Until the nineteenth century the only contact that most of the people in the Falkirk district had with electricity was in the form of lightning. The dreadful effects of this electric fluid were the kind of tales that scared the children and installed the fear of God, with livestock, people and buildings being struck low.

Scientists began exploring the natural world and experimentation inevitably led to a better understanding of the phenomenon and to the belief that it could be harnessed to the advantage of humanity. The first inklings of the practical applications of electricity came from reports in the 1840s of the use of the electric telegraph on the Continent and its rapid spread throughout the world. This was a truly wonderful achievement and many were incredulous that it was possible to transmit messages so far, so rapidly, and so accurately. In March 1849 John Adam, a Fellow of the Royal Society, came to Falkirk and gave a lecture on “Electric Light” which he and others prophesied would bring about a huge revolution in working and living conditions, changing culture and society for the better. Already, the coming of the railways had unified the country and brought about the need for a standard time zone. By 1852 it had become possible to regulate all of the public clocks throughout the kingdom in accordance with Greenwich or railway time by means of the electric telegraph. Precisely at noon the signal indicating Greenwich Time was transmitted. In 1861 an electric wire was suspended in mid-air between the Royal Observatory on Calton Hill in Edinburgh and the Castle so that a time signal could be sent and the one o’clock gun fired.

Unsurprisingly, it was commerce that drove the introduction of electricity into society. The advantages of fast communication are obvious and in 1856 Falkirk was joined to the outside world by telegraph. The railway network allowed for the rapid erection of the necessary poles to carry the wires and the first telegraphic office was at Grahamston Station. However, it was 1864 before the office of the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company was opened in Wilson’s Buildings on the High Street for the transaction of business in the town centre. And as with all such innovations this expansion led to a reduction in price and an increased uptake and then regulation. That regulation came in 1870 with the nationalisation of the system in Britain under the control of the Post Office.

Not only could electricity be utilised to increase productivity but it could also enhance safety. The explosives used in mines could be detonated from a safe distance by an electric current which was far more reliable than the previous methods and was introduced in the 1850s. It was also turned to good advantage in the railways for co-ordinating the passage of trains, especially along single tracks. These used simple signals provided by bells and the same principle of communication was introduced into offices and shops. The first office block in Falkirk to be completely fitted with electric bells was that of the Inland Revenue in Bank Street in 1879, fitted by Mr Strang of Bainsford who was described as an “electric bell hanger.” By 1860 it was obvious that the electric revolution was on its way and Priestley’s early electric engine which he had put together in Birmingham was placed in the British museum to chart its progress. In the 1860s the lighthouses around Britain’s coast adopted the use of magneto-electric machines to provide a brighter, more penetrating light.

In 1863 a Mr Barker held an exhibition at the Corn Exchange in Falkirk’s Newmarket Street. In it he provided a panorama of David Livingstone’s celebrated explorations which opened up the geography of Africa. This was accompanied by the exploration of a new frontier in the shape of practical experiments in galvanic electricity. Most of the early uses of electricity were an extension of the telegraph and relied on electricity produced by chemical batteries but the work of men like Faraday and Priestley made it possible to safely generate electricity in larger amounts using magnets and to convert it into a source of power to do work. Over the following decades there was an explosion in the number of patents for electrically driven appliances. Even an electric hair drier and curler was put forward in the 1860s! On a more macabre note, slaughterhouses and criminal executioners in the 1870s harnessed the clean quickness of the electric current.

Still, in Falkirk, electricity was seen more as a curiosity and an amusement. At the Falkirk half-yearly Feeing Fair in November 1872, where farm servants were hired, the chief attractions were cheap johns, merry-go-rounds, photographic booths, “sweetie” stands, exhibitors of fat persons, muscular indicators, jugglers, fiddlers, ballad-singers, preachers, and electric batteries. The latter used to deliver shocks. Electric bells, clocks and telephones were in circulation but in a provincial town such as Falkirk they were not that familiar. In January 1878 the Falkirk Herald hosted a display in its office on the High Street of the art of speaking by electricity and so the first telephone in the town made its appearance.

