The shape of the coastline of the Falkirk district has been radically altered over the years by taking in parts of the extensive mudflats that were only covered by shallow water at high tides. The earliest reclamations of land from the Forth Estuary would have been accidental. Two processes immediately come to mind – saltpanning and shipping. The former produced waste material – briguetage (the ceramic vessels used) and a small amount of ash. Around 1550 the fuel source changed from wood and peat to coal and the amount of ash increased significantly. It was dumped in the immediate vicinity of the pans, as was seen in the archaeological excavations at St Monans in Fife. In the Falkirk area the salt industry moved from the upper end of the Forth to the area around Bo’ness where the coal was more readily available and dumps of ash can be found at Kinneil, Corbiehall, Bo’ness and Bonhard. The impact from shipping was varied. Even the construction of the simplest of piers to facilitate the landing of ships will alter the flow of the water in its immediate vicinity and result in still waters dropping their silt, creating new banks of mud. As ships grew in size the depositing of ballast also became significant enough to become a hazard to vessels entering the harbours of the Forth and in the 17th century several Acts of the Scottish Parliament attempted to regulate the activity. Larger and larger ships had to be accommodated, and in the late 19th and early 20th centuries huge wet docks were carved out of the mudflats and the adjacent land thus formed was used to service them.

The Forth provides an active high-energy environment of great variety. By and large the south coast is much more prone to the deposition of water-borne silt than is the north bank. The material is largely derived from the turbulence of the incoming tide disturbing material. During stormy seasons this rolling action is greater and the particle burden is correspondingly greater. However, there are also areas of erosion focused on promontories such as at South Alloa, Higgin’s Neuk, Carras Pans at Carriden, and Blackness. In those areas substantial stone defensive dykes were constructed in the 18th and early 19th centuries. These often replaced earlier earthen banks and simply by extending them laterally more land could be taken in.

The vast areas of mudflats on the south side of the Forth were an obvious target for reclamation work. They were left high and dry at each tide’s ebb and were only covered by shallow water in between. The terms “sleeches” or “sloblands” are used for these places. Just how early sea dykes were built in order to reclaim new land rather than protect that already existing is not known. Smout and Stewart hint at the possibility of a start in the medieval period, but this is unlikely. A tack of 1636 at Ferriton near Clackmannan may be indicative of practice elsewhere at that date. There the tenant was required to see to “Repayrying and re-edifieing of the hale sea dykes demolished be Invadations of Walter and sail menteyne the same in as gud estait as they have bene thay yens bypast” (Harrison 1996, 72). However, it is one of the earliest known examples. In the Falkirk area most of the earliest references to sea dykes are actually along the River Carron. Although it is tidal up to Camelon, these should be seen as river defences.

With the settled agrarian conditions that arose after the union of the crowns, through the late seventeenth century and the Act of Union in 1707, landowners paid more attention to improving their estates and increasing the yield therefrom. Trade contacts with the Dutch were plentiful, particularly at the ports of Bo’ness and Airth, and perhaps ideas of land reclamation came from there. In 1710 Sir Robert Sibbald mentions such contact:

“There is but a small distance betwixt the Mouths of the Water of Carron and Avon: and the Firth here is very Shallow upon this South side for a long way, because of the vast quantity of Earth and Rubbish brought down there by Speats: the Shallowes have the name of the Ladies Scap, where there is great variety of Shells of diverse sorts found, both Marines and Fluviatiles: The Dutch did offer some time ago to make all that Scape, good arable ground and Meadow, and to make Harbours and Towns there in convenient places, upon certain conditions which were not accepted: The Dutch have made many such Improvements in their own Country with their dykes: It is thought this might make the narrow part of the Firth deeper and the Navigation to the upper parts more commodious, if this design were prosecuted.”

Not that such reclamation was unique to the Dutch.

In any case the process must have already begun at Airth for by 1726 (Shaw 1810) the old shore line had been advanced with the reclamation of over 100 acres. This date is supported by archaeological evidence from within Airth burgh (see below). A tack for the unusually long period of 42 years at Airth dated to 1696 required the tenant to maintain the sea walls. The length of the lease suggests that the land had been newly reclaimed and therefore required improving.

Only at Kinneil do we have a hint of earlier sea dykes. These appear to date to around 1474 (Salmon 1913, 26) and were still being actively defended in 1697 when a tack required the tenant “to keep the tide thereof.” These lands, however, seem to have been sea greens or salt marsh rather than mudflats before their reclamation. Cattle could be grazed on such sea greens which only flooded at spring tides. Once enclosed and the sea excluded, they could be converted into fertile cultivable land. Then new salt marsh would form on the seaward side of the embankments – a process that can be seen in action today at Newmills near Higgin’s Neuck and at Powfoulis.

