SMR 1407

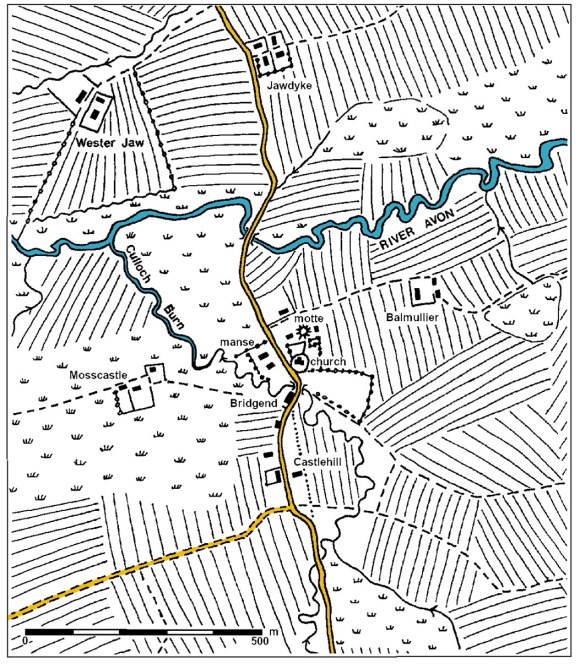

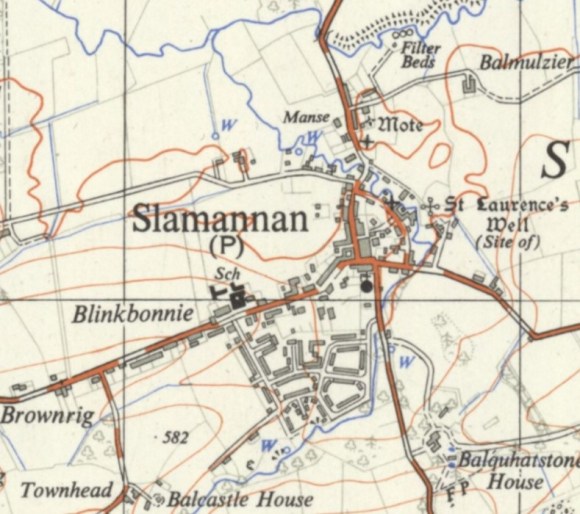

Slamannan is located 6 miles south-south-west from Falkirk at 500ft above sea level. The old medieval parish church was built adjacent to a 12th century motte at an important crossing of the River Avon. This then was the centre of temporal and ecclesiastical power in the parish, with a small hamlet in the bailey to its south and east served by malting kilns at Kill or Kiln Hills. Until 1730 the parish was bounded on the north by the river. At that date a portion of Falkirk parish was annexed to the parish of Slamannan, otherwise known as St Laurence. The parish was about six miles in length from west to east, by three miles in breadth.

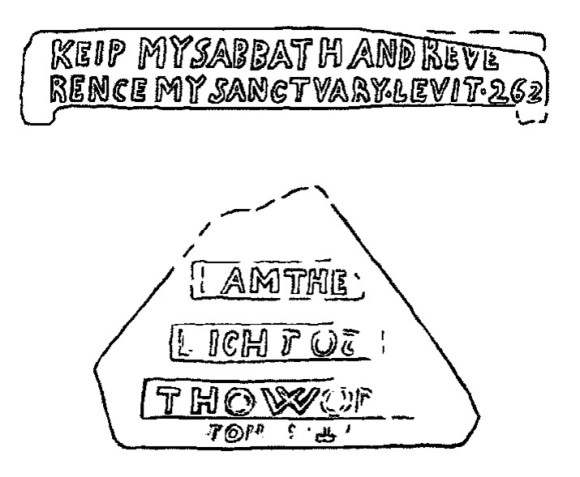

1 – Door or window lintel carved in relief “KEIP MY SABBATH AND REVE/RENCE MY SANCTUARY. LEVIT.26 2”. This is taken from Leviticus 26.2 and the full verse reads “Ye shall keep my Sabbath, and reverence my sanctuary: I am the Lord.” (length 1.68m).

2 – Dormer pediment carved in relief set in three rectangular panels “I AM THE/ LIGHT OF/ THE WORLD”. Below this is carved “JOH—-“ for John 8.12 (length 1.22m).

Until the nineteenth century the population of the parish was very sparse and was widely dispersed. It was almost entirely occupied by agriculture. The land is of relatively poor quality and the parish continued to pay rents in kind – hens, cheese, hay and the like – long after most parts of central Scotland had made the “conversion” to monetary payments. Likewise, the parish was backward in the reform of its feudal obligations and remained astricted to the baronial mills until towards the end of the 19th century.

| DATE | POPULATION |

|---|---|

| 1755 | 1,209 |

| 1795 | 1,010 |

| 1801 | 923 |

| 1811 | 993 |

| 1821 | 981 |

| 1831 | 1,093 |

| 1841 | 979 |

| 1851 | 1,665 |

| 1861 | 5,850 |

| 1891 | 6,731 |

| 1901 | 5,286 |

| 1911 | 3,443 |

| 1921 | 3,409 |

| 1931 | 2,959 |

| 1951 | 3.004 |

| 1961 | 3,311 |

When the first Statistical Account was published in 1795 there was no village in the parish and the tradesmen were widely distributed throughout the area. These included 4 smiths, 10 masons and joiners, 12 weavers, 12 shoemakers, 3 tailors, 3 millers, 1 lint-miller, and 2 flax-dressers. There was also a minister at the church and a schoolmaster close by (McNair 1795). There was no baker and bread for the communion had to be obtained from Linlithgow.

The population of the parish had hovered around the one thousand mark for a century and little had changed by 1840. The New Statistical Account of 1841 remarked that :

“In this parish there are no villages, only three places where there are a few houses, close by the church, Balcastle, and the other to the east of the parish, where two roads intersect each other, and gives to the village the name Cross Roads.”

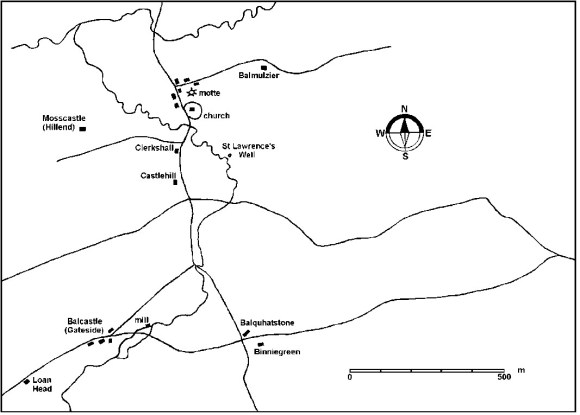

Balcastle housed the baronial mill and this attracted a huddle of thatched dwellings. This hamlet was also known as Gateside, which simply means “road side” and often refers to one of the main through roads. Up to the early eighteenth century this road provided a southern route from Glasgow to Edinburgh. It had been used by Cromwell’s army in 1651. East from Balcastle it crossed the Avon at the mill and proceeded to Balquhatstone House and on to Pirney Lodge (most of this last section later forming a private drive for the big house).

By 1690 there were nine Grammar Schools in Stirlingshire and Slamannan had one of them. These were schools where Latin or Greek were taught. Slamannan was unusual in that due to the lack of an urban centre the place where the school was held alternated annually between the west and the east ends of the parish. These premises were leased as occasion arose and it was only in 1695, when no private property was available, that the Kirk Session bought land at Kirkburnhead upon which to erect a school building.

The Heritors, however, refused to pay for the building of a school and instead the schoolmaster, Donald Archibald, appears to have built a private dwelling at Kirkburnhead and rented out a room for the use of the scholars. It was known locally as the “Slate House” – the use of slates rather than thatch or tiles for the roof being rather unusual at this date.