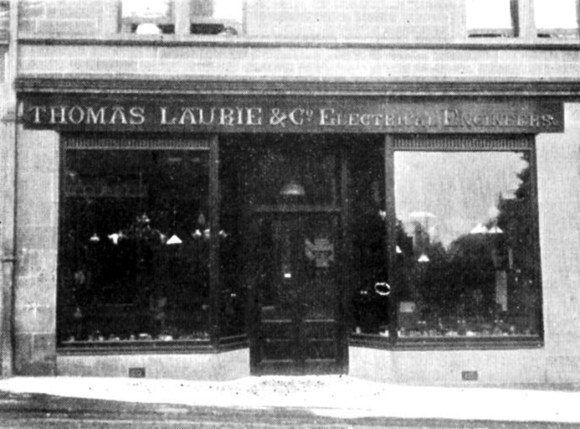

In 1881 the firm of Thomas Laurie & Co was established in Camelon. The range of work that it could undertake is illustrated in this advert:

“THOMAS LAURIE, ELECTRICIAN, CAMELON, ELECTRIC BELLS, TELEPHONES, TELEGRAPH INSTRUMENTS, COLLIERY and MINING SIGNALS, BURGLAR, FROST ALARMS, SPEAKING TUBES, & Manufactured, Erected, and Maintained on Reasonable Terms, References Buildings already Fitted.” (Falkirk Herald 6 May 1882, 1).

It was the leading electrical engineering business in the Falkirk district for many decades to come and proved its worth by installing many systems for industry and private usage.

At this time, the brightest future (forgive the pun) for electricity was still seen as the provision of lighting. The equipment and systems developed by leaps and bounds, with practical input from men like Edison to make it affordable. In 1878 three electric street lamps had been turned on in Pall Mall and Waterloo Place in London, demonstrating its efficacy. The following year a select Parliamentary Committee was appointed to enquire into the matter and in 1882 the Electric Lighting Act was passed. Whilst the title suggested that this was for street lighting, it actually covered the production and distribution of all electrical power, giving the leading role to the local authorities responsible for governing burghs and urban settlements. Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen were amongst the first in Scotland to take up the challenge. Unsurprisingly, Falkirk lagged well behind. Part of the reason for that was that Falkirk Town Council owned and ran the local gas works and there was a concern that a switch to electric lighting might diminish the demand for that product.

The first electric lighting system in the Falkirk District was, naturally, installed for one of the larger commercial concerns. At the back end of 1883 the Caledonian Railway Company commissioned Norman & Sons, engineers and electricians, Glasgow, to place twelve lamps in Grangemouth Docks to facilitate the loading and unloading of ships outwith daylight hours. Delays in turning ships around were costly. There were already gas lamps there, but the illumination was poor and not only would the new system provide more light, it would enhance safety. Norman & Sons had already installed electric lighting at the Central Station in Glasgow, and the docks at Barrow-on-Furness. The twelve arc-lights at Grangemouth Docks were officially turned on at 6.30pm on 11 January 1884 by the town’s Chief Magistrate (i.e. provost), Hugh Macpherson. It was the first port in Scotland to be so lit. The carbon arc-lamps were of a new design, called the “Crab”. They were surmounted by iron shades, which served to shed the rays of light downwards, and to secure the light against being blown out by high winds. Power was supplied by a Well’s Patent Compound 50 horse-power engine supplied by Lamberton & Co of Coatbridge, using steam from the large boilers which supplied the other machinery round the docks. This drove two Burgen patent electric machines.

There was an unfortunate setback for the lighting at Grangemouth Docks when the work of Norman & Son was found to be deficient and had to be redone. They were again lit in May 1885 when the following report was printed:

“The docks here were successfully illuminated on Saturday night by the electric light. There are twelve arc lamps of great power suspended on 50ft posts throughout the dock. The lamps are of the Brush pattern, and fitted with dioptric or diffusion glass, which has a remarkably pleasing effect, preventing the glare and shadows that are found so objectionable with ordinary glass globes. The dynamos used are those of the British Corporation, with improved laminated armature. The engine, boiler, and gearing were specially built for the installation by Mr John Bennie, Star Engineering Works, Glasgow, and the work has now been constructed under the superintendence of Mr Andrew Dunn, telegraph engineer of the Caledonian Railway Company” (Falkirk Herald 27 May 1885, 3).

It was not the only lighting scheme at the Docks. From 1885 onwards most of the new ships built at Grangemouth were fitted with complete systems of electric lighting and some electric appliances. All of Carron Company’s new passenger steamers were lighted throughout with electricity.

Just one year after the renewal of the electric lighting at Grangemouth Docks another important institution in the district introduced electric lighting. This was the nationally-important private boarding school at Blair Lodge at Brightons. The school’s headmaster and owner, Mr Cooke-Gray was keen on providing the right environment for his students and the better quality light without the fumes of gas was seen as important for this. At first the main buildings were provided with the lighting and over the years this was extended. In September 1886 the valuation of the property was increased from £225 to £285 as a consequence. In 1892 a new church and a new hospital at the school were added to the system, as were the house of the school’s vice-principal, and Blairbank, the residence of H A Salvesen. The church had a large pipe organ blown by an electric motor, and the sanatorium, which was some distance from the main buildings of Blairlodge, was connected by telephone. The following year the gateway and the long avenue leading from the public road were lighted by incandescent lamps. The lamps were enclosed in glass globes mounted on light iron standards. The electricity was tapped from the mains which conveyed the current to the hospital. All of this work was carried out by Thomas Laurie & Co, Falkirk. It was thus the first private institution in Scotland to introduce the electric light on a large scale, there being between 800 and 900 lights illuminating the school, the outlying masters’ houses, the hospital and the avenues.

