As Falkirk entered the 1860s it had just finalised an agreement with John Wilson of South Bantaskine to direct water from his underground coal workings into the earlier abandoned wastes which the town had used as a giant underground reservoir or basin for decades. In March 1861 the Provost was able to state that

“the water had now been brought into the cistern, and the wells were supplied with an abundant quantity” (Falkirk Herald 28 March 1861, 3).

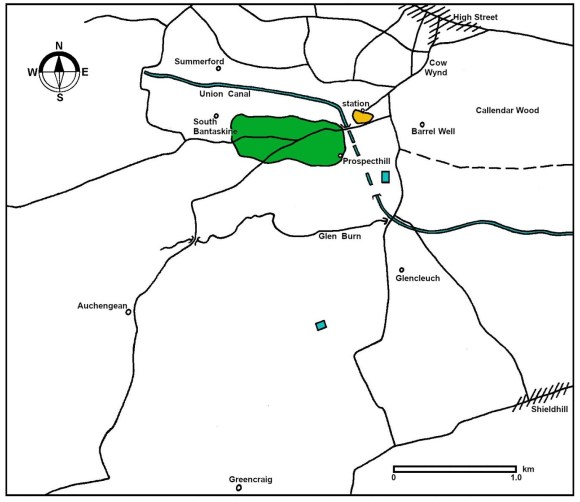

The basin from which the Town was formerly, but scantily, supplied with water, was in the ancient coal waste which was about 2½ acres in extent, and lay between the Union Canal and the town. This subterranean basin was bounded on the south, west, and north by solid coal; while on the east a ridge of solid rock separated it from the old waste in Callendar Wood. In the early 19th century it had been augmented, on a small scale, by water from old workings on a higher level south of the Canal. The point at which the water was taken from the basin and fed into pipes to the town was known as the Fountainhead and lay at the top of Drossie Road near the later railway station. The pipes led to a series of public taps placed in stone settings at the sides of the streets, known as wells.

There was another division of old workings running from Greenhorn’s Well under the old quarries in the direction of South Bantaskine in which there was also a considerable quantity of water. It was separated from the town’s basin by a stone ridge. This water had several outlets, one of which was under the canal bridge, and a second at the foot of the hill near the cottages at South Gartcows. The periphery of this coal field was still worked by John Wilson and over the years about 80 acres of additional coal wastes were created, extending from South Bantaskine eastwards and south to Prospecthill. A large basin in these workings dipped to the south-east from Standalane farmhouse towards the direction of Prospecthill, and from this point Wilson needed to run the water off in order to continue his operations.

Hearing complaints every summer about the scarcity of water in Falkirk, Wilson had suggested to a number of the leading gentlemen connected with the town in the early 1850s that, by an outlay of several hundred pounds, the whole of the water from South Bantaskine to Prospecthill could easily be taken to the town. To remove the water himself in order to continue working the coal to the south would require an expensive siphon and so he offered to pay a fourth of the amount necessary for a mine to lead it into the town’s basin.

This plan was not agreed to and consequently he installed the siphon and proceeded to work the coal. Some years afterwards he was approached by the Feuars seeking water, and agreed to abandon the working of the coal which then remained, but only if William Forbes, the landlord, consented; and having laid out hundreds of pounds on roads, siphons, and other operations necessary to work the entire coal, he required a sum in compensation. The Feuars corresponded with the Stentmasters on the subject, and together they agreed to pay £120. In consequence Wilson waited upon Mr Forbes, who generously agreed to leave this portion of coal unwrought for the public good. The terms were then agreed to, and Wilson ceased working in that basin.

The connecting mine was then dug. It was several hundred yards long and was driven through the ridge from the old basin under the canal tunnel house to the other basin near Prospecthill, and took advantage of an existing air mine. However, before the final arrangement was signed, the chairman of the Feuars died and a lull took place. Wilson therefore left his siphons, rails, and other material in place until the Provost and Magistrates of the town’s new administration arranged to carry out the former agreement. Meanwhile, Wilson allowed the water to rise till it flowed through this new mine nearly a quarter of a mile to the old basin, and the inhabitants enjoyed the flow of water in the interim (at least as much as their old pipes could run). With the agreement finally signed, in June 1861, he had to reduce the water in the new basin in order to remove his siphon, rails, sleepers, & c. During this period the new supply of water was muddied and many vocal complaints were made that the water coming into the town was dirty. James Aitken & Co was one of the main users and beer making was affected. The disturbance was of short duration and afterwards the water supply was greatly enhanced in quantity, and included water from the Britannia Pit. The lead water pipes from the Fountainhead to Falkirk were replaced by much larger ones of cast iron. This material was now readily available for such use and was a game changer in improving the distribution network. In October 1861 the Provost stated that

“so abundant was the supply that they were compelled to run off a great portion of it to waste” (Falkirk Herald 10 October 1861, 3).

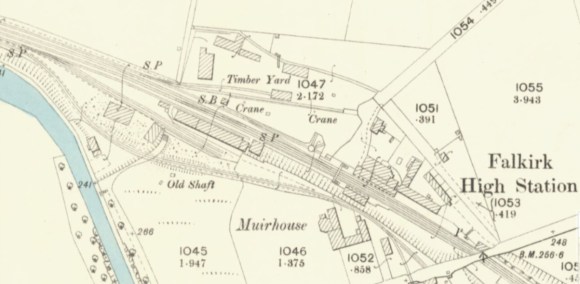

Things looked well set for the foreseeable future. Then, at the end of 1862, the North British Railway Company decided to extend its sleeper creosoting works at the High Station. Despite having contaminated the town’s water supply just a few years earlier when it originally established the works, creosote soon saturated the ground, both inside and outside the new building, till the supply of water was rendered quite unfit for cooking or drinking. The Police Commissioners threatened the Railway Company with legal action and quickly secured the removal of the works. The North British Railway Company paid for the contaminated water to be pumped out of the old basin but it was some time before the creosote stopped seeping through the ground (see Coast – Pitwood Imports: wooden railway sleepers ). Some of the affected works that used the town water sought financial compensation from the railway company. James Aitken & Co resorted to carting water from Marion’s Well. In the meantime it was agreed that the North British Railway would pay for the digging of a new mine so that the water from the new basin could bypass the polluted old basin and be fed directly into the town’s pipes. Despite attempting to get out of this agreement, the company did pay £200 and provided old rails and sleepers to Mr Borland who was driving the mine. William Black, the town’s consulting engineer, oversaw the project. It was some time before the water in the old basin could be utilised.

All along the town’s representatives had dealt civilly with those from the North British Railway. This was just as well, for in 1867 they approached the Company for a supply of soft water for washing purposes from the Union Canal. The water had been analysed and found to contain neither lime nor iron, and to be relatively free of organic matter. In fact, a pipe had already been laid for a supply of water from the canal in cases of fire, during the pleasure of the Company.

Now it offered to supply water to Falkirk on the ordinary terms – 4d per 1000 gallons consumed. The town’s officials had hoped for a better offer, but had to accept. To keep the consumption down, locks were placed on the wells so that no person could get access to soft water unless furnished with a key. The new supply was turned on at the beginning of the new year and in the course of the first two weeks some 11,500 gallons were used. The water gave great satisfaction; and some individuals considered that it was softer even than that from Marion’s Well.

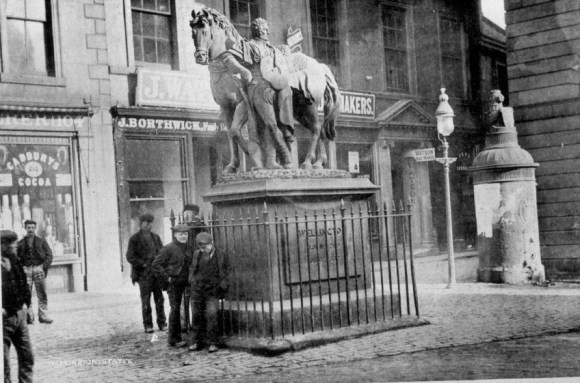

Although the supply of water was thus increased it was failing to keep up with demand. In 1859 the distribution of the water by the Stentmasters had been limited to the old burgh of regality, beyond which it had no remit to operate. Even within the burgh the system was restricted to the central part of the High Street and the immediately adjacent closes. It was only extended to the west and east gates of the town in 1863, and it was 1877 before the pipes were led into the Howgate. New uses were being made of the water. In 1863 two fire-hydrants were put in, one at either end of the High Street, at which the fire engine’s water barrel could be filled. This was seen as “an experiment made as to the capabilities of the water supply, for the extinction of fires.” The demand from businesses increased exponentially and this provided a revenue stream with which to make the improvements.

Despite the 1859 Police Act, which enlarged the burgh, it was some time before attention turned to providing water to Grahamston and Bainsford. In 1870 it was decided to supply Grahamston directly from the Union Canal and the North British Railway Company agreed to allow the pipes to bypass the cistern in the town centre. For this it was to be paid £5 a year, or more if the four wells in Grahamston were increased in number. Comments were made that the water turned clothes yellow when used for washing, but there was little alternative. The number of wells was soon increased to ten but it was not long before the local children were accused of damaging them and wasting water.

.

