In the 16th century the supply of water at Bo’ness was obtained from wells, many fed from springs, and the quantity was not problematic because the population could be counted in the hundreds and the wells were numerous. With the great increase in trade that occurred over the following centuries the population grew considerably and water shortages occurred. The matter was made much worse by the coal mining in the hill to the south which disrupted the flow to many of the springs. As this activity increased, more and more of the springs were affected and by the middle of the 18th century the problem of water shortages was becoming acute.

The wells of this late period were artificial in that the water was piped in from elsewhere for distribution at the well-heads. The Town Well, also known as St John’s Well, was created in 1669. The well-head sat in the old Market Place on South Street at the junction with Schoolyard Brae and was placed over a stone tank or reservoir. The water had to be pumped out using a hand-operated mechanism. The original source of the water may have been at the Braehead where a large fountain head or storage tank is shown on the 1855 Ordnance Survey map on the south-east corner of the junction of what are now Braehead Road and Cadzow Lane.

An Act of 1769 gave the Harbour Trustees of Bo’ness power to contract for springs and build reservoirs, but there were no funds. The only sums that the Trustees could raise were by voluntary subscription using an assessment and from the liberality of the Dukes of Hamilton. Petitions and complaints were frequently lodged, and in June 1778, it is minuted that “Almost the whole town is in great distress for want of fresh water, which has of late become exceedingly scarce” (Salmon 1913, 255). It was therefore resolved to get estimates from properly qualified surveyors to bring water to the town through lead, earthen, or wooden pipes. Although not clear, this was probably an attempt to augment the supply to the Town Well which as well as serving the town centre was also used to supply ships in the harbour. A few years were spent in getting the estimates and in September, 1781 it was decided to tap a site at the Western Engine to the south of the town near Graham’s Dyke (the Antonine Wall) and to lead it down to the meeting-house by means of an open ditch. In the end wooden pipes were used and the work was contracted out to Charles Sinclair for £187.

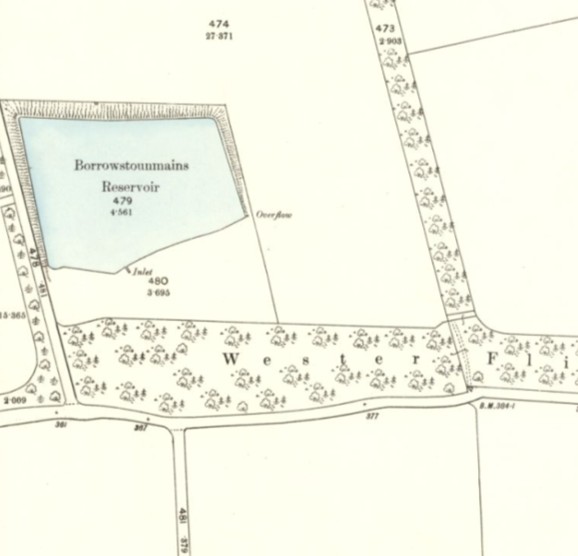

Bo’ness expanded northwards using land reclaimed from the Forth and so it was not possible to sink wells in the northern quarter of the town as salt water would inevitably seep in. In 1818 it was decided to establish another pipe-fed supplementary well in the new market square on the south side of North Street. It was necessary to augment the original source and so additional hard water was obtained from the vicinity of the hamlet of Borrowstoun, 1.2km to the south, where a small reservoir was constructed. Here there was an ancient well known as St John’s Well.

Trials were made using wooden pipes but the pressure of the water due to the difference in height was too much and so they had to resort to cast iron supplied by the Shotts Iron Company on the lower ground.

The new well in North Street was welcomed but the pipes to it bypassed those living up the hill to the south of South Street. In 1825 a memorial was submitted to the Harbour Trustees representing the grievances of some of the population.