The late 18th and early 19th century witnessed a great deal of active reclamation by the major riparian landowners to provide additional agricultural land. The Old Statistical Account for Airth of 1793 notes that -“Within these 25 years, 300 acres have been gained from the river Forth, and made good arable ground. It is defended from the river by a strong dike of sods“. Likewise, in Bothkennar, the next parish downstream, land was being obtained in this way:

“Within these few years, a considerable extent of ground has been gained in this parish and neighbourhood from the Frith, which, though defended at great expence, will soon become a valuable acquisition to its possessors”

(Dickson 1793).

The pace of land reclamation in Stirlingshire at the turn of the eighteenth century was considerable and attention was drawn to it in the “General view of the Agriculture of Stirlingshire” published in 1812 (Graham, P. 1812 p274):

| In 1788, by Lord Dundas | 90 acres |

| In 1806, by the same | 24 |

| In 1809, employed in reclaiming | 60 |

| Within these 40 years, by the Earl of Dunmore | 120 |

| About to be reclaimed, upon the same property | 50 |

| Reclaimed by Mr Graham of Airth | 70 |

| Reclaimed by Mr Ogilvie of Gairdoch | 70 |

| Reclaimed by Mr Gilmour | 30 acres |

| 514 |

The same source also gives particulars of the embankments used:

“With regard to the manner in which these embankments are constructed, the Reporter finds that a year or more before the bank is built, facines of brushwood are fixed down in the clay, by strong palisades, in the line in which the embankment is to be conducted; and over which it is afterwards actually built. By this lie of facines, the mud and floating vegetables, which would otherwise be washed away, are arrested, and a considerable addition made to the soil. The embankment is made of mud or earth, faced, on the side that presents itself to the sea, with large stones, which are procured from the quarry of Longannat, on the opposite side of the firth. The strongest of these embankments are 40 feet wide at the bottom, and 12 feet high, having a slope of two feet to every foot in height. In some situations, a bank of 7 or 8 feet in height is found to be sufficient. A dyke of this kind will defend from the sea for ages; and is kept in repair at an expence so trifling that tenants have no objection to take the burden upon themselves.”

This process of inducing the dropping and accumulation of the silt is known as warping. Late 19th century reclamation was aimed mainly at industry as it produced a higher rent. For this purpose, the land had not merely to be defended from the sea but also raised above the level of the high tides. Fortunately for them, by this time there was a large quantity of cheap suitable material available to act as landfill – the industrial waste produced by coal mines, foundries and oil production. In turn, the reclamation sites provided a cheap means of disposing of such waste, and when fully reclaimed the land could be used for more rubbish-producing plant such as coal mines exploiting the undersea reserves – a virtuous circle, of a type.

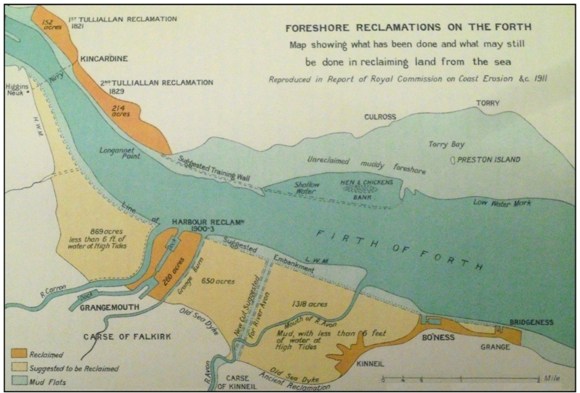

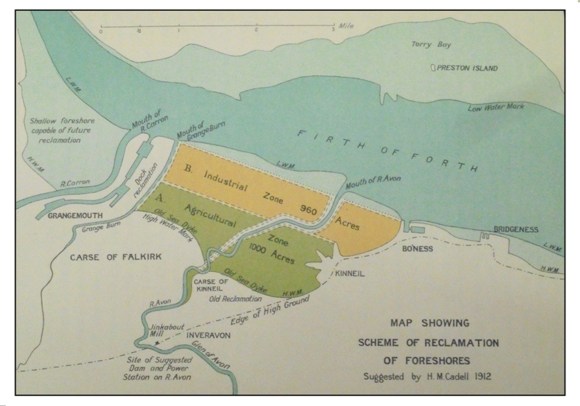

It is likely that the Dutch scheme mentioned by Sibbald was rejected due to the rival claims of the multitudinous riparian landowners, large and small, all of whom possessed various rights to the foreshore. Certainly, this was the case with later large-scale proposals. In 1875 Thomas Livingstone Learmonth of Parkhill, who then had a large fortune at his command, prepared a scheme to reclaim 3,600 acres of that foreshore from Grangemouth to Bo’ness, the cost of which was estimated at £275,000. Learmonth’s Bill was withdrawn from Parliament owing to the opposition of Lord Dunmore, Lord Zetland and others in the House of Lords. So he went to Denmark, where the terms offered were more favourable, and spent his fortune there reclaiming about 11,000 acres (Cadell 1912). H.M. Cadell, in his book on the Forth went over the plans and estimates and thought that, with some important modification as to the method of working, the greater part of the land, some 2,837 acres, might be reclaimed for less than half Learmonth’s estimate. He calculated that £100,000 would be sufficient giving a cost of £38 per acre. The estimate included £60,000 for the necessary embankments.