A small embankment was inserted into the basin to increase the depth of water. It cost a mere £50. Even with this enhanced storage capacity the supply was often insufficient in the summer months. 1875 was particularly dry, and many houses on the High Street were without water for weeks on end. Even the Cross Well had no water. There was talk of banning the use of public water for gardens and hothouses (an early form of the hose-pipe ban). The following year restrictions were introduced early to stave off such depravations:

“WATER SUPPLY. NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN, that it has come to the knowledge of the Commissioners of Police that a considerable WASTE of the TOWN’S WATER arises from parties using it for Washing Carriages, as well as by Builders, Plasterers, and other Workmen in their Trades; and in order to put a stop to such misuse of the Water, and its appropriation to other than Domestic and Ordinary Purposes, Intimation is now made, that, Parties hereafter Offending will be Prosecuted. Farther, that to accommodate Innkeepers, Stablers, Contractors, and others who require Water for other than domestic purposes, directions will be given by Mr MITCHELL, Inspector, at his Office in the Council Chambers, for their obtaining a supply of Soft Water, which must be taken in Barrels on Carts to be supplied by the Users.

By Order, ROB. HENDERSON,

Clerk to the Commissioners of Police…” (Falkirk Herald 29 June 1876, 1)

It is therefore surprising to hear yet another optimistic provost stating that:

“he might now congratulate the Commissioners, and the people of the town generally, on the successful conclusion to which the operations of the Water Committee had been brought. He believed they were now in possession of an overflowing supply of good water, and that the question was happily closed for a good many years to come. Not the least of the good features which the question offered was that of economy. The whole expenditure would probably not exceed £414, and of that the Railway Company were good for £114. The water presently stood at 9½ ft, but he had been advised to let it stand at 9 ft. There was even a waste of 60 gallons per minute…” (Falkirk Herald 9 August 1877, 4).

The Police Commissioners, however, knew that they had to augment the water supply. They sought and obtained permission from William Forbes to supplement the existing system of tunnels by joining them with the subterranean network to the east under Callendar estate. It was introduced in 1879, and the supply was still found to be inadequate for the increasing requirements of the people. The scheme was supposed to have included a supply from Greencraig Pit, but that needed the cutting through of the intervening whinstone dyke which was going to be expensive. This was problematic and so alternatives were sought.

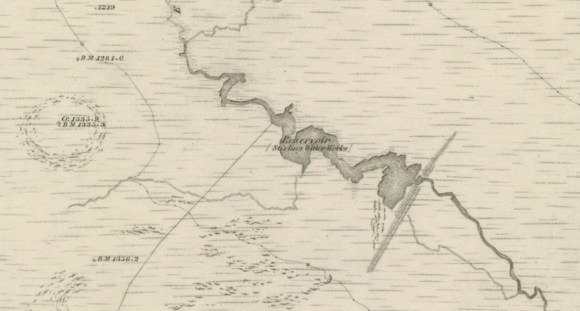

Many schemes were put forward and rejected – so many that the representatives of the Burgh of Stirling made fun of their Falkirk colleagues and the public became disillusioned. Notable amongst these schemes was one by James Leslie Chief Executive of Edinburgh who had experience with the water supplies to Edinburgh and Dundee. He had put forward a Loch Coulter scheme but it had not been taken up. Traditionalists still believed that the high ground to the south of the town was the obvious place to seek the water. Bailie Blackadder submitted his Auchengean Scheme in opposition to that of Greencraig and it had enough merit to cause a rethink. By contrast, Provost Cockburn, Alexander Brown, William Black Chief Executive. visited the old reservoir on the Earl’s Burn which had been built for the mill-owners of Denny (Bailey FLHS website). A month or so later the Commissioners resolved to employ William R. Copland of Glasgow, who specialised in drainage and water supply, to make a report on probable sources. He reported on three schemes and their probable cost. As a result the Auchengean scheme was discarded on account of its cost. Copland indicated a preference for the scheme at the Denny Hills and proposed two alternatives – one from the Earl’s Burn alone, or one from Loch Coulter supplemented by the Earl’s Burn. Most councillors were in favour of the Denny Hills but, given the high costs, they opened the question to discussion by the public.

Meanwhile, Bailie Blackadder and Ralph Stark of Summerford investigated the ground at Camelon between the railway and Dorrator and discovered a number of strong springs and proposed that water be pumped and sent into the town as a supplementary supply. The Camelon Scheme was cheaper than the work at Greencraig, especially as in the summer of 1883 the Bailie offered to provide a pump at his own expense. He ran an engineering business specialising in such machinery. So this scheme was included in the voting paper as one of the three before the Commissioners. Blackadder and Stark canvassed for their scheme. Accompanied by a woman carrying two sample pitcherfuls of water, they appeared at ward meetings and handed the water around the audience. When the plebiscite papers were counted the ratepayers had voted in favour of the Camelon Scheme. As a consequence six councillors resigned – Provost Cockburn, Bailie Christie, Councillors Baird, Gartshore, Hutchison and Anderson. New elections were held and afterwards Provost Hodge had to look at the problem anew, with priority given to the Camelon Scheme which the public had backed. The water there was tested and the cost determined. It was considered unsuitable on both accounts. Of the two springs under consideration north-west of Camelon, one was found to be subject to contamination from the cemetery. So a scheme at Lochgreen, proposed by Councillor Griffiths, was examined along with a new version of the Greencraig one. Instead of introducing the Greencraig Pit water, recommended by William Black, it was proposed to store the existing water supply in a reservoir to be constructed at Parkfoot. Lochgreen was visited, and the requirements carefully examined, but in June 1884 it got its quietus by the casting vote of the Provost, and by the unanimous decision of the Council the reservoir scheme at Parkfoot was shelved.

A drought later that year meant that the question was becoming urgent. The schemes were re-opened and a new one at Bell’s Meadow introduced. By means of pumping it was estimated that from the various springs in the meadow a supply of something like 118,000 gallons per day could be obtained, and this, in conjunction with the existing supply, was considered sufficient. However, fears were entertained that on account of its situation the water might be subject to contamination and so that scheme too was abandoned. At the August 1884 Council meeting the proposed cutting of the whinstone dyke was again debated. The meeting was stormy and at the end Councillor Simpson proposed a motion in favour of the Earl’s Burn Scheme. In September this was estimated to cost £40,000, and it was adopted.

Immediate steps were taken to promote a bill in Parliament in the ensuing session and it was duly lodged. Ward meetings were meagrely attended and all, except one, were in favour. However, opposition slowly grew, including by some who favoured a different source in the Denny Hills. In response it was pointed out that the Council wished to avoid opposition from Sir James Gibson Maitland and the mill-owners on the Bannock. So vocal did the opposition become that the Commissioners were forced to withdraw the bill in January 1885.

Mr Robertson C.E., Glasgow, was asked for yet another report on a scheme suggested by the protestors. He reported on Glencleugh and Auchengean. He estimated that both sources would yield a supply of a quarter of a million gallons daily, which would just about answer existing wants. The cost of works was estimated at £5,875, not including the prices of land or legal expenses which would bring it close to £10,000, It was promoted by Mr Griffiths, but soon had to be quietly expanded. Before the public it transpired that it had been modified and now resembled in form that of Copland’s Auchengean scheme which was estimated at £10.500, increasing to £19,000 with legal and land expenses. A second public meeting rejected the scheme outright, but this was disregarded by the Council. They did, however, ask Robertson to cost the changes and the new estimate, exclusive of legal and land expenses, came in at £12,500. It was put to public plebiscite and again rejected. At the next Council elections those candidates in favour of a Loch Coulter Scheme were selected, including Messrs Baird, Cockburn, Simpson and Young. They quickly adopted Copland’s combined Loch Coulter and Earl’s Burn scheme and it was put before Parliament in 1886. At last it looked as if a solution had been found. However, Sir James Gibson Maitland and others with vested interests opposed it and the House of Lords Committee refused to pass it (Hill 1992).

It had been an expensive series of failures and although the town had to proceed with caution there was a pressing need for the additional water supply. A temporary expedient was required to tide it over until a comprehensive scheme was adopted and carried out. Arrangements were made with Ralph Stark of Summerford for the pumping of water from Summerford Pit. At little cost this scheme was carried out, the water pumped from the pit being conveyed to the Old Fountain, and mixed with the existing supply. It had been estimated that the Pit would yield around 70,000 gallons a day and might come down as low as 50,000. For 61 days from 23 April 1887, 4,230,000 gallons were pumped, an average of 67,300 gallons per day. The daily average from 22 June to 29 June was 58,500 gallons, and from 30 June to 4 July, 54,000. It was thus clearly shown that continuous pumping reduced the supply. The cost per annum of pumping 70,000 per day was £290. The plant cost £3,560. With it the total supply of the town was 235,000 gallons per day, made up of 100,000 gallons from the “mine mouth,” 70,000 from Drossie Road, and about 65,000 from Summerford Pit.

In 1887 Provost Weir favoured the use of artesian wells such as those which were already in use by some of the local industries in the Falkirk area. On examination it was found that they were not producing sufficient water and would be too expensive to run.

