By this time most of the coal was being worked from pits on the foreshore.

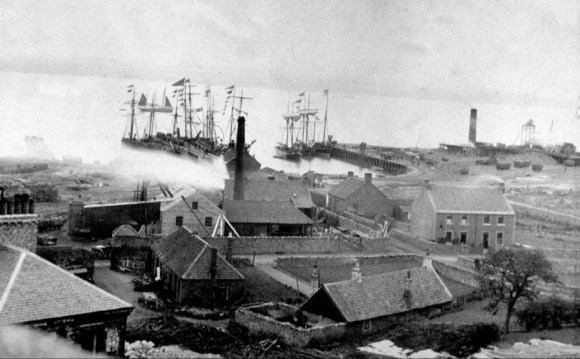

Before 1860 Bridgeness Harbour consisted of a single pier with a rough breakwater on the west side only. In 1862 the old breakwater on the west side, which had become very dilapidated, was rebuilt with stone by William Cadell. About the same time he ran out a straight bank of colliery redd to low water line to form a second and better breakwater on the east side. At this time the local rifle volunteers set up a target and rifle range on the new promontory. A few years later, in 1868, William Cadell bought the foreshore rights to either side of the harbour from the Crown and slowly started the process of reclaiming the mudflats.

Despite the industrial nature of the harbour at Bridgeness it was used as a swimming resort by the locals, particularly the youth. It was here that from the late 1860s a regatta was held as the concluding event of the Grange miners’ fair. These were later replaced by annual trips from the pier along the Forth to places like Aberdour.

Harbour fees at Bridgeness were lower than most of those in neighbouring havens and so quite a number of vessels that were accidentally damaged in this area of the Forth sought sanctuary there. Emergency repairs would then be undertaken and the vessel would make for their home port for the major work.

During 1869 the North British Railway Company and the Trustees of Bo’ness Harbour negotiated for the railway to be extended eastwards from the railway station to serve the East Pier of that harbour. It re-opened the prospect of a future extension to Bridgeness and this was included in the Parliamentary Bill of 1874. In anticipation of this move, William Cadell had sold his rights to the foreshore to the east of Bo’ness harbour, stipulating that any land reclamation there should not interfere with the currents that kept his own harbour relatively free of silt. An agreement between the parties concerned limited the range of goods that would be taken over the Bridgeness Branch. Construction work was set back in December 1876 when a large section of newly built embankment was washed away in a storm.

H M Cadell improved the old pier in 1889-1890. It was too low and was submerged at extreme spring tides. He raised it 3-5 ft and put up a new loading hoist on the east side. The stone for the work was mainly got by excavating the old part next to the shore that had become buried over the years. He also cut a gap in the pier and made a bridge over it to let the ebb tide run through opposite a corresponding gap in the break water that his father had found useful for preventing siltation. Before doing the work he had got an estimate of the probable cost from D & G Stevenson, the well-known harbour engineers. Their figure was £1,480 for the heightening, but by doing the work himself and contracting some of the heavy work out he was able to get it done for £480. This included about £40 for heavy granite blocks for coping at the end of the pier, which had been left over when Bo’ness Dock was built in 1881 and which he bought to finish the job.

A new wharf extended eastwards, adjoining No. 6 Pit, where previously the old “redd bing” had been faced with a rough sea wall. A large number of pitch pine piles were bought from the staging that had been used in the construction of the south end of the Forth Bridge. The piles had been in the water for several years and were considerably wasted by barnacles, but the longest part had been driven deeply into the mud which protected them.

The piles were turned upside down and the worn ends driven into the mud, leaving the formerly buried end upmost to form a pier. This part of the work was supervised by a Mr Burn and was begun on 22 April 1890, when the first pile was driven, and completed on 18 August, when a cargo of pitwood was discharged upon it. The wharf had 118 piles and was 300 ft long. The planking for the top and half timber for the walling were got by spitting up the best of the piles. D & J Stevenson had estimated the cost at £2,700, but the sum paid for the timber and the piling contractor came to just over £1,600. Just as the project was nearing completion, Mr Stupart, who had been the harbour master at Bridgeness for over twenty years, died. He was replaced by James Williamson.