The two storey house had a lintel over the door bearing the date and initials “17 D A M S 76.” The house was properly named “Clerkshall,” a name probably derived from the appointment of the schoolmaster as the Session clerk. It appears as such on Forrest’s plan of the parish in 1806. The building was taken over by the Kirk Session in 1803 and in 1808 the school settled in there permanently.

In 1810 the old church was demolished and the hill upon which it sat was levelled for a new building. The scatter of houses now spread from just north of the motte in the north to Castlehill in the south. Castlehill (later called Calton Hill) seems to have been named after a prehistoric fortification which had occupied the hill there and of which there were few traces even then.

The minister in 1841 noted that :

“There are few parishes where so little change has taken place since the last Statistical was drawn up, as in this parish. There have been no new roads, no public works, and no manufactures of any kind in the parish. Agriculture, however, has undergone a most decided improvement.”

The agricultural improvements were being pushed by reforming landowners like Ralston of Ellrigg and Stone of Bankhead. Their new enclosures diverted the courses of the public roads in the vicinity of their estates, often moving them well away from their mansion houses. All around changes were happening almost imperceptibly. From the west the old road had run from Todbughts, via Drumriggend and Southfield, to Balcastle. By 1760 a new track diverged from Todbughts to pass by Greenhill, Middlerigg and Brownrigg to meet the Limerigg-Falkirk road a little to the south of Castlehill. It was around 1835 before Waddell closed off the main road eastward from Balquhatstone House and replaced it by one further to the north, linking up near Castlehill with that from Brownrigg and creating a new crossroads. The improved roads were important as it was along these that the agricultural produce was taken to the markets in Falkirk and Airdrie.

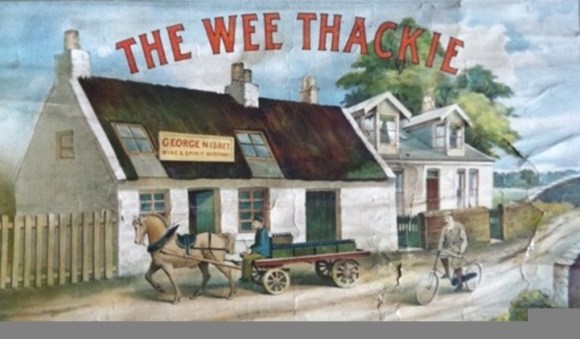

A little to the north of Clerkshall was a long low building with whitewashed stone walls and a thatched roof. For this latter reason it was known locally as the “Thackie.” From a very early date it served as a hostelry – one of only three in the entire parish in 1795. It was just south of the bridge over the Kirk Burn and for that reason the proper name of the building was the “Bridgend Inn.”

There was now a church, a school and a public house – but very few dwelling houses. A hundred yards up the stream was a holy well, named after the patron saint of the parish. It was just a few yards from the north bank of the stream and provided purer water than that water course. This was a well for travellers and pilgrims rather than the local people who would have used the streams for convenience. Once such travellers ceased it was utilised for a bleachfield where the locals could spread their cloths out on the south-facing slope and bleach them in the sun using sour milk before using the copious water to rinse them out. The effluent then entered the stream and thence the river. Perhaps it was appropriate then that the name of the stream should be changed to that of the “Culloch Burn,” which is a corruption of “coal heugh burn” and is first found in 1848 (Reid 2009, 173). Before long it was also polluted with coal dust.

Away from the main roads transport was difficult; a situation described in 1836 :

“there are no cart roads, and in some places the farmers are obliged to carry the produce of their farms on horses’ backs to the nearest parish road where carts can be had…” (Macneill 1836).

This situation could be used to the advantage of some locals and illicit whisky stills were rife in the area. In May 1811 John Bell, the supervisor of excise at Bo’ness, and his officers, demolished stills in the hinterlands of Kilsyth, Shieldhill and Slamannan (Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser 7 May 1811, 3). This did not stop the practice and in November 1844 an illicit still of “considerable” capacity was seized in a field a little to the south of Slamannan village. The spirits were being distilled from strong ale. It was in full operation at the time of seizure and some young men working it made their escape, except one who was lying drunk on the floor.

The spirits were all poured out onto the ground, and the utensils were conveyed in a cart to Falkirk (Stirling Observer 28 November 1844, 4).

Coal had been worked on a small scale throughout the parish in the early 19th century, but the difficulty of transport meant that it did not travel far. Some of it was good steam coal and therefore should have brought a good price. As early as 1805, when the Lands of Limerigg were advertised, the coal was seen as a major asset and thought was given about how it could be taken to the markets:

“The lands of Limieridge are all inclosed and subdivided; they abound with coal of the best quality, which can be wrought at little expence; and as they adjoin the Blacklock, which supplies the Monkland Canal with water, the coal can be transported to Glasgow at a small expence…” (Caledonian Mercury 22 April 1805, 4).

However, it was 1835 before nine businessmen (one of whom was Robert Ralston of Glen Ellrigg) pushed a Bill through Parliament to construct a railway through the area. It was stated that the railway would be :

“of great local and public utility, by opening an easy and cheap means for the conveyance of coal, lime and manure in the neighbourhood of such railway, and of coal and ironstone, and other minerals, to the said canal, from where they may be carried to Edinburgh and other parts, and also to the said Ballochney Railway, by means of which, and the subjacent railways and canals, they may be carried to Glasgow and other parts.”

The Act for the 12½ miles long railway was passed on 3 July 1835 and construction began the following year.

The Slamannan Railway opened at the end of June 1840. The people of Slamannan were elated and the minister optimistically wrote:

“Greater facilities will now be furnished for promoting the general industry and prosperity of the parish, by means of the railway passing obliquely through the parish… The railway being now finished, and a year nearly in operation, the minerals have become an object of acquisition, the parish will increase in population by the erection of villages, and thereby an additional stimulus will be given to agricultural pursuits…

Since the commencement of the railway, there have been different bores made on the lands of Balquhatstone, for ascertaining the nature of the metals, and after a depth of 25 to 30 fathoms and upwards, there have been found several seams of coal from 1 to 3 feet thick. A pit has lately been opened, and a steam engine erected by Messrs J. Russell of Leith, tacksmen of the coal; and at the depth of 12 fathoms have found a seam of good coal, 3 feet thick, with a free-stone roof. About twenty-five workmen are employed, and nearly fifty tons daily of coal are conveyed to market by the railway, the selling price being 4d. per cwt. on the hill. Other trials in different districts of the parish have recently been made, and smithy-coal and abundance of fine freestone have been found. Over the whole of the parish as well as the Annexation, there is abundance of coal and ironstone, which is accounted valuable, yielding 33 per cent.; and the Strathavon yields ironstone of 36 per cent, and coal 17 per cent., according to the analysis of Dr Hugh Colquhoun. The only going coal at present is on the lands of Balquhatston and the Lodge, and rents at £25 annually.”

The pace quickened and over the following decade a huge number of pits were opened up. Activity was frenetic and Slamannan became like a frontier town in the wild west of America with new labourers arriving daily in the hope of work. In the first decade an additional 700 or so people arrived and in the second decade a further 3,000! Housing had to be provided quickly and cheaply and in most cases this meant building brick rows near to the pit heads. Hamlets sprang up all over the area.

Things were also changing in the village of Slamannan. Writing in 1860 the Ordnance Surveyors noted that most of the houses in the old village near the church were :

“one storey, thatched and tenanted by agricultural labourers.” They then went on to say that since 1840 “the importance of the village has considerably improved, both in size and appearance. A number of substantial two storey houses having been erected, the ground floors of which are used as shops.”

These included a post office and two public houses. The village had become a service centre for the dispersed collier settlements.