The cheapest source of power for electric lighting came from water turbines and it was natural for it to be explored. It was not always suitable. In 1886 John Collins of the Stoneywood and Herbertshire Paper Mills in Denny investigated the possibilities of using the falls at the Hermitage on the River Carron for the works but found it impracticable. A few years later, in 1891, James McKillop wanted to introduce electric power into his home at Polmont Park. The cheap power from the Polmont Burn in the glen naturally suggested itself for the electric light, but after careful and rigid examination, it was found that the flow was insufficient to generate the 7 horse-power required. Steam power was too expensive. Some of his neighbours manufactured their own gas but this was time consuming and also expensive. In the end he bought a Sun gas machine which consumed gasoline and was capable of supplying 120 lights.

In 1893 the Hospital Committee of Falkirk Town Council decided to look into the possibility of lighting the fever hospital with electricity. It hoped that the power to drive the necessary dynamo might be obtained from the engine at the Burgh Stables in High Station Road used to pump water to the hospital. William Neilson, the burgh surveyor, was asked to report, which he did in March that year:

“As instructed by the Hospital Committee, I have made enquiry as to the lighting of the burgh hospital with electric light, the dynamos to be driven by the hydraulic engine placed at the burgh stables, which is used for pumping the water to the hospital. I have found from investigation that this engine is not steady enough in its action, neither has it speed or strength for electric lighting. After finding that this engine was practically of no use for this purpose, I turned my attention to the water discharging into Little Denny reservoir from Faughlin Burn reservoir. John Ritchie, engineer, Edinburgh, and an electric engineer, a representative of Cox Walker’s North Eastern Electric Works, Darlington, called on me, and I drove them out to examine the water being discharged into Little Denny reservoir from the Faughlin Burn pipes. I gave them the levels of the respective reservoirs and the quantity of water daily consumed by the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trustees, and they are of opinion, that by attaching a turbine wheel to the end of this pipe that it would be equal to at least 200 horse power for the purpose of electric lighting. They also state that another turbine could be erected as the water leaves Little Denny reservoir and before it enters the filters, which would be equal to about another 30 horse power. Of course this was a rough estimate done on the ground without having the exact pressures tested as to the horse power. From the conversation I had with these engineers, I am of opinion that the whole of the public lighting in this burgh, including public buildings, with an electric light by a driving power from this source, could be done at a cost of little over £500 per annum, this sum including interest on capital, maintenance, and all expense, and leaving over 100 horse power available for private lighting. During the year ending 15th May 1892 the burgh paid for gas, wages to lamp-lighters, and other repairs, a sum of £1081 12s. This method of lighting, of course, could only be done with the sanction of the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trustees. Those engineers who visited the ground with me are prepared to submit an offer for this lighting of the town.”

Bo’ness Town Council was also investigating the possibility of hydro-electric power and in August 1893 its Commissioners visited Tod’s Mill on the River Avon to view the possibilities there.

Blairlodge School was in the forefront of teaching electricity to its pupils and in 1894 it was noted that a great advantage to science teaching there was obtained from having dynamos and other electric light machinery on the spot. These were directly connected with the workshop, enabling a boy to obtain a thorough knowledge of the practical applications of electricity. However, Falkirk Science & Art School in Park Street had introduced classes for steam, mechanics, electricity, and magnetism, in 1884.

The 1882 Electric Lighting Act had acted as a brake to the introduction of electricity to many towns because it gave too much control to local government authorities. Private companies applying for Provisional Orders from the Board of Trade to install a central power station in an urban area could have it blocked by the local council. A further Act of 1888 attempted to alleviate this problem. From then on any private company could apply for a Provisional Order and if they were opposed by the local authority that authority had to come up with an alternative supply within a limited period of around two years or else the Order would be granted. This was a game-changer, but with the objection, time after time, of Falkirk Town Council most firms were put off.

| DATE | TOWN | PRIVATE COMPANY | REACTION |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 1889 | Falkirk | Scottish House to House Electricity Co Ltd | Council Objected |

| July 1893 | Falkirk | Caledonian Electric Supply Company (Ltd) | Council Objected |

| July 1897 | Falkirk | Electric Lighting and Power Co, London | Council Objected |

| July 1898 | Falkirk | Bergtheil & Young, London | Council Objected |

| July 1898 | Denny | An electric light company | Council Objected |

| June 1899 | Falkirk | Electric Supply Stores, Glebe St, Falkirk | Council Objected |

| October 1899 | Falkirk | Edmonstone’s Electricity Corporation (Ltd) | Discussion – Objected |

| July 1900 | Grangemouth | North British Electricity Supply Co. | Council Objected |

| August 1900 | Bo’ness | National Electric Construction Co Ltd, London | Council Agreed |