The main problem was the want of a sufficient supply of soft water, and the deficiency of the number of wells. It was stated that the diameter of the water pipes was completely inadequate to the consumption of 630 families. Their request therefore was that the trustees should devote the assessment made on the town solely to the supplying of all parts of the town with water, that they should cause pipes of a sufficient size to be laid from St. John’s Well to the reservoir, that they should leave a branch pipe at the corner of the school area for the accommodation of the scholars and of nearly thirty families residing in that quarter (a great proportion of whom were old people, and very unable to carry water up the hill), and that they would cause two additional wells to be erected for the benefit of the east and west ends of the town, and adopt such regulations as would prevent any of the water from being carried out of the parish. They concluded by stating that if the Trustees refused their requests, they would feel it a duty incumbent on them to resist payment of the assessment, and to seek redress in a higher quarter (Salmon 1913, 262). In fact, the assessment was not there for the sole provision of water and over the previous two year £433 had been spent upon it which was more than the sum raised in a single year.

The water must have been pumped out of the pit by its operator in order that he could work the coal. New distribution pipes were laid in the main street and additional wells added.

In 1868 the Trustees for the Town and Harbour of Bo’ness used the Public Health (Scotland) Act, 1867, to form a Special Water Supply District from Thirlstane on the east, to the western boundary of the grass glebe of the Minister of the Parish of Borrowstounness on the west; and from Graham’s Dyke on the South, to the sea at low water of Spring tides on the north. This gave them powers to obtain land and borrow money. That year the Temple Pit closed and a new supply had to be found. It turned up at a neighbouring pit to the east – the Causey Pit at Northbank. Mr Barrowman, the town’s engineer, arranged for a mine to connect the sources underground and in June 1869 it was completed by Alexander Lumsden for £66 12s 3d. Mr Begg, the pit owner, agreed to get the water pumped on Sundays in order to supply the town, and also during the Bo’ness fair holidays. At this time it was raised from the Causey by a gin driven by two horses and allowed to gravitate into the reservoir. In August 1869 it was reported that the pump, which

“had been going for two days this week, as it now stood showed 22 feet of water” (Falkirk Herald 7 August 1869, 3).

It was agreed to get a practical person to inspect the workings, and ascertain where the best point would be from which to obtain a continual supply. It was also agreed to advertise for contracts to undertake the erection of the necessary machinery for pumping the supply and Grangepans was added to the grid. However, it was discovered that the water in the Causey Pit was too low to be of use and Mr Barrowman provided what water he could spare from the Mingle Pit. During the summer drought in 1870 the town had to rely upon the Bo’ness Distillery of Vannan & Begg for water. The time that the public were allowed to draw water from the system was limited. For the time being Bo’ness had to rely upon water pumped out of the mines and this was not sustainable.

Augmentation of the water from No. 25 Pit near Bonhard was considered to be too expensive and so the Trustees looked at a possible source at Avonbank, but William Forbes would not agree to its use. John Paul, the town’s master of works, and Mr Barrowman, then investigated the Cauldwell Spring and the Langland Springs near Inveravon. They were considered to have insufficient water. Provost Dawson offered water from his Bonnytoun estate, but again it was too small. And so in 1875 they returned to No. 25 Pit for a temporary supply. Polmont Hill and Myrehead were looked at.

In August 1876 the master of works summed up the situation:

“Nearly the whole of the country for the distance of seven miles southward of Bo’ness is highly cultivated and thickly populated, and the various systems flowing through it have been more or less utilised for mills and manufactories, and their waters so polluted as to render them very unsuitable for domestic use. I have therefore directed my visitations chiefly to those portions of the district where the springs have not yet been appropriated, and where tolerably clear surface water can be obtained…

Polmont Hill Scheme – the burn to the westward of Polmont Hill rises in Gardrum Moss about four miles further west, and flows into the Avon a little below Polmont Neuk. This burn, from which an ample supply could be obtained for the lowest part of the town becomes so contaminated in its course as to be quite unfit for domestic use when it reaches Gilston Farm, and apparently, on this account, the Grangemouth authorities, who are taking a supply a little below this point, have sunk a series of bores near to the portion from which they are to draw a limited supply, instead of from the burn, which they are taking every precaution to exclude from their supply pipes. Immediately above the spot of their operations, and upon the property of the Duke of Hamilton, there are a few unappropriated springs rising on the east side of the burn. These springs drain a basin of about 200 acres, and if they were all collected at the lowest point, they would yield a minimum supply of about 45,000 gallons per day. There would, however, be great difficulty in collecting and separating the particular springs from the surface water, which, unless carefully filtered, would not be of good quality.