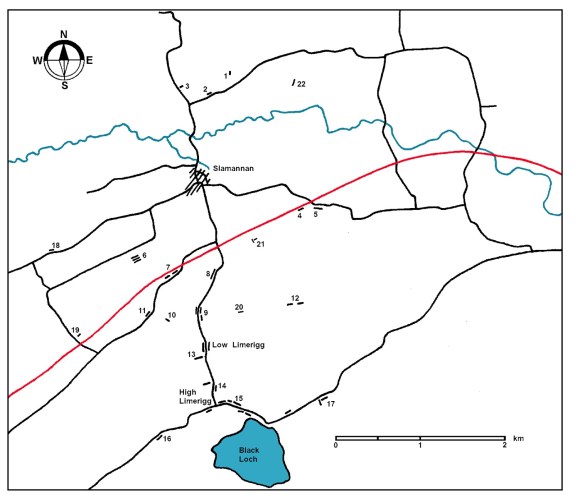

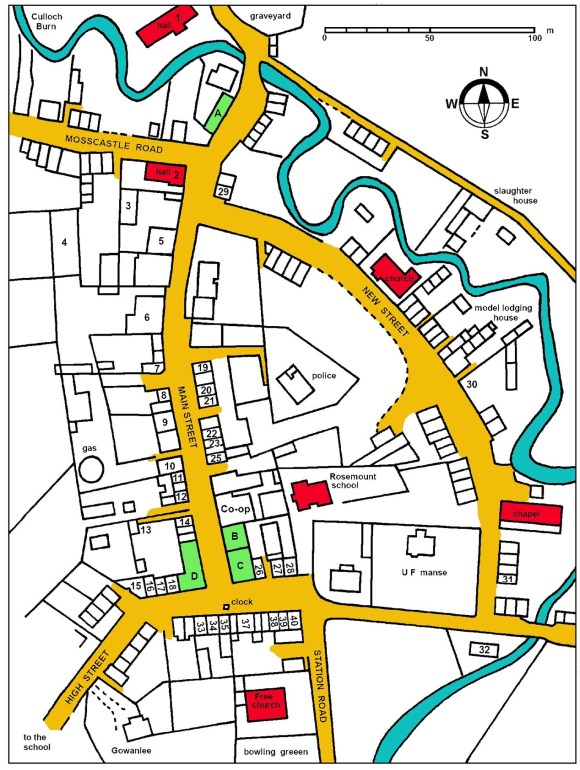

1 – Stanrig (Dawson City); 2 – Nappiefaulds; 3 – Dyke; 4 – Slopside; 5 – Arnloss; 6 – Southfield; 7 – Binniehill (Ham & Egg); 8- Station; 9 – Burn;

10 – Thorn (Peeweep); 11 – Newfoldyke; 12 – Drumclair (School & Quarry); 13 – (Long); 14 – (Tarry); 15 – Lochside; 16 – Lochend; 17 – Barnsmuir; 18 – Greenhill; 19 – Lodge; 20 – Salterhill; 21 – Balquhatstone; 22 – Strathavon. The sites of Porch, Red and Woodside Rows are not shown.

In 1851 one of the oldest inhabitants of the village described the changes that had taken place over the previous 30 years. At the commencement of that period he says:

“The minister and schoolmaster, the inn-keeper, the hoary-headed sexton, comprised the whole population; now there are two clergymen, two schoolmasters, a doctor, a midwife, and 52 families. Then there was no grocer, no baker, no butcher – the place being supplied by a bread cart once a week. Now there are bakers, grocers, and butchers; smiths, wrights, and shoemakers; tailors and seamstresses in abundance. Then the one low-thatched tavern dispensed its 40 gallons of spirits… now there are three, from the thatched tavern to the comfortable inns. Then the letters had often to lie a whole week in Falkirk post-office, now there is a daily delivery. With all these changes, and many more, morality, as too often happens in such cases, has not improved in a corresponding ration” (North British Daily Mail 3 January 1851, 4).

The coming of the collieries had resulted in a huge increase in mail for Slamannan and late in 1847 James Wilson, who ran a grocery business there, became the first sub-postmaster. Daniel McDougall was the trusted post-runner. A bag was now made up at the Falkirk office and despatched to Slamannan at 9.45am (box closing at 9am); and a bag left Slamannan at 4pm, arriving at Falkirk about 6pm (Falkirk Herald 13 January 1848, 3). James Wilson died early in 1857 and his widow, Margaret Wilson became the sub-post mistress until giving up the position in November 1859.

Ella Watson, sub-postmistress, stands in the doorway of the post office. The postmen include Paddy Kelly to the left of the door, and Mr Russell to the right. The sign above the door reads: “Post office for money order, savings bank, parcel post, telegraph, insurance and annuity business.” In the doorway of Watson’s outfitters is young Willie Watson holding a cat.

The new sub-post master was Alexander Brown, who had a baker’s business in the village. The 1860 Ordnance Survey map shows the Post Office on the north side of the High Street, just to the east of the Cross, and it was to remain there until the early 21st century.

Most of the new building took place on the Lands of Castlehill belonging to Provost Walter Rankin of Auchengray (he was provost of Airdrie). His family had owned the lands for generations and he was now in a position to profit from their development. It was his readiness to feu the land that led to the new village growing up at the crossroads a little to the south of the old one. The land in between the two sites was owned by the Waddells of Balquhatstone who were less willing to part with it.

The three taverns mentioned in the 1851 report were the Thackie, the St Laurence Inn, and one at the north end of the village which was latterly known as the “Fit o’ the Toon.” The St Laurence occupied the north-west corner of the crossroads and appears to have been a speculative build in 1846 by Provost Rankin. It is built of the local hard brown whinstone with dressed sandstone margins – a distinctive style once common on the Slamannan plateau. The two-storey building continued northwards along Main Street and included a hall, stabling, a coach house, and offices. The ground floor was occupied by the public house and before long had a bottling store, washing house and wine cellar. James Wilson took over the inn and then acted as the host. As well as drinking, many activities took place here – such as dinners, business meetings, social meetings, auctions and sequestrations. Around 1855 the two-storied building was extended westwards as a tenement with accommodation upstairs and a provision shop below. At the same time Wilson played the lead in constructing a gas works in the grounds behind the inn which it served. John Spence, gas-fitter and brass-founder in Airdrie, acted as the engineer and fitter. The works was large enough to provide gas to the neighbouring houses and shops. When it and the inn were sold on in 1859 it was stated that :

“Pipes have been laid into nearly the whole of the houses in the village and neighbourhood, and numerous buildings are being erected every year, thereby increasing demand for Gas” (Falkirk Herald 11 August 1859, 1).

The St Laurence Inn was soon seen as the centre of the village and in 1851 the farmers and cattle dealers of the area got together and resolved to hold two fairs or markets a year at Slamannan for the sale of horses and cattle. The site selected was the broad open area to the south of the St Laurence Inn. They were to be held on the first Tuesday of May and the first Tuesday of November, or thereabouts. The animals could be brought to the fair by rail and taken away the same way, the station being just a quarter of a mile to the south. The market got off to a good start and although attendance varied, it prospered for several decades. The second of the year’s fairs were also used for hiring farm labourers and the day was generally observed as a holiday. They attracted many visitors keen to see the sights, which included travelling shows. In 1856 Alexander Walls uttered a counterfeit half-crown piece, knowing it to be false and counterfeit, at the November Fair to the wife of a showman who was exhibiting mechanical figures opposite to the inn. He was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment (Stirling Observer 1 January 1857, 3). These markets continued until the late 1870s when they were replaced by cattle shows organised by the Slamannan Agricultural Society on the Glebe Park to the north of the manse.

The new shops and houses opposite the St Laurence Inn had been deliberately set well back to create this market ground. Indeed, for this purpose the road southwards had been moved to the east so that the Cross presented a T-junction rather than a crossroads. In 1857 the open space was referred to as “the Common” and it was suggested that a public well should be sunk there (Falkirk Herald 12 February 1857). That April there were 100 head of cattle and 30 horses sold at the Fair.