Meanwhile, electricity remained somewhat of a novelty in the area. At a soiree in the Columbian Stove Works Hall in Bonnybridge in March 1855, several small Swan incandescent lamps were suspended across the room from a wire and “added brilliancy to beauty” to the occasion (Falkirk Herald 7 March 1885, 5). And at the Falkirk Parish Church Bazaar in the town hall in Newmarket Street in March 1891, telephones in working order and other electrical appliances, were supplied by Thomas Laurie & Co and proved a huge attraction (Falkirk Herald 21 March 1891, 6). These must have been battery operated.

Private individuals took up the baton of installing electric lighting. In May 1893 the Falkirk Herald reported that:

“An interesting event, and one which may be regarded as the inauguration of electric lighting in Falkirk, took place on Wednesday evening, when the light was introduced into the residence of Mr. T. Blackadder, of the firm of Messrs Blackadder Bros., of Garrison Foundry and Engine Works The house is situated in Park Entry, (Park Terrace) near the works…”

This being such an unusual occurrence it was described in detail:

“Messrs Blackadder Bros. have made the dynamo and plant required for the Installation, and have also fitted in the wires, &c for the distribution of the electric current throughout Garrison Cottage.

Simplicity being one of the chief points aimed at in the design and with a view of introducing storage cells or accumulators for the storage of electrical energy during the time that power can be obtained most easily – namely, during the daytime – the current used is at a very low tension of 50 volts. As presently fitted, the current is carried direct from the dynamo, this, of course, necessitating the running of the main engine in Messrs Blackadder’s Works from which the motive power from the dynamo is taken by belting, while the light is on, but after accumulators are introduced electric energy will be stored during the day when the engine is doing its usual work, the stored energy being used as required at any subsequent time.

The dynamo is a well finished looking machine, having a built up armature, about 400 discs of thin charcoal iron being used in its construction. The armature is wound with 48 coils of insulated wire, the extremities of these coils being connected to a commutator having 48 sections, from which the current is taken by means of brass wire gauze brushes. The field magnets of this machine are of a very soft cast iron, and are excited, or magnetised, by a portion of the current produced, being carried round them through 4 coils of insulated wire having an aggregate length of fully two miles.

With the armature revolving at the rate of 1600 revolutions per minute sufficient current is generated to light about 60 incandescent lamps. Copper wires of a suitable section carry the current from the dynamo to Garrison Cottage, which is then distributed to the lamps in the various rooms. On the parallel arrangement two heavy wires are run side-by-side, branch or shunt wires being taken off to feed the various lamps with current. All wires are run in wood channels with beaded covers, which can be easily removed to admit access to the wires. Switches are provided at the door of each room and on turning a key on entering the room the lamps are immediately incandescent the reversal of this key again puts the lamps out of the circuit, and the light is extinguished. At the trial on Wednesday evening the light was exceedingly steady, there being no shadows, and every detail in the rooms was clearly illuminated.

Edison-Swan incandescent lamps of 16 candle power each, at an E.M.F. of 50 volts, are used, two in each room being sufficient. These lamps, which really consist of a loop of specially prepared carbon, enclosed in a small glass globe, exhausted and hermetically sealed, give off a very small amount of heat, and as nothing is really burning the carbon only being incandescent, no fumes or gasses are given off, and the atmosphere is therefore left pure and untainted.” (Falkirk Herald 20 May 1893, 4).

Blackadder Brothers Garrison Foundry & Engine Works in MacFarlane Crescent not only installed the electrical wiring and fittings, they also manufactured the dynamo. This would suggest that they were experienced, not only in the wiring of installations but also the generating of electricity and the design of dynamos. It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that they had their own electrical department.

Another important step occurred in March 1895 when the private dwelling of Mr Cumming, a dentist, in Grahams Road was supplied with electric light from Springfield Sawmill. The wire was carried across Grahams Road at a height which would not interfere with the traffic. As the local newspaper noted:

“This is a precedent that may be largely taken advantage of; least, it is proof, as far as things have gone, that the Commissioners have no objection to a private firm supplying the electric light to private houses” (Falkirk Herald 9 March 1895, 4).