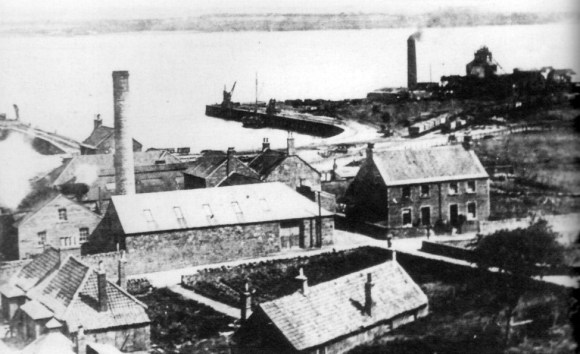

Coal shipping was very brisk all that summer and sometimes as many as a dozen ships were loading or waiting their turn. At that time nearly all were sailing ships, chiefly schooners. Steamers were only occasional visitors at Bridgeness. The appearance of the harbour and colliery can be judged from the photograph taken from the top of Bridgeness Tower in 1892. This was during a strike by the coal miners in the northeast of England.

One of those occasional steamers was the Ecossaise. Whilst at Bridgeness it was hauled up for the purpose of being cleaned and repaired. One of those working on her was a young engineer called Charles Law. He was returning from his work about 11 o’clock one night in August 1891 when he was met by Constable Fullarton. As the young man was carrying a basket the suspicions of the constable were aroused, and he demanded to know what the basket contained. On search being made, it was found to contain about 21½ lbs of tobacco. Fullarton was taken to the police office and locked up. At court he subsequently pled guilty to the charge of smuggling and was fined £1, with 6s 6d of expenses (Falkirk Herald 15 August 1891, 6).

In 1892 rules of pilotage were drawn up for Bo’ness and Bridgeness. H M Cadell wanted the agreement of 1875 between the railway company and the Bo’ness Harbour Commissioners to be dropped and shore dues for goods shipped and unshipped at Bridgeness harbour to be paid to him, failing which he suggested that the Commissioners should lease Bridgeness Harbour. Bridgeness had been operated as a private harbour and its working practices would have to have been brought into line. One immediately obvious discrepancy was its policy regarding infectious diseases. 1892 saw cholera on the Continent and a vessel arrived at Bridgeness from Hamburg for coal without any checks. Fortunately, Hamburg was free of the epidemic at that time.

Unlike most ports, vessels arriving at Bridgeness were allowed to unload their ballast there free of charge. This was then used in the land reclamation to the east. A German ship, the Freda, took advantage of this in the late 1890s, making many trips.

Further improvements came in 1901/2. They were partly necessary on account of the congestion that then took place in the summer traffic at Bo’ness Dock, where about two-thirds of the increased amount of coal raised at Bridgeness Colliery had recently been shipped. About £2,000 was spent on the wharf and a high-loading chute for railway trucks. The wharf was extended 400 feet eastwards at or near the low-water level of ordinary spring tides, which rose and fell about 18ft here. It too was made of pitch pine piles, 40ft long driven in by the contractor, Mr Peattie. The outer piles were 8 feet apart with sheet-piles between. The object of the sheet-piling was to enable the foreshore outside to be dredged down, so that the tide would never leave the foot of the piles. It was thought that as the tidal current ran in the same direction as the wharf, it would never become silted up. The timber work was backed by a high sea wall of stone and concrete that had been built 20 years before to protect the embankment round the colliery – the pit having originally been sunk out in the sea at the end of a long mole reaching nearly to low-water mark.

The original idea had been to put up a haulage engine at the high-level tip and construct a sloping line from the east for the loaded trucks to come up. The empties were to run back westwards by a gentle sloping incline parallel with the wharf. A better plan was followed, by which the trucks were pushed up by a small locomotive and engine that had been purchased by the colliery to take the place of horses hitherto in use. The loco was found to be able to push three or four wagons up at a time and this plan worked well. The new wagons each had a capacity of 6-10 tons, whereas the old ones only held 3cwt.

An idea of the amount of coal being dealt with comes from a short newspaper report that says that in the first week in August 1901 some 512 tons of coal were shipped from Bridgeness – a decrease of 34 tons on the previous week. The total so far that year had been 15,912 tons, compared with 9,887 tons in 1900 (Falkirk Herald 7 August 1901, 6).

