From its foundation, water for washing, cleaning and cooking in the town of Grangemouth was derived from the Forth and Clyde Canal. This was not unusual and as late as 1850 water was first taken from the Union Canal for Falkirk. The canal water may have suffered from the passage of vessels but at least it was not normally used to dispose of human sewage as were most natural water courses that passed through human habitation sites. In 1865-6 the Earl of Zetland paid for pipes to be laid from two miles up the canal in order to get it before it was polluted by the activities at the town, and so that it would have a small head of pressure. The water was coarsely filtered in the basement of one of the houses at the west end of Canal Street in what Porteous describes as a filter gallery. Three wells were erected in different parts of the town, and opened in April 1866. These operations were overseen by James Duncan, the factor on Kerse estate, and cost nearly £600.

For the buildings on the south side of the canal and at the New Town the water came from a “reservoir.” This is mentioned in the feu contracts with a clause stating :

“It shall not be understood that we [Kerse Estates] are to keep up and maintain the Reservoir on the south side of the Canal at Grangemouth or to furnish the feuars and Inhabitants with water therefrom but that it shall be in the power of the Superior to remove the said Reservoir and remove the pipes by which the water is conveyed whenever he shall think proper.” (Porteous 1994, 44).

The “reservoir” was the large basin used for storing timber and here the water was not filtered.

Three incidents connected with the use of this water may be mentioned.: About eight o’clock in the evening of 27 July 1813 a young woman was rinsing clothes in the timber basin when, it is supposed, some spars which she was standing on turned round and caused her to fall into the water unobserved. She was not missed for some time thereafter, and search being made in the basin, her body was found by her father at the bottom, under where she had been standing. Every means to restore animation was tried but without effect. Washing and fetching water was usually the work of the younger members of the family.

On 27 September 1828 it was a boy who went to take some water out of the canal. He fell headlong into the water and his struggles to regain the shore only carried him deeper into the channel and further from the reach of the people who assembled on the bank in an endeavour to assist. After rising once or twice to the surface, he sunk apparently to rise no more. At this critical moment, James Wyse, builder, Falkirk, who was engaged in the erection of some new works at Grangemouth Harbour, happened to see the crowd, and hastened to the spot. Without a moment’s hesitation, Wyse threw off his coat and hat and plunged into the water, dived to the bottom, and brought the boy up in his arms. “The vital spark, which had so nearly fled for ever, was soon recalled, and the boy restored to his delighted parents.” Animals as well as clothes were washed in the timber basin. In February 1851 a boy was drowned when he took his employer’s horse into the water and it stumbled, falling into the deeper channel.

Mr Burrell, the shipping agent, noted that when he arrived in Grangemouth in 1856 his old landlady used to go for water to the canal with an empty bucket in one hand and a slop-pail in the other, and she filled the former after having emptied the slops into the canal! The Easter Timber Basin was used for repairing barges as well as washing horses. Children also swam here, close to the intake pipe. Not surprising therefore that typhoid fever was rampant in Union Place in 1868. In the absence of sand or gravel filtering the consumers were advised to boil their water. Mutterings were made about adopting the Lindsay Police Act to allow a raised reservoir to be cheaply constructed at the site of the Orchard on the east bank of the Grange Burn. It would have utilised the existing banks which survived from the medieval grange and which can still be seen in Zetland Park. It had been thought that the water supply to Kerse House, which came all of the way from Tammy Mills Well in Laurieston, was at least wholesome, and the surplus was shared with some of the town’s residents. However, the piped water from Laurieston was analysed and found to be even more dangerous. Shortly afterwards the Earl of Zetland and the Caledonian Railway Co announced an intention to set up a Water Trust and explore the Earl’s land at Millhall for the source. Millhall is just over two miles south of Grangemouth on slightly elevated land.

Improvements in the town were difficult to achieve without a single authority in charge. There had been a long-felt need to improve the entire water supply and the lighting of the town and the senior citizens in the settlement believed that the best way to achieve them was by selecting clauses of the 1862 Lindsay Police Act and adopting them. The Burgh of Falkirk had already successfully instituted the Act and was able to display improvements. On 16 November 1872 the householders of Grangemouth had the opportunity to vote for or against the adoption of a set of clauses from the 1862 Police Act and did so, raising the town to the dignity of a burgh.