And the following year this was extended to Dr Pragnell’s premises.

| DATE | TELEPHONE | INSTALLER |

|---|---|---|

| 1892 | Stein & Co, Bonnybridge; offices to works | Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1892 | Blairlodge School; school to sanatorium | Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1893 | Burgh Buildings, Newmarket St – Lochgreen Hospital | Thomas Laurie & Co. |

Industry and commerce pressed on regardless.

| DATE | LOCATION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| 1880s | Underwood House | “Tangye” steam engine of 2 hp, with upright Boiler, electric dynamo and accumulators, incandescent lamps and fittings. |

| 1887 | Stoneywood & Herbertshire Paper Mills, Denny | Electric lighting throughout the works. |

| 1892 | Bonnybridge Brickworks | New office of Stein & Co fitted with electric light, bells and a telephone to the works byThomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1893 | Vicar St restaurant | Electric bells. |

| 1895 | Springfield Saw Mills | Electric incandescent lighting in the offices and arc lamps in the works; Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1895 | Larbert Foundry | Dobbie, Forbes, & Co had the entire works lit by electricity; Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1896 | Bo’ness Distillery | James Calder & Co Ltd re-opened the distillery with electric lighting throughout. |

| 1897 | Falkirk Iron Works, enamelling department | Lit by electricity; Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1898 | Westquarter Explosives Works | Nobel’s work lit with electricity and electric door bells. |

| 1898 | SCWS Soapworks, Grangemouth | entire buildings lighted by a special installation of electricity. |

| 1898 | Carrongrove Papermill | Installed electric light using the spare engine power it had. |

| 1899 | Carmuirs Foundry | New foundry lit entirely with electricity by Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1899 | Laurieston Iron Works | Complete installation of electric light in new foundry. Dynamo with a capacity of 500 8-candle incandescent lamps, driven by the main foundry engine. Thomas Laurie and Co, electrical engineers, included patent sliding lamp system. |

| 1899 | Gowanbank Iron Works | Install electric lighting in existing foundry. Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1899 | Dorrator Iron Works | Complete installation of electric light in new foundry. Thomas Laurie and Co. |

| 1899 | Herbertshire Brickworks | Arc and incandescent lamps. |

| 1900 | Grange Foundry | Electric light in foundry extension. Thomas Laurie & Co. |

| 1900 | Bonnyside Brick Works | Electric lighting, Thomas Laurie & Co. |

The advert of Thomas Laurie & Co had changed to reflect the work that it now did:

“ELECTRIC LIGHTING AND TRANSMISSION OF POWER, TELEPHONES, ELECTRIC MINING AND HOUSE BELLS, Lightning Conductors, Speaking Tubes, &c. Short Distance Telephones, £3 per Station. All Work Guaranteed. Established 12 years. THOMAS LAURIE & CO., ELECTRICAL ENGINEERS.” (Falkirk Herald 28 July 1894, 8).

The use of electric lighting in coal mines was now relatively standard and was a necessary safety measure to guard against the explosion of gas. John Watson of Earnock had pits throughout central Scotland, including in the Slamannan district. He was the first in Scotland, and the second in the United Kingdom, to introduce the electric light underground, and all his collieries soon had modern electrically-powered mechanical appliances. A fatal explosion in the Woodyett Pit, Denny, in 1893 led to the introduction there the following year of a new form of safety lamp. The new lamp was lit by means of electricity and if an attempt was made to open it the light went out. At the time, Woodyett was the only mine in the district where this particular lamp was in use, but in most of the other pits they had lamps which were provided with extinguishers if an effort was made to open them. The only chance left for miners to get a surreptitious smoke was to conceal matches about their persons (Falkirk Herald 2 June 1894, 6).

Another catastrophic explosion occurred underground at the Quarter Pit north of Denny in 1895 (see Martin 2013) and thirteen men died. The ensuing rescue operation, which turned out to be the recovery of the bodies, was lit by temporary electric lighting under the charge of a Glasgow firm of electrical engineers. This allowed the underground exploration to be done safely and expeditiously and the men spoke in high praise of the light. Towards the end of that year four miners were fined for carrying matches to the coal face of a nearby pit – Herbertshire No 2 – which also suffered from the presence of fire-damp. The fact that that pit had never had an explosion was put down to the use of electric lamps.

