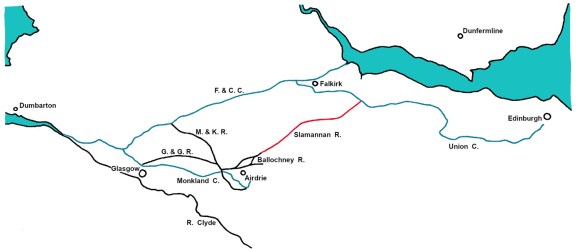

The reasons for advocating the creation of the Slamannan Railway in 1835 are not hard to find. The railways operating in North Lanarkshire at that time were notably profitable – the Ballochney Railway, for example, paid a dividend of 5% in 1834-5. The Monklands were rich in deposits of coal and ironstone, but due to the lack of convenient transport these mineral resources had remained largely unexploited until the closing years of the eighteenth century. With the opening of the Monkland Canal and, later a comprehensive network of railways, industrial development in the vicinity of Coatbridge proceeded at a startling pace. In the 1820s and early 1830s there was a tendency for the working of minerals to expand north-eastwards, and collieries were opened at Rayards, Ballochney, Whiterigg and Stanrigg, all to the north-east of Airdrie. Several ironstone pits were also established, and this district was served by the Ballochney Railway which opened in 1828, connecting with the existing Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway at Kipps. The Slamannan promoters hoped to encourage the further continuation of this expansion north-eastwards, and they were confident that the coal fields extended for several miles in that direction.

G. & G.R. – Garnkirk and Glasgow Railway;

M. & K.R. – Monklands and Kirkintilloch Railway;

F. & C.C. – Forth and Clyde Canal.

For the purposes of the act, it was stated that the railway would be:

“of great local and public utility, by opening an easy and cheap means for the conveyance of coal, lime and manure in the neighbourhood of such railway, and of coal and ironstone, and other minerals, to the said canal, from where they may be carried to Edinburgh and other parts, and also to the said Ballochney Railway, by means of which, and the subjacent railways and canals, they may be carried to Glasgow and other parts.”

The promoters hired the civil engineer John Macneill to provide information on the area and to delineate a route for the railway. They then issued a document to prospective shareholders in October 1835 (a copy may be found at SRO GD1/579/25). In this they made it clear that the principal trade on the new railway was initially expected to be the conveyance of Monkland coal to Causewayend for transportation thence by the Union Canal to Edinburgh and the East of Scotland markets. At that time Monklands coal for Edinburgh went by the Ballochney Railway to the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railways, to the Forth and Clyde Canal, and then to the Union Canal, a route of about 60 miles involving the negotiation of fifteen canal locks. The prospectus pointed out that the route by way of the proposed Slamannan Railway and the Union Canal would be only 35 miles in length and would involve no canal lock negotiation. It was estimated that the saving on carriage expense for Whiterigg and Stanrigg coal going to Edinburgh would amount to 2/- per ton. Attention was also drawn to the extensive nature of the mineral fields through which the new railway was to pass, and confidence was expressed that “a great number of blast furnaces would be erected on the line of the new railway.” A purely local passenger service was proposed between Airdrie and Causewayend, it being expected that:

“all parties from Airdrie and the populous districts of Lanarkshire adjacent to Airdrie would take this route to Edinburgh, Falkirk, Linlithgow, and to Fife, and the North of Scotland.”

Although the use of locomotives was authorised by the Slamannan Act, the intention was expressed in the prospectus to use only horses for the motive power, thereby enabling a saving in the maintenance expense of the track. It was confidently predicted that the total expense of construction would be considerably under £60,000, and that when the railway was in operation the free annual revenue would be £5,750, enabling a dividend of 10 per cent.

Almost incidentally, it was pointed out that the railway would be of great use to the farming communities adjoining the railway. Macneill observed that:

“along great portions of it, there are no cart roads, and in some places the farmers are obliged to carry the produce of their farms on horses’ back to the nearest parish road where carts can be had…”

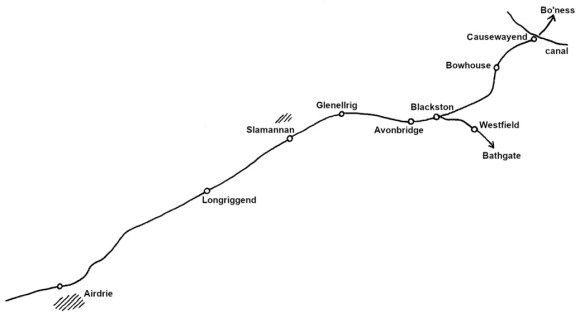

The Slamannan Railway Act – “to make and maintain a Railway from Stanrig and Arbuckle, in the county of Lanark, to the Union Canal at Causewayend, in the county of Stirling,” – became law on 3 July 1835. The Act was for a line which covered a distance of 12½ miles and by terminating it at Causewayend it avoided the need to cross the lower valley of the River Avon. The authorised share capital was £86,000 and in addition there were powers to borrow £20,000. The act of incorporation stipulated that the sum of £65,769 should be subscribed before any of the powers of the Act could be put into force. Nine directors were appointed, one of whom was Robert Ralston of Glenellrig near Avonbridge. The proprietors had presented the Bill to Parliament with the minimum of publicity, and no subscription list had been prepared. Thomas Grahame had said that “The scheme is so obviously advantageous that the subscriptions would be easily filled up.” This task was now put in hand.

The Company of Proprietors was duly constituted on 15 April 1836 and a committee elected to manage the company’s affairs. John Macneill set about making a detailed report which could be used as the basis for the award of contracts to the construction firms. The line was divided into five lots, each to be awarded separately. Lot 1 was in the east, commencing where the Ballochney Railway ended. It contained difficult terrain in the shape of a moss and it was realised that the consolidation process necessary for the formation of the railway would take time and consequently it was the first to be advertised:

“SLAMANNAN RAILWAY. ESTIMATES WANTED FROM EARTH-WORK CONTRACTORS AND BUILDERS. THE SLAMANNAN RAILWAY COMPANY are ready to receive TENDERS for Executing the FIRST LOT of their RAILWAY.

This Lot commences at the eastern extremity of the Ballochney Railway, in the parish of New Monkland and County of Lanark, and terminated upon the Lands of Lodge, in the parish of Slamannan and County of Stirling, being a distance of nearly 3½ miles.

The Lot includes, besides the cutting of about 125,417 cubic yards, nearly one half of which is moss, and the embanking of about 36,763 cubic yards, the erection of one road bridge and two farm occupation bridges, the ballasting and boxing of the roadway, and the laying of the rails, together with the feuing in of the Railway grounds.

The Line of Railway has been staked off, so that it may be seen by intending offerers, to whom the working plans and specifications of the lot will be submitted, at the office of Messrs Mitchell, Grahame, and Mitchell, No 36 Miller Street, Glasgow, until Thursday the 30th day of June current, until which day, sealed tenders for executing the work may be left at that office.”

(Scotsman 4 June 1836, 1).

On the same day the office of resident engineer was sought.

“SUPERINTENDENT OF RAILWAY WANTED. THE SLAMANNAN RAILWAY COMPANY being about to commence the formation of the SLAMANNAN RAILWAY, wish to receive applications by qualified persons, who may be willing to fulfil the office of RESIDENT ENGINEER when the work is being executed, and of a SUPERINTENDENT after the Railway is opened for trade.

The Railway extends for about 12½ miles from the east extremity of the Ballochney Railway, in the parish of New Monkland, and County of Lanark, to the Edinburgh and Glasgow Union Canal at Causewayend, in the parish of Muiravonside and County of Stirling.

The applicant must be acquainted with Earthwork and Masonry, and the other operations required in forming and working a Railway, and with making and upholding bridges, fences, and other works therewith connected, and must produce satisfactory testimonials of his talents and character. It will be an additional recommendation that he is acquainted with the practice of a Surveyor in making plans and taking sections, and with the construction of locomotive Engines.

A Salary of £150 a year, with a free house, will be given to a person duly qualified and preferred to the situation.

Farther particulars may be learned by application to John Macneill Esq, Civil Engineer, 7 St Martin’s Place, London…”

(Scotsman 4 June 1836, 1).

The resident engineer would oversee the day to day working of the contractors and the ordering of rails and rolling stock. Thomas Telford Mitchell was appointed resident engineer. He had served in that capacity with the Newtyle and Coupar Railway for two years, and was to spend eight years on the Slamannan Railway. On 12 November 1836 a second call of 10% was made on the capital stock, payable by 21 December.

The Slamannan Railway was Macneill’s first major work in Scotland and occurred at a time when the design of railways was being transformed. He seems to have been an advocate for the use of locomotives. He reported to the committee of management that the nearby Wishaw and Coltness Railway had experienced difficulties with horse haulage by independent operators, referring to:

“the great confusion which always takes place on railways where a great number of horses are employed by persons of different interests“.

Prompted by Macneill, the thoughts of the Committee turned to locomotive haulage and the construction that was to follow reflected this.