At the same time the full Council had commissioned James M Gale CE, Glasgow, to make an exhaustive examination of the whole district. He was well respected and his connection with the Corporation of Glasgow precluded his employment in the implementation of his recommendations and meant that he was considered to be unbiased. His report of September 1886 gave an estimate of the cost and the capacity of three separate schemes – namely, Skipperton Burn, Buckie Burn and Faughlin Burn.

The first of these was a revamped version of the Lochgreen Scheme. For the Skipperton scheme two reservoirs were proposed – one below Lochgreen House, capable of containing 87,031,250 gallons, and one above Burnhouse, capable of containing 42,368,750 gallons. The first reservoir was estimated to cost £2,550 and the second £2,370, which with filters and tanks for 510,000 gallons a day, a 12-inch main pipe, price of land, & c, made a total cost of £24,955. It would not yield the quantity of water required and what there was, was of objectionable quality.

The Buckie Burn scheme provided for three reservoirs – one on the Wee Buckie Burn, with a catch-water conduit. It would have had a capacity of 9,540,000 cubic feet – 59,625,000 gallons. The middle reservoir on Buckie Burn, was for 7,863,000 cubic feet, or 49,143,750 gallons. The lower reservoir at the same place, 3,756,000 cubic feet, or 23,475,000 gallons. The first reservoir was estimated to cost £4,350; the catch-water conduit £770; the middle reservoir £3,474; and the lower reservoir, £5,606. The other expenses made up a total for this scheme of £48,625.

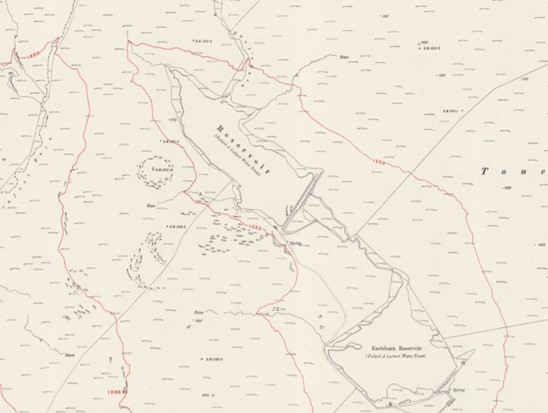

The Faughlin Burn scheme was also designed to have three reservoirs. There would be one at Faughlin Burn, having a capacity of 4,688,000 cubic feet, equal to 29,300,000 gallons. A reservoir at Little Denny Burn would have a capacity of 15,664,000 cubic feet, and would give 97,900,000 gallons. There would also be a compensation reservoir on Garts Burn, which would have a capacity of 24,000,000 cubic feet, and give 150,000,000 gallons. This water was needed to replace that which would otherwise have gone into the River Carron and served the mills downstream – it was known as compensation water. The Faughlin Burn reservoir would cost £3,760; Little Denny Burn Reservoir, £7,330; and the compensation reservoir, £1,610. The other expenses incidental to the formation of these brought up the total of this scheme to £50,800.

Of the three schemes, Mr Gale recommended the latter, as best suited to the town and district, having the best quality water and meeting demand for years to come. The Falkirk Herald was scathing

“If there is a great scarcity of water in Falkirk, that is not the case with water schemes. Each succeeding year seems to bring along with it a fresh supply of schemes for discussion, but, alas! Hitherto they have had no other result than to increase the debt of the town by payments to engineers, lawyers, and other professional men. The last Scheme cost between four and five thousand pounds, which were just as completely thrown away as if they had been cast into Loch Coulter” (Falkirk Herald 25 September 1886, 2).

The temporary respite provided by the Summerford Pit, it continued, had merely allowed the Commissioners to continue

“the vacillating and procrastinating policy of our municipal rulers in all their dealings with the water supply of the town”.

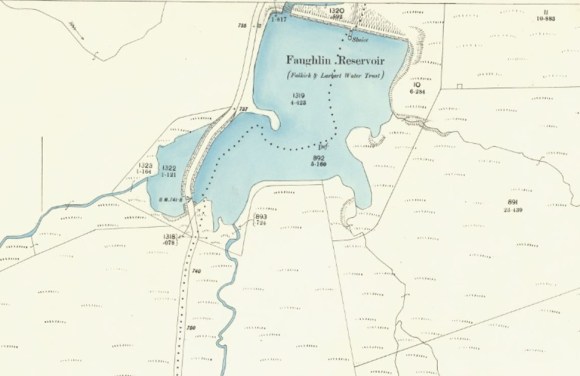

The Provost too was not a keen supporter. Provost Weir believed that they could get by simply by reducing wastage at the wells. In the summer of 1887 he visited the Faughlin Burn and gave it as his opinion that it would not provide sufficient water and wanted to revive the Loch Coulter Scheme. He was a lone voice. Other members of the Falkirk Council visited the sites of the proposed reservoirs at Little Denny and Faughlin that July and liked what they saw. The ground was of little agricultural value meaning that there would be no pollution from that source and that the land would be cheap. Councillor Cockburn pushed the Faughlin Burn Scheme. Learning from past experience it was decided to widen its scope by including the districts of Denny, Dunipace, Larbert and Stenhousemuir. That September meetings were held with representatives of those areas. The Denny Police Commissioners employed Kyle, Dennison, & Frew, civil engineers, to examine the situation and came up with its own scheme to obtain water from the Garvald Burn. Despite the set-back, Falkirk Council resolved to proceed with the Faughlin Burn Scheme and to appoint William Copland as engineer and Mr Beveridge as Parliamentary agent. The Local Authority of the Parish of Larbert decided to join them and agreed to form the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trust. The Bill was lodged at Westminster on 17 December 1887. The 45 page Bill was entitled “A bill to incorporate a public trust for better supplying with water the burgh of Falkirk, and districts and places adjacent; and to make and maintain new and additional waterworks; and for other purposes” or the “Falkirk and District Water Act, 1888.” The Trustees were to number seventeen, with five from the Police Commissioners of Falkirk; five Elective Trustees, to be elected by persons beyond the burgh of Falkirk (four of which were to be from Larbert). The Bill provided powers to make new waterworks, including reservoirs, filters, water tanks, and embankments, with roads of access and lines of pipes to reservoirs, and so on with powers to borrow up to £80,000. The area covered was to comprise and include the burgh of Falkirk, the burgh of Denny and Dunipace, and the burgh of Grangemouth, and the villages of Larbert, Stenhousemuir, Bonnybridge, Camelon, Carron, Carronshore, and Laurieston, etc.

Despite having been involved in its formulation, Carron Co opposed the Water Bill in a transparent attempt to wreak economic concessions. The House of Lords seems to have recognised flaws in the company’s argument and dismissed its objections. The paper manufacturers at Denny were also against it as they claimed that the compensation water was insufficient and not of the same quality as the soft water they had been using. Adjustments were made and on 24 July 1888 Royal Assent was granted.

In December adverts were posted asking for tenders for the works, which were to be divided into three sections. Contractors were invited to tender for the whole, or for one or two sections only.

Section No 1 comprised the construction of a Compensation reservoir on Earl’s Burn, a Supply reservoir on Faughlin Burn, a conduit of cast-iron pipes 4¾ miles in length from Faughlin Burn to Little Denny Reservoir, and other contingent works.

Section No. 2 comprised the construction of a Storage reservoir, filters and clear water tanks at Little Denny; a conduit of cast-iron pipes connecting reservoir with filters, and other contingent works.

Section No. 3 comprised the construction of a Main Conduit of cast-iron pipes 6 miles in length, from the site of the filters at Little Denny to Falkirk; a Main Conduit, 4 miles in length, from Dunipace Bridge to Carronshore, the various branch pipes required within the Burgh of Falkirk and the Larbert Water District, and other contingent works.

Last minute adjustments were made. More land was acquired from James Graham, agent for Forbes of Callendar, allowing the embankment and water level at the Little Denny Reservoir to be raised to the full extent of the limits of deviation allowed in the Act – 5ft, thus increasing the storage capacity from 98 to 135 million gallons. The capacity of the Faughlin Burn Reservoir was to be 32 million gallons in place of 29. The Earl’s Burn Reservoir was to be 143 million gallons, between the top water level and the limit to which, in consequence of the opposition of the papermakers on the Carron, they were allowed to draw it down – viz 10ft below top of the water level. The conduit between Faughlin Burn and Little Denny reservoirs was to be partly 14-inch and partly 15-inch diameter cast-iron pipes, capable of conveying at the rate of 3,860,000 gallons in every 24 hours. From the filters at Little Denny to Dunipace Bridge, the main pipe was to be 16 inches in diameter, capable of conveying to that point at the rate of 1,689,000 gallons in 8 hours. From Dunipace Bridge to Falkirk, the main pipe was to be 14-inch in diameter, giving a discharging capacity at the rate of 630,000 gallons in 8 hours. From Dunipace Bridge to Stenhousemuir, the main pipe to be 8 inches in diameter, delivering at the rate of 195,000 in 8 hours. From Stenhousemuir westward to the boundary of the Larbert water district at Carronshore, the pipe to be six inches in diameter, with a rate of 125,000 gallons in 8 hours. The alterations in the piping were estimated to add about £800 to the cost of the works. Branch piping to the value of £3,000 was required.