Iron foundries too started to introduce electric lighting as it provided a better working light and was safer and cheaper than gas if the entire works were fitted out. Dobbie, Forbes, and Co had its Larbert Foundry upgraded by Thomas Laurie & Co in 1895. This foundry was the first in the district in which electric lighting has been introduced. A large dynamo capable of supplying 400 incandescent lamps and a Robey steam engine were laid down especially for the purpose. The machinery was housed in a room lined with white enamelled brick, which also contained the switchboard and meters, from which all the main conductors branched to the various departments of the work. By a special distribution of the lamps in many of the places one incandescent lamp replaced four gas jets and in other portions two gas jets. The loading bank, formerly lit by oil lamps, was brilliantly illuminated by large arc lamps, facilitating the packing and loading of trucks in the dark weather. The offices and pattern-shops were also lighted throughout with incandescent lamps. The main arteries of the moulding shops and furnace were lighted by arc lamps, allowing the somewhat dangerous process of running the molten iron in bogie ladles with less risk of mishap. An ingenious arrangement, invented and patented by Thomas Laurie, was used in the moulding shops. By it, each moulder could traverse his lamp from end to end of his long and narrow working place or “row.” Overhead, and in line with the “row” a wire rope was run and from it each man’s lamp was suspended. It could slide the full length and light his work at any point. There was a flexible conductor to each lamp running the whole length, and to obviate the slack it was made to automatically fold up at the end as it was moved along. The lamp could also be raised or lowered by a little hook. Such was the success of the new lighting that by the end of 1896 there were two large engines and dynamos at the foundry with a capacity of about 900 lights to allow for future expansion.

1899 witnessed a large expansion in ironfounding capacity with the establishment of new works and the extension of others. Thomas Laurie & Co was busy at the new foundries at Laurieston, Carmuirs, Dorrator and Grange, as well as the older ones at Gowanbank and Falkirk. It was also commissioned to install lighting at the Bonnyside Brick Works. The aggregate capacity of all of this new plant was equal to 4500 8-candle incandescent lamps. Laurie’s patent sliding lamps proved popular and as well as being used in most of the local foundries the company received contracts to fit them elsewhere.

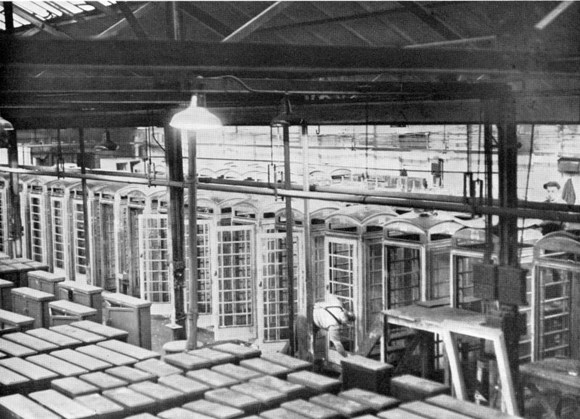

In August 1898 the Northern Iron Co arranged for them to be installed in its new warehouse in Belvedere Road in London. In November that year Fletcher, Russell & Co hired Thomas Laurie & Co to fit out its large new foundry in Warrington. And in 1900 Bennett’s Iron Foundry Co Ltd had Laurie’s install its patent lamps into its foundry in Manchester. Before long the foundries were making casings for engines and dynamos, electrical switchboxes, cabinets and other equipment; and from the 1920s the classic public telephone kiosks.

The Enamelling Shops at Falkirk Foundry were lit by electricity in 1896. The Enamelling Department employed a large number of women and questions were asked in Parliament about their working conditions. An inspection in 1897 showed that they were very favourable. The electric light did not have the fumes of the gas lighting and provided a better light. The shops were separate from the main foundry and were located to its west. On the west side of these buildings there was a gas-producing plant, with a holder capable of supplying gas to two large engines, and for driving the various machinery and the dynamo for electric lighting purposes, as also for driving the Blackman and other fans for ventilation.

The mobility and brilliance of electric lighting were not the only advantages. It was cleaner than gas and this meant that in a retail environment there would be less damage to shop stock. In November 1896 James Haddow & Co instructed Thomas Laurie & Co to light its aerated water works and shop on the corner of Vicar Street and Melville Street with electricity. Once again this was such a novel occurrence that it was fully reported:

“Electric Lighting.—Electricity as illuminant is gradually edging its way into our town and neighbourhood. Among the latest installations in the town is one erected in the large establishments of Messrs James Haddow & Co, Vicar Street and Melville Street. The dynamo, capable of supplying 100 incandescent lights, has been laid down in the engine-room of their works in Melville Street. Here one of Crossley’s 4 nominal horse-power gas engines is placed, which drives all their aerated water plant and machinery, in addition to the dynamo. A very handsome switchboard has also been placed here, with the usual instruments for measuring the current and switches controlling the various sections of the lights. In the works, warehouse, and offices incandescent lamps are fixed, while the cellars are fitted with moveable lamps, which can be carried about and light every corner effectively. From the switchboard overhead cables are led to their large grocery establishment in Vicar Street to another distributing switchboard. All the counters, and office and store here, are lighted by incandescent lamps, beautiful clusters with handsome brass fittings being suspended over the counters. In the two large windows facing Vicar Street and Melville Street are fitted the latest improvement in arc lamps, which, unlike the older form, only require new carbons about for every 150 hours’ lighting, the older form lasting only 10 to 20 hours – decidedly a very great advance. When all is turned on a very fine and effective appearance is given to the premises and is really an ideal illuminant. Unlike all other means of lighting, electricity is the only one devoid of any destructive propensities in the form of fumes or smoke, &c, and when goods exposed to these elements are liable to damage electric lighting should commend itself… The installation has been successfully carried out by Messrs Thomas Laurie & Co, electricians, Falkirk.