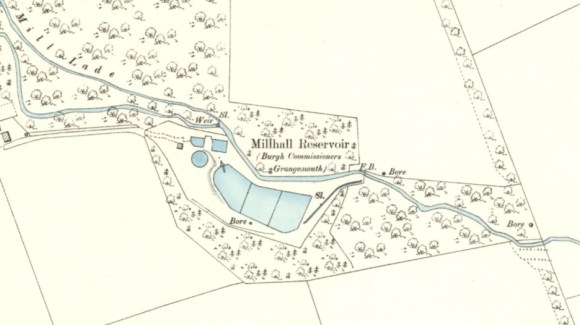

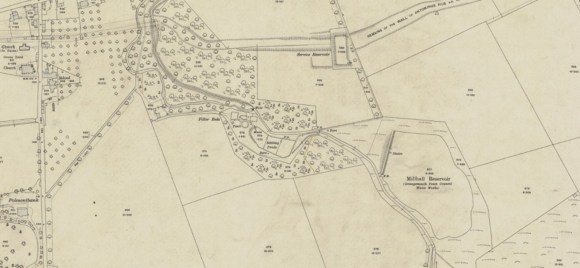

One of the first things that the Grangemouth Commissioners had to deal with was the water supply. The pipes laid for the Earl of Zetland had frozen in a bad winter and after the thaw no water came through. In February 1873 they commissioned Bell & Miller, civil engineers, Glasgow, to investigate possible sources. After a careful search they selected Millhall Glen and the working plans and sections of the three compartmented reservoir, clear water tank, and filters, to be formed there were presented in August 1875. The reservoir was to have an average breadth of 100ft by 300ft in length, with a depth of 6ft. The water was to be drawn off at a depth of 18 inches, so as to afford room for the precipitation of the organic matter. It was also to be provided with a hollow to scour it when necessary into the burn. The whole of the works were constructed on the ground of the Earl of Zetland, and the construction took around nine months despite the presence of quicksand. They were opened in September 1876 by Lady Zetland. At first sight it might be expected that the burn was to fill the reservoir, but it was so polluted that the engineers tapped local springs instead and supplemented them with bores from 150 to 300ft deep. The combined yield produced a steady flow of 75,000 gallons daily, providing 25 gallons per head of population. By agreement with the former landowner, the farms on the Zetland Estate were also supplied, despite being outwith the burgh limits.

Within ten years, in consequence of the rapid growth of the town, the water supply was woefully insufficient. In the summer months it had to be shut off for a number of hours during the night. In 1885 this period extended from 6pm until 6am, and even in August that year it was still turned off at 9pm. The mortality statistics for Grangemouth since the opening of the Millhall water supply clearly demonstrated that it had contributed significantly to longer life. It is therefore surprising that Grangemouth Burgh decided not to join the Falkirk scheme to obtain water from the Denny Hills.

Instead, in July 1885, reports were made on the springs at Avonbank, a mile to the east of Millhall, by Mr Leslie of Edinburgh, and William Black of Falkirk. The springs were analysed and found to be thoroughly satisfactory for domestic purposes. Negotiations were started with William Forbes of Callendar for land which was acquired at valuation. Thomas Learmonth Livingstone of Parkhall owned the neighbouring estate of Avondale which also had springs which were to be utilised, and wayleaves were acquired for the pipeline to Millhall. The works were built just to the east of Avonside Farm and consisted of a large tank or reservoir into which the water permeated through a filter, bottomed with fine sand from the island of Arran. The new works – tank, filter, pipes and so on – cost upwards of £2,000. To meet this expenditure the Public Loan Commissioners provided £2,500 and repayment with interest at 3.5% was made over the next 30 years. Considering that the old Millhall supply, consisting of 100,000 gallons per day, had cost the town £11,000, the expenditure of between £2,000 and £2500 for the new supply giving an additional 125,000 gallons per day, was very moderate. The work was carried out by Stark & Son, contractors, Auchenstarry, under the supervision of William Black.

The new supply was officially turned on by Hugh Macpherson, the Chief Magistrate, on 25 September 1886. He was presented with a silver key inscribed:

“Miniature key, presented to High Macpherson, Esq., Chief magistrate, on the occasion of his turning on the new water supply for Grangemouth, 25th September, 1886.”

It was the workmanship of Mr Callander, jeweller, Falkirk.

Illus: 1895/98 Ordnance Survey Map (National Library of Scotland).

One advantage of having the two separate works was that the water did require to be totally shut off whenever repairs and cleaning were necessary. The new supply was also 25-30ft higher and so gave a better pressure when the Millhall water was shut off. The higher pressure meant that it could reach the cistern in the third storey of a house which was the highest in the town. So the Millhall water was turned off in the evening. During the day the water never reached the cistern, but during the night it did so. It was also agreed that in the event of a major fire the Millhall supply would be cut off so that the hoses would be more effective. Before long it was found that the cast iron pipes between Avonside and Millhall gathered an accretion of iron on the inside, reducing their diameter and this had to be treated by extensive flushing.