Seventeen bids were tendered before January 1889. At £48,460 the offer of D.Y. Stewart & Co of Glasgow was the cheapest for the whole works. If the work was divided up amongst the tenderers, as had been intended, it would increase the cost by £426, and therefore only a single contract was issued. Stewart & Co was a respected company and had done the work for the Dundee water supply. Activity began on site early in March with the erection of huts at the sites of the Earl’s Burn and Faughlin reservoirs for the accommodation of the workmen. The workmen for Little Denny were located in town. The first sod was officially cut on 2 April 1889 and Stewart & Co presented a silver spade engraved with the inscription:

“Presented to William Hodge, Esq, of Awells and Muiravonside, Provost of Falkirk, J.P., and Chairman of Falkirk and Larbert Water Trust, on the occasion of his cutting the first sod at Commencement of the water-works at Faughlin Burn, 2nd April, 1889.”

It was enclosed in an oak case, with blue silk and velvet lining. As the ceremony took place in an isolated location a luncheon was provided for the Trustees and their guests – an extravagant affair with plenty of drink which brought forth irate criticism from the public.

The work proceeded well. The material for the Earl’s Burn embankment was both easily reached and suiting the purpose well, and clay was also being got that was likely to make good puddling. Mr Bowser, of the firm of contractors, seemed to think he would get through his work even within the two year time specified. Amazingly, the pipes cast at Carron fifty years before for the old reservoir were found to be good enough to be used again. At Faughlin Burn the work ground was dry and good soil to work on. At Little Denny reservoir, which was the principal part of the work, everything seemed to be going on well also. By June there were nearly 400 men employed altogether, along with 44 horses. To maintain order a works’ policeman was appointed. Amongst his jobs was the turning out of the men from the public houses at closing time. An idea of the scale of the operation can be had from the fact that by 25 July 1,168 tons of pipes had been cast and passed by the inspector – that amounted to 2,564 lengths of pipe making 134,000yds in all. Altogether the scheme was expected to require about 4,000 tons, or 25 miles, of cast-iron piping of various sizes from 24 inches to 3 inches in diameter.

By the beginning of October about 400,000 tons of material has been shifted for the construction of the embankments. The road at Faughlin Burn has been diverted and the 200ft wide base of the embankment lain by the 106 men there. Around 50 men were employed on the Earl’s Burn Reservoir. At Little Denny reservoir about 126 men and 33 horses were employed, besides 64 men at the filters and 24 on the pipe track. The enormous embankment there was about half way up. It was 1,160 ft in length, measuring 500ft broad at the base, and would eventually taper to 13ft 6in at the top.

The lack of suitable building stone in the vicinity of the works meant that more concrete was used than originally planned, but Copland gave the go ahead. The use of this material on a large scale for such public works was still in its infancy and inevitably caused problems when the workmen failed to wash the stone used in it properly. In January 1890 it was discovered that the concrete at Faughlin had been made of rotten rock and it gave way. It should have been crushed whinstone, washed and clean. This was said to have been due to an individual workman. However, it was found that the concrete at the Earl’s Burn Reservoir was also giving way.

The project was well ahead of schedule but Copland does not seem to have monitored the works well and in January 1890 a leak was observed at the Earl’s Burn Reservoir. It had to be determined whether the water was coming through the rock or the puddle wall. Already apprehensive, rumours spread rapidly amongst the public. At the end of February it was widely canvassed that one of the receiving tanks at Little Denny had burst, and that the pipes in several places between Faughlin and Little Denny had also burst and were leaking. Councillor Cockburn, convener of the Works Committee, in company with Captain Dobbie, Councillor Johnston and Mr Wilson, the town clerk, proceeded to Little Denny, and there, and for a considerable distance along the train of the pipe from Faughlin made a careful examination of the work. All that they discovered were three slight leaks in the pipe which had been caused by “over-driving” the joints. These were quickly lifted and renewed. The defective concrete at the Faughlin Burn byewash was renewed in May and the following month so was that at the Earl’s Burn Reservoir.

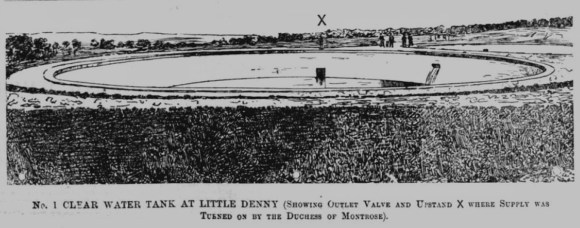

In late June the contractors sent word to the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trust that the work had been completed and shortly afterwards the engineer certified it. A site for the cottage proposed to be erected for the waterman who would be in charge of the reservoir and tanks at the Faughlin and Little Denny reservoirs was selected and it was proposed to have telegraphic communication between the works and headquarters. The water was officially turned on amidst great ceremony by the Duchess of Montrose in late July 1890 and was extensively described in the pages of the Falkirk Herald. David Ronald also mentions the event in his diary:

“The opening of the Water Works in 1890 was a great day in Falkirk. Triumphal arches were erected, flags put out, and there was a procession from the Town Hall via Camelon Road, Larbert, Stenhousemuir, Carron, Bainsford, and back to the Town Hall. I did not see it myself. Every organisation was represented. Among them, the butcher Jimmy Ferguson… One story I was told was about the Clerk’s nephew Neilson, who was firemaster and headed the procession with members of the fire brigade. These cleared the crowd so that the Duke of Montrose, who opened the Works and the procession generally, could get a passage. He was riding on a white horse, which he could do very well, in his fire brigade uniform that he rarely wore, and on his tunic there was a shining whistle, which gave a peculiar sound. This was attached to his tunic by five or six strands of light coloured chain hanging in loops over his breast. The Captain of the Brigade wore a brass helmet and his uniform, and the firemen had black helmets with less decorative tunics. They were all on horseback. The story goes that when the procession reached Bainsford Canal Bridge some old wives from John Street, a pretty rowdy quarter in those days, were standing on the street with their arms folded in their aprons. One said to the other when they saw the white horses prancing across the canal bridge “Oh, here’s the Duke”, and as they came nearer another women said “it’s no the Duke at a, it’s the dirt men”.”

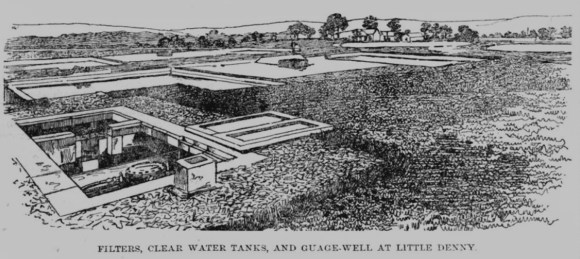

The construction project had been massive in scale and importance and so the main components of the completed works will be described here.

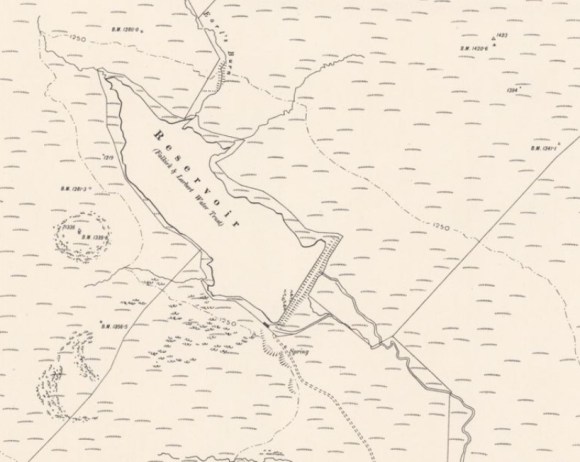

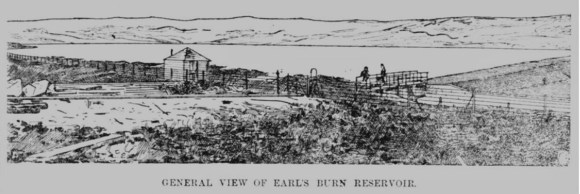

Earl’s Burn Reservoir

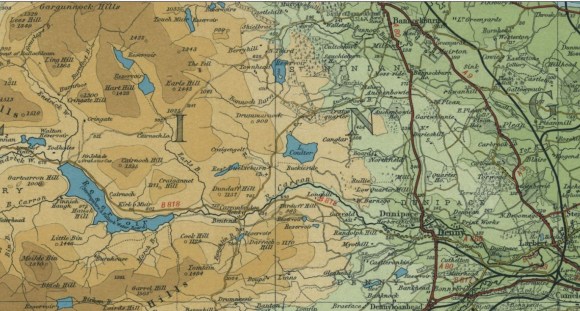

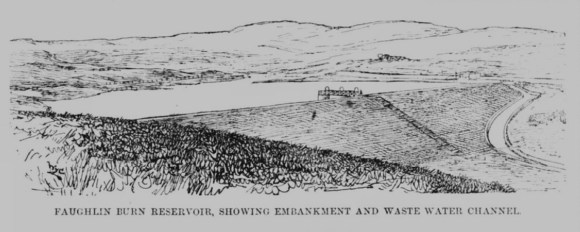

The reservoir for the storage of compensation water was situated on the Gargunnock Hills near the source of the Earl’s Burn, one of the main tributaries of the Carron, at a distance of 15 miles from Falkirk, and at an elevation of 1,205 ft above sea level. It was on the site of an earlier reservoir. The area draining into it was about 600 acres, and the reservoir occupied 90 acres, and could store about 250 million gallons of water. The embankment was only 1,329ft long, with a maximum height of 22ft and width at base of 140ft. The compensation water was measured by passing it through a gauge well at the outside of the embankment before it discharged into the stream. The accompanying contemporary illustration was taken from the rising ground at the west end of the embankment and conveys an idea of the large sheet of water and the extent of the work. The old embankment had to be cleared away, and more stable foundations found. Excavations, to the extent of 6,468 cubic yards, were made, including a sufficient cutting into the solid whinstone and filling up with puddle clay to afford complete security. The embankment was composed of about 7,000 cubic yards of clay puddle, 15,000 of earthwork, and 4,000 tons of stone in pitching, beaching, and broken stones. Great difficulty was experienced in finding puddle clay in the locality and rock suitable for pitching, and the expense and trouble connected with conveying these to the place by carting over rough moorland roads was considerable. Indeed, for nearly two miles of the distance a road for the purpose had to be formed. The waste water channel was in line with the old one, but as the latter had been nearly filled up with moss, excavation to the extent of 2,929 yards was necessary.