The following is a list of the lights and their positions throughout Mr Haddow’s premises:

Melville Street Works – private office, one 32 candle lamp; public office one 32 cl; wine and spirit warehouse two 50cl; beer bottling cellar three 32cl; wine cellar on 32cl; engine and dynamo room one 16cl; aerated water works six 32cl; syrup room one 16cl; sugar store one 16 cl; aerated water store one 16cl;

Vicar Street Shop – twelve 32cl over counters; office one 16cl; store one 16cl; windows two arc lamps.” (Falkirk Herald 26 December 1896, 4).

One evening in February 1898 a meeting of a number of gentlemen was held in Mrs Conochie’s Temperance Hotel in Falkirk to consider the practicability of introducing the electric light into business premises in that portion of the High Street extending from Roberts Wynd to the Herald Office. Most of the shopkeepers in that part of the street attended. Estimates were furnished by Thomas Laurie, and the matter was discussed in all its bearings. The estimates were considered reasonable (Falkirk Herald 26 February 1898, 4). The Falkirk Electric Lighting Association was formed for the purpose of procuring plant for lighting the shops of the associated firms, namely, Shields and Hutchison, ironmongers; William Forgie, chemist; David Kennedy, draper; John Callander, stationer; John Watson and Son, shoemakers; Mr Brown, Blue Bell Inn; and W.W. Hope, tailor. In August a contract was issued to Thomas Laurie & Co for that purpose with high expectations of being completed that October. The plant that the association contracted for was capable of giving 150 16-candle electric lamps without storage, but by the introduction of storage another 150 lights could be added. The lights had not been fully taken up, but it was expected there would be a demand for them by other shopkeepers. The dynamo was to be driven by a 15-horse power gas engine. David Kennedy was the president of the Association which deliberately avoided calling itself a “company” in order to avoid objections from the Town Council. In September HB Watson, the Association’s secretary, wrote to Falkirk Town Council applying for a gas main to its premises in Blue Bell Court to supply the engine. It caused quite a stir. The Gas Committee was willing to provide the gas to yet another consumer but much depended upon the full Council’s policy towards electric lighting in the burgh. It had seen the success of Glasgow Corporation which made a good profit by running its own plant, but it had no definite plans of its own. It was noted that if it was to construct an electric power station in the future it might have to compensate the Falkirk Central Lighting Association. As usual it resorted to delaying tactics.

The Association had been very canny in laying out its constitution and fully cooperated with the Council over the application, firmly laying down the fact that the generation of electricity was only at the Council’s “pleasure.” The Council felt confident that they could nip any expansion in the bud because it could prevent the Association opening up the roads and interfering with them. As part of its promotion the Association agreed to provide electric lighting to the Town Hall for the Town Mission bazaar that year and the Council agreed to a wire being led to it from Blue Bell Close which was to be left for future use, though it had to be turned off after the bazaar was over. The electric current to the association’s members was transmitted through overhead cables along the backcourts of the High Street to the various shops. At the beginning of December the light was turned on in the shops of David Kennedy, draper; Messrs John Watson and Son, shoemakers; Mr John Callander, stationer; Mr Forgie, chemist; and Messrs Shields and Hutchison, ironmongers; and in the Blue Bell Inn. Once again the Association was canny enough to invite Provost Weir to perform the official turning on of the light in the dynamo house in Blue Bell Court on 9 December 1898. He was enthusiastic about the new lighting and in a long speech suggested the way in which future development should go.

. “Although electric light had been a good deal used in other towns to light up shops, this was the first time it had been employed to any extent for such a purpose in Falkirk. He had no doubt that electricity would grow in favour amongst the shopkeepers, and that by and bye many others would be desirous of connecting themselves with the association. He thought it would be a good thing for the Corporation [ie Town Council] to seek powers to supply electric light to those who wished it. He did not see why they should have small corporations starting up here and there to supply this light. The Town Council ought to follow the example of other towns, and apply for a Provisional Order to supply this light themselves, in order to prevent others from supplying it. He had great pleasure in turning on the light.” (Falkirk Herald 10 December 1898, 5).