Inevitably it was only a few years before the Grangemouth Commissioners were looking around for an additional water supply. Further up the valley from Millhall the burn was still considered to be too polluted but they found yet more springs at Gilston. By combining them they were able to gather 80,000 gallons daily and the water was piped to Millhall, being formally turned on by Hugh Macpherson on 10 November 1891. To cope with it an extra filter was constructed at Millhall. At 45ft by 33ft it was one half bigger that the existing one. R.B. Stewart of Saltcoats was awarded the contract and A & W Black of Falkirk were the engineers. Together with the cost of new and replacement piping the work came to £4,000. The town’s supply now consisted of:

| Millhall | 120,000 gallons per day | |

| Avonbank | 120,000 gallons per day | |

| Gilston | 80,000 gallons per day | |

| TOTAL | 320,000 |

The water now came in at an even higher pressure, helping those who lived on the upper floors of the tall buildings. It was also good for firefighting and so a fire plug was installed in front of the Town Hall.

To even out the supply to cope with the dry summer months it was obvious that a large storage reservoir was required, but it was 1894 before serious investigations were conducted. Leslie & Reid, C.E., Edinburgh, were called in and William Black undertook the necessary surveys. Mr Wilson was their project manager and eventually took over the firm. Land at Millhall and at Wallacestone was visited. That to the east of the existing works at Millhall seemed to offer the best topography and could practicably have a reservoir capable of containing about 10,800,000 gallons, or equal to 37 days’ supply. The bores in use at Millhall were too low lying to be used to fill such a reservoir and so negotiations started with the landowners in the area around. In May 1896 Black was asked to prepare plans and specifications for a reservoir to contain 15 million gallons (70 days’ supply) and soon afterwards agreement was made with the Duke of Hamilton’s Trustees and the Earl of Zetland for land. It was June 1897 before a loan of £5,000 at 3% interest was arranged with Macara brothers of Glasgow and construction work started. W.G. Fleck of Lenzie was awarded the contract and in August a puddle trench for the embankment was dug and started filling with water from a previously unknown spring. This new source was incorporated into the scheme and it was estimated to contribute 100,000 gallons daily. The Millhall Burn had to be diverted so that it would not contaminate the impounded water and it was found that the new course ran over fine sand, requiring concrete sides and bottom instead of the stone pitching originally planned. This added £100 to the contract. Provost Mackay opened the water supply from the new Millhall Reservoir and William Black presented him with a silver cup inscribed:

“Presented to Provost Mackay, Grangemouth, on the occasion of his turning on of the water at the new reservoir, Millhall, by Wm. Black, C.E. 27th December, 1897.”

In 1876 45,000 gallons per day were sent into the town, now the daily consumption was 220,000 gallons per day. The new reservoir enabled them to keep on the supply of water to the town continuously during the summer of 1898. By raising the overflow by a foot the following year even more water was stored. Black suggested deepening Millhall reservoir to increase its storage capacity but it was evident that something more drastic was required.

The Grangemouth Commissioners opened negotiations with the Eastern District Committee of Stirlingshire Council which was advocating a scheme at in the Denny Hills on the Buckie Burn. This initial approach was not very productive as the county council only offered to supply surplus water and the cost would be relatively high. This offered no security of supply and so Warren & Stuart, engineers, were asked to look for an independent source of gravitational water for Grangemouth. They suggested alternative sites in the Denny Hills at the head of the Carron and on the Bannock Burn. With their report to hand the Grangemouth officials again met with the representatives of the Eastern District Committee and this time they were more cooperative, especially as the Bo’ness Burgh was also offering its surplus water to Grangemouth. A quick aside led to an investigation of a site on the Callendar estates of William Forbes and showed it to be too expensive. So too was the Carron scheme. So now it was a straight choice between the Eastern District and the Bannock Burn schemes. By then the works of the Eastern District were in progress and were estimated to cost £107,590. Amalgamation with that scheme would require additional works to the extent of £9,600 and a joint trust would take over the whole liabilities and the outstanding Grangemouth debt of £17,695. This Eastern scheme would provide a daily supply of 966,600 gallons and as the county population would require 657,000 gallons, it left a surplus of only 309,000 gallons for Grangemouth. It was proposed to increase the embankment by 4ft, and thereby store an additional 38,000,000. The water would be taken to Millhall in a 7-inch pipe, but whenever Grangemouth’s maximum demand exceeded 300,000 gallons, or the county was unable to supply that amount, it would be necessary to construct a lower reservoir, which was embraced in the scheme capable of supplying 552,000 gallons per day additional. The cost of this extension was estimated at £38,000, including the pipe track to the works at Millhall. It was proposed that the joint trust should consist of 15 members – 10 from the county and 5 from the burgh.