The massive new channel was wholly composed of concrete and was designed so that when the water in the reservoir reached a point four feet from the top of the embankment, the overflow would be carried off by it to the course of the burn, and thence to the Carron.

Faughlin Burn Reservoir

This reservoir is situated a short distance above Carron Bridge, on the east side of the Kilsyth Road. The supply of water was taken from the Faughlin Burn, a small tributary of the Carron, situated about 11 miles from Falkirk and about 5 miles from Denny. This stream, above the point where it was intercepted by the construction of the dam, drained an area of 1,010 acres, and yielded an abundance of excellent quality water. The average yield during the driest years was put at the rate of 1½ million gallons per day. The embankment forming the reservoir was 630ft long, and of a maximum height of 38ft, and width at base of 180ft, the top water level being 733ft above the sea. The reservoir thus contained, when full, 32 million gallons of water and occupied 22 acres. The method of construction was much the same as that adopted at Earl’s Burn. The lie of the land allowed the embankment to be constructed from one side of the valley to the other. A large amount of excavation was necessary to provide space for the storage of the water, and the road had to be diverted and a new bridge erected. In all 6,886 cubic yards of material was excavated, of which 1,009 consisted of rock. The deepest part of the puddle trench was excavated to a depth of 30 feet into the rock.

The embankments contained about 45,000 cubic yards of material, the puddle clay alone being 5,000 cubic yards. The stone work required at this reservoir amounted to nearly 7,000 tons and 801 cubic yards of concrete were used in the construction of the waste water channel, upstand pipe, culvert, and so on.

Pipe Between Faughlin and Little Denny Reservoirs

The reservoir at Faughlin was not large enough to contain as much water as was necessary for the supply of the town and district, and consequently the water was conducted from the small reservoir by a conduit, consisting of cast-iron pipes, partly 14-inch and partly 15-inch in diameter for a distance of five miles to a point in the valley of the Little Denny Burn, a mile above the town of Denny, where a larger reservoir was constructed. 382 tons of the 15-inch pipes were used, and 826 tons of the 14-inch pipes, while there were 25 tons of special pipes, making in all 1,233 tons. The cast iron pipes were laid for a distance of 4¾ miles. Among the more difficult parts of the work was the crossing of the Castle Rankine Glen, where the pipes had to be led down one side to the bottom of the glen and up again on the other. The piping passed through the moor east of the Faughlin Burn reservoir, along the road for half a mile, then though the wood above the ruin of the Hermitage, through the fields along the valley of the Carron, and out on to the road at Graywalls Farm. From there the pipe was laid along the road to Cummocksteps Bridge, which had to be widened to allow the pipe being laid across it. It then entered the fields at Fankerton, and from a point on the shoulder of Myothill it pursued a straight line to the Denny Reservoir. On the way two lines of railway had to be crossed.

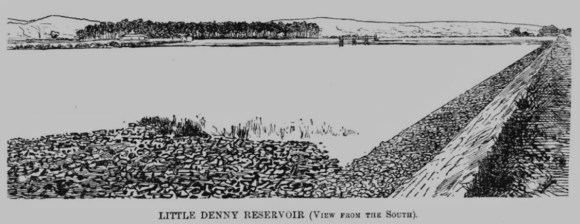

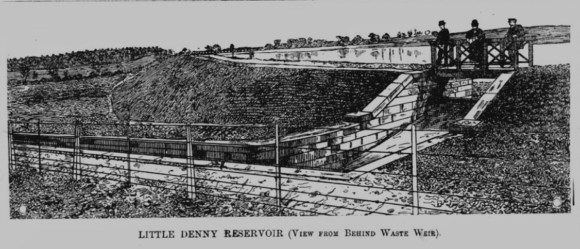

The Little Denny Reservoir

This was capable of storing 126 million gallons of water and covered 55 acres of land. The conduit leading to the reservoir was capable of passing down at the rate of nearly four million gallons of water a day. The embankment of the main reservoir was 1,550ft in length, and of a maximum height of 48ft on a base 250ft wide.

The top water level was 315ft above the ordnance datum. As the Water Trust did not seek or obtain powers to impound the poorer quality water of Little Denny Burn, that stream was passed round the outside of the reservoir by means of a 24-inch diameter pipe conduit, discharging into the byewash of the reservoir at the outside of the embankment. The diversion of the Little Denny Burn and the formation of the waste water channel took 191 cubic yards of concrete, 1,534 cubic feet ashlar cope, and 364 cubic yards rubble masonry. The execution of the whole work at the Little Denny site necessitated the stripping of 4¼ acres, and the excavation in connection with the puddle trench, waste water channel, & c, of 6,924 cubic yards. The embankment consisted of 12,600 cubic yards of puddle clay, and about 100,000 tons weight of earthwork, broken stone, pitching, & c.

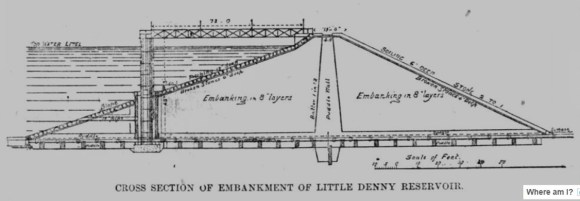

The Reservoir Embankments

were all formed in a similar way, as shown in the section. A puddle wall runs along the centre of each, the trench, made for its construction, being 4ft wide at the bottom, increasing in width to the top by a foot for every 4ft in depth, and was excavated until a water-tight foundation was reached either in rock or clay, after which it is filled up solidly with clay puddle, thus forming the puddle wall which was carried to within 10 inches of the finished level of the embankment or 3ft 2ins above top water level. It was 4ft in thickness at the top increasing in thickness according to the height of the embankment above the original surface of the ground at the rate of 1ft in every 6ft of height. The embankments themselves were formed of earthwork put down in regular layers, the width at the top being 13ft 6ins with a slope to the outside of 2 horizontal to 1 vertical, and to the inside of 3 horizontal to 1 vertical up to top water level. At the Earl’s Burn Reservoir, on account of the material forming the embankment not being quite so good, and the risk of damage by storms being greater, a slope of 5 horizontal to 1 vertical was adopted for the inside face.

After the embankments had been brought to the proper shape, a 4-inch layer of broken stone was spread over the outside slope and the top, and over this again a 6-inch layer of soil. The inside slope was finished first with a 6-inch layer of broken stone, and on top of that with hand-set rubble stone pitching 12 inches deep. Owing to the difficulty of obtaining suitable building stone in the neighbourhood, concrete were largely adopted at the Earl’s Burn and Faughlin Burn Reservoirs – the upstand towers, the waste weirs, the waster water channels, the gauge wells, and other works being of this material.

The Upstand Towers

in which were placed the valves for drawing off the water, were circular, and of 10ft external diameter, carried up to the level of the top of the embankments, and connected with them by means of light wrought-iron footbridges or gangways. At the Little Denny Reservoir the upstand tower was constructed of massive cast-iron cylinders, 5ft in diameter and provided with valves to draw off the water at four different levels. The depth of the reservoir was 44ft and so long as there was more than 33ft of water, the supply was drawn from the upper valve. If the level fell below 33ft it was to be drawn from the valve placed at 22ft from the bottom; when the level fell below 22ft it was drawn from the valve 11ft from the bottom; and when the level fell below 11ft, or when it is necessary to sour out the reservoir, the bottom valve was to be opened. This arrangement admitted of the best water, that is the upper portion, being utilised, and prevented unnecessary fouling of the filter beds.