Its success was instant and within a week the Association requested permission to carry a cable across Cow Wynd to supply electricity to the shop of Mr Dillon. The Council was caught unprepared and the burgh surveyor was instructed to procure information from other towns as to the method of transmitting electricity from one portion of the town to any other, and any other information bearing on the subject. Permission was then granted on the express understanding that the cable was to be laid underground to the satisfaction of the burgh surveyor. At the end of the month the members of the Association noted that their midnight illuminations over the Christmas period had resulted in enhanced trade. Dillon and Sons enlarged premises opened at 147 High Street in March 1899 with electric lighting throughout.

Electric appliances were now popular enough for another shop supplying light fittings to open in Falkirk in May 1899. It was located in Glebe Street and presumably had its own dynamo. It also supplied dynamos and accumulating batteries to the public. The General Electric Supply Stores sold:

“the longest-distance and loudest-speaking Telephone yet known in the World, as supplied to Her Majesty’s Post Office and other Governments; as also the Electric Life-preserver, specially suited to Cyclists” (Falkirk Herald 13 May 1899, 1).

The manager was a Mr Howell and the company clearly had ambitions. That June he wrote to Falkirk Town Council to ask for permission to put wires for the purposes of electric lighting in different parts of the town. The Council recognised that this was a back-door attempt to create a vested interest in an electric lighting order and thanked Mr Howell before declining his offer. Electric Lighting Provisional orders were going through parliament for Arbroath, Hawick, Kirkcaldy and Musselburgh. Worse still from a Falkirk point of view, Stirling was pressing on with its own scheme and it was inaugurated in March 1900. Falkirk Town Council had to act.

As it happened, Edmonstone’s Electricity Corporation (Ltd) in October 1899 once again asked the Council to approve of its applying for a Provisional Order to light the town with electricity. They stated that they would supply light to the town at 3d per unit, and mentioned that they had carried through electric lighting schemes in a great many towns in England, and in Galashiels, Hawick and Brechin in Scotland. In the event of the town desiring to take the works over after fourteen years, that could be done on the Corporation paying the cost price plus 15% for goodwill, if it chose (Falkirk Herald 4 October 1899, 5). Keen to keep the price down, the Council asked the Electricity Corporation if it would include a destructor in the works so that domestic rubbish could be used as a cheap fuel and it would make a saving in the disposal of that waste. A quick response was made stating that it could, though most places found it better to have such a destructor some distance outside of the town. The Edmonstone Electricity Corporation Ltd clearly thought that Falkirk Town Council was prevaricating and so in July 1900 it informed the Council that it intended to apply for the Provisional Lighting order with or without its permission. If the Council opposed the Order it would be obliged to provide an alternative within two years.

Shops too had little confidence in the Town Council and were pressing on with the provision for their own premises. The bootmakers, J Watson & Sons, had its new premises on the High Street fitted out by Thomas Laurie & Co. In the basement was a Crossley gas engine and dynamo for the lighting of the building which consisted of about 70 incandescent lights of 16-candle power (Falkirk Herald 23 June 1900, 5).

The electricity companies were now pushing their power stations with vigour and July 1900 also saw the North British Supply Company of South Shields making application for the power supply to Grangemouth. There was also another project in the pipeline which compounded the urgency of the situation n Falkirk. The Town Council had agreed to a proposed electric tramway passing through the town and calling at Grahamston, Bainsford, Carron, Stenhousemuir, Larbert and Camelon. Finally, after much discussion, in November 1900, an application was made to the Board of Trade for a Provisional Order by Falkirk Town Council for power to:

“introduce a system of electric lighting into the town. Authority is asked by the Council to produce and supply electricity for all public and private purposes within the limits of the burgh of Falkirk, and in order that they may do this power is sought to appropriate lands and property, to erect the necessary buildings and machinery, to open up streets, and to provide appliances and apparatus for the manufacture and distribution of electricity. Power is also asked to authorise the Council to transfer to any local or other public authority or company all the powers and liabilities given to or imposed upon them by the Order. The name of the street within the area of supply in which the Council propose that electric lines or distributing mains for the purpose of general supply be laid down within a period to be specified in the Order is the High Street…”

It was March 1906 before David Kennedy, the president of what was now called the “Falkirk Merchants’ Lighting Association,” had negotiations with the Town Council over the latter taking over the Association’s plant. In subsequent years that group evolved into the Falkirk Merchants’ Association aimed at fixing the opening hours for shops and liaising with the Council over such things as pavements and road usage.

Bibliography

| Jamiseson, J. | nd | Allandale Cottages: Reminiscences. |

| Lumsden, J.G. et al | 1898 | Falkirk Past & Present: Town Mission Bazaar. |

| Martin, P. | 2013 | ‘The Quarter Pit Disaster; explosion, response and community in Dunipace and Denny,’ Calatria 29, 103-120. |