Under the Bannock Burn scheme the reservoir would hold from 60,000,000 – 65,000,000 gallons derived from a total drainage area of 2,240 acres. This reservoir, after providing for compensation water at the rate of 200,000 gallons per day, would be capable of yielding for the supply of the town 400,000 gallons, and if a 9-inch pipe was put into Millhall, the pipe would be capable of venting at Millhall at least 514,000 gallons per day. The cost of this scheme, including the pipe line and reservoir, expenses of land, engineers’ and law expenses, etc, was estimated at £41,800.

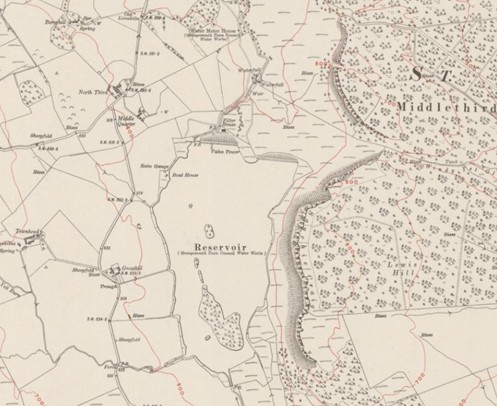

Proudly independent, it came as no surprise when Grangemouth went for the Bannock Burn scheme and put it before Parliament in 1903. In the meantime, water shortages at Grangemouth were so bad that around 1902 a pipe was laid from the reservoir at Millhall and connected to the Bo’ness main pipe at Linlithgow Bridge at a cost of £1,500. Bo’ness Town Council was well paid for the water taken. The Parliamentary Bill for the Bannock Burn scheme was opposed by the county, by millowners, and by some of the local estates, and so concessions had to be made. They were obliged to provide a maximum of 1,100,000 gallons per day to the stream as compensation water, 350,000 gallons per day for the Central District of Stirlingshire, and 150,000 gallons for the supply of populous places on Polmaise estate. The reservoir therefore had to be large enough to provide Grangemouth with the minimum of 750,000 gallons as proposed, plus 1,100,000 gallons to be sent down the stream per day, and 500,000 gallons for the Central District and Polmaise estate throughout the year. These commitments were heavier than anticipated and the engineers doubled the capacity of the reservoir and recommended a change of site to one upstream at North Third. The new site was put before parliament in the following session and power was granted to acquire the ground on the proposed new site. The engineers estimated the cost would now be £60,800, made up as follows:

| Storage reservoir, capacity 115 million gallons | £21,750 |

| 12-inch pipe, wayleave, etc | £31,120 |

| Parliamentary expenses, etc | £7,930 |

| £60,800 |

The first provisional Order gave power to take water from the stream during the construction of the reservoir, and in view of the straitened condition of Grangemouth’s supply and the large accounts payable to Bo’ness for water, the Town Council hurried through the laying of the 12-inch pipe, capable of delivering 1,100,000 gallons in 24 hours from the Bannock Burn at a point a little below the reservoir at Millhall. This part of the contract was expeditiously carried through, being completed in November 1905. The distance covered by the main pipe between the two places was about 18 miles. The pipes and valves alone cost something like £19,000, and the pipe-laying by contractors about £8,500, and added to that the cost of wayleaves, engineers’ fees, and so on, giving a total of slightly over £30,000, which was close to the engineers estimate.

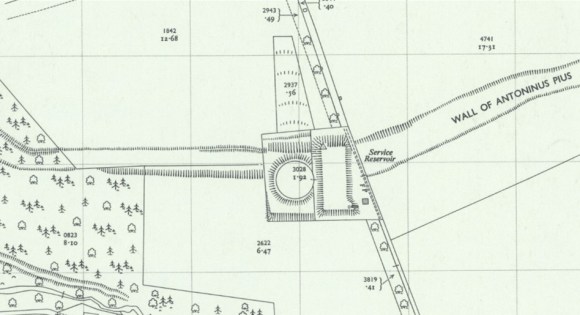

At this time the area covered by the Burgh of Grangemouth was extended, taking in the whole of the new docks, and the Burgh was compelled to take from the county a certain quantity of water at a price of £1,275 per annum. This was in consideration of the county having made provision to supply that area with water amounting to 200,000 gallons per day. A storage tank was therefore placed on the highest point at Millhall (on the line of the Antonine Wall), The tank had two divisions, each having a holding capacity of 502,000 gallons, and the county water was sent into these tanks, supplying Grangemouth, with a much higher pressure of water than ever it had before.