The available spring water supply from this district cannot therefore be safely assumed at more than 25,000 gallons per day. It is not improbable, however, that it might be increased by putting down two or three bores. In addition to the spring water, about 150,000 gallons of surface water per day might be obtained by the construction of two reservoirs. The height at which the water could be drawn off would be about 100 feet above high water. It would therefore be available only for that portion of the town lying below the 80 feet contour.

I have intimated the cost in two ways – 1st, for a supply of 25,000 gallons of spring water, the supply pipe to extend to the harbour, if taken by tunnel direct, the cost would be £4,500; if taken by the deviation round the hill, £2,500; 2d, for 100,000 gallons direct by tunnel, including reservoirs, filters, & c. £7,000; do, by detour, £5,200.

Myrehead Scheme – this is a large flat district, having a drainage area of 500 acres, and the minimum of water in the burn at the lowest point would seldom be less than 100,000 gallons per day, but there are no well-defined springs. It would therefore be necessary in dealing with the district to construct reservoirs in it, from which would be excluded all flood water. There are no good natural sites for such reservoirs, and they would require to be mostly excavated, which would materially increase the cost. The level at which the water can be drawn off would be about 110 feet” (Falkirk Herald 19 August 1876, 4).

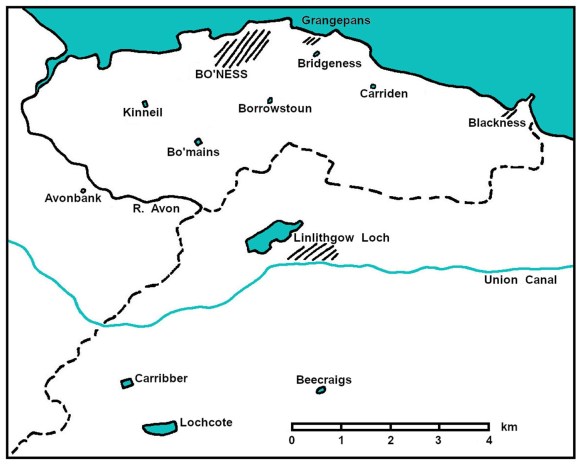

The matter could not be laid to rest and so the Trustees employed Stewart and Menzies, engineers, Edinburgh, to report upon various sources which had been suggested. After surveying the country within ten miles of the town they reported in favour of a supply being drawn from springs issuing from the limestone rocks at Bowden Hill, near Easter Carribber, about two miles south-west of Linlithgow. In September 1876 the Trustees unanimously approved of and adopted their recommendation. The Scheme included the formation of a collecting reservoir at East Carribber, upon the property of Mr Blair of Avontoun, capable of containing about 15 million gallons of water. An iron pipe, 7 inches in diameter, would take the water by way of Linlithgow Bridge, Little Mill, and Bo’mains, to a screening tank (Borrowsoun 2)), situated on the high ground at Borrowstoun village, and distant about five miles from Carribber and one mile from Bo’ness. Filters were not considered necessary at this stage. The scheme was devised for an ultimate delivery of 350,000 gallons per day. The pipeline had to cross the Avon valley and ascend the hill at Flints, considerably reducing the water pressure to the Borrowstoun reservoir. At the same time, a complete system of new service pipes was laid throughout the town and suburbs and also to the docks.