In October 1836 the first contract was placed with John Marshall of Glasgow for the construction of the western portion of the line (Lots 1 & 2 being 5¾ miles) at a price of £17,851.18.4. It was stipulated that these lots were to be finished by 1 January 1839. The contracts for Lots 3 to 5 were advertised in April 1837. Lots 3 and 4 were considered to be relatively straight forward and so were conjoined. Lot 5 contained a major cutting and extensive embankments and was kept separate. They were soon placed with Michael Fox of Edinburgh. The total cost of these sections was to be £39,179, and they were to be finished by 1st May 1839. It was therefore hoped that the railway would be completed and ready for traffic by May 1839.

| :ot | Location | Miles | Contractor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Stanrig – Lodge | 3.5 | Arden Moss | John Marshall |

| II | Lodge – Pirney Lodge | 2 | John Marshall | |

| III & IV | Pirney Lodge – Broadhead | 5 | 7 road bridges, river bridge, several occupation bridges, culverts | Michael Fox |

| V | Broadhead Rd – Causewayend | 5 | 6 road bridges, culverts | Michael Fox |

The construction of the Slamannan Railway occurred at a time when railways were beginning to take off in a major way and it was seen as an exemplar. Macneill, always a good self-publicised, contributed a chapter to an important and influential volume of “Railway Practice” edited by S.C. Brees and published in 1838. This was a redacted copy of the contracts for Lots 1 and 2. It provided details of the cuttings, embankments, bridges, culverts, and so on. It neatly illustrates the up to date nature of the work and the state of the art. Plate 66, for example, shows an occupation bridge on a farm road on the lands of Hill. The bridge was of trussed girders instead of a stone arch. This was unusual at the time but much more economical.

More common was the use of stone blocks instead of wooden sleepers to hold the rails. The specifications state that:

“The blocks to be provided for this work, are to be taken from Craig Mochan, or Avon Bridge, or such quarries as may be approved of by the Inspector. To be not less than 9 inches thick, 18 inches square on the top, and 20 inches on the sole; those at the joining to be 20 inches thick 20 inches square at the top, and 24 inches on the sole. To be free from cracks or fissures, and otherwise neatly hammer dressed to the shape of the drawing, with the top, and bottom quite parallel, and so that every block shall rest on the natural bed of the stone. Two holes are to be bored in each block, 5 inches deep, and 1½ inch in diameter. The blocks to be placed as hereafter described, through the cuttings and embankments on the solid ground... As it is of the greatest consequence that the Blocks should be provided and dressed in the quarry as early as possible, so as to be examined by the Resident Engineer from time to time, previous to their being carried to the work, by which means he has time to examine and reject those that are defective in size or quality…”

The illustrations show the blocks placed diagonally to the rails – as lozenges rather than squares. One account mentions the dressing and boring of 2,008 Railway Blacks in Ellrig Quarry (Herapath’s Railway Journal 28 March 1840, 3).

Heavy stone blocks could not be used on soft ground and the Specification notes that :

“Through the Moss, sleepers are to be used; they are to be of fir, or elm, that would square to 8 inches, and be 9 feet long, and 4 inches deep, and 10 inches broad…”

Newspaper adverts were placed for these in October :

1837:“SLAMANNAN RAILWAY. TO TIMBER MERCHANTS. OFFERS are Wanted for Furnishing 3000, or any less quantity, of SCOTS FIR, or LARCH SLEEPERS, to be laid down upon the Banks of the Forth and Clyde Canal at Kirkintilloch, of the following dimensions: Every two Sleepers to consist of a Tree, 9 feet long, and 12 inches diameter at the small end, sawn up the middle…”

(Perthshire Advertiser 19 October 1837, 1).

In February 1838 it was reported to the annual general meeting of the proprietors that J. Marshall had “not made such progress as he ought to have done,” and shortly afterwards he had the westernmost two miles of the line removed from his contract. £1,497 was deducted from the contract price, and the Slamannan Railway’s own engineer, T.T. Mitchell, assumed charge of the construction of this section. Marshall does not seem to have been blamed for his failure as it was found that in at least one place the moss was 30ft deep. Rather than simply use wooden sleepers in the conventional manner if was found that platforms of timber laid under the rails were necessary.

Pilfering and vandalism had become a hallmark of large construction projects and the Slamannan Railway Company was quick in hiring its own police force. One of the men taken on was Peter Crawford who became one of Falkirk town’s best known constables, affectionately known as Lang Pete (Meek 2003). The problem was not just the local population but also the large numbers of labourers employed in the project. This is demonstrated by a report of a riot in August 1838:

“RIOT – On Sabbath last, the Falkirk Sheriff and Procurator-Fiscal, with the criminal officers, were sent for express to the village of Maddiestown, where it seems the Irish labourers employed at the Slamannan Railway, who have of late committed extensive and alarming outrages on persons and property, had, after their pay on the previous day, assembled in a formidable body, and were setting all at defiance. A great number of special constables turned out to aid the authorities, but the resolute exertions of the numerous colliers in that quarter mainly contributed to overawe the lawless mob. One of the number only was taken into custody, charged with an aggravated assault, & c. he was summarily tried next day, and sentenced to thirty days imprisonment,

(Sun (London) 6 August 1838, 3).

There is a story that the Irish navvies working on the Slamannan Railway tried to buy alcohol at Woodside Toll near Torphichen, but the toll-keeper was afraid to supply them with yet more. The Irishmen were much annoyed and smashed every window in the place and would have wrecked the tollhouse had it not been sturdily built of stone. The people of Torphichen had to be called out to quell the rioters and the navvies had to be fired upon before they would retreat. One of them, it is said, had to go about with a bullet in a portion of his anatomy for a good long time afterwards (Linlithgow Gazette 13 June 1902, 8).

The Irishmen were mostly Roman Catholics and the nearest place for worship was Falkirk. An attempt was made to get them a nearer place of meeting, but the navvies were too unsettled, and it was sometime later that a large unused currying loft in Linlithgow was made available (Linlithgow Gazette 26 December 1891, 3). As new collieries opened up, more Irish settled in the area to the south of Slamannan and a chapel was built near Limerigg.

Working conditions were far from ideal and inevitably accidents happened. The mode of excavating deep cuttings was to dig a large trench down the centre and then to extend it to either side with vertical faces. These faces were then allowed to collapse and the loose earth was taken out. The dangers associated with this working method were obvious to all but they were considered acceptable. In January 1839 while some of the workmen were engaged undermining the earth near the east end of the line, it suddenly gave way and buried two of the men under it. They were immediately dug out, but although medical aid was almost instantly procured, one of them expired at the time, and the other only survived about an hour (Scotsman 30 January 1839, 2).

The best way of building an embankment, especially in clay, was to form the bank in shallow layers, between 2 and 4 ft thick, each running out to the full length, and compacted it with ‘beetles’ before the next layer was added. The bank was thus progressively raised and there was time for some consolidation in the bank and foundation. This was the method (with 4 ft layers) specified by John Macneill in 1836 for the embankments on the Slamannan Railway where the strata chiefly consisted of Boulder Clay overlying Coal Measures and the total excavation amounted only to 1 million cubic yards. The largest embankment was 40 ft high with 2:l slopes and 180,000 cubic yards of fill. This mode of construction was slow and so many railways adopted the method of running out the bank to its full height at once by end-tipping from the advancing head of the bank on a level with the bottom of the cutting. This was well suited to the combined operations of cutting and embanking on a large scale but was not adopted for Slamannan (Skempton 1996).

The stone bridges, culverts and retaining walls on the Slamannan Railway are amongst the finest in Scotland. John Macneill was impressed and in his annual report in 1840 stated that:

“The masonry executed by Mr Fox is, in every respect, done in a most satisfactory manner, and it is but justice to say that in this, as well as in every other department, he has shown much anxiety to conform to his contract; and this, I doubt not, the Company will hereafter feel the advantage of in regard to the maintenance of the railway.”

His specifications had been rather precise. Here, for example is that provided for the culvert to take the Culloch Burn at Binniehill:

“An arch, 9 feet span, is to be built over the Cullogh Burn, under a 35 feet embankment, according to figures 1, 2, and 3, on Plan No 8. The ground is to be opened for the foundation in the direction of the stream; it is to be sunk 6 feet below the ground line, or an much more as may be necessary to secure a sure and firm bottom. The foundations of the abutments and wings to be of sound rubble masonry; xx feet thick at the base, to have an off xx of xx at xx height, and 9 feet thick within xx feet of the ground line. The abutments to be of sound rubble, hammer dressed on the face, and no course to be less than 8 inches thick,

All the stones required for the blocks, stone dykes, and bridges had to be provided by the contractor and the quarries at Craig Mochan, Arden and Avonbridge were approved. Stone from other sources had to be checked by the resident engineer or inspector before use. One clause in the contract read:

“Should stone be found in the cuttings, or along the line, fit for blocks or bridges, a corresponding deduction is to be made from the lump price mentioned for the same, as the Company’s engineer shall consider fair and reasonable between the parties.”