North Third Reservoir

On 27 October 1905 the formal cutting of the first sod for North Third reservoir on the Bannock Burn took place, performed by Provost Mackay. He was presented with a silver spade inscribed

“Grangemouth Waterworks, Bannock Burn Reservoir Presented to Provost Mackay on the cutting of the first sod on 27th October 1905. Warren and Stuart, engineers, Glasgow; Casey and Darroch, contractors, Glasgow; A.Y. Mackay, Provost; James Weston, Bailie; Edward Wood, Bailie; Robert Main, Councillor; John Gilmour, Councillor; Henry Walker, Councillor; J. Burnett-White, Councillor; James P. MacKenzie, Town Clerk.”

The reservoir is 3½ miles south-west of Stirling, and about 16 miles by road from Grangemouth. The area which drains into the reservoir site extends to about 2,300 acres, the two principal streams being the Bannock Burn and the King’s Yett Burn. The reservoir when fully filled held 400,000,000 gallons, and the area of the ground enclosed within the fence line was 118 acres. The greatest length of the reservoir is little short of a mile, and the greatest width is about half a mile. The top water level was at 553ft above sea-level, and the maximum depth of water was 42ft.

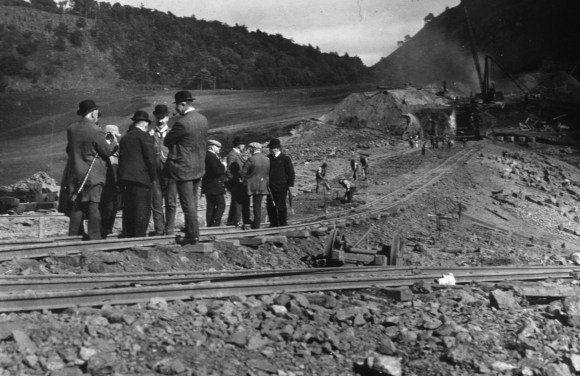

Work commenced on the construction of the road in August 1905 and on the reservoir in November. The work on the embankment soon encountered unforeseen problems which significantly increased its cost.

Three embankments were formed at the north end of the reservoir, the principal one being that across the Bannock Burn; the second or east embankment crossed a depression at the east side of the burn; and the third traversed a slight hollow to the west of the main embankment.

The site of the embankments for impounding the water was about half a mile from the public road leading from Stirling to Fintry by Cringate Moor. To enable materials to be taken to the works, an access road, half a mile in length, was constructed from the public road. This road crossed the Drumshogle Burn on an embankment about 20ft high over a concrete culvert about 100ft in length. A short distance below the reservoir embankment the road was carried over the Bannock Burn by a steel trough bridge.

They are all alike in construction, being formed of earthwork excavated within the reservoir, and having a core or wall of puddle clay in the centre, extending from one foot below the top of the embankment down to the bottom of the puddle trench, which was excavated down to an impervious stratum of rock. The puddle trench was continuous across all of the embankments and ran for about 640 yards.

The work of the excavation of the trench proceeded from November 1905 until the end of 1910. Borings taken previous to the contractors moving in had indicated that the greatest depth would not exceed 30ft. However, the whole area in the neighbourhood is covered with volcanic rock, beds of lava being intermixed with soft beds of volcanic ash, and it was these beds of soft ash that gave a great deal of trouble. The rocks above the thickest of the beds was found to be very solid and was sufficiently compact and close to have formed a foundation for the trench; but the ash bed below was not thoroughly watertight, and it was decided to cut through this bed into the solid rock underneath. The beds first encountered were all porous, but they had sufficient cohesion to stand with a plumb face after they had been excavated, although where they were exposed to the weather they disintegrated rapidly for a few inches in from the surface. Going eastwards, and getting further below the surface, they came much closer in character, and at certain points, where excavations were stopped, were considered to be impervious to water. In the excavation of the trench, work was started on the west side of the stream a few yards from the latter, and carried downwards and westwards. As soon as a depth had been reached to allow of it, a tunnel was driven under the burn, and simultaneously the sinking of the trench was started on the east side. The object of the tunnel was to allow the trench to be bottomed under the burn without disturbing the latter. The Bannock Burn frequently ran in heavy flood, and it was not considered advisable to interfere with the burn until other means had been provided for carrying the water across the line of the trench. A culvert 9ft by 9ft, with a semi-circular arch, was therefore provided off to one side for carrying it under the embankment, thus enabling the part of the trench over the tunnel to be excavated. The puddle trench at the widest part was 17ft at the level of the original surface of the ground, and this gradually narrowed to about 6ft at the bottom. Owing to the soft beds the trench had to be carried to a depth which varied from 35ft to 115ft, the average depth being about 75ft. The rock was of a particularly hard nature, and required to be blasted, and the greater the depth of the trench the wider it had to be made, besides being carefully timbered during these operations. In order to find out whether there were any further soft beds below the level at which the foundation was made, a series of bores were sunk, and these showed the existence of two further beds, which, however, were at a considerable depth below the bottom of the trench, and were found to be of a compact and impervious nature, so that there was no danger of the water passing through them. A field a short distance north of the embankment was used as the source of the clay to fill the trench. The puddling process was one of the most important parts of the undertaking and it was carried out under most stringent supervision both by the engineers and the Town Council.

The culvert used for carrying the Bannock Burn below the embankment was founded on the rock and lined with brick inside, surrounded with concrete. It carried the burn until the work was otherwise completed and the reservoir ready to be filled, when it was closed by a brickwork plug built at the inner mouth of the culvert. A pipe, 24 inches in diameter, controlled by a valve, was built into this plug for the purpose of emptying the reservoir at any time that might be necessary.

The culvert opened into an open channel at the outer end, 20ft wide and 4ft deep, which conveyed the water to the original course of the burn a short distance from the embankment. Another channel ran up from this one outside the tail of the outer slope of the embankment to take the water from the overflow of the reservoir.

This channel between the overflow and the channel from the culvert, owing to the steep incline of the ground, had to be stepped at close intervals to prevent the water acquiring too great a velocity. The overflow sill was placed 6ft below the level of the embankment and was 80ft long so that during heavy floods the water could pass over it without rising to a height that might endanger the safety of the embankment by waves washing over its top. A footbridge was carried over the sill at the level of the embankment.

The earthwork of the embankment was carried up in 6-inch layers which were beaten and watered to ensure thorough consolidation. The slopes on the reservoir side were dressed off to something like 3 horizontal to 1 vertical, and on the down-stream side of the east embankment to 2½ horizontal to 1 vertical. The slopes on this side of the east embankment were covered with good surface soil, and sown in grass seed, but on the reservoir side of the whole embankment it was protected by stone pitching laid on a bed of broken stones to secure them against damage from waves during stormy weather.

Over the inner end of the culvert a watertight valve tower of concrete, faced with stone, was built up to the height of about 12ft above the embankment, and an upstand pipe placed in the middle of this tower, with branches at different levels through the walls of the tower, so that water could be drawn at various levels below the surface. The valves on these branches were controlled from the valve tower, to which access was obtained from the embankment by means of a steel gangway, 73ft long, supported in the centre by a pier brought up from the top of the culvert. From the foot of the upstand pipe in the valve tower a pipe was laid through the culvert to the measuring house, from which the water was taken as required down through the main pipe to the tank on the hill north of Millhall.

A measuring house was erected at the foot of the slope of the western embankment, a little to the east of the culvert, containing measuring and screening chambers. The floors, compensation wells, screening wells, and inlet and outlet supply wells were all constructed in concrete. The supply to Grangemouth was fitted with two screening chambers, where it passed through copper wire screens of a very fine mesh. An iron runway above the screening wells, allowed the screens to be lifted with a light block and tackle, and then carried to a sump where they could be cleaned. While the screens of one chamber were being cleaned the water passed through the other chamber.

A waterman’s house was erected near the entrance to the works for the sluice-keeper to plans prepared by David A Donald, burgh engineer. It was built from the stone of the old farmhouse which had been situated on the site of the reservoir. It consisted of a board-room, a large kitchen with scullery and bathroom to the rear, on the ground floor; and, on the upper floor, two small rooms and one large bedroom. Adjacent to it were brickwork stables, a coach-house, bothy, and other offices. The whole complex cost about £1000.

By the time of its completion the total cost of the water works had risen to about £150,000. This included a payment of £500 to Stirling Town Council for the extraordinary traffic over its streets during the construction period. The official opening took place in June 1911 and was performed by the provost’s wife. The calculated yield of water for the town supply was about 2,200,000 gallons per day, as compared with 75,000 gallons per day with which Grangemouth was supplied from Millhall in 1876. Ironically, Grangemouth was now in a position to supply Bo’ness with surplus water, which it did at a good price. And later Stirling too took a large portion.

Within a few years there were complaints of the water from the North Third reservoir being dirty and this was put down to the erosion of its banks caused by wave action resulting from high winds. Indeed, the erosion was such that it threatened to extend the pond into neighbouring lands. More stone pitching was put in place.

It was partly due to the large surplus of water that Grangemouth was able to attract new industries, such as Scottish Dyes and Scottish Oils. In 1921 the Grangemouth and Stirling Water Order Confirmation Act resulted in Grangemouth Town Council retaining a two-thirds share in the North Third reservoir and the Stirling Water Commissioners taking a one-third share.

Inevitably the water usage increased and there was a supply deficit. The Grangemouth and Stirling Water Order Confirmation Order, 1932, gave authority to increase the capacity of the reservoir to give a capacity of 740 million gallons so that it would yield three million gallons of water per day. The height of the dam was raised in 1934 and again in 1936. It was probably a few years later that the large circular storage tank at Upper Millhall was constructed to the west of the existing tank in order to provide more storage at the right pressure.

It had brick walls and an open top. After the Second World War both Scottish Dyes (then Imperial Chemical Industries) and Scottish Oils (then the Anglo-Iranian Oil Co) undertook major expansions and required a far greater use of water. Fortunately, the Falkirk Water Act which led to the construction of the Carron Valley Reservoir by the Stirlingshire and Falkirk Water Board stipulated that Grangemouth was entitled to 2.5 million gallons from that source each day. More was needed and negotiations with that Board were presided over by the Department of Health for Scotland. The amount of water taken by Grangemouth was increased to 8 million gallons a day, which necessitated the construction of a new filter station at Broadside capable of processing 13 million gallons daily. Provision was also made for the construction of a covered tank at the bottom of Salmon Inn Brae near Grandsable capable of holding 3 million gallons and the installation of pipes from Broadside to it. Grangemouth Town Council paid eight-elevenths of the cost of the 13½ mile-long pipeline and filters as well as £20,000 per annum for the reservation of water in Carron Valley Reservoir. The agreement was for this annual payment to last for something like 41 years, that is, until the Water Board had paid off their loans on the existing Carron Valley works; thereafter the charge for water was to be a nominal one representing administration, maintenance and repairs. Until the filter station at Broadside and the new trunk main were completed in an estimated three years’ time, the Water Board made adjustments in its supply system to enable Grangemouth to obtain an additional supply of 1,000,000 gallons a day to meet the immediate needs of industries in Grangemouth. However, national restrictions on the use of labour and materials after the war meant that the project ran behind schedule and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company had to lend assistance. Materials, particularly the valves, were delivered late and often in the wrong order. Steel and spun-iron pipes had replaced the old cast-iron ones and it took some time for their use to be bedded in. Laying the main pipe to the Salmon Inn site was completed in mid-January 1951, but the contract for the tank there had not even been settled. A temporary arrangement was made to lead the water directly to Grangemouth from Salmon Inn. The service tank at Salmon Inn was designed to even out the supply to the consumers – the industries having peak periods of demand. It was also needed to reduce the water pressure and so during that initial period there was what was called the “water hammer” effect due to the sudden alterations that occurred in the flow, and this resulted in some damage.

The new service tank at Salmon Inn was designed by Babtie, Shaw and Morton of Glasgow, Grangemouth’s consulting engineers. It was situated on high ground to give the appropriate delivery pressure of the water. The reinforced concrete tank holds three million gallons of water to a depth of 16ft when full and was built into the hillside and partially covered by earth. As well as the storage tank there was a valve chamber. Outside, only the western façade was visible and Henry Wilson, architect, was asked to design it. It is typical of the period being of rendered brick with a horizontal line of blank windows and flat roofline. At the south end is a doorway set in an ashlar stone surround with the Grangemouth coat-of-arms to its left. On the door lintel is the date “MCMLII” being 1952.

Its construction had begun in June 1951 and was completed in March 1953. The official opening by Judge Penny was in July, by which time it had already been operating for several months. The construction operations at Salmon Inn had been a race against time in order to get water through to the Scottish Oils Ltd, for the start of their new refinery plant. As a result, raw water was first put through the scheme in February 1951. The filters at Broadside were finished in 1953, the Salmon Inn tank completed, and eight million gallons of water ensured. The cost of the valve chamber, storage tank and distribution pipes was £310,000, and the Town Council’s share of this sum was £240,000. The Council’s share of the cost of the Broadside Filter Station was £280,000, and in addition they were paying the Water Board £20,000 per year for the water.

Also, as part of the Burgh of Grangemouth Augmentation of Water Supply scheme a contract was issued towards the end of 1953 to repair and roof the circular tank at Upper Millhall. A reinforced concrete lining was placed over the floor and walls and a small valve camber inserted. Further improvements had also been made to the reservoir at North Third to provide better filtration, and in 1951 an automatic chlorinating plant was fitted.

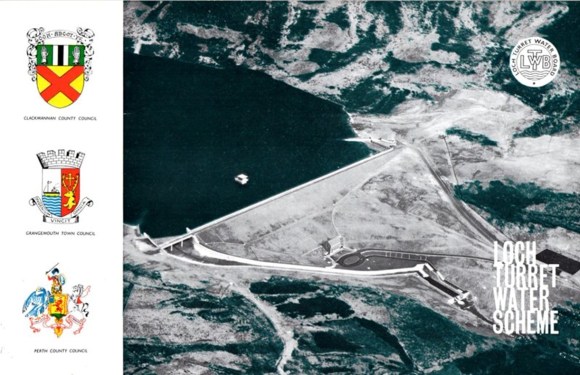

So, since 1876 Grangemouth Town Council had seen the implementation of water schemes at Millhall, North Third and Carron Valley. Each time it claimed that there was sufficient water to last a generation and each time more was required within a few short years and such was the case in 1955. Accordingly, it commenced meetings with the Interim Loch Turret Water Board which consisted of the counties of Perth and Clackmannan. Since 1946 they had been considering the enlargement of an existing arrangement at Loch Turret which dated from 1872 and supplied Crieff. Loch Turret is seven miles north-west of Crieff in a natural valley at the foothills of the Grampians. It was agreed that Grangemouth should become a senior partner in this concern and on 11 December 1958 the Secretary of State for Scotland signed the necessary Water Order. The civil engineers for what was one of Scotland’s largest projects were Babtie, Shaw and Morton of Glasgow. The area of the loch was to be increased threefold and the water level raised 40-50ft, giving a storage capacity of 4000 million gallons. The estimated available supply from the loch was 18 million gallons per day and the estimated cost of the entire scheme was £6 million.

The laying of pipes from Grangemouth to Loch Turret began in 1959. As the supply to Grangemouth dropped 1,000ft in some 40 miles, break-pressure tanks were installed at various points en route. Each of the partners in the scheme required the water urgently, but this was a period of national credit squeeze and so the government’s Treasurer fixed a ceiling on the annual expenditure, which extended the implementation period.

It was for this reason that the pipelines were constructed first and in September 1961 unfiltered water from Loch Turret was available in Grangemouth. Wight Construction Ltd, Grangemouth, laid 30 miles of the trunk water main at the rate of more than a mile per month, often in difficult terrain and adverse weather conditions. This was the first occasion in Scotland when 36-in diameter pre-stressed concrete pipes had been used for this class of work.

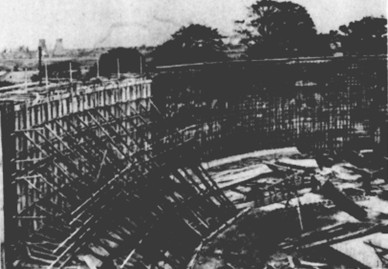

Tenders for the construction of the Turret dam were invited in February 1961. The works comprised an earthwork embankment about 70ft high and 1,100ft long, containing approximately 175,000 cubic yards of material, with mass concrete cut-off, a reinforced concrete core wall, outlet culvert, intake tower, overflow channel, service-road, and ancillary work. The conventional spill weir and channel were to have an energy dissipater and gauge basin at the foot of the dam.

By this date concrete cores had replaced the earlier ones of puddle clay in the design of dams for reservoirs and the use of grouts and sealants injected into the rock secured sound foundations without having to cut deep into the underlying strata. The contract, worth £650,000, was awarded to Lehane, Mackenzie & Shand Ltd of Matlock, Derbyshire, in August. It was 1963 before the contract for the construction of a 1½ million gallon reinforced concrete storage tank and the erection of a 5 million gallons per day temporary water treatment plant was issued. The Loch Turret Water Board decided to test a new system to purify the water which had been developed in France. This used ozonisation to sterilise the water and remove discolouration from the peaty matter. It was very successful and as it cost substantially less than the conventional filtration methods, which used chemical treatment followed by sand filtration, it was adopted for the permanent plant. Construction of the permanent plant began early in 1964 using electricity derived from the turbines at the damhead to produce the ozone. The new plant cost about £525,000, compared with an estimated £970,000 for installing the conventional method. Operating costs were also much less as the sand did not need to be taken out periodically and cleaned. It and the micro-filtration plant were fitted by Glenfield & Kennedy, engineers of Kilmarnock.

The whole plant and ancillary works were completed in 1967, and by then a second stage had been developed to increase supplies by a further 4 million gallons a day. As completed in September 1967 it supplied 18 million gallons of water a day – eight million for the southern half of Perthshire (from the outskirts of Perth city in the east to Aberfoyle in the west) and all of Clackmannanshire; and 10 million for industrial use at Grangemouth. The surplus electricity produced was exported to the North of Scotland Hydro-electric Board grid bringing in about £15,000 a year.

Sites and Monuments Record

| Millhall Reservoir | SMR 1885 | NS 9451 7851 |

| Upper Millhall tanks | SMR 2344 | NS 9451 7851 |

| Salmon Inn Service Reservoir | SMR 2246 | NS 9245 78877 |

| Buckieburn Reservoir | SMR 1942 | NS 7409 8544 |

Bibliography

| Gillespie, R. | 1879 | Round about Falkirk., p.226 |

| Porteous, R | 1994 | Grangemouth’s Modern History, 2nd ed. |