The village had grown like topsy and little provision had been made for the water supply or drainage. Most water still came from the Culloch Burn but for drinking purposes a number of private wells were sunk. In 1854 there had been a drought and many of the wells had dried up. The streams were polluted – not as you might expect from the coal extraction (that was to come later), but from the farmers soaking their crops of lint in them! Public wells already existed near the church but only two were added to the expanding village. These were Castlehill or Bank Street Well, and Brownrig Well (see Wells & Fountains of the Falkirk District).

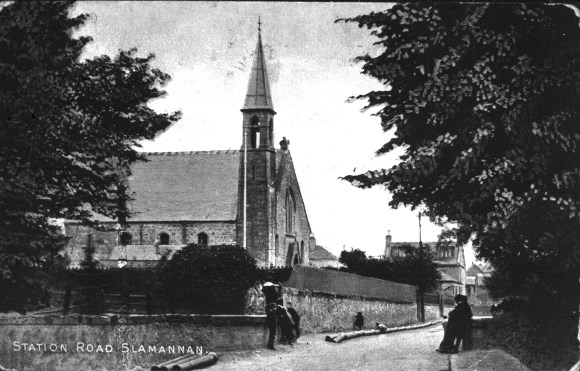

The increase in the number of souls in the parish naturally commanded more attention from the church. By their adventurous nature most of the incomers favoured the Free Church after its formation in 1843, with Baptists and Catholics also present in significant numbers. At the Disruption the entire Kirk Session of Slamannan had resigned and the following year, on 18 February, a Free Church opened well to the east of the village near Pirnielodge. The congregation prospered and was eventually able to build a more substantial church in the village on Station Road.

Just as important for a service centre was the establishment of a bank. In 1857 the City of Glasgow Bank announced that it intended to build a bank in the High Street immediately to the west of the St Laurence Inn. However, the bank was hit by a financial crisis and the project was delayed. Instead, the City of Glasgow Bank rented a house and garden from Margaret Wilson, the sub-post mistress. This was presumably adjacent to the post office mentioned above.

Large investment was needed to get the coal industry established and although fortunes were made by some coal masters, others lost them. In February 1842, John Miller Russell (noted above) was declared bankrupt. Traditionally the first of this new breed of coal masters in Slamannan was John Johnstone who lived at Burnhouse to the south of the village. He made enough money to build Rosebank Cottage for himself in what became Bank Street (he died there on 21 August 1859 aged 84).

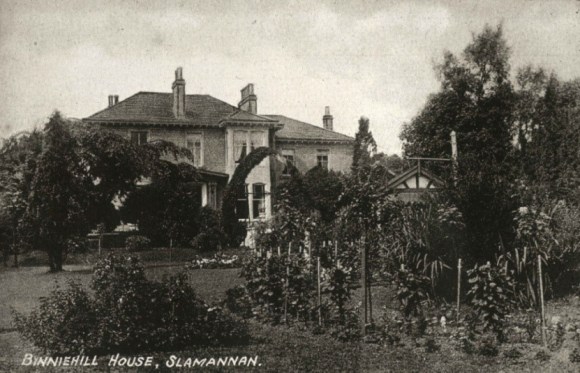

Further down the road, Balcastle Villa, was erected in 1857 for William Scott of the Jawcraig Colliery. Next door to it was Binniehill House, also constructed in 1857, for Dr John Brown of the Binniehill Coal Company. Between Binniehill House and the Main Street was Stratton House.

This had been erected about five years before for George Waddell, another coal master who lived at Binniehill Cottage. Stratton House was rented out to John Russell, a wright, builder, and carpenter, and had been kitted out with an engine and machinery for a cart shop. George Waddell also possessed four other dwellings in the village, probably in the High Street, and all of these were sold off in 1859.

In 1860 the principal coalworks in the parish were those of Binniehill and Strathavon, belonging to Dr Brown; Jawcraig Colliery, Scott and Co; Nappie Faulds, Mathew Hay and Sons; Arnloss, Mr Watt; Drumclair, James Nimmo; Balquhatstone, Mr Watson; Limerigg, Mr Simpson; and Southfield, let by Provost Rankine to Mr Black, Whiterigg.

The coal masters employed professional men such as colliery managers and surveyors and these occupied the smaller single dwellings in the village. One essential for a heavily industrialised area was a man of medicine and Dr John Boyd moved to Slamannan in the early 1850s. He was soon very busy as accidents at work were commonplace. Around 1855 he had the residence at Gowanlee built (at that time it was only one storey high). He was an expert on phrenology and often lectured on the functions of the brain, but spent most of his time dealing with mutilated bodies. He was soon joined in Slamannan by Dr J C Nash who resided at Rosemount, just to the east of the post office. The two men were kept busy.

The vast majority of colliers lived beyond the confines of the new village in miners’ rows scattered across the countryside. The village itself was now made up of three distinct areas. First, to the north, was the old settlement with its single storey thatched dwellings, the Thackie, the 1810 Church, and the 1776 School building.

The approach from Falkirk was radically altered when a new row of single-storey houses was erected opposite the Manse in 1856, and then in 1858 the old manse was demolished and a new one, more becoming to the cosmopolitan minister, Robert Horne, was built just to its north.

Secondly, to its south of the old settlement, was the core of the new village stretching along Main Street with numerous shops and service suppliers. These included bakers, tailors, seamstresses, drapers, wrights, tinsmiths, bootmakers, shoemakers, postal workers, blacksmiths, grocers and butchers. An impression of the number and range of such businesses may be gained by looking at the plan of c1920 below. The upper floors of the shops were residential with flats above rented out to colliers and labourers.

It was also here that the new public houses were located – joined in 1866 by the Royal Hotel on the north-east corner of the Cross, John Boyd, publican. This was a fine-looking building of two storeys, of sandstone ashlar with a hood-moulded doorway. It completed the aesthetics of the commercial centre or Common.

In the hinterland behind the shops were the workshops, the gas works, bake-houses, stables, washhouses, and yards. Here in later years were to be found a biscuit factory and a confectionery works.

Blacksmiths were very important in this rural community. They shod the numerous horses, repaired farm machinery and household gadgets – even inventing new ones, and provided many purpose-made items that the ironmonger could not. Latterly their main task was to service the mines. At one time there were no less than six smiddies in the parish, three at Avonbridge, one at Crossroads and two in Slamannan. Perhaps the best known was that established by Robert Taylor a little way down the Avonbridge Road. In the early 1860s he was joined by Charles McLean who married his daughter, and in 1903 they left the business to their son Angus. Smithing continued until the Second World War with Angus the last working blacksmith in the parish.

The shops sold almost everything that was wanted in the village. One surprising commodity on offer was gunpowder! In July 1876 Robert Smith, who was described as a “grocer in Slamannan,” was found guilty of contravening the new Explosives Act. He was licensed under the Act to keep 50 lbs of gunpowder in a wooden erection at the back of his shop, but was storing 87 lbs in excess of that quantity (North British Daily Mail 11 July 1876, 3).

The third part of the village belonged to the elite – the coalmasters, doctors and builders. This included the substantial houses of Gowanlee, Binniehill, Balcastle, Stratton, Rosebank, Rosemount, and Prospect View.

By the time that the Ordnance Surveyors arrived in the area in 1860 Slamannan had all the appearances of a small town. Two churches, two doctors, plenty of shops, and two public houses. It even had a police officer – James Simpson Stewart. A second policeman was sanctioned in 1864, but it was 1879 before a police station and lock-up was opened at a cost of £1,004 on Castle Hill. The Free Church building was rather small and remote and so in 1860 a new building was started on Station Road on land donated by Mrs Waddell of Balquhatstone. It opened on 4 August 1861, having cost £850. Just four years later it was gutted by fire although the contents, including the seats, were saved. Notwithstanding the disaster it was rebuilt the next year.