Then in 1880 there was a scheme of reclamation put forward by Meik & Son coupled with a proposal to form a Conservancy. Still later there were suggestions submitted by Thomas Meik, civil engineer, Edinburgh, and Henry M Cadell of Grange, to the Royal Commission on Coast Erosion, appointed by the Government in 1910-11, for the reclamation of 2,000 acres by the formulation of a straight embankment more or less along the line of low water mark between Bo’ness and Grangemouth.

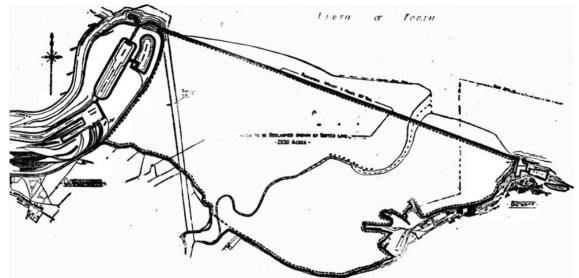

The cost of Cadell’s scheme made it economically unviable. However, the depression of the 1920s brought the proposal back to the attention of the public as a possible means of state-funded intervention to provide employment. The well-known Bo’ness architect, Matt Steele, was an advocate and produced a much-discussed plan showing a straight embankment, three miles and 167 yards long, from the entrance lock at Grangemouth Docks to the end of the West Pier of Bo’ness Harbour. This embankment would have doubled as a wharf for shipping and hence the project was sometimes linked with a proposal for a Mid-Scotland Ship Canal to replace the Forth and Clyde Canal. Steele’s plan also shows the diversion of the River Avon to the mouth of the Grangemouth Docks. The cost was put at a mere £3 million. Such grandiose schemes never stood a chance.

It remained the case that carting vast quantities of material, constructing sea walls and then maintaining them were troublesome, expensive and unusual. In any case, attitudes to such reclamation had changed. Writing in 1797 the minister at Bo’ness had lamented the collapse of the Dutch scheme stating that “the project failed, and a large extent of ground remains useless, shewing its face every 24 hours, to reproach the fastidiousness and indolence of mankind.” This was still the way of thinking in 1875 when the Stirling Observer commented on Learmonth’s proposal: “the mud flats remain a disgrace to the district, whose inhabitants, in other respects, are so enterprising” (Stirling Observer 25 November 1875, 2), and was that possessed by H.M Cadell. It was only after the Second World War that people began to appreciate the natural history of these areas.

Within the last few decades another factor has crept in and that is rising sea levels resulting from global warming. The mudflats on the Forth have always provided a safety valve for the surplus water to occupy. With more water this is even more vital and has led to the deliberate breaching of the old sea walls in the area of Powfoulis and Skinflats in order to provide greater capacity and at the same time it has created saltwater lagoons which provide a wonderful habitat for wildlife, particularly birds. This is known as the Skinflats Managed Realignment project. Further down the coast at Bothkennar Pools land subsidence caused by the earlier mining has led to the formation of freshwater lagoons on the formerly reclaimed foreshore.

The River Carron to the River Avon

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 1990 | ‘Excavations at the Burgh of Airth,’ Forth Naturalist & Historian, 14. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 2023 (a) | ‘The River Carron & the Grangemouth Lighthouse,’ FLHS website. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 2023 (b) | ’Grangemouth 1768-1872,’ Calatria 37, 17-103. |

| Cadell, H.M. | 1912 | The Story of the Forth. |

| Cadell, H.M. | 1929 | ‘Land Claim in the Forth Valley: I Reclamation Before 1840,’ Scottish Geographical Magazine, 45, 7-22. |

| Dickson, D. | 1793 | Parish of Bothkennar in The Statistical Account of Scotland 1791-99. |

| Graham, J. | 1812 | General view of the Agriculture of Stirlingshire. |

| Harrison, J. | 1996 | ‘Between the Carron and Avon,’ Forth Naturalist and Historian, 20, 71-91. |

| Porteous, R. | 1994 | Grangemouth’s Modern History, 2nd ed. |

| Reid, J. | 1999 | ‘The Lands and Baronies of the Parish of Airth.’ Calatria 13, 47-80. |

| Reid, J. | 2009 | The Place Names of Falkirk and East Stirlingshire. |

| Salmon, T.J. | 1913 | Borrowstounness and District. |

| Shaw | 1810 | Plan of Airth Pow. Scottish Record Office |

| Sibbald, R. | 1710 | History and Description of Linlithgowshire. |

| Smout, T.C. & Stewart, M. | 2012 | The Firth of Forth: An Environmental History. |

| Summers, J. | 2009 | ‘Grangemouth Docks: Rails to the River,’ Steam Days 244, 22-733. |

| Ure, R. | 1793 | Parish of Airth in The Statistical Account of Scotland 1791-1799. |

| Wilson, T. | 2023 | ‘Wilson’s Log,’ transcribed and edited by Bailey, G.B. for FLHS website. |