Owing to the great scarcity of water in Bo’ness. the pipeline was laid and water delivered directly from one of the springs called the Pappa Hole in September 1878 before the reservoir at Carribber was constructed. McFarlane & Co, Glasgow, provided the cast iron pipes. In July 1878 the contract for that reservoir was awarded to Masterton for about £1,400 and completed on 5 June 1879 with a capacity of sixteen million gallons at a cost of £1,175

A series of summer droughts persuaded the Bo’ness Commissioners of the need for a large reservoir above the town to even out the seasonal supplies of water and so they entered into negotiations with a view to obtaining ground at Bo’mains for the construction of a service reservoir. The work was under way by John Gallacher, the contractor, when the drought of 1883 struck and in June it was announced by tuck of drum that the water supply would be cut off from 4pm until 8am each day. Arrangements were made to repair the equipment at the Causey Pit and recommence pumping there to tide the town over. Bo’mains reservoir was completed on 10 June 1884 at a cost of £2,000, having an area of six acres and a capacity of 16,112,719 gallons.

Shortly after the opening of this reservoir it was discovered that the 7-inch pipe between Carribber and Bo’mains was not discharging a sufficient amount of water and the reservoir was taking too long to fill. It was initially thought that there was a blockage and then that the calibre of the pipe was too small. Eventually it was realised that the severe gradients were largely responsible. Tunnelling through Flint Hill was considered but in 1889 the pipe track was diverted round the hip of the hill through the lands of Muirhouse, and thence in a northerly direction to Bo’mains reservoir at an estimated cost of £174 12s 9d. Despite the problems, the town had weathered the summer shortage at this time without the need for restrictions.

A good deal of excitement had been caused the year before by the appearance in a local paper of an article which attributed the prevalence of sore throats and a number of cases of diphtheria to the quality of the water. The medical officer and the master of works had the water examined under the microscope and showed that the water was not to blame – the newspaper publicly withdrew its allegation.

There had been some discolouration of the water due to the cleaning of the Pappa Hole and Carribber reservoir. The Pappa Hole was shortly afterwards deepened and protected and the water led by piping into Carribber Reservoir. Three years later, on the advice of Leslie & Reid, C.E., Edinburgh, the reservoirs at Carribber were deepened, in order to impound all the water available from the catchment area. The capacity was thereby increased from 16,000,000 to 25,441,419 gallons, thus giving a combined storage in all the reservoirs of 42,000,000 gallons, or 56 times more than that contained in the Borrowstoun Reservoir 42 years previous. A new 10-inch pipe was also laid along the same route between Carribber and Bo’mains.

The area to be supplied, however, had also increased, with Grangepans and the parish of Carriden being fed from the burgh through a meter at the rate of 6d per 1000 gallons.

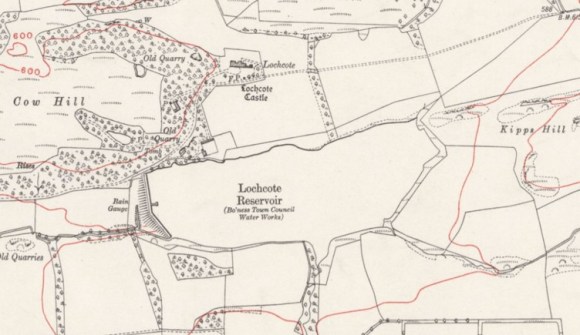

The majority of the inhabitants within the burgh at this time did not have water fed into their houses but obtained their supply from pillar wells, 40 or 50 of which at one time existed. The source depended almost entirely upon the winter rains and so had to be augmented in some summers by water from the Schoolyard Pit. Occasionally the supply to the public works had to be cut off. Clearly a new source of water was needed. Riccarton Burn, Lily Loch, and Lochcote, were all visited and the latter was chosen. Its advantages were that it had :

- a heavy rainfall;

- a large catchment area of grass land free from moss;

- a natural basin of large holding capacity, which only required an embankment across the narrow neck at one end; and

- it was only two miles from the existing main pipes at Carribber.