There were also a number of clubs and societies in the village. One of the first was the curling club which was formed in 1840 and played on the Black Loch or on Ellrig Loch when they froze over. Over the following decades they played against clubs at Muiravonside, Torphichen, Falkirk, Polmont, Larbert, Linlithgow, Motherwell, Whitburn and Stirling. In common with many clubs it then constructed its own artificial pond at Kirkburn on the north side of the Culloch Burn. By the early 1860s there was an annual games’ day for athletic sports held on the glebe. This event continued for over a century and a football field was laid out. Indoors there were the meetings of the Mutual Improvement Society established in 1861. Each year a series of edifying talks were held to encourage self-improvement and a scientific interest in the world. The favoured pastimes of the miners were quoiting and hengie – both of which could involve a certain amount of gambling. The latter, also known as bullets, involved throwing a stone ball along the public roads over a set course, with the team taking the least number of throws winning. Needless to say it was banned by one of the many Road Acts and in May 1875 one of the Slamannan miners was fined for playing it (Stirling Observer 20 May 1875, 6).

Of course on pay day the miners congregated in the evening in the hostelries, where fights often broke out. The drink habit was undoubtedly strong in Slamannan – but not as bad as was reported in the newspapers in January 1889 which claimed that 300 people there had consumed 1,000 gallons of proof spirit in the last sixteen months (Glasgow Evening Post 8 January 1889, 4)! Whilst there were only around 300 people living in the village there were another 2,000 or so in the miners’ rows within a mile. It was partly the drink that led to another disgusting pastime – that of wife-beating. Not surprisingly, a branch of the Total Abstinence Society appeared in Slamannan around 1865. The setting up of a Masonic Lodge in Slamannan in 1868 was also an attempt to moderate the extreme behaviour and to gain influence further afield. The new hall (a room in the Royal Hotel) of Lodge St John 484 was consecrated on 22 February 1869.

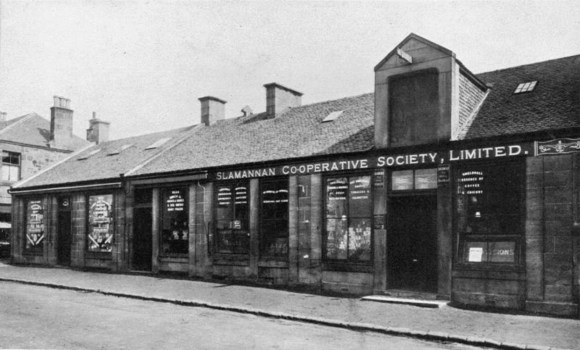

Perhaps the most important institution of this period was the Slamannan Industrial Co-operative. It is said that one day after work in 1860 a handful of colliers met on the Water Green in Slamannan and discussed the new co-operative movement then making the news in Rochdale. They decided that each of them would put ½d into a central fund so that they could send a letter to Rochdale seeking for information. More pennies and much more correspondence left them in such a state of knowledge that on 6 February 1861 the Slamannan Industrial Co-operative Society was registered.

Collectors were appointed for each of the miners’ rows in the district and subscriptions of between 6d and 1s were collected until sufficient funds were accrued. A large double shop at Yankee’s Land in the Main Street was leased for five years and on 7 June it was opened with 221 members and a subscribed capital of £187.15.6. The initial stock was a mere £100 worth of goods and trade was slow.

Difficulty was experienced in obtaining bread of consistently good quality and so it was supplied by the Airdrie Bread Society. A major break – and stimulus – to the development of the Slamannan Co-operative was a miners’ strike in September 1862 which lasted for eight weeks. During this time there was much hardship amongst the miners and many had to withdraw their capital from the Co-operative Society to tide them over. But they quickly realised how important that investment had been for them. More strikes followed – nine weeks in 1878, eight weeks in 1879, five weeks in 1887 and thirteen in 1894. Each reinforced the Society’s role. When interviewed by a newspaper reporter one of the strikers noted that :

“the store is the real saving bank for us… it may interest you to know that one of the best things we have is our Co-operative Store. It was got up and is maintained entirely by ourselves. There are about 1,500 members, and we have two shops here in which everything we need is sold except cloth and boot and shoes.”

Before long the Slamannan Co-op also sold cloth and footwear and opened branches in Limerigg, Longriggend and Avonbridge. It had a slaughter house at Kirkburn, and a large-scale bakery near the station.

Gaps in the village were slowly filled in with yet more buildings. In 1864 the Road Trustees reduced the steepness of the hill on Main Street to the south of Clerkshall. This enabled a new road to be taken off the east side of Main Street in the early 1870s. It ran parallel with the Culloch Burn until it met with the road to Avonbridge. Appropriately this was called “New Street” and was opened up for feuing.

The Wesleyan Methodist Church was completed here in 1874. Before long there was a large population of miners living in the street. It was at this time that the hill between New Street and the Main Street was rather grandiosely called “Calton Hill,” after that in Edinburgh.

By 1880 it was not uncommon to see Slamannan referred to as a “town.” Each year empty sites in the village were built upon. In 1888, for example, Dr Waddell erected six single houses at Bridgend, Mr Wood rebuilt Prospect View, and a cottage of four apartments was built at Blinkbonny.

One of the most widely-known shops on New Street was that run by William Gardiner for herbal medicine. He was there for over 20 years and in 1904 published a book called “The Working Man’s Guide to Health by Herbal Remedies.” Gardiner even treated patients by post. His lengthy adverts started:

“Member of the National association of Medical Herbalists of Great Britain, and of the Society of United Medical Herbalists of Great Britain. BOTANIC DISPENSARY, New Street, Slamannan, supplies of all kinds of garden and flower seeds, Dobbie & Co’s seeds (Rothesay), herbs, barks, and roots, and herbal medicine all kinds, and patent medicines of all kinds…”

The Slamannan Parochial Board had been created in 1845 to administer the Poor Law. As the nineteenth century wore on, greater attempts were made to organise and regulate society in order to improve the living conditions in Slamannan. Open gutters along the sides of the public roads conveyed not only rain water but also sewage and had become a nauseous nuisance. So the Parochial Board established a special district under the Board of Supervision, in terms of section 24 of the Public Health (Scotland) Act, 1867, which they called “the Local Authority of Slamannan.” Its purpose was to oversee the laying down of new gutters and an underground sewer in front of the premises owned by James Rankine – publican (the St Laurence Inn), James Kincaid – blacksmith (Stratton Cottage), John Dickson – innkeeper (Royal Hotel), and James Forrester – tailor. These are on the north side of the High Street at the Cross and presumably the sewer led to the Culloch Burn. The scheme went ahead and John Dickson refused to pay until taken to court when it was shown that the Authority had been properly constituted. It was to be 1930-33 before Stirling County Council introduced a comprehensive scheme of sewers for the entire village.

Following the Education Act for Scotland of 1872, a school board was established for the parish in 1873. Rather than upgrade and extend the existing buildings it decided to find a new site and to construct a much larger edifice to accommodate 350 pupils. The new school opened at the west end of the village on 11 September 1876. The staff at the time of the opening consisted of Mr Horne (head teacher), Miss Hutchison (female teacher), an assistant, and three pupil teachers.

There were no sewers in this part of the village at this time and so septic tanks were in use. Water was probably collected from the roof in barrels, as it was at other schools.

James McKillop, coalmaster, who lived at Binniehill House, was at a meeting of the School Board when he heard that the miners in the area were rioting and ransacking his home at Binniehill House. It was 18 April 1878 and after weeks of strikes, the other coalmasters had started to take action to have the colliers evicted from their homes. A crowd of angry men, women and children gathered near Limerigg and then marched on the village at Slamannan. On their way they smashed all the windows in the signal box and railway station. In the village the house of another coalmaster, James Gemmell, was given the same treatment and the door all but broken up. Then the mob turned to Binniehill House. Not only were all of the windows destroyed, but some of the rioters entered the house and broke up the furniture whilst those outside tore up the garden. James McKillop received news of the disturbance around 9.30pm and upon his return home found it a complete wreck. Mrs McKillop with her children and servants had taken refuge in a neighbour’s house – they were scared and frightened

It was a difficult time for the village. In 1877 the City of Glasgow Bank had moved into Balcastle Villa, but the following year the bank failed and its depositors lost a lot of their money. The building in Slamannan was subsequently taken over by the Bank of Scotland.