It soon became necessary to do some dredging for a berth for larger ships at the wharf. Hiring a dredger was an expensive operation and so H M Cadell bought a small Priestman dredger on a barge with 30 square iron boxes of about a cubic yard capacity each, into which the dredgings were dropped. A 4-ton travelling crane was also got for £100 to lift the mud boxes and tip them into wagons on the wharf side. Ten tip wagons were obtained for £175 from the Grangemouth Dock contractors, and the dredgings were taken by them and tipped into the reclamation basin east of the colliery, so that all the mud was used to help to fill it up and not dropped into the sea as had hitherto been the usual way of disposing of all dredgings. The total cost of the dredging appliances was £825, but all these harbour improvements from 1900 till 1902 cost a total of about £4,330. The new berth was deepened so that there was a depth of about 3ft at low tide and vessels up to 1000 tons could be loaded for some years until the berth began to silt up. Although the harbour never showed more than £50 or £60 of profit on the annual trade, it allowed the colliery business to prosper. Loading coal at Bridgeness saved nearly a shilling a ton over the cost of rail and shipping at Bo’ness.

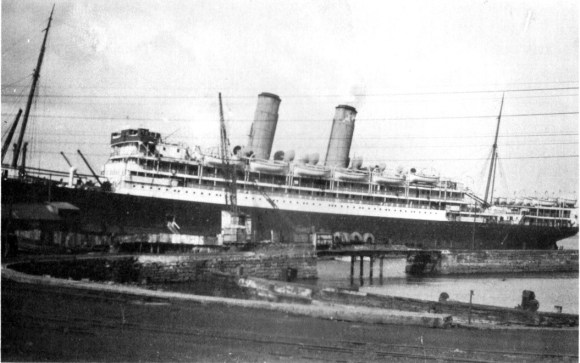

In 1905 W R Fairlie, a Glasgow iron merchant of good standing, took a lease of the inlet between the harbour and the breakwater where he could break up the iron ships then being scrapped. The business did well and was taken over by P & W McLellan Ltd and became the Forth Shipbreaking Company Ltd. Considerable damage was done to that breakwater in March 1906 by heavy seas, but it was soon repaired. A greater threat to the future of Bridgeness Harbour emerged in 1911 when the North British Railway Company wanted to reclaim yet more land to the north-east of its Dock for a new pit. It was pointed out that the effect of reclaiming this land would be to divert the flow of the current northwards, forming a projecting groyne, which would have the result of closing up the mouth of the harbour at Bridgeness. The land already taken in by the NBR was presenting problems as it was. The cost of dredging at Bridgeness for the 17 years to 1905 averaged £24 13s. From 1905 to 1910 the average annual cost was £44. Since 1910 Cadell’s dredger had not proved powerful enough for the purpose, and he was endeavouring to get Mr Wilson, who dredged Bo’ness Dock, to attend to it. Wilson, however, was too much occupied at Bo’ness Harbour. The result was that the bottom of the harbour at Bridgeness became so silted up as to become dangerous in places.

This came to a head on 8 June 1911 when a vessel of 599 tons register berthed in Bridgeness Harbour and slipped off a mud bank, breaking her hawser and windlass and sustaining considerable damage. Cadell had to pay the owners £110 in damages. He attributed the accident entirely to the excessive siltation caused by the NBR’s reclamation over the years immediately previous. The proposed expansion by the North British Railway Company was thus endangering the livelihoods of a large number of people who worked at Bridgeness Harbour as well as 120 men in the adjacent shipbreaking yard.

The outbreak of the First World War took many by surprise, including the captain of the German ship the Mienje. He owned the vessel which was at Bridgeness loading coal at the time. In the first week of August 1914 the Customs officials at Bo’ness, accompanied by police officers, proceeded to Bridgeness and seized the German schooner. The German flag and ship’s papers were taken possession of and the British flag hoisted. The captain and his small crew of three were held overnight as prisoners in Bo’ness before being taken to Edinburgh.