A Provisional Order was applied for during the Session of 1897, and after a stiff fight the Commissioners made good their case, and became the possessors of 50 acres of land, with water rights and wayleaves. To give immediate relief to the inhabitants, No. 1 contract, which included the laying of two miles of 12in pipes from Brunton Burn to Carribber, was begun and completed in the short period of two months by the contractors. The construction of the embankment was begun in the spring of 1898. It was considered that a year would see this section of the work completed, but owing to unforeseen circumstances, such as the deepening of the puddle trench, the scarcity of men, and the unfavourable weather conditions, it was not completed until the autumn of 1900. The valves were closed on the 5 June 1900, and in five and a half months, 30 December, owing to the exceptionally heavy rainfall, the reservoir was full and overflowing. The total capacity of the reservoir was 200,500,000 gallons, or nearly five times more than all the others combined, with a catchment area of 600 acres. The cost, inclusive of the purchase of the land, was £30,000. The construction of the reservoir alone cost £14,000.

With the introduction of Lochcote, the difficulty of storage capacity was successfully overcome. There still remained, however, the question of distribution, as it was very soon demonstrated that the mains were totally inadequate to deliver in sufficient quantity the water now available to all parties, when the docks and public works were in full swing. While considering this scheme, the question of filtration was also discussed, and after a free exchange of opinions, it was carried by a majority of one that efficient means of filtration ought to be introduced. A scheme was prepared and successfully carried through by Mr Lawrie, the Commissioner’s engineer, which comprised the breaking of the bank at Bo’mains, the cutting out of two 6-in pipes, these being substituted by a 15-in pipe through the bank to the valve house, and thence led across the field to the corner at Hamilton Gate on Kinneil Old Avenue, at which point the filters were situated. Six batteries of Bell’s mechanical filters were installed at a cost of £2,500, capable of filtering 1¼ million gallons in 24 hours. The lifetime of the filters was put at 30 years. The remainder of the scheme included the laying of an 8-in pipe from the filter house to convey a supply of unfiltered water solely for work purposes, and the laying of several service pipes within the burgh, opportunity being taken to connect the various branches, so as to avoid dead ends and affect a free circulation of the water throughout the entire system, the whole work being executed at a cost of £5,000. Adequate means were also taken as opportunity presented itself for dealing with outbreaks of fire by the introduction of fire hydrants. The aggregate length of iron pipes, ranging from 15-in to 2-in, was 22 miles.

The consumption of mains water by businesses in the Burgh in 1900 was 51,460,000 gallons and by 1912 this had risen to 114,793,000. Some of the public works had their own reservoirs. The distillery, for example had taken on the reservoir at Kinneil, and the Bridgeness Coal Company had reservoirs in Kinningars Park.

APPENDIX

1. Kinneil Reservoir

The reservoir at the west end of Kinneil estate was designed by James M Gale, C.E. of Glasgow in 1860 and tenders were submitted for the work in March 1861. It covered six acres and had earth embankments along the east and north-east sides. It seems to have been built to provide water for the estate and its farms and houses. Mr Learmonth of Grangepans was given permission to use a water waggon to convey some of the water to his home village where it was a scarce commodity. In 1876, however, the full and exclusive use of the water from these ponds was leased to Bo’ness Distillery for all the necessary uses and purposes of the distillery. It tapped the Cauldwell Springs near Upper Kinneil. In 1880 the distillery, requiring larger amounts of soft water, led additional water from the Union Canal into the Cauldwell pipe, a distance of around 3km. This was augmented in 1892 by a separate pipe from the canal all the way to the reservoir. As a result of the latter the Duke of Hamilton took James Calder & Co, distillers, to court, as they had no permission to introduce the additional water or to cross his lands with the pipelines.

In November 1900 nearly 200,000 gallons of water escaped from the Kinneil Reservoir and flooded the Snab locality. The damage was estimated at roughly £400 (Linlithgow gazette 23 November 1900, 4).

After Bo’ness Town Council had acquired the Kinneil estate it was suggested, in September 1932, that it should also acquire the water rights of the reservoir from the Distillers’ Company Ltd., to form a bathing pond, sections of which could be allocated for pleasure boating and the sailing of model boats.