Remarkably, James McKillop and his family returned to Binniehill House and lived there for many years. He continued to play an active role in the social and political life of the area. He became a road trustee and a justice of the peace. With the Slamannan Angling Club he helped to restock the River Avon with trout. He was, however, destined for higher political life and was elected a county councillor and then as MP for the county and remained in Parliament until 1906. Four out of five of the Slamannan miners voted for him! Whilst an MP he returned to Slamannan on numerous occasions, often delivering speeches. Some of these are recorded in his books – “Observations by the Way” came out in 1884 and includes a visit to Pompeii as well as papers on moral, social and religious questions; “Thoughts for the People” published in 1898, has his talk on “selfishness,” highlighting the gulf between capital and labour.

The campaign to extend voting rights was at the heart of the reform necessary for a more just society and on 11 September 1884 one of the largest demonstrations in Scotland in favour of the Franchise Bill was held in Slamannan. A general holiday was observed, and a very large number of people took part in the proceedings, which included a procession of the trades and a mass meeting with the inhabitants. The streets were decorated with flags and evergreens. The 2,000 strong procession mustered at 11.30am at High Limerigg and marched with several brass bands, flags, banners and models, to Mosscastle at the north end of the “town” for the mass meeting. Here several dignitaries delivered rather lengthy speeches (Glasgow Herald 12 September 1884, 9).

2,000 men mustered again in January 1886 – this time with a flute band at the Cross. On this occasion they were striking miners and the speeches were by their leaders. They were watched over by a large contingent of police intent on avoiding the riots of previous occasions.

The roads too were slowly improved, though it was only in 1889 that a steam roller was sent to Slamannan to compact the roads, as it had been thought that it was too heavy to traverse the mosses. In April of that year Alexander Kidd started a passenger service from Slamannan to Falkirk using a waggonette. To undertake the same journey by rail at that time could mean changing trains at Blackston, Manuel and Polmont!

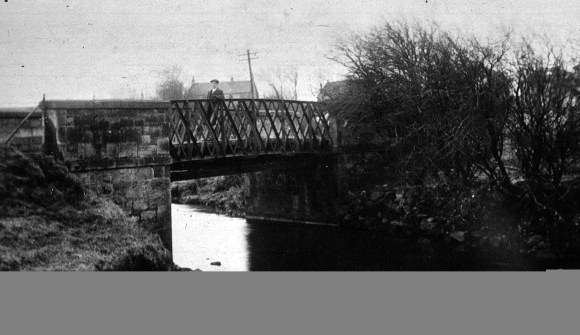

In 1880 the old narrow hump-bank bridge over the River Avon on the road to Falkirk had been replaced with an iron structure. The new bridge had a greater clearance from the water level which was approached by embankments from either side. Prior to this, the road on the north side of the bridge regularly flooded in wet weather, being covered by 2 to 4ft of water, impeding all travel.

The rapid expansion of the coal mining and the consequent increase in population had left the river polluted. One of its tributaries, the Culloch Burn, was particularly bad. It ran past the residence of Dr William Arthur at Balcastle and he and some friends successfully advocated for its purification, resulting in at least two actions being raised in the Court of Session against coalmasters.

In 1881 the local Orange Lodge, which had been formed in the late 1850s, purchased the old School Glebe on the west side of Main Street and built a meeting hall. It was known as the “Ark of God Royal Black Encampment Knights of Malta, No. 56.” Public exhibitions and meetings were held in the hall. A good example of this was in August 1892 when a model of Jerusalem, which was touring central Scotland was put on display there.

For the working classes football became the main outdoor sport with many of the miners’ villages having their own teams. The clubs included: 1870 – Slamannan FC; 1880 – Southfield FC; 1883 – Barnsmuir FC; 1885 – Lochside Athletics FC; 1887 – Slamannan Star; 1889 – Binniehill; 1893 – Drumclair FC, Slamannan Rovers, Slamannan Swifts; 1908 – Blue Bell; 1920s – Slamannan Hearts, Lochside Rovers, Slamannan Athletic, Slamannan Thistle, Slamannan Villa.

The theatre opened by Howard Campbell in a wooden shed in Gillespie’s Yard in August 1892 was another popular spectator activity. With it the village reached the zenith of its service provision. Notice was given in January that year that the Slamannan Coalfield was being rapidly exhausted and there was probably only twelve years work left. New pits were being opened to the east in Muiravonside parish and the miners followed. There was now a prospect of depopulation and businesses had to consider their future prospects.

By the middle of the decade the County Council was delaying its plans to provide water and sanitary facilities until the situation was less fluid. For almost twenty years different sources of clean water were suggested – the two favourites being the Lily Loch south of Caldercruix and East Craig south of Avonbridge. Both had major engineering problems.

Having met in various venues, including the Royal Hotel, the Slamannan Lodge of Freemasons decided to erect a hall of its own in 1901. It was designed by a fellow mason, the architect William Black of Falkirk, and stood on the corner of Main Street and Mosscastle Road. That same year a new hall was opened nearby on the old glebe for the parish church.

A – The Thackie; B – Crown Inn; C – Fraser’s Bar & Royal Inn; D – St Laurence Inn. 1 – Parish Church hall; 2 – Masonic Hall; 3 – Orange Hall; 4 – Pinder’s Hall (cinema); 5 – McAlpine’s (rag-bone merchant); 6 – Laing’s Bakery; 7 – Macchi (Italian chip shop); 8 – Irvine (ironmongery & china); 9 – Smith (baby linen); 10 – Nimmo (boot shop & tinsmith); 11 – Gillespie (plumber & gasfitter); 12 – Bennie – Brodie (butcher); 13 – Wilkie (joiner); 14 – McNiven (cobbler); 15 – Calder (grocer); 16 – Afflik (boot shop); 17 – Brown (newspapers); 18 – Smith (barber); 19 – Fowler (photographic studio); 20 – Grant (saddler); 21 – Dobbie (fruits & sweets); 22 – Brodie (butcher); 23 – McPheat (bicycles); 24 – Boig (wallpaper); 25 – Watson (baby linen); 26 – Baxter (outfitter); 27 – Gentleman (outfitter); 28 – Post office; 29 – Smith (sweets); 30 – Murphy (grocer); 31 – Strang (laundered collars); 32 – Angus McLean (blacksmith); 33 – Logan (fruit); 34 – Rennie (grocer); 35 – (grocer); 36 – Chapman (butcher); 37 – (fruit); 38 – Parish Offices; 39 – Waddel (butcher); 40 – Ting Tong Tea Shop.

The construction of New Street and the infilling of sites along Main Street and Bank Street meant that more miners and their families lived in the village itself – often in single room flats. However, the vast majority of the population of the parish still lived in miners’ rows dotted across the coalfield. To take their services to the people many of the traders from the village had horse-drawn carts that toured the area with fresh produce.

The prosperity of the parish was intimately linked to the output of the pits. The Slamannan miners developed a reputation for their militancy and strikes were not infrequent. There were major strikes in 1862, 1878, 1886 and 1894. The last was the most serious and lasted for around 13 weeks and was part of a national event organised by a Central Committee. Eight soup kitchens were set up in the parish to feed the children of the idle miners, one of which was in the village. The money came from subscriptions from outside of the mining community and after three months was drying up.

The soup kitchen in the village fed 400 children with one meal a day and as it was run by the Wesleyan Methodist Church it was the only one able to continue. Starvation eventually drove the colliers back to work, despite bitter picketing. Slamannan produced a fine quality steam coal and one result of the strike was that the major order from the national railway in Denmark was lost to Germany. The following year Balquhatstone Colliery closed permanently. The loss of income also drove some of the traders away from the village.