“and to be of the same thickness throughout. None of the arch stones to be less than 18 inches long, nor less than 12 inches deep, and their beds neatly dressed to radiate to the arch. The arch to be 9 feet span, to rise 3 feet, and to spring xx feet above the ground line. The xx to be hard sound stone, 9 inches deep, laid dry, and firmly packed. The wing walls to be xx feet long, to be founded as low as the abutments, if found necessary, and to be built of sound stone masonry, xx feet thick and xx at the ground line. The spandrel and wing walls, from the level of the ground, to be xx feet thick, the counterforts to rise to the level of the springing. The parapet and wing walls to be coped with stone, similar to the bridges already described.”

The names of the individual masons may not be known but we can be sure from the following advert that they were not members of a trade union:

“SLAMANNAN RAILWAY: MASONS WANTED. A NUMBER of STEADY MASONS will find employment upon the SLAMANNAN RAILWAY during the season, and to whom liberal encouragement will be given. From the annoyance experienced at this work during the past season, arising from combination, no Mason belonging to the Trade’s Union need apply.”

(Scotsman 24 January 1838, 1).

All of this cost money. At the next annual general meeting of the Slamannan Railway Company in February 1839 the shareholders were informed that both contractors had failed to fulfil their engagements in the stipulated time, and grave dissatisfaction was expressed about their rate of progress. At the same meeting it was reported that almost the whole of the subscribed capital had been spent. Of the authorised capital of £86,000, only £67,150 had actually been created into stock, and the total cumulated expenditure of the company at 31 December 1838 was £67,072.13.7. Apart from paying contractors and buying land, the money had been spent in a wide variety of ways. In 1838, for example, £8,222.13.7 was spent on rails, chairs, iron spikes and felt pads. In July 1839 authority was obtained by an Act of Parliament to increase the share capital to £140,000. This Act also gave powers to borrow money up to one third of the value of the capital stock. By March 1840 cash credit of £20,000 had been negotiated with the Royal Bank of Scotland; and 538 shares of New Stock had been created, of which 536 were allocated to the original proprietors.

Sections of the single line of track of 4ft 6ins gauge had been laid, and space was left to double track at a future date if traffic justified it. The rails weighed 50 lbs to the yard and were manufactured by Guest & Co of Dowlais, South Wales. The chairs were supplied by Murdoch, Aitken & Co of Glasgow, and their sockets corresponded exactly with the cross section of the rail so that no keys were necessary.

The construction process had been painful. The company suffered during construction from ‘considerable difficulty‘ in obtaining land, procrastinating contractors, high material costs, and problems of money-raising in the deepening depression of the late 1830s. By the end of 1839 the western part of the line was almost finished. The main difficulty had been the subsidence in the Arden Moss near the junction with the Ballochney Railway. Since January that year four men had been kept in attendance to make up the subsidence which occurred there from time to time and it was expected that this attention would be necessary for some time to come. Partly due to his extra work on this section Thomas Mitchell’s monthly salary of £12.10.0 was increased in October 1839 to £16.13.4, backdated to 1 August 1838.

The construction sites acted as magnets to children who used them as playgrounds once the workmen left, or indeed whilst wagons were being operated on those stretches of the line where the rails had been laid. It was not just the boys. One day in mid February 1840 three sisters were walking home along the line from their school in Avonbridge and came up to two wagons going along the road. The two younger got into one of the wagons for a ride. The older girl kept walking between the two wagons. She fell and the wheels went over her head, killing her instantly (Caledonian Mercury 22 February 1840, 3).

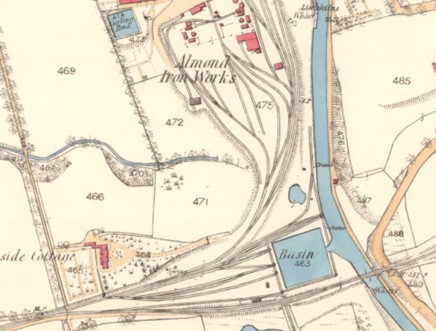

The principal operation that was still well short of completion was the excavation of a cutting near Bowhouse on the eastern part of the line. At the end of January 1840, 20,000 cubic yards of earth still remained to be excavated from it. T.T. Mitchell, however, reported that he was generally well satisfied with the work carried out by Michael Fox on this section. Attention was now turned to the finishing touches related to the operation of the railway. The first of these measures was the formation of a basin and wharfs at Causewayend, where the railway was to terminate on the Union Canal. In 1839 Macneill provided the design of a basin

“of such size and structure as to furnish adequate accommodation for the mineral traffic and for passengers, quite distinct from each other, and convenient for each.”

The Union Canal Company executed, at its own expense, that part of the works bordering upon the canal and agreed that its use would be free of wharfage or other claim to the passenger trade. The remainder of the works were contracted out to Michael Fox at a cost of £809, to be completed by 1 April 1940. The basin is still in use and measures 150ft square with a 15ft wide opening onto the canal. The south-west side of the basin is formed by a quay of massive stonework, its coping bearing some remains of loading machinery.

In June 1854 Russel & Co obtained a feu from Forbes of Callendar at Causewayend for erecting an ironworks.

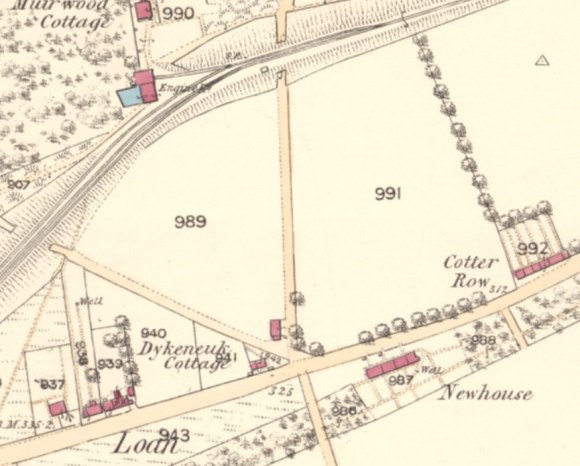

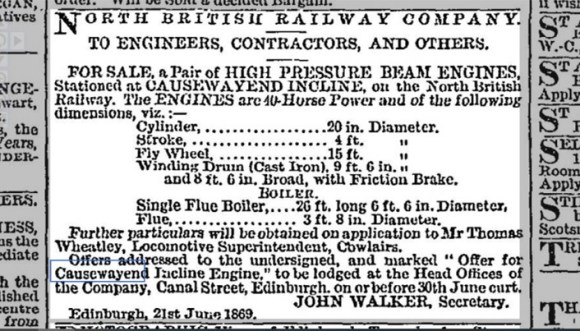

The next measure of preparation was the erection of a fixed engine and apparatus for overcoming the 1 in 22 (or 250 feet in the mile) inclination upon the railway a little way to the west of Causewayend. Following the advice of the principal and resident engineers it was decided to provide a double engine at Muirhead at the top of the slope. One engine, a boiler-house, sheds and apparatus were put out to tender with a completion date of 1 May 1840. The second engine was to be bought once the trade was sufficient.

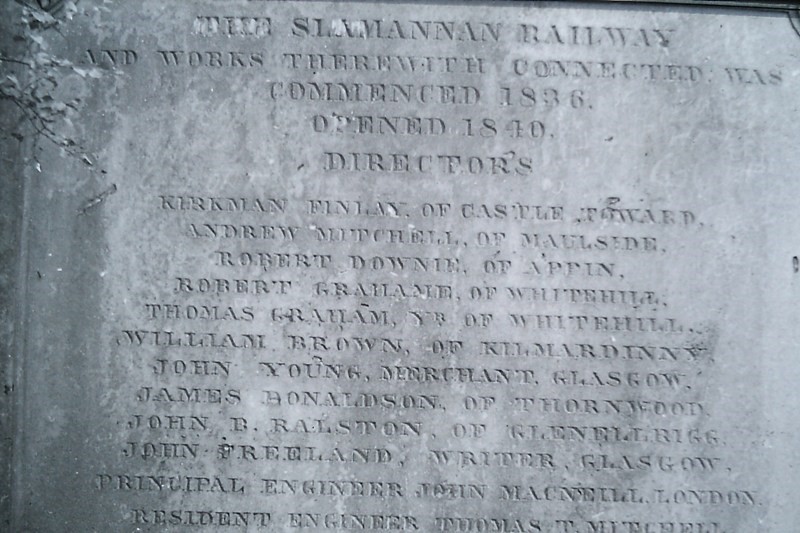

The 50 horse-power stationary beam engine was supplied by Murdoch, Aitken & Co for £1,075, with pulleys and bolts and extra work connected with the engine the total sum came to about £1,320. The incline rope was supplied by Thomas Nicholson of Dundee, and together with a cask of patent oil cost £113.17.3. The winding-engine building was composed of a very hard polished stone (a photograph of it appears in Railway News 3 June 1911, 14), and a large stone tablet was placed on the front bearing the following inscription:

THE SLAMANNAN RAILWAY,

And works connected therewith, was

Commenced 1836,

Opened 1840,

DIRECTORS.