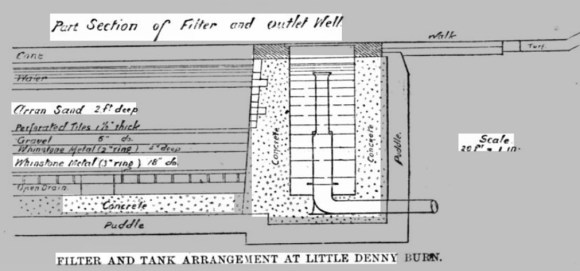

The Filter and Clear Water Tanks

were situated near Little Denny Farmsteading, and the six acres of ground allowed for future expansion. The 1890 layout consisted of four filters, each 75ft long by 45ft broad, and each capable of passing 250,000 gallons of water every 24 hours, and two circular tanks for the storage of filtered water, each 100ft in diameter by 11½ ft deep, the two together being capable of containing one million gallons of water. The tanks were situated at an elevation of 254ft above sea level, and the filters 2ft higher. The bottoms of the filters and tanks consisted of concrete, faced with white enamelled bricks, finished on top with ashlar stone copings, and lined at the back with 1ft in thickness of clay puddle. The water coming from the reservoir entered the filters near the cope level, and passed downwards, first through a layer of Sannox Bay sand 2ft in thickness, then through a layer of fire clay tiles, perforated with holes 1-10th of an inch in diameter, then through 6 inches of fine gravel, next through 4½ inches of broken whinstone, and lastly through 18 inches in thickness of ordinary whinstone metal such as is used on macadamised road. In the bottom of the filters, formed in the concrete, was a main drain leading to the outlet chamber, and a series of branch drains or arteries to receive the filtered water. In the outlet chamber, an arrangement was adopted to regulate the speed of filtration. This consisted of a telescopic pipe formed of gun-metal, the mouth being upwards, and which could be raised and lowered. Two machines were provided for washing the sand when it became foul.

There was also a gauge well and a clock and self-recording instrument, which graphically showed on a diagram sheet placed on a drum the quantity of water passing at all times. The drum revolved once in every 7 days, and so the sheet only had to be changed once a week. The conduit between Little Denny Reservoir and the filters consisted of 12-inch diameter cast-iron pipes.

The work here included the stripping of nearly two acres, the excavation of 10,889 cubic yards, 2,300 cubic yards of puddle, and the laying of 660 lineal yards of turf. In the formation of bottoms and walls of tanks and filters there was 2,095 cubic yards of concrete work, and in the walls 1,400 square yards of white enamelled brick. The filtering material consisted of 750 cubic yards 3-inch whin, 188 cubic yards 2-inch whin, 250 cubic yards gravel, 1440 square yards perforated tiles, and 1,250 tons of Arran sand from Sannoc bay. There have been used 598 lineal yards of cast-iron piping, ranging in sizes from 16 in to 4 in, and 500 lineal yards of fireclays pipes ranging from 4 to 15 inches in diameter. There were also 36 valves of various dimensions in this section of the works.

Line of Piping –

from the clear water tanks at Little Denny to Dunipace Bridge, at which point the supply to Larbert was taken off, the conduit was of 16-inch diameter cast-iron pipes. From Dunipace Bridge to Falkirk the conduit was of 14-inch diameter pipes,; the main pipe to the Larbert district being 10 inches in diameter as far as Stenhousemuir, 8 inches in diameter from there to Carron, and 6 inches in diameter from Carron to Carronshore. Taking the water main under the Forth and Clyde Canal at Camelon should have been difficult but the canal engineer granted permission for the 24-inch pipe to be carried through the pend by which the main road formerly passed under the canal at Camelon Bridge. A chamber was been built at either side of the waterway so that the pipe could be inspected or repaired at any time without interference with the canal.

Earl’s Burn Reservoir Reconstruction

As usual with any major project of this nature there were snagging problems. A slight leak was detected at both the Faughlin Burn and Earl’s Burn reservoirs, some pipes appeared to be burst, and a rent appeared in one of the clear water tanks. It was found necessary to raise part of the embankment of the Earl’s Burn dam on an average nearly 30 inches – the old original embankment upon which the new one was built in that section having subsided with the ponderous weight – and 24 men were employed at the job. New sleeping and store accommodation had to be provided as the huts used during the original construction had been sold off. Then it was found that the leak at this site was more serious than Copland, the engineer, had admitted. Mr Reid of Leslie & Reid, civil engineers in Edinburgh, was asked to examine the embankment, and Mr Watson of Bradford also made a report. Holes were opened up to investigate and it was discovered that the clay used in the puddle wall was of questionable quality. William Neilson had complained about this during the construction, but had been overruled by the engineer. Now the worst leakage was from that part on which Neilson had made most complaints. Copland was invited to inspect the work, but seems to have been more concerned with his own reputation and fortunes than about the work that he had overseen for the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trust. The contractors denied all responsibility and said that the work had been executed in accordance with the contract. Money due to them was initially held back by the Trust. Mr Hawksley, C.E., London, was consulted and Mr Gale was asked to arbitrate.

Leslie & Reid were then asked to draw up plans for the reconstruction of the reservoir and considered it best to make a brand new embankment a little out from the existing one. With engineers’ fees and so on, they estimated it would cost almost £10,000 – money the Trust did not have and which it was loathe to approach Parliament for another Bill to procure. As often happened, William Neilson came forward in April 1893 with a cheaper affordable alternative which involved incorporating the sound part of the existing embankment into a new one. This, he estimated would cost £2,300. James Wilson, C.E., of Greenock was appointed to look over these plans. More bore holes were dug to find the depth of the rock and Wilson produced a plan of his own. He suggested that in addition to the work proposed by Neilson, the two ends of the damhead should be tied into the valley sides and this took the cost of the proposal to £5,500.

On 18 September 1893 William Black C.E. was instructed by the Works Committee of the Trust to examine and report upon the plans and proposals of Leslie & Reid, Mr Gale, Mr Watson, Mr Neilson, and Mr Wilson, all of whom had made proposals as to the best method in which the embankment might be reconstructed. The plans suggested by Leslie & Reid seemed to him to incur an unnecessary expense. The proposals of Mr Watson and Mr Wilson, he stated, resembled each other pretty much, the former proposing a new puddle wall parallel to the old, and 38 feet out, and the letter proposing a puddle wall 38 feet out in the centre, and converging at both ends to the existing puddle wall. Mr Neilson, on the other hand, had proposed to form a new puddle wall 24 feet out from the present embankment at the two weakest points, while at the north he proposed a new puddle wall parallel to and close behind the existing wall, and at the south end, and between the two weak points, he proposed to utilise the existing puddle wall for a length of 590 feet, and to raise it to the top bank level with new puddle. Mr Neilson also proposed for this length of 590 feet to place a second puddle wall at the tail end of the slope next the moss. The difference therefore between Mr Neilson’s and the three plans mentioned was that whereas the latter showed a new puddle wall throughout the total length of the embankment, Mr Neilson proposed to make use of a portion of the existing puddle wall – a portion, which from its strong and durable nature, seemed capable of being made use of. Mr Black in his report made a proposal for the reconstruction of the embankment, which, to a certain extent, adopted portions of the proposals of Wilson, Neilson, and Watson. This was accepted, and Black was appointed the engineer, and Neilson, superintendent, was appointed to supervise the work.

The work was put out to tender and the offer of £3,368 by Alexander Stark & Son, contractors, Kilsyth, was accepted. The work was commenced at the beginning of the May and was anticipated to take four months, but due to deviations from the plan as a result of further problems being found the period was extended.

Investigations had already shown that good clay for the puddle could be had nearby on McGrigor’s land, and the contract included digging it and restoring the ground afterwards. In order to convey the puddle the contractors constructed a light railroad from the puddle-hole to the works, and used wagons. This did away with the need of carting and prevented the soil from being cut up too much. Several “commodious and comfortable” huts were erected for the convenience of the workmen engaged, of whom there was a large number, while a blacksmith’s and cartwright’s shop was constructed for the purpose of making all repairs on tools, wagons, etc, that might be required (Falkirk Herald 17 November 1894, 5).

That things were not so idyllic as the newspaper suggests can be seen from David Ronald’s memoirs:

“The conditions of the navvies, who were principally Irishmen, could not be described as anything less than dreadful. They were housed in wooden huts with beds above each other like a ship. The navvies slept, we were told, naked, with their clothes hanging over the rafter to avoid as far as possible the infestation of their clothes by lice. The hut-keeper made the beds with a forked stick. The men bought their food at a store owned by the contractor and from each, I have no doubt, he made a handsome profit. The food was cooked in a separate building on a hotplate. The men did their own cooking and had to stand near their pot or pan and never take their eyes off it. If somebody had money enough to buy tasty bits, and he turned his back for a moment, the articles were whipped out of his and put into another man’s pan, who probably had no money to buy sausages or some other article. Then a fight ensued. There was a policeman constantly at the works and he had to be called in to quell the fight. I never heard of his arresting anyone. He dealt with them himself by using his baton freely. When these huts were finished the contractor did not take them down. Paraffin oil was put on the floors – there was no petrol in those days – and a light was put to them, and it occurred to me when one of these huts was burning that many thousands must have perished in the flames.

Among the miscellaneous workmen it was discovered that one was a stickit minister, two were broken down medicals, another fellow could do calculus, though we never found out what his profession was.

We never had much dealing with the navvies. You could not be too familiar with some of them, as there was no saying what they would do with you when they were under the influence of drink. They were a wild and lawless lot and sometimes after a dismissal the man would turn up again in a month or so, but under a different name – you never could be quite sure what a man’s proper name was.

