Bo’ness Road

The Scottish Oils refinery at Grangemouth began production in 1923 and required its own electricity generating station for power and lighting. It had steam turbines and by 1948 “modern oil-fired water-tube boilers, charged with water which has been chemically treated and de-aerated” to provide the steam (Veitch 1948, 40).

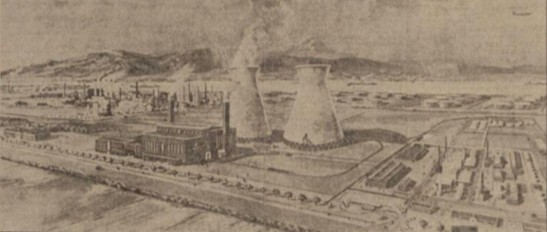

As a result of unrest in the Middle East and the low value of the American dollar, it was agreed in 1948 that a refinery complex destined for that part of the world should instead be attached to the existing small refinery at Grangemouth. The project was vast, covering an area of 550 acres to the east of the previous complex and north of the road to Bo’ness. Its projected cost was £6.5 million and included new distillation, thermal reforming and catalytic cracking plants for the production of high-grade motor spirits. The plans envisaged the production of some 215,000 tons of motor spirit and 370,000 tons of heavy fuel oils annually, together with considerable amounts of kerosene, gas oil and tractor fuel. The dock installation handling the importation of Middle East crude oils had to be upgraded to cater for the extra traffic. The frontage along the Bo’ness Road was extensive and Scottish Oils Ltd produced an artist’s impression of how it was going to look. Behind an impressive 80-feet high power station verging the road, would stand two 200ft tall cooling towers, with low office and laboratory buildings nearby. The cooling towers were larger than those at the Bonnybridge Power Station and would dominate the Forth.

The area was rich farmland and was not particularly suitable for building heavy plant. That December bores were sunk to a depth of 100ft revealing that the subsoil was soft and that innovative engineering solutions would have to be found. They were. It was decided to float the bigger buildings on buoyant concrete rafts. This method of foundation had not before been used on anything approaching this scale in Britain. Four of these great rafts, the smallest of which was 75ft by 54ft by 14ft deep, were constructed on the surface in the form of giant honeycombs. Then mechanical diggers scooped out the soil below them and they were slowly lowered into the ground to a depth of 19 feet where they floated on the soft mud of the subsoil after the bottom of each cell had been sealed watertight. When the four rafts were in position they were welded together into one huge raft. The last of the four rafts for the power station was sunk into position at the end of November 1949. To ensure that the ground below them was restored to its pristine strength, the contractors had resort to an electrical device perfected by the Nazis during the building of the great U-boat pens around the Atlantic coast. The German scientist, Loe Casagrande, who pioneered the device, known as electro-osmosis, came to Grangemouth to supervise the work. A charge of electricity was passed into the ground through one terminal, causing the water in the ground to gather and flow towards the other terminal. The electrical charge also reorganised the particles of the soil to the strength they had before being broken up by digging. In operation the apparatus was visually unimpressive, with three mobile generating sets on one corner of the site and a 2-inch diameter cast-iron pipe rising from the ground on the opposite corner. From the pipe a trickle of water issued which was then pumped away by more conventional types of pumps. The method was effective, but expensive. Altogether, it was estimated that these four rafts alone cost £100,000 to construct and sink.

The method of constructing the foundations for the two cooling towers was also new to the country.

These concrete rafts took the form of huge inverted plates, distributing the weight of the towers so that it compared closely with the weight of the 25,000 tons of earth which has been excavated to sink them. The job also took months to complete but in September 1949, well ahead of schedule, three thousand tons of water, nearly a million gallons, were poured into the reservoir base of the first tower to test for stability. The foundations barely moved with the additional weight. By the end of the month the scaffolding for the tower and a central structure had been run up over 70 feet. J.L, Kier & Co Ltd, London, were the contractors for the superstructure.

A reporter from the Falkirk Herald was given access to the site and was fascinated and disturbed by the nature of the work:

“This disrespect for the law of gravity appears, too, at the top of the tower where workmen nonchalantly wheel their barrows of cement along a narrow platform, with no guard rail to save them from a drop of over a hundred feet. Joiners and setters, some with safety belts discarded, cling to the outer edge as they prepare the moulds for the rising wall. Though most of the men are strangers to this type of work, they already seem at much at home as the sparrows who have begun to build their nests in the holes left for the lightning conductors. Inside the tower, some 20ft below, are the highest-paid men of the job, the “spider men.” Their work is to dismantle beneath their feet the web of “climbing scaffold,” and pass the pipes up over their heads to their mates who re-erect them above. This scaffold is a unique feature of the work. It is unsupported from the ground and held only by clamps fixed to the inwardly sloping walls of the inside of the tower. It supersedes the older method of filling the entire interior of the tower with a “bird-cage” of scaffolding.” (Falkirk Herald 26 November 1949, 5).

Around a quarter of a million feet of tubing was used for the scaffolding, specifically placed so that no unnecessary weight was added.