Kirkman Finlay, of Castle Toward,

Andrew Mitchell, of Mailside,

Robert Downie, of Appin,

Robert Grahame, of Whitehill,

William Brown, of Kilmardinny,

John Young, Merchant, Glasgow,

James Donaldson, of Thornwood,

John B. Ralston, of Glenelrigg,

John Freeland, Writer, Glasgow,

Principal Engineer – John Macneill, London,

Resident Engineer – Thomas T. Mitchell.

In September 1839 the principal and resident engineers of the nearby Wishaw & Coltness Railway submitted a report to their committee of management in which they strongly recommended that locomotive power should be introduced on that railway. They made reference to :

“the great confusion which always takes place on railways where a great number of horses are employed by persons of different interests,” and to “the collisions which are daily taking place between the drivers.”

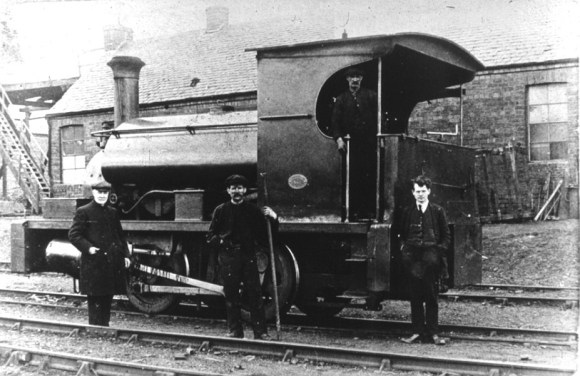

The principal engineer for that railway was also John Macneill. He was a keen advocate for the use of locomotives and his designs for the structures on the Slamannan Railway and his choice of heavy rails suggest that he always had them in mind for that line also. The tide of progress now favoured the abandonment of the idea of using only horses for motive power. In their report to the annual general meeting held on 6 February 1840 the Slamannan Railway announced that it had ordered one 4-wheeled and one 6-wheeled locomotive for delivery by the beginning of July. Out of a variety of bids which they received, they preferred one for furnishing each with its tender and a spare set of wheels. The locomotives were built by Rowan & Co at the Atlas Works in Glasgow and were named “Boanerges” and “Borealis” (sons of thunder). They were the first of many locomotives to be made there.

In the annual report the idea of a Glasgow-Edinburgh passenger service is also mentioned –

“The Glasgow & Garnkirk Railway has recently been laid with heavy rails, and is in good order; so that there is every prospect of a free, safe, speedy, and most agreeably varied thoroughfare being forthwith opened up along the whole country pervaded by these railways, and extending from Glasgow on the one hand, to Edinburgh on the other.”

All twenty bridges on the Slamannan Railway had been completed. The end was in sight and at the annual general meeting the shareholders were told:

“The railway is almost entirely laid or formed from end to end, and that the parts which remain unformed occur at three points – two of them where deep cuttings are necessary, and one where the moss has suffered depression, and has not yet been consolidated. The larger excavation occurs near the east end, on part of the lots undertaken by Mr Fox, who, during the greater part of last summer, applied a force night and day, and is still continuing his exertions energetically; and the resident engineer has been engaged in making up the depression upon the moss, and expects to secure its consolidation whenever the weather becomes dry. For the completion of these works your committee have been unremittingly anxious. So soon as the western half of the railway, which was let off to Marshall, is finished, the Ballochney Railway Company are to run a passenger carriage along it, which will open an intercourse, by means of the railway, with that part of the country, and produce an immediate return both from mineral and passengers.”

(Herapath’s Railway Journal 28 March 1840, 3).

There were some minor setbacks – the embankment at Lodge Farm subsided and so earth was procured from an adjoining field and used to dress it; the embankment at Binniehill had been deliberately left unfinished so that it could consolidate and it was decided to change the course of the Culloch Burn so that the foot of the slope could be extended on the north side. However, by the end of June the entire track had been laid and the following announcement was made in the Scotsman newspaper of 27 June 1840:

“NOTICE TO COAL AND IRON MASTERS, DEALERS IN COAL, GRAIN, &c, &c. THE SLAMANNAN RAILWAY is OPEN for TRADE from END to END, and by it, and the connecting Railways, and the Edinburgh and Glasgow Union Canal, a Speedy and Cheap Means of Conveyance is afforded between the Cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh, Airdrie, and the other Towns and Places on the Line of the Railway. Copies of the Table of Rates and Dues may be had at the Company’s Office, at Causewayend, near Linlithgow; at the Toll-house on the Ballochney Railway; or at 36 Miller Street.

By order of the Directors,

JAMES MITCHELL, Clerk.”

The railway could start earning revenue to cover its upkeep and maintenance. The stretch which initially gave most concern was at Arden Moss where the line literally floated on top of the moss. A contemporary account mentions that this arrangement had a very alarming appearance:

“the engine and carriages, as they went along, causing a deflection of the platforms or rafts, of from 2 to 3 feet, which gradually rose to their proper level behind the train, exactly like a sluggish wave, as soon as the whole had passed over”

(Fullarton 1842, Vol 2, 676).

The official opening of the Glasgow-Edinburgh passenger route took place on 30 July 1840. The following account appeared in The Glasgow Herald of 3 August:

“On Thursday last the Directors of the Slamannan Railway along with a number of shareholders, some of the Directors of the Union Canal, and several practical engineers, took an excursion along the Glasgow and Garnkirk, the Monkland and Kirkintilloch, the Ballochney and Slamannan Railways to Causewayend near Linlithgow, on the Union Canal, and thence by the Union Canal to Edinburgh. The party left Glasgow at five minutes past 8 o’clock in the morning, and reached Causewayend at 20 minutes before 10. By one of the swift passage boats the party were conveyed to Edinburgh in two hours and a half – the whole journey from Glasgow to Edinburgh being thus performed in four hours with the utmost ease and pleasure. After partaking of an elegant refreshment, provided, in the most handsome manner, by the Directors of the Union Canal Company, the party returned to Glasgow in time for dinner. We understand that this route to and from Edinburgh will be opened to the public this week, when a speedy, safe, agreeable, and cheap communication with the metropolis, will be opened up to our fellow citizens.”

That inter-city passenger service opened to the public on 5 August. The route through Slamannan now became the principal means of travel between the two great cities, involving a canal boat trip, the transit of three rope-worked inclines over four railway companies, and a railway running on stone block sleepers and, west of Arbuckle, finding a path among horse-drawn coal trains. At first there was only one service each way daily. In the eastbound direction the train left the Garnkirk & Glasgow terminus at Townhead in Glasgow at 10.15am, and in the westbound direction the canal boat left Port Hopetoun in Edinburgh at 7am. The single fares were 7/6 (First Class and Cabin of boat) and 5/- (Second Class and Steerage). By the beginning of October, a second connection each way was advertised. The eastbound train left Townhead at 2.30pm and in the westbound direction the canal boat left Port Hopetoun at 11.30am. The new services were advertised as “mixed trains, in about five hours” (Martin 1970).

The intended use of the stationary engine at the west end of the Causewayend incline seems to have been modified at an early date. Experiments showed that the new locomotives, with a tender and five loaded wagons, could achieve speeds of four or five miles an hour on it. As the hill was relatively short this made little difference in the whole rate of speed along the line, and saved the time and hassle of connecting the cables (Sheffield Independent 12 December 1840, 5). It was the steepest incline on normal adhesion railways in Great Britain used by passenger-carrying trains and shared this distinction with the Ballochney Incline (Wishaw 1840). Goods wagons appear to have continued to use the stationary engine.

In the summer of 1840 the Slamannan Railway appointed George G Dodds as their superintendent of locomotives He was a son of George Dodds who had designed the first Monkland & Kirkintilloch locomotive, and had been working as the foreman at the Kipps Works of the Monkland & Kirkintilloch Railway.

The Union Canal Company was delighted to see the return of a passenger service on its canal. It had previously abandoned its joint project for the inter-city route with the Forth and Clyde Canal Company due to competition with stagecoaches. However, that mode of transport soon upset its plans on this route as well. At the end of November 1840 John Croall & Company announced that they had entered into an arrangement with the “Glasgow and Slamannan Railway Company” (sic) to carry their Passengers between Causewayend and Edinburgh, stating that its coaches would “travel at a speed far exceeding the present Conveyances” (Scotsman 25 November 1840, 1). The stagecoach to connect with the first daily Causewayend-Glasgow train left Princes Street at 7am, the same time as the canal boat was leaving Port Hopetoun. To catch the latter, however, it was necessary to leave Princes Street by omnibus at 6.45am. The stagecoach connection was therefore a quarter of an hour speedier from the centre of Edinburgh. The road connection with the later train that day was even quicker in comparison with the canal boat, the departure from Princes Street being a full half-an-hour earlier. The Edinburgh-Glasgow fares by the coach route were dearer by 2/- First Class and 6d Second Class.