There was one very wild fellow called ‘fighting McCue’. We were told he had been in Stirling on a Saturday afternoon and Sunday for the usual drinking spree. He returned home from Stirling over the hills and came back with a fine pair of new boots. He was questioned by the policeman as to where he had got the boots; the latter thinking it might be the clue to some housebreaking episode in Stirling. McCue explained that he had bought the boots and paid for them. Some weeks afterwards someone was returning by the same route over the hills from Stirling and came across a man lying dead in the heather. He had been lying for some time and his feet were drawn away from his ankles and lay apart with socks on them. Nearby was found a pair of old boots. The navvy who found the dead man reported the find to the police, and on investigation it was found that the boots lying near the dead man belonged to McCue. He had pulled the boots off the corpse and in doing so had pulled the feet off with the boots. Having removed the feet he put on the boots and arrived triumphantly in camp with the story that he had bought them in Stirling. Such was the dreadful life of the navvy.”

This time the work was well executed and was completed in early December 1894. It was July the following year before Provost Griffiths laid a final stone which has been presented by Alexander Marshall, builder, bearing the following inscription:

“This stone was laid commemorate the reconstruction of Earl’s Burn embankment, 24th July, 1895, by Provost Griffiths, chairman of Trustees.”

The presentation trowel was of solid silver with an ivory handle, and bore the inscription:-

“Presented to Azariah Griffiths, Esq., chairman of the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trust, on the occasion of his laying the final stone completing the repairs on the embankment at Earl’s Burn Reservoir, July, 1895.”

The oak mallet had a silver shield engraved with the Falkirk coat-of-arms, and on the silver top of its ebony handle was the Provost’s monogram. A good use of public money!

The Provost also had other perks. David Ronald was amused to note:

“The Water Board at that time was composed of the Falkirk Town Council and I think with either two or four members from Larbert representing ex-burghal interests. Provost Griffiths was Chairman of the Water Trust. He was also Managing Director of the Bonnybridge Silica and Fireclay Co, a flourishing business then. The Provost was a great fisher and he used to bring his rod when the Works Committee of the Water Trust came up periodically to inspect the progress of the works. They did more than that by way of refreshment. He used to go out for half an hour or so and get one or two trout. I said to him one day that if I happened to be at the reservoir and he could let me know, I could catch a few for him the day before. He accepted the idea, and in due course I arranged a riddle with screws which could be fixed to the outlet of the scour pipe of the reservoir, and by opening the scour the water got through but not the trout. The water was then shut off, and the riddle taken off and held, so that the trout came down the pipe and went into the riddle. I fished out a dozen or so of the best fish and put the rest back into the reservoir. This of course was done in the late evenings, after everyone had left the works. The fish were put in a sack, most likely a washed cement bag, carried along the south side of the reservoir and left in the heather. When the Board members arrived next day the provost went out for his fishing as usual and I went with him. The trout had been hidden at a spot, which could not be seen from the hut where the Trustees were ‘refreshing’ themselves, and when fishing along the bank we came to this spot. We dipped the sack in the water to wet the fish before the Provost put them into his basket. When we came back an hour or so later, he reported that he had had a most successful hour’s fishing. This happened on two or three occasions. Probably in after years this little bit of kindness had something to do with my being appointed Burgh Engineer of Falkirk…

On one occasion, when I was going to Earlsburn with an assistant who was a shooting man, we saw some blackcock on the stooks at Smallburn Farm (now submerged by the Carron Valley Reservoir). He, having a knowledge of the ways of the blackcock, suggested that we should lift half a dozen sheaves of oats, take them with up to Earlsburn and set them up near the hut. I did not know anything about blackcock, as we had none on our farms, although there were plenty partridges and pheasants. So we put some sheaves into our trap and set them up near the hut. He expected that in the morning there would be some blackcock on the stook and that he would be able to get a shot at them from his bed by opening a window. There was nothing, however. Next morning I was awakened by a shot and saw his bare legs disappearing out the window. He ran to the stook, picked up a bird and brought it in. One of the navvies had told us the best way to cook game birds was to clean them, leaving the feathers on, and put them into a ball of clay. The ball was then put into the stove and allowed to burn for a certain period – I forget the time – taken out and the clay broken off. We had plenty of clay for puddle and we followed this procedure in the evening and it worked perfectly. The feathers were calcined and stuck to the clay and the skin of the bird adhered to the burnt feathers. We allowed it to cool in the evening and had it to breakfast the next morning. It was a success and a change from bully beef or trout.”

A Disaster at Little Denny Reeservoir Averted

A dreadful gale blew up over the days around 11 February 1894. Its ferocity was greater in magnitude than any in the living memory of those at Denny. Fearing that the storm might do serious damage to the Falkirk Water Works, William Neilson and Provost Griffiths left Falkirk about three o’clock on Sunday afternoon and drove direct to the Faughlin Burn reservoir. On arriving they found that the water was overflowing the bye-wash to a depth of about 2 feet 6 inches. To relieve the pressure on the embankment Neilson had the scours fully opened. On returning to Falkirk at 9pm, Neilson telephoned to the Trust’s official in charge at Little Denny to open the scour in that reservoir. He afterwards left alone for Little Denny in order that he might be on the ground all night. The storm abated considerably between nine and ten o’clock on the Sunday evening. However it picked up again and at midnight. Neilson considered it necessary to remain at Little Denny reservoir until about 2.30am the next morning. At that time the wind blew a perfect hurricane. About two o’clock he was at the west weir examining the depth of water flowing over, and then proceeded along the embankment to the upstand pipe in company with one of the Water Trust’s men. So fierce was the gale that they were obliged to hold on to each other in order to perform the journey with safety. Despite their united efforts to keep on the top of the embankment, however, they were carried down its slope. The earth at certain places along the top of the embankment was gradually being washed away by the lashing of the water, and a channel had been made when the critical state of matters was discovered. Neilson left the embankment at three o’clock in the morning by which time the storm had greatly abated.

On returning to the reservoir about five o’clock Neilson found that a large slip had taken place upon a portion of the embankment, and water appeared to be coming from the reservoir about 5ft from the top of the embankment. It was not easy to ascertain, in the darkness of the morning, what was actually wrong, but at first sight he thought that at any moment the whole of that side of the embankment might give way. He immediately gave men instructions to cut the sill of the waste weir for the purpose of assisting to lower the water in the reservoir, and this was successful. At six o’clock Neilson phoned Mr Marshall, his assistant, to send men and a quantity of wooden piles to strengthen the embankment and to protect it from the force of the water. This was carried through as speedily as circumstances permitted. Neilson also phoned Provost Griffiths and Bailie Hamilton and on Monday morning they made an examination of the embankment. The Provost phoned Mr Gale, C.E., Glasgow, requesting him to be in attendance at the works as early in the day as possible and he was able to get there about 4pm. On reaching the scene, he advised that the water in the reservoir should be let down as quickly as possible, as the reservoir was not altogether free from danger.

The damage done to the embankment was considerable and Mr Gale advised that the embankment should be raised and the waste water weir widened. It turned out that Neilson had advised the Trust that a new puddle wall should be put up to strengthen the embankment at the very place where the slip occurred, but this work was not authorised, and therefore had not been carried out (Falkirk Herald 14 February 1894, 5).

David Ronald was involved in the aftermath of this incident, though his account of the event is somewhat different, as often happens with eye-witness reports:

“About January 1894 there was an incident that might have cost the water Trust an enormous sum of money. There had been a very severe frost and all the reservoirs belonging to the Water Trust were frozen, the ice being about 18 inches thick. Little Denny Reservoir, which has little or no gathering ground and is supplied with water from the Faughlin Burn Reservoir, has a burn on its north side which is diverted past it. The ice broke up with a sudden thaw and the waste weir, which is small, became choked with ice. The burn, part of which had been frozen also, became choked, and the burn flowed over into the reservoir. In a short period the reservoir filled up to the top of the embankment and overflowed. When the Waterman came up in the morning to inspect the dam he found water flowing over the top of the embankment. It was five feet higher than the level of the sill at the waste weir. He immediately rang up the Burgh Buildings and reported the condition. Mr Neilson was on the job at once, and took Mr Marshall, the Assistant Sanitary Inspector. By the time they arrived at the reservoir the back of the embankment, about fifty yards in length, had become sodden with the overflow. It had slipped and left the puddle wall of the embankment exposed on its outer face for a stretch of about twenty-five feet. Mr Neilson described it as something terrifying, only half the embankment holding up this huge volume of water.

Mr Neilson was a man of energy. Without a moment’s waste of time the water supply from Faughlin Burn Reservoir was cut off, and the scour pipe of Little Denny opened. The scour pipe is a pipe at the lowest level of the reservoir and is used principally for cleaning purposes; otherwise it is seldom used. Within a couple of hours he had men clearing away the ice from the waste weir and at a bend in the burn, and the water level in the reservoir began to fall. By next morning the reservoir was lowered to a level lower than the broken part of the embankment, and at that level it stood for about eighteen months until repairs had been carried out. Had the reservoir broken, as it might well have done, there would have been an enormous flood below the point where the flood waters would join the river Carron, and everything in its train would undoubtedly have been washed away…

The day after the catastrophe I had the opportunity of seeing it. It looked to me a terrible mess, but in those days I did not realise the gravity of the situation. We were sent in due course to measure up the extent of the damage, to take a great many levels and prepare plans and a schedule of quantities for the repair. My job was to hold the staff and read a chain.