In the middle of November 1914 the Admiralty closed the upper Forth to mercantile shipping. As most of the coal from the Grange estate was shipped to Denmark from Bo’ness and Bridgeness it had to be sent for shipment to Leith, Granton or Glasgow, which involved rail dues of 2s 1d a ton or more – a serious trading disadvantage. By the end of 1914 the colliery was running without profit. It was not allowed to do dredging at Bridgeness during the war and consequently the harbour all but silted up during this period. It was estimated that the loss sustained by the temporary closure of the harbour was £2,000. After the war the cost of the necessary dredging operations was prohibitive. It was therefore with considerable irritation that Cadell appealed against an increase of the rateable valuation from £70 to £200! He won the appeal. The harbour was left to deteriorate.

The land reclamation to the east of Bridgeness harbour left a small bay open to the sea and in 1919 the Forth Shipbreaking Company Ltd leased it with the first ship, the Marco Polo, a Norwegian sailing vessel salved in the Orkneys, arriving in August, followed by HMS Mercury. In 1923 the Carriden Shipbreaking Company was set up to run the new yard. The presence of the breaking yards encouraged more people to acquire small boats – they often bought the lifeboats from ships being dismantled. In 1932 the Bridgeness Yachting Club was revived, having been disbanded in 1913. H M Cadell presented it with his old rowing boat, the Laverock, which had been laid up in the Old Smithy for 40 years. He also gave the club a strip of land to the west of McLellan’s Yard upon which they then built a clubhouse.

During the Second World War, the shipbreaking yards were busy salvaging material from ships that were too badly damaged to be repaired. McLellan’s extended into the old harbour at Bridgeness. An unlikely adventure arose from the Victoria Sawmill of Thomson and Balfour when it hired land adjacent to the Carriden Yard to fabricate motor launches and motor torpedo boats for the Navy (see Bailey 2013). A concrete slip was built for launching these craft and a motor and cradle could be used for hauling them out for repairs. The end of the war brought with it a fleet of obsolete ships and the dismantling continued.

.

After over two centuries of coal mining the Cadell family sold the Bridgeness Colliery to Carron Company in 1934. The coal was taken away by rail for use at Carron. However, the Company hit geological problems and decided to close the colliery in June 1939. H M Cadell stepped in and kept it running throughout the Second World War until August 1946, when it closed for ever. The reason for having a harbour at Bridgeness no longer existed. The Victoria Sawmill, which lay immediately to the south-east of the harbour, used Bo’ness Harbour where the timber handling facilities were better.

The harbour was filled in over a period of 30-40 years. In 2007 part of the flood prevention barrier was built over it, leaving just the end of the pier exposed on the coast. The pier’s large sandstone blocks capped with granite blocks still make an impressive appearance. The western breakwater can also be traced, but it is a mixture of concrete, iron boilers, and stone.

Sites and Monuments Record

| Bridgeness Harbour | SMR 1503 | NT 0146 8170 |

| Carriden Shipbreaking Yard | SMR 2065 | NT 0201 8146 |

| Carriden Boatyard and Slipway | SMR 1502 | NT 0215 8148 |

| Victoria Sawmill | SMR 1660 | NT 0150 8160 |

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 2013 | The Forth Front; Falkirk District’s Maritime Contribution to World War II. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 2021 | The Antonine Wall in Falkirk District. |

| Cadell Papers | National Library of Scotland. | |

| Ellis, G | 1791 | ‘Parish of Carriden,’ Old Statistical Account; County of Linlithgow. |

G.B. Bailey, 2024

Appendix

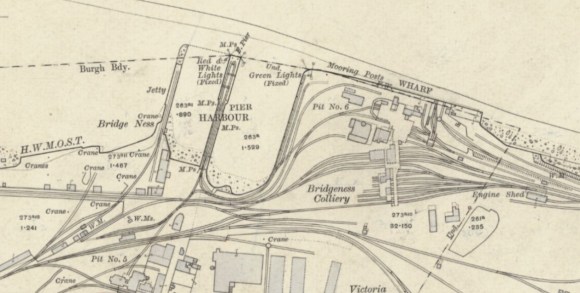

Ordnance Survey maps (National Library of Scotland) showing the progress of land reclamation to either side of Bridgeness Harbour.