When the D.C.L. Company acquired Bo’ness Distillery from James Calder & Co, the field to the south, which at one time was cultivated, was retained by Sir James Calder, who in 1923 offered it to Bo’ness Town Council for recreation purposes. One controversial condition was that Sunday games should be permitted – very unusual in Scotland at the time. Bo’ness Town Council had a mind but not the courage to turn down the offer. One weighty privilege in the deed of gift was to give off a strip of ground facing the public road to build workmen’s houses – the income from the feus serving to pay for the upkeep of the park. So, the Town council arranged a public poll which rejected Sunday games and, despite the low turnout, James Calder removed the condition. In any case, it was rather an irrelevant point as the football pitch in Castleloan Park, which lay adjacent and to the west side, was available for use on Sundays.

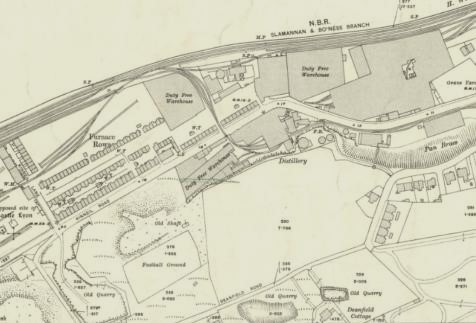

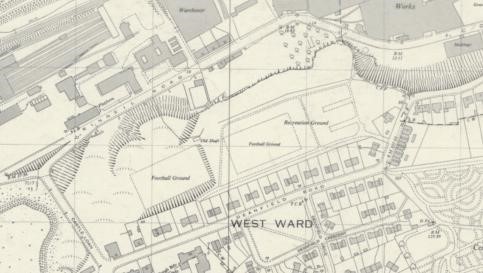

Castleloan Park had been a piece of waste ground where the refuse from the Store Pit was dumped. The local footballers were desperate for a football pitch and approached the Duke of Hamilton’s factor with a request for land. They came to an agreement that if the football club levelled the ground it would be handed over to them, but might be repossessed if the Kinneil Colliery required it for its development. The local youths set to work. They got the use of a horse and cart gratis from Hugh Johnston, as well as hutches and rails from Kinneil Colliery, and over a period of about six hard months levelled the park. No title deeds were exchanged and by an oversight the ground was included in a deal between the Duke of Hamilton and Bo’ness Town Council over the purchase of the slob lands.

Calder Park extended to just over five acres and the Town Council widened the road and built 48 houses in front. Sir James Calder gave £350 towards laying out the park. The girls’ section of the playground had two sets of three swings, a giant stride, and a see-saw; the boys’ section had two sets of swings, a joy-wheel, and a see-saw. The swing bases were laid with tar macadam and finished with tar slags. A proposal to erect a bandstand was dropped. 20 seats were put in, trees planted on the north and south sides, and shrubs on the east. Walks were formed and a 12ft wide road constructed along the south side from gate to gate. A football pitch was laid out at the west end, and the whole area fenced about. It was officially opened in July 1927.

Considerable controversy occurred in 1935 when the Town Council decided to build a large number of houses on both Calder and Castleloan Parks, completely filling them. The residents in the area lodged protests. It was pointed out that elsewhere Scottish burghs were building new housing around parks using them as a feature, and not on the parks. It was also noted that those parks near to the homes of the councillors were not to be built over. The Council pressed ahead with its plans, determined to steamroller the project through. Architects’ plans were drawn up and services were led to the fields. The opinion of the councillors was that all that was required to use the ground for house building was the permission of the donor of the park and the Duke of Hamilton’s Trustees – and those permissions had already been given.

The footballers were livid and wrote to Sir James Calder and the Duke of Hamilton. Sir James was shocked as he had been given to understand that the new housing would be on the margin of the park and would not interfere with its function as a recreational area. He withdrew his permission. The Duke of Hamilton also intimated his concern. Against such determined opposition the scheme was eventually dropped and at the next election the councillors who had wasted so much time and money were ousted.

Grid Reference

NS 990 812