The speedier connection given by the stagecoach greatly impressed the Garnkirk & Glasgow Railway who soon prevailed upon the Slamannan Railway to favour the coach route rather than the canal. The timing of the canal boat was also unreliable. On 5 November 1841 it was reported to the Union Canal Management Committee that the Slamannan Railway Company had given notice that their trains would in future leave Causewayend at 2.15pm sharp,

“even although some accidental detention should have prevented the arrival of the boat till a few minutes after that hour; thus rendering it a matter of extreme hazard for the canal company to sell through tickets”

(Martin 1970).

About the same time the railway ticket office at Glasgow stopped selling through tickets to Edinburgh via the canal connection, through railway/stagecoach tickets only being offered (ibid).

The Slamannan Railway Company had by this time discovered that the passenger service was not proving as remunerative as expected, whether in connection with the Union Canal or with the stagecoaches. They applied to the Garnkirk & Glasgow for a reduction in their levy per passenger, and in December 1841 this was granted. The charge was reduced from 3d per passenger (plus 1d mileage tax) to 1d per passenger (plus 1d mileage tax). The through service was not destined to have a long life, however, and the opening of the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway on 21 February 1842, offering a far superior service between the two cities, virtually put an end to it. The entries in the Slamannan ledgers for tickets sold at the Garnkirk & Glasgow offices in Glasgow cease abruptly on 19 February. The Slamannan Company wanted to continue the service hoping that the Garnkirk & Glasgow would agree to a further reduction on dues, but the latter company were unsympathetic (Martin 1970). Instead, a local service from Airdrie to Casuewayend, of the kind envisaged when the company was first promoted, was instituted.

There were originally three passenger stations on the Slamannan Railway – at Slamannan, Avonbridge and Causewayend. These are the stations listed in the early advertisements, and salaries for collectors at these places were entered in the Slamannan ledgers. In addition, the Slamannan Railway Company appears to have constructed and operated a station at Commonhead, on Ballochney Railway metals, to serve the town of Airdrie. The Slamannan ledgers contain an entry, dated February 26 1841,

“To cash paid J. & M. Loudon, per Alexr. Paterson, in full of their account and detailed schedule of measurement for erecting a passenger station house at Commonhead,,, £35.9.8.”

The Slamannan Company also paid a collector at Commonhead. After the passenger service was reduced to a local one between Airdrie and Causewayend, the Airdrie terminus was listed in timetables as Airdrie (Rawyards). Sometime during the 1840s a station was opened at Glenellrig, between Slamannan and Avonbridge. This station was closed on 1st January 1850, it having been found that

“the drawings at Glenellrig were not sufficient to defray the expense of keeping a ticket seller there”

(Martin 1970).

Another station was opened nearby at Bowhouse in the late 1840s and at Blackstone in January 1863.

The Slamannan Railway owned four passenger and two luggage or goods engines. The passenger locomotives were named “Boanerges,” “Borealis,” “Rose,” and “Thistle;” and the goods locomotives “Slamannan” and “Glenellrig.” “Boanerges” and “Borealis” were built by J.M. Rowan & Co of Glasgow and “Rose” and “Thistle” by William Fairburn of Manchester, while “Slamannan” was built by the St. Rollox Foundry Co and “Glenellrig” by Murdoch, Aitken & Co. The latter engine was not long in Slamannan Railway stock. It was delivered in January 1841 and sold to Messrs Jeffs & Sons, contractors for the Dublin & Drogheda Railway, in October of the same year (Martin 1970).

The details of the transportation of “Rose” and “Thistle” from Manchester are worth recording. They did not make their way north on the rail network because it was still under construction and was of a different gauge. From Manchester to Liverpool they were shipped by way of the Bridgewater Canal and the Mersey by the New Quay Company of Manchester for the sum of £21.15.. From Liverpool to Kirkintilloch the Carron Company were in charge of the shipment, and were paid £63.0.0. The boilers were shipped separately on board the schooner “Latimer” from Manchester to the Broomielaw, Glasgow, the captain of the “Latimer” being paid £67.10.0 plus 16/- river dues. From the Broomielaw the boilers were removed by road to the Garnkirk & Glasgow Railway at St Rollox, and from there they were transported to Kirkintilloch by way of the Garnkirk & Glasgow, and then the Monkland & Kirkintilloch Railways. A temporary shed was put up at Kirkintilloch for the fitting up of the engines at a further cost of £15. Once re-assembled, the engines travelled to the Slamannan Railway by way of the Monkland & Kirkintilloch and Ballochney Railways which had the same 4ft 6ins gauge as the Slamannan Railway.

To the people on the sleepy Slamannan plateau the coming of the railway was truly amazing. Many of the population were completely unfamiliar with this latest piece of technology and some did not know how to behave in its presence. A curious young girl named Johnstone decided to experiment with the engines at Bogo, a little to the west of Avonbridge. She placed two stones on the tops of the rails to see if the engine would “ding off the stones, or the stones ding off the engine and train.” Fortunately, however, the engine crushed the stones and passed over them without doing any harm. So she tried the experiment with larger stones and was caught by one of the Slamannan Railway Company’s policemen. She was put on trial before the Circuit Court at Stirling, as an example to others who might be inclined to make experiments which endangered the lives of travellers, and was sentenced to six months imprisonment (Falkirk Herald 26 August 1841, 2; Scotsman 29 September 1841, 4).

A high point in the transport of passengers occurred in September 1842 when Queen Victoria visited Linlithgow. The loyal public flocked to the town to see her and in the evening the train returning to Airdrie and Coatbridge presented an amazing sight. It had no fewer than 116 carriages (chiefly open wagons) filled with 1,500 passengers. It was propelled by five locomotives, and had a length of about a third of a mile (Witness (Edinburgh) 21 September 1842, 3).

The Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway through Falkirk ran a thoroughly modern service. This new world included Sunday services which were greatly opposed by the even newer Free Church of Scotland. When it held its General Assembly in Glasgow in October 1843 it boycotted the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway due to its unholy and accursed Sabbath traffic. For one brief moment the Slamannan route by way of the Union Canal was revived, but it was very brief (Witness (Edinburgh) 18 October 1843, 2).

The impact of the railway on the economy of the hitherto dormant little hamlet and parish of Slamannan was immediate. Writing in 1841 the parish minister was clearly excited:

In 1859 the Ordnance Surveyors described the railway station at Slamannan as :

“extremely small and principally built for the convenience of passengers.”

It was located half a mile to the south of the small village and was meant to serve the sparse rural population. As the number of inhabitants rose exponentially there were constant calls to have the station enlarged but that did not occur. Goods and livestock were handled at the station, which had a small yard with a weighing machine attached. Livestock fairs were held in April and November on land near Rosemount School and special trains were laid on for this event.

“Greater facilities will now be furnished for promoting the general industry and prosperity of the parish, by means of the railway passing obliquely through the parish… Since the commencement of the railway, there have been different bores made on the lands of Balquhatstone, for ascertaining the nature of the metals, and after a depth of 25 to 30 fathoms and upwards, there have been found several seams of coal from 1 to 3 feet thick. A pit has lately been opened, and a steam engine erected by Messrs J. Russell of Leith, tacksmen of the coal; and at the depth of 12 fathoms have found a seam of good coal, 3 feet thick, with a free-stone roof. About twenty-five workmen are employed, and nearly fifty tons daily of coal are conveyed to market by the railway, the selling price being 4d per cwt. on the hill. Other trials in different districts of the parish have recently been made, and smithy-coal and abundance of fine freestone have been found. The railway being now finished, and a year nearly in operation, the minerals have become an object of acquisition, the parish will increase in population by the erection of villages, and thereby an additional stimulus will be given to agricultural pursuits”

(Davidson 1841).

Running passenger trains was not without incident. On Saturday 2l October 1844 the passenger train was returning from Causewayend to Airdrie when it went into a siding or off-let opposite Mr Gardner’s sawmill at Bankhead near Avonbridge, and crashed against a waggon filled with stones, propelling the waggon a good distance from the lye. Luckily none of the passengers were very severely hurt and all went away on their feet. One person perceiving the danger had sprung from the fast moving coach before it hit the wagon and also escaped unhurt. It was subsequently ascertained that the accident was owing to the man who took the waggon into the off-let having forgot to shut the points (Stirling Observer 3 October 1844, 1).

The need to tranship all of the goods and minerals going eastward onto barges meant that the trade to Edinburgh remained weak. In 1841 mineral receipts for the Slamannan Railway amounted to £1,271 (from 26,776 tons) compared with £6,174 from passengers. The mineral tonnage climbed steadily, rising to 74,130 tons in 1845. The opening of the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway had killed the passenger traffic but, in the best ways of management, the directors saw it as an opportunity for the transport of minerals. At Causewayend they were close to the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway and a connecting line there was the solution.