When Slamannan Parish Council took over from the Parochial Board in 1894 it was responsible for the Poor Law, the care of the mentally ill, the prevention and mitigation of disease, registration of births, deaths and marriages, vaccination records, burial grounds, and public roads. It could call upon the County Council to form Special Districts for the likes of lighting and scavenging (rubbish collection). Drainage and water supply could be dealt with by Special Districts under the Public Health (Scotland) Act, 1897. This was needed because the village had suffered from occurrences of typhoid and scarlet fever. The public office was at the railway station until 1917 when it moved to one of the shops near the corner of High Street and Station Road. Parish Councils were abolished in 1929 and the office was then used by the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages. The provision of an ambulance wagon fell outside the Parish Council’s remit and so a number of local people organised a subscription which resulted in June 1900 in the purchase of a horse-drawn ambulance built by Fleming & Taylor in Airdrie. By agreement with the proprietor, Mr Norval, it was kept at the Crown Inn to be sent out in emergencies. It was replaced by a Ford motor ambulance in 1917.

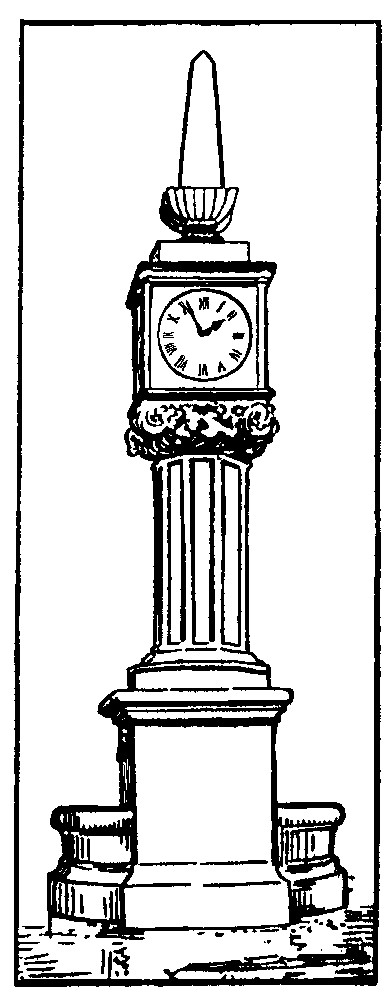

The turn of the century saw a small number of local men go off to serve in the army in South Africa. One of those that did not return was the only son of the laird of Balquhatstone House and this resulted in the erection of a monumental clock at the Cross. It stands 35 feet tall and was unveiled in July 1902. Designed by the well-known architect George Washington Browne of Edinburgh, the ornate pillar was sculpted by Hayes of Edinburgh to carry a handsome clock by Barrie of Edinburgh. At its base are two drinking fountains with horse troughs, and inscribed on the front is the inscription:

“Erected by the tenantry and inhabitants of Slamannan and neighbourhood in memory of the patriotic devotion of George Peddie Waddell, only son of Mr and Mrs Peddie Waddell of Balquhatstone, who volunteered for active service in South Africa with the Lothians and Berwickshire Imperial Yeomanry, and after the hardships of a year’s campaign, died at Germiston, Transvaal, on 8th February, 1901, aged 26 years. Amiable, generous, esteemed by all, he freely gave his service and life in the cause of the country that he loved.”

At the time that the memorial was unveiled the drinking basins were dry and it was only in the following year, when water pipes were installed in the village, that it was connected to the Falkirk mains supplied from the Buckie Burn in the Denny Hills. The 14ins pipes were laid by a contractor for the County Council and were completed in May 1903.

The completion of the water mains meant that due consideration could be given to a proper drainage system and to the provision of firefighting equipment. In 1911 the County Council provided 750ft of hosepipes, a stand pipe and nozzles for firefighting. These were stored in Gillespie’s shop in the Main Street ready for use. It was only the advent of the Second World War that led to the establishment of a fire station in the village as part of the Auxiliary Fire Service.

Although Balquhatstone and Lodge Collieries closed in the 1890s, some of the mines were able to carry on exploiting new seams and extending outwards. The glory days were certainly gone and in 1910 one of Slamannan’s poets, William White, wrote:

Pair auld Slamannan, deserted alane,

The flower of thy youth is high faded and gane;

Thy chimneys are smokeless, thy hammers are still,

Thy once busy pathways grim silence doth fill.

The wee birds sing merrily there wi’ their brood,

Where alas! busy workshops in other days stood,

An' aye as they chant ilka note seems a tale

O! the glorious past days of “Auld Cullochvale".

During the Great War many of the young men served abroad with the armed services and a large number did not return. 52 of these are named on the war memorial built on the corner of Station Road and Avonbridge Road and unveiled on 15 October 1921 in the presence of nearly 3,000 people

Next to the war memorial, in the Smithy Field, a Miners’ Welfare hall was opened on 11 December 1925. The capital for its construction was provided by the Miners’ Welfare Fund under the Mining Industry Act of 1920 which placed a tax of 1d on each ton of coal. The Slamannan miners then contributed a weekly sum from their wages to pay for its maintenance. It held a reading room and a games room and was open to all. Here political speeches were made and the public entertained.

Few of the coalmasters retained their dwellings in Slamannan and in March 1921 Binniehill House was bought by a group of Jews for use as a Rest Home for members of their faith in failing health. The Jewish Convalescent Home was formally opened on 21 May 1922 with accommodation for 30 residents. It remained open until 1932.

For many years there had been talk about introducing electricity into the village but it was 1914 before the Parish Council was able to arrange a supply from the Bonnybridge Electric Power Company. Street lighting, however, remained illuminated by gas. Not until 1919 did the first tarmac roads appear in the village. After the First World War there was a crisis in housing in the Slamannan area. The miners’ rows in the vicinity had been built as cheaply as possible with only a short design life and they were becoming uninhabitable. Stirling County Council had been condemning many of them as unfit for human habitation and so the owners simply demolished them. The County Council allocated twelve of its new houses to be built on the south side of the main road at Blinkbonny and Brownrigg. Seven blocks of four apartments each were completed for 28 families and form a distinctive row facing Blinkbonny Park.

The first full time motor bus service from Slamannan Station to Falkirk was begun on 10 April 1924 by Wilson Marshall & Sons and went under the name of “Venture.” Before long the company also started services to Airdrie and Bathgate. The bus station built by the company as the Falkirk terminus in Cow Wynd in 1928 is still there, used as shops.

Although proposals for sewers were put forward from time to time, it was 1932 before the village got an integrated system of drainage and a new treatment plant to the north of Balmulzier Road. In 1931 the gas lamp standards in the streets were finally taken down and replaced with electric ones.

On 2 July 1935 a meeting was held in the Slamannan Public School at which it was decided to engage a district nurse. A District Nursing Association of Slamannan, Avonbridge and Limerigg was formed and the following month Elizabeth Robson was appointed. The Association was subsequently taken over by Stirlingshire County Council and in 1956 a nurse’s house was erected next to Stratton Cottage in Bank Street.

Little other new building occurred in the village in the 1930s, the notable exception being a few bungalows on the north side of the Avonbridge Road forming part of the ribbon development.

During the Second World War Slamannan was seen to occupy a strategic position in the road network. As a consequence it was designated as one of only two nodal points in the Falkirk district – the other being Falkirk. The Home Guard was to defend the crossroads to the last bullet and the last man. Slit trenches and gun loops were placed at the various entrances to the village and a gun pit containing a spigot mortar was constructed in the garden of the house facing up Station Road (Bailey 2008). In 1942 the old Rosemount School was converted into an auxiliary fire station. The firefighting team was called out on several occasions to help the Home Guard and air raid wardens to look for unexploded ordnance and also to deal with the crashes of two Spitfires based at Grangemouth (Bailey 2006). An observation post was constructed at Hillhead to the east of the village to spot enemy aircraft. It was manned by the Observer Corps whose motto was “To be forewarned is to be forearmed.” They claimed to have seen Rudolph Hess’s aircraft before it crashed south of Glasgow on 10 May 1941. All signposts had been removed at the beginning of the war in order to confuse any enemy invasion troops, and most were never returned.