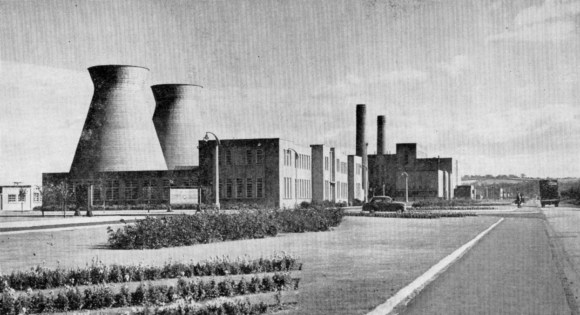

The topping off ceremony for the first cooling tower took place in the last days of January 1950. The time taken to construct the 200ft tower from ground level, including all of the time lost due to bad weather and holidays, was 19 weeks – which was a world record! The average height constructed each week was just under 12ft. And all this was done with local labour which had never before worked much above ground-level – the only exception being the scaffolders who were Welsh. Just on the 90ft mark most of the local joiners left as they felt they had gone high enough, but some of them later drifted back and remained on the job until completion. Altogether, 6,000 tons of concrete were used and the total weight of the tower was about 7,000 tons. Over 100 miles of steel reinforcement strengthened the structure.

The second of the twin giant cooling towers for the new power station was completed on 9 June, slashing the previous record and setting a new one of 13 weeks and three days. To mark the occasion a pennant was broken from the top of the tower, and later the workers repaired to the Douglas Hotel, Bo’ness, to celebrate. They reckoned that if the concrete could have been got to set faster the tower could have been completed even sooner!

Work on the superstructure of the power station had begun in November 1949 and was complete enough by the beginning of February 1950 to allow the installation of the machinery. The twin 120ft tall chimneys were finished at the end of August. The following month the Herald reporter was back:

“Inside it looked for all the world like the engine-room of some big ship. The great boilers seemed to rise almost to the roof 80 feet above, with workers at every level of the steel gangways, riveting, welding and hammering. On a higher level the big turbo-alternators were being fitted onto massive concrete beds, and down corridors leading from the main building were the control rooms, their entire length filled with a mysterious array of equipment” (Falkirk Herald 16 September 1950, 5).

He added that you might describe the power hall as a sort of cathedral.

On Thursday 14 December 1950, with snow lying all around, the great 20,000KW power station stirred into life and thin wisps of smoke trailed from the chimneys. Each cooling tower now held some 6,000 tons of water in its reservoir foundation which was designed to be cooled to 40 degrees at the rate of 1,500.000 gallons per hour. The hot water came from the power station and was returned there when cooled.

Like many a power station, that at the Refinery had been designed so that its capacity could be readily increased and this was done in 1954/55 at an estimated cost of £25,000. In 1966 the go ahead was given to extensions costing about £3.6 million to meet the estimated 1968 steam and power requirements to the refinery, British Hydrocarbon Chemicals, and associated companies in the petro-chemical complex at Grangemouth. The scheme has been approved by the Secretary of State for Scotland, and included three major developments.

Biggest of these was a contract worth about £2 million, placed with Simon Carves, Manchester, for the installation of two 300,000-pounds-per-hour steam boilers, two 17½MW back-pressure turbo-alternators and associated station electrical switch-gear, increasing the capacity of the refinery power station from 25 to 60MW and from 1.2 million to 1.8 million pounds of steam per hour. Because of the comparatively high steam pressures, a high quality water was essential, and to meet this requirement a water clarification and demineralisation unit was supplied by Permutit as a separate contract. The third part of the development was the establishment of two new 33KW switching stations adjacent to the power station and on a B.H.C. site. Cabling linked these with the South of Scotland Electricity Board grid system. The entire project was completed for autumn 1968.

In February 1975 one workman died and another was injured in a fall inside one of the chimneys at the BP power station. The men were working high up inside the chimney doing maintenance when they fell, landing on scaffolding about 120 feet above the ground level.

In April 2001 BP commissioned Fortum, an international power generation and distribution company based in Finland, initially in conjunction with Mitsubishi of Japan, to build and operate the replacement gas-fired combined heat and power station on the site. Fortum set up a UK-based subsidiary called “Grangemouth CHP Ltd” (CHP – combine heat and power). The new station comprised a 130MW Siemens V94.2 gas turbine. It also supplied steam to the Grangemouth Refinery and the nearby Kinneil Oil Stabilisation and Gas Separation plant. In 2014 Fortum agreed to sell the power plant to the new owners of the refinery, INEOS, for £54 million. The power generation capacity was put at 145MW with heat generation of 257MW.

In 2019 Fluor was awarded the contract for a New Energy Plant of 35MW by Ineos which was to take into account new developments in carbon capture and the use of hydrogen from the refinery. After construction work had proceeded on site, with piling operations completed, the plans were shelved in June 2022 and shortly afterwards it was announced that the refinery too would close. The last day of crude oil refining occurred on 29 April 2025.