2. East Pond, Kinneil

The East Pond at the Meadows was built sometime between 1820 and 1855. It was formed by erecting an earth bank across the point where the valley of the Deil’s Burn widens out at the top of the escarpment, and lining the inner slope with clay and stone. It had a stone-lined culvert with a sluice. It is quite large at 0.97 acres but appears to have been solely for the use of the estate.

3. Bridgeness Reservoirs

Grangepans and Carriden parish were supplied from wells until around 1890 when a pipe was led into the area by the Bo’ness Commissioners and surplus water was supplied at 6d per 1000 gallons. The Provost of Denny referred to the generosity of the Bo’ness Burgh in doing so, but HM Cadell of Grange was not so sure:

“it is of wretched quality. It has been repeatedly so yellow and muddy as to be scarcely fit for domestic use, and has often, as it has just now, a disgusting odour, which does not disappear on boiling, and renders it both unwholesome and quite unpalatable, while on several occasions it has been reported to contain sundry ugly inhabitants of a very suspicious character. Notwithstanding repeated complaints to the Commissioners, no steps have apparently been taken by them to filter the water or otherwise improve its quality. We do not mind paying a fair price for a pure article, but we decidedly object to have to pay for the other undesirable ingredients, all of which are accurately measured out to us by meter. We can buy animal food at other shops, and mud is cheap at this part of the Forth, and when we can get as much as we want gratis, it is scarcely generous to charge 6d per 1000 gallons for it” (Linlithgow Gazette 21 October 1893, 6).

Such surplus water (and mud) was not always available and 1893 witnessed a great drought which resulted in the supply to Grangepans being cut off for many weeks causing much stress to the community. Henry Cadell related what happened:

“I was asked to get a supply out of the old Miller Pit that had been derelict for half a century, but which the old people said used to have a good stream running through the bottom towards Kinneil. We put up an engine and lifted the water by a bucket. At first it seemed abundant and good in quality, but after the wastes had been emptied the average daily growth was found to be not more than 10,0000 to 12,000 gallons, which was quite inadequate to meet local requirements. I laid a 6″ S.M. clay pipe from the Miller Pit to the reservoirs above Bridgeness and in the upper of these I made a set of filter beds to help to purify the water. Also I laid a 6″ field drain from the Miller’s Pit right across the south fields of the Drum to the SE corner of Grange Estate at Carriden Road, to intercept all the available water above that line and draw it into the reservoirs. This drain was 1,000 yards long and took a good while to lay. But these operations, although meant at first to help the public supply, were also intended subsequently to improve the supply to the reservoirs that were used for the boilers at the colliery, and since then this source of water has proved very useful there.

These works, however, were not completed till the end of the year, by which time the drought had broken and a normal rainfall had replenished the empty reservoirs. The colliery was the only party that finally benefited.

The Bridgeness Coal Coy also supplied, for a time, the water from No.9 Pit, which however was much contaminated and had to be treated with lime shells and then filtered before it could be made reasonably wholesome for domestic use. It served for a time to tide over the famine until the Miller Pit supply could be tested.

However, it was evident that any water I could squeeze out of Grange was quite inadequate both in point of quantity and quality, and we were dependent on getting a regular supply from Bo’ness. The Bo’ness Burgh Commissioners under the able chairmanship of Mr GC Stewart met and resolved to petition the sheriff to extend the burgh boundaries so as to include Grangepans and the populous part of Kinneil. This proposal met with great opposition in Grangepans and I did my best to oppose it, as the people were quite well pleased to be under the County Council and did not want to bear the higher taxation the burgh would involve. We considered that the extra benefits would cost more than they were worth. The further development of the question did not take place till next year.