The suggestion of extending the Slamannan Railway at its eastern end to join the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway was well received. The proprietors of the Edinburgh & Glasgow were persuaded to subscribe half the cost of the connecting link, and a nominally independent company, the Slamannan Junction Railway was promoted in parliament, getting its Act passed on 4 July 1844. It was to run from Causewayend to the Bo’ness Junction (later renamed Manuel High Level) on the Edinburgh & Glasgow line. Shortly after obtaining the Act the shareholders sold the Company to the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway and it was that company that built the line (this will be dealt with separately) on the standard gauge. The work was finished by January 1847, but it did not come into operation until August 1847 by which time the Slamannan had converted its gauge. The opportunity was probably taken to get rid of the old stone blocks and to replace them with wooden sleepers. These gave a smoother ride as they absorbed some of the shock of the trains passing over them. At the October annual general meeting the Slamannan Railway Company remarked that :

“The Slamannan Junction line being now open, and traversed by your engine and carriages, the traffic interchangeable between your lines and the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, in minerals, goods, and passengers, has increased and is increasing. Since the assimilation of the gauges, the passenger traffic on the Slamannan Railway has considerably increased”

(Herapath’s Railway Journal 16 October 1847, 21).

A Special General Meeting of the Slamannan Railway was held at Glasgow on 26 February to authorise it to raise the sum of £7,050 by the creation of additional capital in respect of the outlays incurred in widening the gauge of the line, and in finishing the Strathavon Branch to Jaw Craig. 141 £50 shares were issued, guaranteed to yield a dividend of 5 per cent per annum (Herapath’s Railway Journal 11 March 1848, 14). At the same time a branch leaving the Slamannan Railway at Blackston for Bathgate was in the offing.

The Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway started negotiations in 1844 to take over the various railways between Causewayend and Airdrie stating that it would change them to standard gauge. After a rebuttal, it withdrew the offer on 31 December 1846. For some time the Slamannan Railway and the Monklands & Kirkintilloch Railway had been co-operating closely and their management was now shared. This is clearly illustrated in the following advertisement:

“MONKLAND RAILWAYS COMPANY. NOTICE TO CONTRACTORS, SURFACEMEN, &c. THE DIRECTORS of the Monkland and Kirkintilloch, the Ballochney, and the Slamannan Railways, are ready to receive Offers for the Maintenance of Way of their Lines of Railway and Branches.

The Lines will be divided into lengths of from two to three miles; and Contacts will be entered into for one year from and after 1st February next.

Copies of the Specification may be had on application at this Office, or to Mr Dodds, the manger, at Mosside, on and after the 15th; and sealed offers will require to be lodged with the Subscriber on or before Wednesday, the 26th January current…”

(Glasgow Courier 13 January 1848, 3).

On 14 August 1848 the Slamannan Railway merged with the Monklands & Kirkintilloch Railway and the Ballochney Railway to become the Monklands Railways. A 4½ mile extension was built to Bo’ness, opening on 17 March 1851 as the Slamannan and Borrowstounness Railway (this too will be covered separately). The 26 June 1846 Act of Parliament authorising this extension also allowed the railway to lease the harbour at Bo’ness but this lease was not followed through.

The inclined plane of Causewayend was evidently still in use and in May 1849 David Sharp was bruised between some wagons which came in contact with each other there. He died within a few hours of the accident (Falkirk Herald 10 May 1849, 2). Another accident occurred there in March 1877 when a young lad named James Grant, who was employed by the North British Railway Company at the Incline, jumped from an engine to uncouple some wagons and fell before the tender. Its wheels passed over and severed his foot from the leg above the ankle. He was immediately conveyed to Bo’ness, from whence, having been examined by Dr Graham, he was sent to Edinburgh Royal Infirmary (Falkirk Herald 15 March 1877, 5).

It was, however, the sidings that presented the greatest danger to the employees of the railway. This could be due to shunting operations, the points being incorrectly set, or the presence of stray wagons on the main line. Examples are given in the appendix. Accidents were an occupational hazard of working on railway and the staff were loyal and long-serving. William Bryce, for example, was engaged as a message boy during the construction period in 1838. When the railway opened for traffic in 1840 he got a gate to keep at Blackston level crossing. In 1844 George Dodds put him on cleaning the engines; and when the Hallcraig Station was opened in 1845, he got to be a fireman, and in 1848 a driver. From 1865 to 1887 he drove passenger trains (Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser 11 June 1887, 4).

In 1855 the Bathgate branch was finally opened. It featured a viaduct over the River Avon at Westfield and will be dealt with in a separate article. The Causewayend Incline had originally been laid with light rails. The increase in the amount of traffic and the heavier weight of the rolling stock meant that in 1856 they were giving way and so the rails were replaced at a cost of £616.5.7 (North British Daily Mail 7 August 1856, 2). At this time the two engines at Causewayend, and one at the Ballochney Incline, were said to be in good condition. The winding engines continued to be used until about 1865, by which time locomotives were powerful enough to deal with the incline on their own. The stationary engines were sold off in 1869.

The commercial performance of the Monkland Railways improved a little, but they were unable to compete against the more modern railways, and they were absorbed by the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway on 31 July 1865. A day later the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway was absorbed into the North British Railway.

The station at Slamannan saw little by way of enhancement over the decades. Not only was the waiting room far too small, but there was no footbridge over the adjacent main road from Slamannan to Limerigg for pedestrians. In 1900 James McGuire Watson, merchant, New Street, Slamannan, was killed traversing the level crossing. His widow sued the North British Railway, which pointed out that he should have used the under bridge at Binniehill and the footpath from there to Burnbrae (Edinburgh Evening News 16 May 1900, 3). It was a rather circuitous route.

After the riots by the Irish navvies during the construction of the Slamannan Railway things were much quieter and it was rare to see a policeman present. However, the prosperity of the mid century slowly declined and by 1878 the numerous colliers in the Slamannan area were facing pay cuts. Relations between the colliers and the pit managers deteriorated and matters came to a head on 18 April 1878. Anticipating trouble Daniel McDonald, the superintendent of police in Falkirk, sent two policemen to the village. A large crowd of miners congregated to the south near Limerigg and the police went to Slamannan Station to await them.

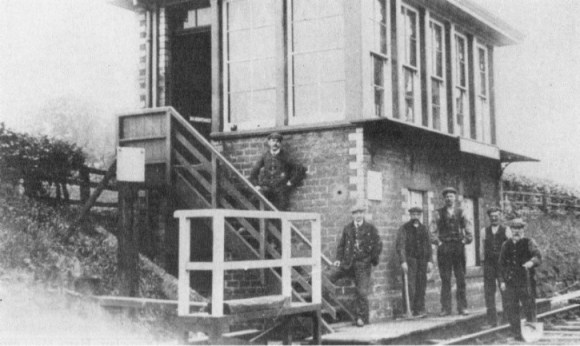

They soon realised that their situation was untenable and that the gathering numbered well over a thousand men, women and children. A message was sent to Falkirk and Inspector McDonald arrived there later that day with another two policemen to see for himself. Before long the “mob” led by a brass band arrived at the railway station and stones were thrown at the police and the adjacent signal cabin where the manager of Balquhatstone Colliery had taken refuge. In just a few seconds hundreds of stones shattered all of the glass. The mob seemed satisfied with its work and momentarily withdrew. The police were helpless and took refuge in the village. The colliers, however, were not finished. In the village the home of the coalmaster, James McKillop, was almost gutted (see Binniehill House). McDonald returned the following day with a large number of policemen collected from Falkirk and Stirling (Falkirk Herald 8 August 1878, 2).

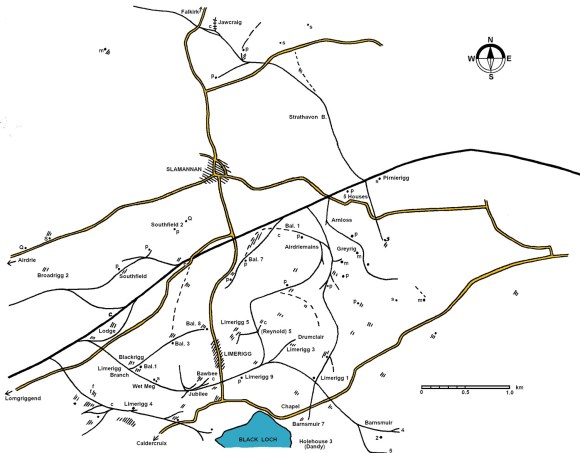

The performance of the Slamannan collieries improved and each built its own sidings onto the mainline and soon the area was criss-crossed with a network of mineral lines. On these the wagons were worked by short-axis locomotives known as pugs which could cope with the tight curves. Branch lines left the main line in the parish; Southfield Branch served the collieries to the west of Slamannan; North Monkland Branch served those further north-west; the Limerigg Branch was fed from the Limerigg, Balquhatstone, Drumclair and Barnsmuir collieries; whilst the Strathavon Branch led to the Jawcraig pits and from there to Garbethill.

In January 1891 the employees of the North British Railway went on strike. All traffic westward along the Slamannan Railway ceased and only limited movement occurred to the dock at Bo’ness. As a result the pits at Slamannan were unable to work and the men were laid off for six weeks or so. The coalmasters did their best to work the mainline with their own engines and drivers. They met with limited success and even this was thwarted by the intimidation of the drivers by “strangers.” A year later is was reported that there was only twelve years’ worth of coal left in the Slamannan coalfield and a gloom grew over the area. On 2 February 1892 the station at Longriggend was totally destroyed by fire (Glasgow Evening Post 3 February 1892, 7).

It was 1892 before the North British Railway Company inaugurated the tablet system of signalling on the single line of the Slamannan Railway. Using this system the driver received a tablet (a small square plate) from the signalman, which he had to deliver up at the next signal cabin before the train was allowed to proceed further. In this way only one train could be working on the main line between each cabin at any one time. The new system used instruments developed by Tyer & Co and was first rolled out that October at Slamannan Station and the cabins to either side.

Coal extraction on the Slamannan Plateau went into a steep decline in the first two decades of the twentieth century. As the pits became uneconomic the branch lines closed – Southfield and Lodge in 1905. In 1918 the old stationary engine house on the Causewayend Incline was demolished by the North British Railway. The unique datestone was to be taken out of its façade and rebuilt into a wall at the station near the Union Canal. In 1954 the Royal Commission saw it built into the north face of a brick-built water tank some 260yds west of the Causewayend Basin (RCAHMS 1963, 441). It is now in the collections of the National Railway Museum at York. Passenger traffic was withdrawn on 1 May 1930, after which only an occasional special train was run for day excursions to such places as Burntisland.

The approach of the Second World War left the Admiralty scrabbling around for sites to store some of the ammunition needed to supply the Navy’s ships on the Firth of Forth as it would be dangerous to have it all at Rosyth or Crombie. Good railway links were essential and for speed of delivery (and cheapness) it was decided to store the munitions in the railway wagons and vans. Rural locations were essential to avoid casualties in the event of any mishaps, and to provide a measure of protection from air attack long stretches of disused deep curvaceous cuttings were ideal. The Slamannan Railway from Causewayend to Blackston fitted the bill and so an ordnance depot was established there for the duration of the war and given a measure of protection (Bailey 2023, 161-165).

The remaining stations closed in the years after the war. On 1 September 1949 the depots at Slamannan and Longriggend were closed, and Causewayend followed in November 1952. By 1953 even the rails had been lifted along that stretch of the line between Slamannan and Avonbridge. From Avonbridge to Manuel was now a separate branch, as was the section from Slamannan to Airdrie. Life at Airdrie (Rawyards) station ended on 1 May 1956, Whiterigg on 1 August 1956, Commonhead on 1 July 1959, Bowhouse on 6 July 1964, and finally Avonbridge on 28 December 1964.

Today

Although disused for decades, much of the line can still be traced on the ground though only short sections are open to the public. By far and away the best place to start is at the east end of the Slamannan Railway at the Causewayend Basin. The basin was partially cleared of its rank vegetation after the successful completion of the Millennium Link project and so is now used by canal-going boats. Scottish Canals put floating pontoons in for this purpose. To the west of the basin is a large flat triangular area which formerly acted as a goods yard but today is infested with saplings. A path takes the walker 760m up the Causewayend Incline and in doing so passes under a substantial stone farm bridge and over a tall bridge crossing a minor road. Just beyond this bridge the embankment curves to the south-west and at this point stood the winding engine – now just an empty space.

The footpath continues on along the embankment between Loan and Gillandersland Farm to the B825. Beyond that it lies in private land which includes the site of the Bowhouse Station. Turn right (west) along the B825 and take the A801 towards Torphichen at the Bowhouse roundabout. After a short distance the road to Candie branches off to the right, crossing the old railway as it does so. It is not possible to follow the railway here, but 845m further on turn left and then after 490m the line reappears in a cutting and westward a public footpath runs along it for just over 750m. This is one of the stretches that was used in the Second World War for the munitions trucks.

The site of the station on the B8022 is now a public park, but from here a footpath leads off to the west along the Binniehill Embankment. Although the bridge over the Binniehill Road has been demolished, it is still possible to follow this path for 1.2km west of the station, almost as far as Lodge Farm. Again it disappears into private land, but a worse fate awaits the west end. At Stanrigg opencast mining has removed all trace.

Westward only glimpses may be had of the old railway from the public roads. At Blackston road near Hill Farm it crosses the line on a magnificent stone bridge.

From here to Bogo Farm the track has been eradicated by farming, though re-used stone blocks can be seen in Avonbridge. Another stone bridge occurs at the River Avon. The line westward survives as wooded embankments and cuttings but is private as far as Slamannan Station.

Appendix – Accidents

2l October 1844 – the passenger train from Causewayend to Airdrie went into a siding at Bankhead near Avonbridge and crashed against a waggon filled with stones. None of the passengers were very severely hurt. One person perceiving the danger had sprung from the fast moving coach before it hit the wagon and also escaped unhurt. The accident was owing to the man who took the waggon into the off-let having forgot to shut the points (Stirling Observer 3 October 1844, 1).

May 1849 – David Sharp was bruised between some wagons at the Causewayend Incline and died within a few hours (Falkirk Herald 10 May 1849, 2).

14 September 1850 – the train from Linlithgow to Airdrie was proceeding at a rapid rate near Slamannan Station when it suddenly dashed off into one of the sidings, tore up the rails, upset one of the carriages, and considerably injured one of the passengers. The iron coupling which connected the carriages to the engine snapped and the engine ran forward about fifty yards and earthed itself, leaving the carriages behind. But for this, the results would have been disastrous (Stirling Observer 19 September 1850, 2).

29 April 1851 – a goods train from Causewayend was proceeding westwards and stopped at Arnloss to have some wagons taken off. John Livingston, a guard, uncoupled the vehicles from the engine and sitting on the foremost ran them into the lye or siding. On jumping from his seat he missed his footing and fell in front of the wagons. He was severely injured and died within minutes (Falkirk Herald 1 May 1851, 2).

10 August 1851 – the keeper of the gates at the level crossing at Avonbridge, thinking that all the trains had passed for the night, shut the gate across the line and retired to rest. He was mistaken, at twelve o’clock a very long train of coal wagons going towards Airdrie, and drawn by two engines, went through both gates, dashing them to splinters. The porter at the gate was dismissed for his negligence (Falkirk Herald 14 August 1851, 3).

15 February 1853 – the passenger train that left Airdrie at 5.30pm for Linlithgow proceeding on its way and a short distance beyond the Causewayend Station, it came into contact with an empty coal waggon that had been left on the rails. The train had just left the station in the dark and so was moving slowly and consequently the shock, though violent, did no damage to the passengers. The coal waggon was wrecked and the engine partially thrown off the rails. It was within a few yards of the canal, and had the shock been such as to throw the engine over the embankment, both it and the passenger carriages would have been precipitated into the canal (Falkirk Herald 17 February 1853, 3).

September 1854 – some wagons were being driven on to the Causewayend Incline when they started down it before the brake had been secured. Four of them were smashed to pieces at the bottom. Mr Wilson, the station master, saw them coming and removed the check rails at the bottom of the incline so that the wagons did not run on to the Edinburgh and Glasgow line (Falkirk Herald 28 September 1854, 3).

2 November 1854 – while James Russell, a fireman, was coupling some wagons to a train near to Slamannan, the engine on some account was backed, and Russell was caught between two wagons and crushed. He died a few hours afterwards (Christian News 11 November 1854, 4).

7 November 1860 – an engine and mineral train left Avonbridge a little after 11am and came into collision with another engine and train coming in the opposite direction. The drivers and brakesmen let from the engines before contact and escaped unhurt. Both engines were destroyed. The line was not cleared when the 6pm Airdrie to Bathgate passenger train arrived and so the passengers walked past the debris and resumed their journey in coal trucks (Southern Reporter 8 November 1860, 4).

14 April 1863 – 48 year old George Brownlee, along with some others, was employed running filled wagons from a weighing machine down a siding, and coupling them together. Brownlee had charge of the second wagon, and the adjusting pin of the brake being out, it fell down on the plummer box. Thinking that this was all right, he pressed the handle down, but unfortunately it slipped off the box and he was thrown in before the wagon. One of the wheels passed over his head, killing him instantaneously (Dunfermline Saturday Press 18 April 1863, 3).

24 August 1864 – A cow strayed onto the Slamannan Railway as was run over by an engine and killed. The train ran off the line and both engine-diver and stoker were injured (Scotsman 27 August 1864, 2).

23 February 1866 – The 4.30pm passenger train from Airdrie reached Avonbridge about 5.25pm but the engine driver reported to the stationmaster that he was unable to take the train forward. The stationmaster therefore sent a mineral engine, which was standing at the station, with the passenger carriages to Manuel Junction. The passenger locomotive slowly backed towards Slamannan to search for a pin or bolt which was missing from the right valve-spindle. Not finding it the locomotive was returning to Avonbridge when it hit the on-coming mineral train which was travelling tender first with two carriages and a break van behind. The buffer beam of the tender was knocked off, and a hole made in the tank. The Tyer’s instrument for single line working had been overruled by the Avonbridge stationmaster who had not realised that the train was returning from the Slamannan direction (Falkirk Herald 16 June 1866, 2).

25 November 1869 – Thomas McCulloch, manager at Nappyfaulds Colliery, went to Slamannan Station to procure some wagons for his works. McCulloch got into one of the wagons and they were pushed by a locomotive onto the Strathavon Branch. Two of the wagons came off the rails and rolled down an embankment. McCulloch was crushed and died ten minutes later (Glasgow Herald 30 November 1869, 4).

27 February 1871 – William Hamilton, in the employment of W. Black & Sons, coalmasters, Southfield, near Slamannan, was in the habit of going to Slamannan village daily for a newspaper for his employers, and walked along the Slamannan Railway line. He was returning when he observed the North British passenger train from Airdrie approaching and to avoid it he stepped to a siding where a goods train was being shunted. In doing so his foot was caught between the rails at the points, and before he could extricate himself the engine and five wagons passed over his body. Hamilton died at Broxburn in the course of his removal to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. He was 45 years of age (Glasgow Herald 28 February 1871, 3).

19 November 1873 – Hugh Murphy, 35 years of age, a miner, was walking along the railway near Slamannan in a state of intoxication when he was run over by a train and killed (Scotsman 21 November 1873, 4).

18 December 1873 – John Eadie, aged 15, was walking on the railway to his home at Roughrigg when he was caught by an engine and dragged 15 yards resulting in his death (Scotsman 18 December 1873, 5).

3 October 1874 – two colliers and a woman were walking along the line between Avonhead and Airdrie when a train came up in the dark and literally cut them to pieces (Stirling Observer 10 October 1874, 2).

18 December 1876 – a mineral train ran off the line between Rawyards and Commonhead while coming down a very steep incline. A considerable amount of property was destroyed, wagons and goods were strewn along the line and the rails were torn up. No one was injured (Edinburgh Evening News 19 December 1876, 2).

13 March 1877 – a young lad named James Grant, who resided with his widowed mother in Bo’ness, while jumping from the engine to uncouple some wagons at the Causewayend Incline, fell before the tender, the wheels of which passed over and severed his foot from the leg above the ankle. He was immediately conveyed to Bo’ness, from whence, having been examined by Dr Graham, he was sent to Edinburgh Royal Infirmary (Falkirk Herald 15 March 1877, 5).

6 February 1880 – the passenger train to Airdrie was about three-quarters of a mile to the west of Slamannan when the driver felt that his engine had run over something. It was night and dark. He at once pulled up, and returning a short distance, they found Thomas Hindes, a soldier in the 42nd Regiment, lying dead between the rails, and a cousin of his, named James Hindes, miner, Drumclair, lying beside him in a dying state. It was found that the soldier’s neck was broken. James Hinde’s skull was fractured, and both his legs broken, and he was conveyed to the Glasgow Infirmary on Saturday in an unconscious state (Stirling Observer 12 February 1880, 6).

7 December 1882 – Willia, Smith, a railway surfaceman who looked after the points at a siding between Slamannan and Avonbridge was decapitated by a mineral train (Southern Reporter 14 December 1882, 4).

14 February 1883 – Daniel Darroch, a coal miner aged 49 years, was walking home to Lodge along the railway when he was hit by a train and badly mutilated.

25 November 1885 – Margaret Mackay or Robertson was walking home along the Slamannan Railway to Greenhill Rows in Slamannan from Airdrie when, about 300 yards east of Longriggend Station, she was hit by an engine and cut in two (Hamilton Advertiser 28 November 1885, 6).

21 November 1889 – James Sneddon, engine cleaner at Binniehill Colliery, threw himself in front of the 7.20pm passenger train on the railway at Binniehill and was killed (Paisley Daily Express 22 November 1889, 3).

27 May 1890 – Thomas Robertson, 33 years old, an oversman in Slamannan left his house to go on holiday. He got to the railway near the station just ahead of the 6.55am train and thought that he had time to slip across the line in front of it. He failed to reach the platform before the engine and his left leg was badly crushed. He was conveyed to the Royal Infirmary (Glasgow Evening Post 27 May 1890, 5).

18 April 1891 – A boy named Robert Rae was walking along the railway to his work when he was run over near Slamannan Station. His left foot and hand were badly damaged and it was feared that they would require amputation (Glasgow Evening Post 18 April 1891, 4).

12 October 1891 – a subsidence took place near Slamannan railway station which rendered it necessary to slow the passenger trains approaching the station (West Lothian Courier 17 October 1891, 4).

3 January 1892 – James Marry, a surfaceman from Whiterigg, was found lying on the railway with his skull fractured and died shortly afterwards (Glasgow Evening Post 4 January 1892, 4).

4 August 1892 – Robert Richmond, an unemployed miner, was walking to Longriggend along the railway and when near the Mosslye Signal Cabin he was hit by the Coatbridge to Slamannan passenger train shortly before 10.30am. He was pitched to the side of the railway clear of the engine and received a wound to his head (Falkirk Herald 10 August 1892, 8).

8 August 1892 – about noon, a train going east from Longriggend detached a large number of loaded coal wagons at the Limerigg Junction, about 1½ miles to the west of Slamannan railway station. The greater part of these wagons got detached from the brake van and rushed down the slope of the branch-line, dashing with great force into a works engine belonging to John Watson Ltd at the No 3 Pit, Lodge Colliery. Some of the wagons were seriously damaged and the contents scattered. Fortunately no person was injured. The break down van and crane from the Slamannan Railway Company’s workshops at Kipps was soon at the scene of the wreck (Falkirk Herald 10 August 1892, 8).

9 April 1894 – a mineral train was running between Avonbridge and Slamannan in the early afternoon and as it approached Balmitchell Bridge the driver observed a man sitting on the south side of the embankment. When only 20yds away, William Duncan, a miner from Airth, aged 39 years, jumped up and ran towards the line and was struck by the engine. The train was stopped and the badly injured body was put in the guard’s van and taken to Slamannan Station where Duncan died 20 minutes later (Falkirk Herald 14 April 1894, 5).

13 December 1894 – John Little, station master at Slamannan, was run down and killed by a goods train while walking along the line (Edinburgh Evening News 14 December 1894, 2).

2 September 1899 – an engine and van were proceeding from Coatbridge to Bo’ness, when they collided with a passenger engine at Blackston Junction. The passenger engine was thrown off the rails blocking the line. The other engine was not so much damaged, but the guard’s van was partially wrecked. The railway servants, five in number, had a narrow escape, but were not seriously hurt (Edinburgh Evening News 2 September 1999, 3).

1900 – James McGuire Watson, merchant, New Street, was killed crossing the level crossing from Slamannan to Limerigg. His widow sued the North British Railway, which pointed out that he should have used the under bridge at Binniehill (Edinburgh Evening News 16 May 1900, 3).

NB. This list does not include the many accidents and fatalities which occurred on the private railways of the collieries in the Slamannan area. The tracks were used by the general public as short-cuts.

Sites and Monuments Record

| Causewayend Basin | SMR 717 | NS 9613 7613 |

| Slamannan Railway Aqueduct | SMR 1309 | NS 9447 7419 |

| Slamannan Railway | SMR 1243 | |

| Bowhouse Station | SMR 1052 | NS 9461 7513 |

| Manuel Station | SMR 855 | NS 9697 7720 |

| Avonbridge Station | SMR 872 | NS 9111 7290 |

| Slamannan Railway Terminus | SMR 2108 | NS 960 761 |

| Blackston Junction Signal Box | SMR 2143 | |

| Bowhouse Branch Railway | SMR 1960 | NS 9468 7523 to NS 9139 7485 |

| Strathavon Branch | SMR 1953 | |

| Slamannan Junction Railway | SMR 1524 | |

| Slamannan and Bo’ness railway | SMR 1525 |

Bibliography

Don Martin’s excellent accounts of the railways in this part of Scotland form the basis of all subsequent work.

| Bailey, G.B. | 2013 | The Forth Front; Falkirk District’s Maritime Contribution to World War II. |

| Brees, S.C. | 1838 | Railway practice: a collection of working plans and practical details of construction in the public works of the most celebrated engineers… |

| Davidson, A. | 1843 | New Statistical Account of the Parish of Slamannan. |

| Fullarton | 1842 | Topographical, Statistical, and Historical Gazetteer of Scotland. |

| Martin, D. | 1970 | The Slamannan Railway. |

| Meek, A. | 2003 | ‘A terror to them that did evil: a biography of a Victorian Policeman,’ Calatria 19, 109-118. |

| RCAHMS | 1963 | Stirlingshire: An inventory of the ancient monuments. |

| Skempton, A.W. | 1996 | ‘Embankments and cuttings on the early railways,’ Construction History 11, 33-49. |

| Wishaw, F. | 1840 | The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland. |

SRO – Scottish Records Office