In addition to repairing the damaged embankment the Water Trust decided, on the advice of their consulting engineer, to raise the level of the embankment by two feet and put a concrete cope along the top of the bank along the front edge. This necessitated the raising of the upstand, the place where all the valves are situated for drawing water from the reservoir.

In due course the plans, specifications and schedule of quantities were prepared and tenders invited. The lowest offerers for the work were a firm called Shanks and McEwan, and if I can remember aright the work was started sometime about mid-summer. This was the first contract this firm had had, but on enquiry the Water Trust found that one of the partners, McEwan, was a man with large experience and they decided they should get the contract. What pleased me most about this contract was that I was informed that I was to be more or less on the contract as a sort of engineer – clerk of works, and anything else that might crop up. I was greatly enamoured of the prospects in view. I had seen the Earlsburn Reservoir repaired and had a fairly good idea of what would be required at Little Denny.

It was a remarkable coincidence that the first contract which Shanks and McEwan executed was the repair of Little Denny for the Water Trust and the last, Carron reservoir, was for the Water Board. This covered a space of about forty years and during that period they had become a big concern and had executed many important contracts both at home and abroad. After the contract started I found that Shanks had had a dairy in Airdrie and had made a bit of money. He was probably like myself, wanted to get quit of cows and other animals. His partner, McEwan, who had just come from being travelling manager on the West Highland Railway to Mallaig, was a most experienced man, and he spoke Gaelic. He was always roughly dressed with a soft felt hat and leather leggings, just like a navvy ganger. Shanks, on the other hand, was a great swell. He had on, the first time I saw him, a lightish brown check suit with very tight trousers, brown leather boots, a fancy waistcoat of some kind, the buttons of which were of glass each one with a small picture of a milk cow. He had quite a massive gold chain. He wore a coloured tie, a sort of bunched up affair, which was popular at that time, and he had a glass pin in it with a narrow gold border and a small picture of a racehorse, and a brown felt hat with a narrow rim. They were both very nice men and I got along with them very well, particularly old McEwan who taught me many things.

The work of repairing the damage proceeded quite smoothly. The broken bank was first repaired and the reservoir was allowed to be filled to overflow level. The upstand at the gangway was raised and the concrete cope was cast at the work in boxes and placed along the face of the dam. My special instruction from Mr Neilson was to see that the face of the cope was in a dead straight line. This I did and he actually said it was “no bad”. I saw it many years afterwards and it was still in line. Each length of cope was dowelled with a slate pin and at certain intervals cardboard was inserted to provide for contraction and expansion. In due course the work was completed and measured up, and when the final measurement was made McEwan confided to me privately that they had made a profit of £1,200. He seemed very pleased. I had no idea in those days what a contractor’s profit should be, but I was learning.”

1896 Act of Parliament

The next Parliamentary Act in connection with Falkirk’s water supply was obtained in 1896, and gave powers to raise the embankment at Little Denny Reservoir 2ft, to raise the embankment at Faughlin Reservoir by 25ft, and to construct two new filters at Denny, and a new 14-inch main to Falkirk. The cost of the additions was £19,000. The raising of Faughlin Reservoir and the taking in of 300 acres of new gathering ground, was abandoned for a more elaborate scheme. The total expended on capital works from the 1888 Act to the Act of 1900 was £24,080.

David Ronald gives tells us of his part in the preparations for the 1896 Act:

“The Water Trust had begun to discuss the approaching shortage of water, the consumpt going up owing to the introduction of water to dwelling houses and an increase in demand for industries. They came to the conclusion that an extension of works was necessary. They appointed James Watson, the Water Engineer of Bradford who had formerly been at Dundee, to advise them. He recommended the building of a large reservoir on the site occupied by the present Faughlin Burn Reservoir. The Board adopted his recommendation and in due course three temporary assistants were added to the water staff, and the survey started. In those days the Ordnance Survey sheets did not have the contour lines showing the points of equal level. The first thing that had to be done for a new reservoir was to walk over the drainage area to ascertain the water shed and put in pegs at the point where the change in direction of flow of the water was estimated to take place.

On this survey were three new assistants, myself as apprentice, and two labourers as chainmen. This work was all new to me, and it was the first time I had seen the factors that had to be considered when a new reservoir was being designed. We lived at Carron Bridge Hotel, which was about half a mile below the Faughlin Reservoir. The staking out of the water shed took quite a time; weeks, in fact. The pegs had to be put in and afterwards surveyed by means of a theodolite. It was the first time I had seen this instrument used. By this means the survey was plotted or drawn out on an Ordnance sheet and the gathering ground of the reservoir was ascertained. The average annual rainfall was ascertained, and this, with the necessary allowance for percolation, evaporation, and compensation water, gave the quantity that would be available for storage.

I had many questions to ask and the senior of the three temporary assistants, John Whitelaw, gave me full explanations in the evenings at the hotel. In the course of about two months the foregoing information was completed. The site of the new reservoir was roughly pointed out by Mr Watson – it was to embrace the reservoir that still exists – and we proceeded to survey this. The reservoir was emptied, cross-sectioned and levels taken along these lines at intervals of, I think, fifty feet. These levels were plotted on to a plan and they enabled the capacity of the reservoir to be ascertained. The height of the embankment was then determined to give so many days storage in the reservoir, in this case about 160 days.

The survey went on and was completed about Autumn; then we were transferred to the office to prepare a rough set of working drawings and the Parliamentary plans, after which a Bill was to be lodged in Parliament asking authority to obtain the necessary powers to proceed with the work. This again was all new to me, and I enjoyed every minute while engaged in the work. Whitelaw was an expert on this, and used to give me long lectures in the evenings on the design of new reservoirs. The plans were completed ready for the lithographer but the Water Trust decided not to proceed with the Bill. They decided that they would make an application to Parliament for authority to take water from a small loch north of Carron Bridge called Loch Coulter. This proposal was also abandoned and was not utilised till years afterwards. Prior to the Bill which they obtained for the existing water works they had made an application to take water from this loch, about seven years previously. That was the first Water Bill for Falkirk, in 1888, but they lost their order owing to the opposition of the Laird of Sauchie who had, and still has, a trout hatchery which supplies young fish to clients far and near [see Calatria vol 3, 89-111]. Years after the Water Trust were successful in their second application and got authority to abstract the water from the loch with the necessary safeguard for a supply of water to the hatchery.”

1900 Act of Parliament and Drumbowie Reservoir

Further capacity was required and so the Trustees called in Mr Gale in 1900 and he recommended a scheme which would cost around £45,000. William Neilson believed that it could not be done for under £130,000. Nevertheless, an Act was obtained in 1900 for this work which included the construction of Drumbowie Reservoir, new high-level filters and tanks nearby at Blaefaulds, a new 18-inch main from Faughlin to Little Denny and Drumbowie Reservoirs, the addition to the gathering ground of 1,150 acres, and the construction of a catch-water drain. A new compensation reservoir on the Earl’s Burn was also required to provide water for the paper mills at Denny and the ironworks at Carron.

The reservoir at Drumbowie was needed in order to provide additional storage capacity, as that of the Little Denny Reservoir was limited and shortages in the summer months often led to the supply of water to Falkirk being reduced or even cut. The new reservoir was to be a little way up the valley of the Little Denny Burn from the existing one. This had the advantage of sharing resources, such as the new pipeline from Faughlin Reservoir, but also ran the risk that if the damhead at Drumbowie failed it could endanger the stability of the Little Denny Reservoir. The land was acquired and in the late spring of 1901 an agreement was reached with the owner of the mineral rights for the untapped coal reserves. The open water of the reservoir was to occupy a little over 36 acres, but it was necessary to acquire the mineral rights for a larger area to include the embankments and a buffer of 80ft amounting to 52 acres. The cost was £4,500, which was probably higher than it should have been as the coal would have been difficult to work. A buffer of 100ft had first been suggested but this would have made a considerable increase to the expense.

William Copland was appointed as the main engineer for Drumbowie Reservoir and a bore hole found bedrock at a reasonable depth. John Best of Edinburgh was appointed as the contractor. He was experienced in large projects, including some reservoirs. Work began in March 1902 and it was confidently predicted that the reservoir would be ready in a year’s time. The main task was to dig a large trench across the valley for founding the earth embankment of the damhead, but work also proceeded on the almost three-mile pipeline from Faughlin which had also been awarded to Best. The first month’s report was optimistic:

“During the month an average of 90 men and 8 horses were employed. During the first fortnight of the month the excavation proceeded in both ends of the deep part of the puddle trench, but during the latter fortnight the contractor’s attention was directed to a length of 30ft in the bottom of the valley into which he has sunk an additional 13½ ft, that is 57 ft from the surface of the ground. By doing this he has got through the soft rock into hard shale. During the first three weeks of the month they were proceeding with the excavation of the road diversion, but during the last week nothing has been done at it. Excavation is being taken out from the inside of the reservoir and embanked on the ground at the upper end” (FH 16 April 1902, 5).

There are hints here of problems to come. The trench was turning out deeper than had been anticipated and it looked as though the solitary borehole had actually hit a boulder which had been misinterpreted as bedrock. By the time of the next monthly report the number of men working on the trench had been reduced: