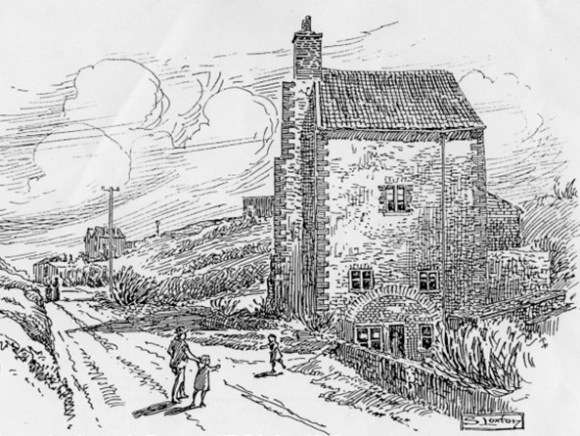

A Fire Engine House at Kinningars Park, Bo’ness

The Building

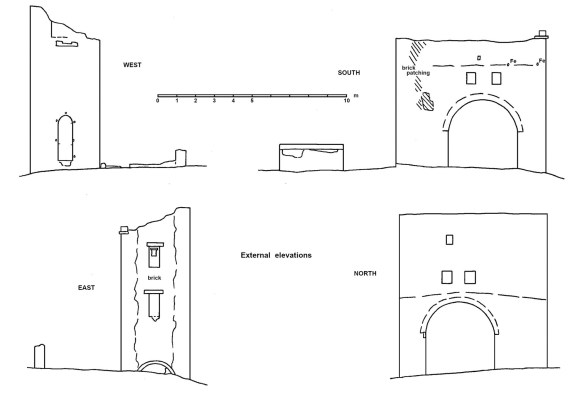

In Kinningars Park at Bridgeness (NT 0139 8129) stands a lectern style doocot which belonged to Grange House, the property of the Cadell family. The doocot, and the Park, were gifted to Falkirk Council in the 1970s. The 9m tall doocot is built of random sandstone rubble and patched with brick. It formerly possessed crow-steps, but only the lowest block now remains at the foot of the east skew. The upper storey of the building still possesses some 415 brick boxes. The building is now roofless and partially ruinous; but being part of Bo’ness it is no ordinary doocot.

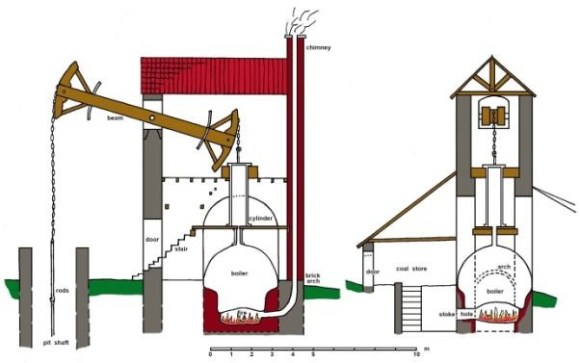

This doocot started life as an engine house in the mid-18th century. The structure is pierced by large round archways on the ground floor and a tall round-arched door in its west end, reflecting the fact that it had been constructed to house a pumping engine (now gone) for the nearby mine shaft. Indeed, close inspection provides enough detail to show how this building functioned.

The main building is rectangular in plan and is unusually narrow; it measures 7.9m west/east by 3.7m north/south. The north and south walls are 0.9m thick, the west wall 0.85m, and the east wall, the only one made of brick, is 0.35m. These widths reflect their functions. The west wall supported the heavy beam of the steam engine; the east contained the chimney and did not require structural strength; whilst the two long walls took the weight of the cylinder as well as buttressing the west wall.

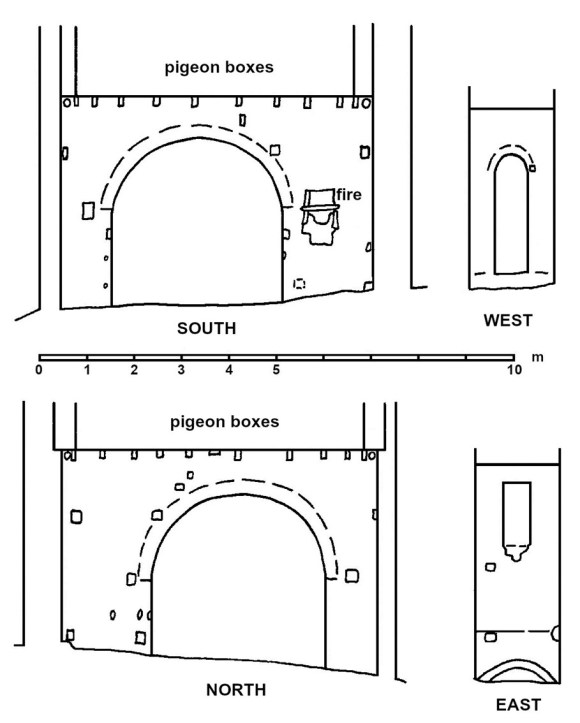

These last walls must extend down into a basement level which held the boiler in between them, and the furnace room to the south for stoking the boiler. The two large opposing arches, 3.7m broad, would have made the walls too weak if they had been of normal width. The requirement for a basement may explain the location of the building on the break of the natural hill slope.

So why were there two large arches? The two arches allowed a ‘haystack’ boiler to be fitted directly below the cylinder, with its shoulders projecting outside. They thus clasped the upper portion of the boiler and held it in their grip. This arrangement kept the width of the engine house down and negated the need for long, very heavy-section timbers to support the engine. The boiler could not be left open to the Scottish weather and so lean-to buildings on the outer sides of the arches sheltered it. That on the south had stone walls with a doorway near the south-east corner. It measured 7.9m by 4.5m externally and the raggle for its roof can still be seen on the south elevation of the main block along with iron fixing rods. It was still roofed at the time of the 1856 Ordnance Survey map. The northern extension was more flimsy and, as there was no need for an underground chamber there, would not have extended far out from the main block. It was probably a wooden structure.

The measured drawings of the external and internal elevations of the building show the positions of joist holes, iron fixtures, offsets and blocked up windows – all of which relate to the story of the building.

The east wall of the main block appears to have been largely rebuilt in the early 19th century reusing bricks from the earlier chimney which were there for their refractory quality – sandstone disintegrates with high temperatures over a period of time. At ground level the chimney was set on a stone foundation and a low arch was used at this point to make the replacement of heat-damaged material easier. Such arches are often found in the back walls of fireplaces from the 16th century onwards and examples can be seen at Kinneil House and Torwood Castle. The inner north, south and west walls of the chimney have been removed but their stone foundation can still be seen.

At a height of around 4.5m above the ground level both the north and south walls of the main block have scarcements (i.e. large offsets) for a wooden floor level. This coincides with the bases of the two rectangular slots above each of the large arches (now filled in with stone). These beam holes would have carried the substantial timbers necessary to support the cylinder of the steam engine and are set approximately 0.75m apart. Allowing for packing of the beams in these slots this is compatible with the suggested cylinder of 32 inches referred to below.

Large joist holes on the internal walls at a height of 1.7m above ground level (level with the springing of the large arches) would have supported a second wooden floor, which probably coincided with the bottom of the cylinder. Both of these floors were reached by a wooden staircase as evidenced by small sockets holes in the north wall. It was entered from the tall round-arched doorway in the west wall. This doorway is unusually tall in order to accommodate the rise in the steps. It is also noticeable that its outer sill is indented. At first sight this appears to be accidental damage, but running across the entire breadth of the doorway it is more likely that it incorporated one of the steps. The doorway passage was lined with timber as evidenced by lugs, but these may be of a later date.

A third floor probably existed above the floors mentioned to give access to that part of the beam that lay inside the building; this typically taking the form of a gallery in a beam chamber. Physical evidence for this floor is now hidden behind the later bird boxes but its former existence can also be deduced by the disposition of the intermediary windows in the east gable (see below).

That the west wall of the main block was the ‘bob wall’ for the beam engine is clear from its position midway between the pit shaft and the centre of the arched apertures. It supported the pivot axle of the beam or ‘bob.’

Where the beam extended through the end wall of the house there was a large opening near the top. Only the northern side of this still remains as the southern half was removed during the conversion of the building into a doocot. As this would have been central to the building the width of the aperture can be calculated as 1.5m. This is wide enough to allow for two small outdoor platforms on either side of the beam to give access from the beam chamber to each side of the beam for repair and maintenance operations. The outer end of the beam would have been positioned over the centre of the pit shaft and connected by a series of chains and rods to a large pumping mechanism. Each stroke of the engine/beam would have lifted a huge quantity of water from the bottom of the pit. This would have been discharged into a lined channel and fed downhill into the nearby stream. The stream is marked on the 1856 Ordnance Survey map running in a north-easterly direction to the Forth, passing alongside the eastern garden wall of Grange House. In the 18th century the coastline would have been just to the north of Bridgeness Road (A904).

The inner end of the beam was driven by a vertical connecting rod using power from the vertical piston of the cylinder. This configuration, with the engine directly driving a pump, was first used by Thomas Newcomen around 1705 to remove water from mines in Cornwall. The boiler for the steam engine at Kinningars was placed directly below the cylinder and would have been stoked from a chamber below the south lean-to structure. The ground floor of this extension would have been used to store the coal.

In the brick east wall of the main block are two window voids with stone lintels. The upper one was been partially filled in and a smaller window inserted. Behind the blocking are some of the nesting boxes for the birds, showing that the windows belong to a period before the conversion of the building into a doocot. However, they could not have been contemporary with the use of the building as an engine house as this was then part of the chimney. It would therefore seem that it may have been converted into a dwelling utilising the existing floors between the times that it was used as an engine house and then as a doocot. The inner chimney wall would have been removed to create more internal space and a new flue inserted in the south wall to the west of the arch for a smaller fireplace there.

History

In 1770 the Grange Colliery appears to have lain derelict for several years. A valuation was made of the works by John Kirk in December 1770. He was overseer of Wemyss and was appointed by William Belchier of Grange to examine and inspect the Grange Colliery on behalf of the landlord, and prospective tenant, John Beaumont of Newcastle on Tyne. He reported that the “fire Engine” had stood for years, the woodwork was very much decayed, the boiler much rusted and consumed, and ropes not fit for use after lying in the engine left for several years. This was the steam engine at the Miller Pit located between Drum and Kinglass. It appears that the water in the deeper Main Coal seam was lifted by the fire engine pump at the Miller’s Pit to the Coldwell Level where it was discharged on the face of the slope above Bridgeness.

The Grange records show that by the 28 July 1777 it had been resolved to sink a pit to the Smithy Coal as this was thought to be a good seam to mix with the Main Coal for the London Market. The Smithy Coal was to be won by erecting a small fire engine in the trough of the metal near the windmill at Bridgeness and in order to do this, an engine with a 32ins cylinder was to be purchased from Sir Archibald Hope with 17 fathoms of 12ins spigot and faucet pipes at £20 per ton bored and £10 a ton un-bored work. It was also resolved to drive a day level from high water mark to the place pitched upon for the engine pit in order to drain the coalfield to the south of the new engine. This is presumably connected with a contract awarded to Robert Morris in March 1777 to take the stair out of the Coneygair Pit and sink it circularly at 7ft diameter from the Main to the Smithy Coal. The pit at the new engine became known as the North Engine Pit, although latterly it was often referred to as the Doocot Pit. It was then close to the junction of the coast road and the road that ascended the hill towards Muirhouses – a little to the south-east of the windmill erected in 1750 (now known as Bridgeness Tower). On 28 Sep 1778 it was reported that the Nether Engine Pit had been sunk 3 fathoms below the Main Coal and had struck a feeder of water too strong to be drawn by a horse gin. Sinking had to be stopped until seven pipes were returned from Ayr to enable the engine to pump the water. On 17 November mention is made that the Company had built a fire engine for winning the Smithy Coal and made some progress in sinking the pits at considerable expense.

There was another very old pit called the “Cuningair Coal Sink” or “Old Mill Sink” in the south-east corner of the park. It was a square shaft and was said to be 14 fathom to the Smithy Coal and to have been “drooned wi’ the drouth”. The story, related by H.M. Cadell, was that it was drained by a pump worked by a water wheel from some vanished burn, and that there was a very dry season where the stream failed and the pump stopped and so the pit flooded. The pit is mentioned in an old feu charter about 1720 but was not worked in historic times. It was not uncommon for streams and springs in such areas to dry up as a result of the changes wrought to the drainage as a result of the coal mining activities. There is a dry valley running down the face of the hill from the north-west corner of the modern cemetery on Carriden Brae which probably held the lost stream.

The life of the Newcomen engine at the Doocot Pit was relatively short. In 1790 it was moved to No 3 Pit at a cost of £185 and it was resolved to stop the South Engine (at Miller’s Pit), thus ceasing operations to the south at Drum and Kinglass for the time being.

There is no record of the old engine house at the Doocot Pit being converted into a dwelling, but the windows in the east gable and the hearth in the south-west corner indicate that this was the case and may go some way to explaining why the south lean-to was still roofed in 1856. The wood panelling in the entrance passage may also belong to this period. Despite its apparently cramped space, it would have made quite a comfortable collier’s house for that period at a time when accommodation in the district was scarce.

James John Cadell moved from the old Grange House in Grange Terrace to a more convenient set of buildings adjacent to Kinningars Park in 1803 and this too became known as Grange House. It was probably at this time that the old Newcomen engine house was made into a doocot. This entailed reducing the height of the building, and particularly of the south wall. A monopitched roof was inserted with crow-stepped skews to either side. This faced south so that the birds could benefit from the warmth of the sun. A narrow sandstone eaves course capped the south wall and carried the roof beyond the wall. The pigeon boxes lined the walls of the upper chambers – leaving the middle floor in position. They are made with brick uprights and horizontal sandstone slabs. The boxes against the south and north walls rested on the scarcements, but lintels had to be inserted to support those on the end walls. The windows in the east gable were blocked up.

Between the 1895 and the 1914 Ordnance Survey maps the roof of the south lean-to was lost. In 1911 the pit next to the doocot was used for a short time as a source of water for the local population during a particularly bad drought. By then the Cadell family had moved to yet a newer Grange House on the Bonnytoun estate above Linlithgow and presumably the doocot was abandoned. It and the park were donated to Falkirk Council. In 1997 the wooden lintels supporting the nesting boxes on the west and east sides were badly damaged by fire caused by vandals and the Parks Dept replaced them with concrete beams.

Newcomen Engine Houses in Scotland

Perhaps the oldest engine house to survive in Scotland is that at Auchenharvie near Saltcoats. It is said to have been built in 1719 to hold a Newcomen atmospheric steam engine to pump water out of Auchenharvie No. 2 coal pit. It is believed to have been the second Newcomen steam engine in Scotland with a cylinder measuring 18 inches in diameter. An early photograph from around 1910 shows two beam holes in the west wall for supporting the cylinder. As the building measured 5.0m by 5.4m internally (with walls c0.85m thick) it was not necessary to incorporate lateral arches.

The year after the erection of the engine at Auchenharvie one was installed at Elphinstone (modern Dunmore) near Airth. Unfortunately nothing is known of the building which housed it. There is then a gap in the records and in 1760 the empty tower house at Skaithmuir was used by Thomas Dundas to accommodate a Newcomen steam engine (NSA) for the Quarrole Pit and a shaft was placed just 2m to the south of it. There were around twenty engines operating in Scotland at the time (see Duckham 1970, 83). Adam Smith and Mr Wright were in charge of the engine at Skaithmuir. Carron Company took over the lease of the colliery in August 1760 to feed its blast furnaces. Adam Smith was retained and helped to erect another steam engine at the developing adjacent Kinnaird Colliery.

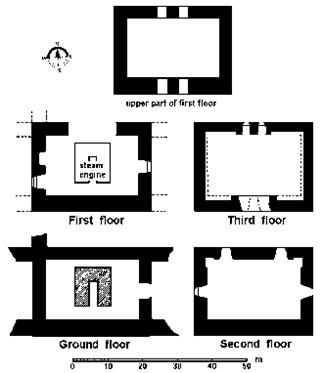

The other end of the beam extended out from the building and hovered above the shaft previously mentioned. A chain of rods connected this end of the beam to the shaft and the upwards and downwards motion of the beam created the necessary vacuum to raise water out of the pit. Two segmentally-arched openings, 0.81m wide, immediately above the level of the crown voussoirs of the large arch provided sockets for large timber beams which supported the cylinder and were matched by a similar pair in the south wall. The floor levels were changed to provide access to the machinery for its operation and maintenance.

At Skaithmuir Tower the most noticeable alteration was the insertion of a large arched opening, 4.4m wide, in the centre of the north wall. The stone vaulting on the first floor was removed and a central rubble platform was placed in the former basement to provide the seating for a furnace and boiler. The large entrance arch made access easier as well as providing a suitable updraft. Presumably coal would be stored to either side of the furnace. Above this would have been the cylinder, with the piston rod extending upwards from it, attached by a chain to one end of a large beam. The centre of the beam rested on pivots housed in the enlarged window openings in the south wall at third floor level.

The tower measured 10.5m from east to west by 7.7m, over walls averaging 1.0m in thickness and so was large enough to comfortably house the boiler without the need for the large external arch. However, this was an old building with small openings and it would have been impossible to have got the equipment inside without some modification to the fabric. There is a hint that even in new-build engine houses the provision of such an arch would allow for the repair or replacement of the massive machinery at intervals. These were largely untested designs and the efficiency of the emerging technology rapidly increased.

The engine house at Skaithmuir is actually depicted on Roy’s map, whereas that at Bridgeness is not – additional evidence of the latter’s late date.

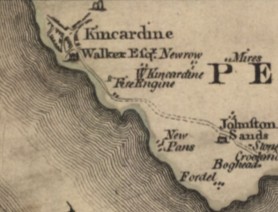

Another local building with the beam holes and central arch, of lesser dimensions than those so far dealt with, occurred at Kincardine on the other side of the Forth (at NS 934 869). It was built as an engine house for the colliery there and had a pit shaft just outside of it. The “Fire Engine” is shown on Ainslie’s map of 1775 and is presumably that fitted for Cochrane in 1773 (see the online ‘Early Engine Database’ by John Kanefsky). Ground floor archways of this nature are a common feature of the engine houses in Cornwall for the tin mining industry.

This building was converted into a jail in 1828 (Maclaren 1949, 64). Unfortunately the structure has been completely eradicated and the only record of it is the photograph shown here. It is not therefore known if there was a corresponding arch on the opposite side.

Bibliography

| Duckham, B.F. | 1970 | A History of the Scottish Coal Industry, Volume 1L 1700-1815. |

| Maclaren, W.B. | 1949 | ‘Skaithmuir,’ Proc Falkirk Archaeological & Natural History Soc, 4, 57-65. |

| NSA | New Statistical Account of Airth. | |

| Watters, B. | 2010 | Carron; where Iron runs like Water |

| The Cadell archive in the National Library of Scotland. |

Sites and Monuments Record

| Kinningars Doocot | SMR 33 | NT 0139 8129 |