In the period between the wars 44 houses had been built by the local authority in the parish of Slamannan. Between 1945 and 1961 the number of houses built by the same agency was 348. In the village the “Scheme” was rapidly constructed. The names of its roads reflect the locality – Rashiehill Road, Drumclair Avenue, Balcastle Road, Laurence Crescent, Culloch Road, and Birnie Well Road. In 1959 Binniehill House was demolished and Gowanlee Drive took its place.

Castlehill Avenue, Balquhatstone Crescent, Southfield Drive and The Rumlie followed to the west. In 1961 there were a total of 296 privately owned houses of which 188 were owner occupied (Cameron 1961). Private building has in recent years been but little.

Elsewhere the poorly constructed buildings of the late nineteenth century were flattened to allow for modern improvements – many of which never came and so today there is a lot of grass. New Street had been built on low-lying land close to the Colloch Burn and was prone to flooding. The only remaining building there now is the Methodist Church which was converted into a house in the early 21st century. After the wholesale removal of the houses in New Street the burn was canalised (around 1980) to stop future flooding.

The south side of the Cross which had given the village centre its urban character was unfortunately redeveloped in the mid 1960s and replaced with a three-storey block with shops on the ground floor and flats above. The Bank of Scotland moved from Balcastle Villa into one of the new shops on 4 September 1968.

Shortly afterwards the villa was demolished to make way for the Community Centre. Just a little to the east of the new centre a Health Clinic was opened in 1971 on the site of the old bank. This was part of a range of services being updated at the time. In 1969 a purpose-built Fire Station was opened in New Street.

Then, in 1973 Slamannan became part of the Falkirk District and not much has happened since. Thorndene Terrace on the west side of the Main Street was built by Hanover Homes in 1981 to care for older people, and then demolished to make way for social housing. The Royal Hotel has stood empty for a number of years and in 2023 Falkirk Council proposed to demolish it. In 1984 it had been one of five licensed premises – the others being the St Laurence, the Fit O’ the Toon, the bowling club and the old Miner’s Welfare Club. There are fewer shops too. At the Cross there is a pharmacists and a public library. The Slamannan Co-operative was incorporated into the Falkirk and District Co-operative in 1966 and closed shortly afterwards. It was reincarnated as a convenience store. The bank closed at the beginning of the new millennium. Today Slamannan is a commuter settlement with John Aitken Ltd, drilling engineers, one of the few remaining businesses. The 1902 memorial clock remains in pride of place, fearlessly marking the passage of time.

Chronology – Time Line

- 1840 Slamannan Railway opens

- 1840 Curling club

- 1844 Free Church building at Pirney Lodge

- 1845 Slamannan Parochial Board

- 1847 Sub-post master

- 1851 Horse and Cattle Fair

- 1855 Gas works

- 1858 City of Glasgow Bank

- 1859 Horticultural Society

- 1860 Industrial Co-operative

- 1861 Mutual Improvement Society

- 1861 Balquhatstone Church building

- 1863 Masonic Lodge

- c1865 Total Abstinence Society

- 1874 Methodist church building

- 1879 Police station and lock-up

- 1881 Orange hall

- 1885 Gas street lights

- 1889 Lodge of the Loyal Order of Ancient Foresters

- 1894 Bowling club

- 1894 Slamannan Parish Council took over from the Parochial Board.

- 1902 Masonic Lodge building

- 1902 Piped water

- 1912 Cycling club

- 1919 First council houses

- 1921 Jewish convalescent home

- 1923 Miners’ Welfare Institute

- 1926 Tennis courts at Miner’s Institute

- 1927 County library

- 1932 Sewage works

- 1936 playing field

- 1942 Rosemount Fire Station

- 1956 Blinkbonny Park

- 1960 Cross redevelopment

- 1960 St Mary’s Chapel (closed c2001)

- 1971 Community Centre built

- 1971 Health centre opens

Sites and Monuments Records

| Clerkshall | SMR 499 | NS 8557 7323 |

| The Thackie | SMR 1436 | NS 8559 7332 |

| Slamannan Parish Church | SMR 201 | NS 8561 7339 |

| Easter Balcastle Mill | SMR 1207 | NS 8545 7267 |

| Slamannan Motte | SMR 326 | NS 856 734 |

| Slamannan Bailey | SMR 501 | NS 8561 7340 |

| Castle Hill | SMR 502 | NS 8570 7320 |

| Slamannan War Memorial | SMR 512 | NS 8565 7308 |

| Slamannan Boer War Memorial | SMR 597 | NS 8565 7308 |

| Linn Mill (Slamannan Mill) | SMR 635 | NS 9120 7227 |

| Slamannan Parish Churchyard | SMR 1079 | NS 8561 7338 |

| Slamannan Primary School | SMR 1103 | NS 8530 7300 |

| Slamannan Railway | SMR 1243 | |

| Slamannan Gas Works | SMR 1285 | NS 8553 7318 |

| St. Laurence Inn | SMR 1286 | NS8558 7311 |

| Slamannan RC Church | SMR 1408 | NS 8536 7301 |

| Slamannan Methodist Church | SMR 1413 | NS 8567 7325 |

| Slamannan Village | SMR 1417 | |

| Slamannan Auxiliary Fire Station | SMR 1600 | NS 8563 7314 |

| Slamannan Heroes Memorial | SMR 1651 | NS 8551 7308 |

| Slamannan Police Station | SMR 1743 | NS 8562 7319 |

| Slamannan Masonic Hall | SMR 1745 | NS 8557 7329 |

| Slamannan Church Hall | SMR 2327 | NS 8557 7336 |

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 2006 | Grangemouth: from Airlines to Air Cadets – the Story of the ‘Drome. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 2008 | Hard as Nails: the Home Guard in Falkirk District. |

| Cameron, A. | 1961 | The Third Statistical Account; Parish of Slamannan. |

| Hood, J. | 2015 | Old Slamannan and Avonbridge. |

| Murray, A. | 1911 | Fifty Years of Slamannan Co-operative Society Limited. |

| RCAHMS | 1963 | Stirlingshire: An inventory of the ancient monuments. (Quoted below) |

| Reid, J. | 2009 | The Place Names of Falkirk and East Stirlingshire. |

| Reid, J. | 2010 | ‘The Feudal Divisions of East Stirlingshire: Slamannan Parish,’ Calatria 26, 65-78. |

| Slamannan History Group | 1990 | Slamannan and Limerigg: Times to Remember. |

| Waugh, J. | 1977 | Slamannan Parish through the Changing Years. |

RCAHMS 1963 Stirlingshire: An inventory of the ancient monuments.

271. SLAMANNAN VILLAGE. Slamannan contains very little of architectural interest, as most of the houses are small, featureless buildings of one or two storeys dating, at earliest, from the beginning of the 19th century. Two, which show rather more character, are worthy of record. (i) Numbers 7,8, 9 and 10 High Street. These four one-storeyed dwellings have been designed as a block, the outermost two (Numbers 7 and 10) being smaller and lower than the central pair, to which they form wings, having hipped roofs which rise to abut on the gables of Numbers 8 and 9. They are built of squared rubble brought to courses, with V-jointed dressings at voids and quoins. The gables have plain tabling and cavetto moulded skewputs. The chimneys are ornate. (ii) An unnumbered house in Main Street, formerly the schoolhouse. This has now been subdivided into two flats, and has an outside stair of bright, but was originally a single dwelling with an inside stair. It measures 34ft. 7in. by 18ft.9in. externally; on the ground floor there is a central door with a window, now enlarged, on either side of it, and on the first floor three windows, symmetrically arranged. The door has a lintel bearing the date and initials 17DAMS76 divided by a false keystone. The masonry is random rubble with dressed stones at quoins and voids; there is a moulded eaves-course, and the gables show plain tabling with a large roll skewput at each corner. 8573 NS 87 SE 20th March 1953