1894 saw Grangepans absorbed in the burgh of Bo’ness, of which it became the East Ward – much against the wishes of the inhabitants. Sir George Trevelyan, the radical Secretary for Scotland, granted the request of the Bo’ness Commissioners after an enquiry on 26 December and henceforth Grangepans ceased to be a separate village. No doubt there was higher taxation, but personally I was saved a great deal of trouble in no longer having to look after sanitary affairs and provide water at a pinch. The extension of building and sanitation was a thing for a burgh surveyor to attend to and we were henceforth shareholders in the general water supply and no longer dependent on getting any surplus that Bo’ness might be able to spare.” (Cadell nd).

During the 1893 crisis Cadell modified the existing reservoir at Bridgeness, which must have been built to supply the colliery, as he noted in a letter to the Linlithgow Gazette of 23 October:

“As it is much easier for a private firm like the Bridgeness Coal Company, than for a public body like the County Council to take in hand and carry out such work expeditiously at first. I am likewise busy constructing a settling pond and extensive filter beds in connection with the old reservoir above Bridgeness, by means of which the greater part of the district may in future be supplied with clear and wholesome water, and when these works are completed arrangements may be made with the Linlithgow District Committee to take them over, or otherwise make use of them at a cost which shall, I hope, prove a benefit to all the ratepayers in the district. If the County Council does not see fit to do this, the works can be utilised by me for other purposes...”

The great drought of 1911 cut off the water supply for the engines at the colliery and so a pump was fitted on the old Doocot Pit and raised a lot of water. It was put into the Bridgeness reservoir but it was very hard and left crusty deposits in the boilers and as soon as rain fell it was stopped.

The reservoir was utilised as an Emergency Water Supply tank during the Second World War and was slighted soon afterwards. It survived as an earthwork into the 1950s and subsequently levelled as part of the public park.

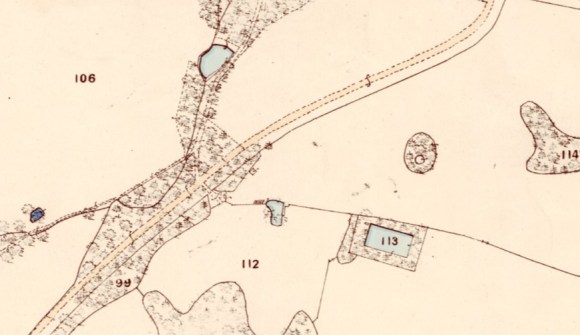

4: Carriden Reservoirs

A rectangular reservoir appears on the 1855 Ordnance Survey map 400yds to the south of Carriden House. The reservoir, much silted up, is still present and fully lined with stone. Nothing has come to light regarding its origin.

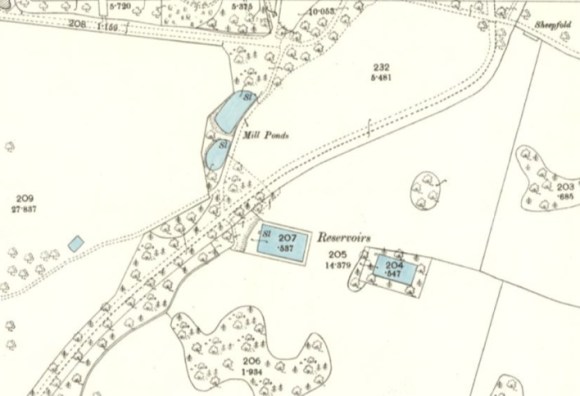

The old reservoir had a small pond almost immediately to its west and this was redeveloped some time before 1895 into another large rectangular tank. Major work to the Carriden supply was being carried out in 1878 and the reservoir may have been part of that. After the extension of the Burgh of Bo’ness in 1894 it came into its ownership.

In 1911 a 10-inch pipe was laid from the filter house at Bo’mains reservoir to the reservoir at Carriden. The contractors were John Hardie & Son of Bo’ness for laying the pipes, and Robert McLaren & Co of Glasgow for the pipes.

Sadly, the reservoir became famous for drowning. In April 1930 a 45-year old man from Muirhouses died there; and in July 1938 a 19-year old, also from Muirhouses. In each case it was described as a service reservoir.