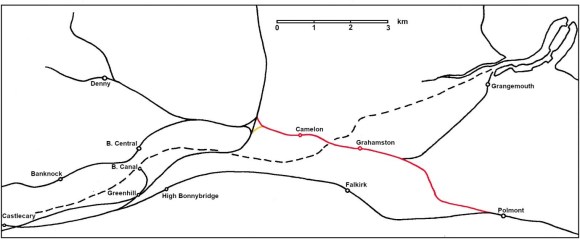

The junction of the Scottish Central Railway with the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway at Greenhill near Bonnybridge gave satisfactory access for trains running between Glasgow and the north of Scotland, but it was inconvenient for Edinburgh. So, a Bill was submitted in the 1846 Parliamentary session for the Stirlingshire Midland Junction Railway from Polmont to a junction at Carmuirs near Larbert, giving a direct connection. It was authorised on 16 June 1846 and even before completion of construction this ostensibly independent line was absorbed into the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway in 1850. To overcome any potential opposition from the Scottish Central Railway it gave that company accommodation at Sighthill, near Glasgow, for its goods traffic.

The railway was a strategic link in the Scottish network but the Falkirk Herald immediately recognised the importance of the line to the town:

“The undertaking is, however, chiefly important to the local trade of Falkirk and its vicinity, from its close connection with the town. The distance and high level at which the line of the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway passes, detract from the advantages which it would otherwise confer. But the proposed railway will actually intersect the town” (Falkirk Herald 13 November 1845, 2).

The landowners along the proposed line were favourable and things moved promptly.

John Miller of Millfield in Polmont, who had engineered the Edinburgh line, got involved in 1845 and helped to steer the parliamentary act for the junction railway through to its Royal Assent in June the following year. He designed the swing bridge to cross the Forth and Clyde Canal at Tophill, but left the construction work to the experienced railway contractor, Alexander MacDonald. Work began on the ground on 9 February 1848 in the east and material dug from the cuttings at Westquarter was used to form the embankments to either side of a new bridge over Callendar Road at the east end of Callendar Park. The progress of the work was reported in the newspapers:

“The works on this line are being prosecuted with great vigour by Mr McDonald, the enterprising contractor who has undertaken their execution. The heaviest part of the work consists of a deep cutting through a hill composed principally of hard blue till, and situated near to Westquarter. Already a formidable impression has been made at this part of the line, and the cutting, which is being carried forward in three “lifts,” is going on merrily, as many men being employed at the different faces, and in dressing the slopes, as can work to advantage. The material arising from the excavation is brought [north] to Callendar policy, where the line passes by an embankment of great height. The contractor has had no less than four miles of temporary rails laid, and the number of wagons tipped is not less than five to six hundred daily, – a number unprecedented, we believe, in the annals of railway works. The bridge across the turnpike road at Laurieston is all but completed, the centring having been last week removed. The appearance which this bridge presents is very striking, the skew being so great that the two abutments stand clear of each other by about eighteen inches. This, it is believed, is the greatest degree to which the principle of the skew arch has been carried in Scotland. The mason work is of the best description, and the whole has been executed in an unusually short space of time. From the manner in which Mr McDonald is carrying forward the works, there is no doubt but that he will complete them within the contract time.” (Falkirk Herald 12 October 1848).

During the digging of the cutting at Westquarter a bed of good quality sandstone was encountered which was suitable for building purposes. Consequently it was used for most of the structures on the railway line and upon its completion the quarry was put up for let by the estate:

“FREESTONE QUARRY, in the Parish of Polmont and County of Stirling, TO BE LET. To be let for such period as may be agreed on, with Entry immediately, the FREESTONE QUARRY on Westquarter Estate, which was opened when the Stirlingshire Midland Junction Railway was formed through that Property, and from which the principal part of the Railway Works on the line were constructed. The post of rock is of considerable thickness. The quality and colour of the stone is very superior. The locality is most advantageous, – either for forwarding the stone to a distance by the adjoining Railway, or by carts in the neighbourhood, where there is a large and steady demand for building purposes… ROBERT CLELLAND, the Gardener at Westquarter House will show the Quarry to intending offerers.” (Falkirk Herald 5 May 1853).

During his work on the railway Alexander MacDonald built several dwellings in the area using stone quarried from the line. These included two at Booth Place and some cottages at the north end of Russel Street known as “MacDonald’s Row” or the “Clachan.”

The bridge to carry the railway over Callendar Road was set at an oblique angle to it and is what is technically known as a ‘skew bridge.’ The skew arch (also known as an oblique arch) was relatively new at the time and as this was towards the extreme end of the range of angles and is in a very prominent position the structure became known as “The Skew Bridge.” It required precise stonecutting.

It was not the only skew bridge on the line and other fine examples will be found at Redding. One of the best examples of mason work in the Falkirk area can be seen at Sunnyside where a minor lane passes under the railway. In the late 19th century this connected the housing on the south at Sunnyside with the blacking mill at Mungal to the north

Great excitement occurred in March 1849 when the cutting north of Camelon encountered a stone culvert from the Roman fort. In it were found two Roman coins. One was a silver denarius of Otho who only ruled for three months from 15 January to 16 April AD 69. The other was larger and of a lower denomination made of copper alloy. A large quantity of lead and an Egyptian travertine urn (at the time of discovery thought to be alabaster (Hunter 2020)) were found further to the west.

In 1850 workmen engaged in forming the sloping banks of the railway-cutting from the bridge that crosses the Carmuirs, exposed a considerable number of pits, from eight to ten feet in diameter, and generally about twelve feet deep. They resembled those discovered at Newstead and other Roman sites, in being chiefly filled with a black, rich, greasy mould, mingled with fragments of bones and other traces of organic remains. A spear-head and axe, with a number of coins, and various fragments of pottery, were also found (Wilson 1863, vol 1, 76). Further archaeological discoveries were made in Callendar Park when a new avenue was cut to replace that lost to the railway (Bailey 2007). These included a number of human skeletons.

“The works on this are being pushed rapidly towards completion. The heavy cutting at Westquarter is in an advanced state, and the only points where operations are at a stand, are the canal crossing and the crossing of the Grahamston road. The manner in which the latter is to be effected has now been arranged with the road trustees, and the work will shortly be commenced. At the crossing of the canal, the contractor has laid down stones for the pier upon which the swing bridge is to rest, but he has not succeeded in getting a beginning made with his building, as, although a coffer-dam has been formed at one side of the canal, it has not yet been made water-tight, nor is it supposed that it will be made sufficient unless the water of the canal is run off. This the Canal Company are averse to allow, and the Railway Company are not entitled under their Act to interfere with the canal traffic except upon payment of a heavy penalty. The railway operations form an object of interest to the inhabitants and are visited daily by streams of people.” (Falkirk Herald 12 July 1849).

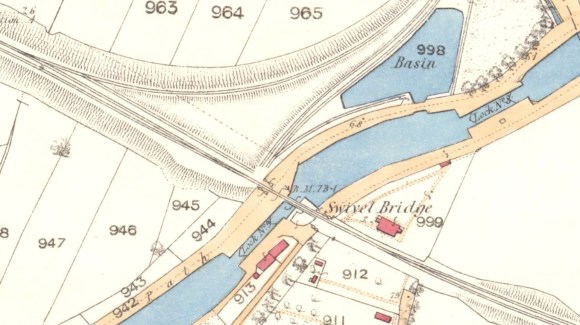

The crossing of the canal just to the north of Lock No. 9 was by far the most difficult task for the builders. Not only was it passing over a water course, but that course had to remain open to navigation during the construction work. The contractor adopted the same technique as had been used during the construction of the Scottish Central Railway a few years before – a temporary channel was built to take the canal off to one side and coffer dams were installed to allow the work to be undertaken on the permanent line. The shifting sands and springs in the area made the task even more fraught. Miller had gone for a swing bridge in order to avoid excessive embankments on boggy ground which would also have interfered with the nearby station at Grahamston. The Forth and Clyde Canal Company had insisted that priority should be given to vessels using its canal. The steel and iron bridge only carried a single line of track. Even at the time this was seen as a possible pinch point, but as traffic increased it resulted in annoying delays.

The Parliamentary Act had stipulated a cantilever bridge with a single span of 50ft, but this would have made it ponderous. Instead, it was agreed with the Canal Company that a bridge of two 25ft spans could be used – being more easily worked, it was to the advantage of both parties. It pivoted on the east bank and the enclosure to take the eastern span when open can be seen on the 1862 Ordnance Survey map; the other span would have hung above the canal reach to the north. There were level crossings at either end of the bridge – one for the canal towpath and the other for Tophill Lane. The gates for these would have been operated by the bridge crew, making the operation far from quick. The trains passing over the bridge were restricted to a speed of four miles an hour.

There were a large number of men involved in the construction work. They were paid monthly, on the first Saturday, when the shops in Falkirk looked forward to their visits. However, there was also a tendency for fights to break out on these occasions (Falkirk Herald 9 August 1849, 3). There were few mechanical devices and it was the muscles of these men, and some horses, that provided the power. At the end of the work the horses were sold off, when they were described as

“twenty of the most famous, powerful, and valuable draught horses which have been sold in Falkirk for several years past, belonging to Mr McDonald, Railway Contractor, Falkirk. The horses are almost all five and six years old” (Falkirk Herald 9 May 1850, 2).

By far the most controversial bridge on the new line was that which took Vicar Street over it from Falkirk to Grahamston. In July 1849 it was announced that the Road Trustees had agreed terms and that construction was due to begun. The public and the local businesses were not consulted. It was with some incredulity that they watched the progress of the work which is neatly encapsulated in this report of 14 March 1850 in the Falkirk Herald:

“For some time back the inhabitants of Grahamston, and the numerous persons who hourly pass up and down Grahamston Road, have halted to look upon a bridge erected across the Stirlingshire Midland Junction Railway, to the east of the road, and to speculate upon the object for which it is intended. Approaches have been formed to the bridge, and an excellent coat of metal has been put upon them, and now the conviction is beginning to grow in the public mind that it is possible it may be intended, – nay, that it actually is intended to divert the prodigious stream of traffic of this great thoroughfare and send it careering over this lofty arch. The extra circuit to be performed ought of itself to have been sufficient to prevent its entering into the conception of any engineer, that the public would tolerate any such diversion. But when, in addition to the detour, the abruptness of the curves, and the precipitous nature of the gradients are looked at, the feeling inspired is one of perfect wonderment. It is to be hoped that the public will speedily recover from their present bewilderment, and that active measures will be taken to protect their interests from this threatened outrage.

To talk of such a thing being permitted, would be a waste of words; and we do not therefore stop here to point out the danger, – the absolute loss that would be entailed upon a large section of the community were the project carried out. It is enough to say that every cart travelling the road would have to mount over the Railway with one-half, or at the utmost, three-fourths of its ordinary load. Let any one watch for half an hour the traffic, and then let him take a slate and calculate, if he can, the annual loss which this would entail! It has been rumoured that the Railway Company have the sanction of the Road Trustees to the intended deviation, but there must be some mistake about this. If it be true, the individual members of the community interested will doubtless have sufficient spirit to protect themselves.”

Twenty of the feuars took out an interdict to stop the work (Falkirk Herald 12 July 1849; 11 April 1850; 14 March 1850). A temporary wooden footbridge was put on the line of the original road. In July 1852 an independent civil engineer, James Jardine of Edinburgh, was appointed as an arbiter in the case (Falkirk Herald 22 July 1852). The outcome of all this was that the almost right angle junctions that the semicircular deviation made with the main road were smoothed out, thus lengthening the approaches and lessening the gradients.

The original scheme had evidently been adopted because it would have been difficult to make the necessary ramps to a bridge on the old line between the existing buildings. Added to this was the advantage that the railway passed through a shallow cutting at the point where the new road bridge was erected. Black’s map shows that there were existing gaps along the road frontage at the points used for the deviation with only the “baths” at the southern point, where it departed from Vicar Street, requiring demolition. The new vehicular route was crescent shaped and became known as McFarlane Crescent.

Meanwhile the Stirlingshire Midland Junction Railway had opened on 1 October 1850 without ceremony – and without a station at Falkirk. Despite the parliamentary bill that authorised the railway requiring that trains to Stirling should stop at Falkirk, few did in the first year. Even then only a perfunctory wooden hut served as a ticket booth. Needless to say the Bairns did not take any of this quietly, but in April 1854, having spent the large sum of £232 on the proceedings in Parliament, the Town Council gave up its law suit. The wooden bridge on the line of Vicar Street now served as a way of crossing to the other platform. Unfortunately there were a number of severe accidents to people using it in wet weather when the steps became very slippery. It was not until 1855 that the treads were replaced with wider ones. Finally, in 1857 a single storey stone station building was substituted for the hut, giving the town the status it felt it deserved.

In September 1852 cattle pens were erected along the south side of the track to the west of the station in preparation for the Tryst that year. This new spectacle attracted the attention of the public:

“the bustle arising from the despatch of the cattle and sheep to all parts of the country being great and incessant. From an early hour in the morning till late in the evening the process of loading trucks with their cargo of live beef and mutton has gone on almost without intermission; and to the bridge above the station, spectators have resorted in large numbers to witness the interesting and amusing scenes which occur below, in the process of embarkation on “board” the trains, as the Yankees phrase it” (Falkirk Herald 15 Sep 1853).

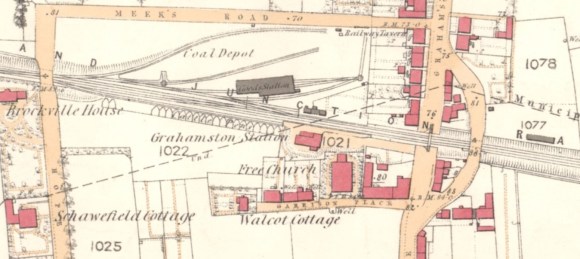

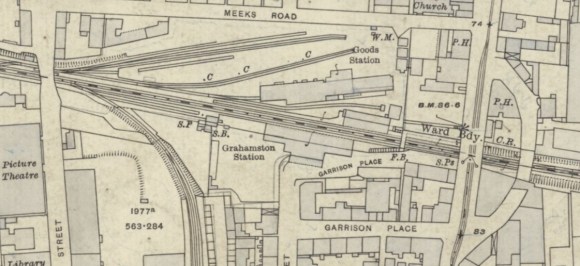

During the October Tryst in 1856 some 400 trucks were loaded with stock at Grahamston Station. Over the following years the droves of cattle disappeared from the roads through the town. In 1866 some 16,000 head of cattle were trucked from the station and four years later two drinking troughs were installed to conform to the Contagious Diseases (Animals) Act. The station became an economic necessity for Falkirk. A goods station on the north side of the railway, with a substantial wooden transit shed and office, had been constructed in 1852. Goods traffic was then diverted to this station from the High Station and the staff was accordingly transferred. It was 1861 before the stables were also transferred. Heavy goods were taken from the foundries by road to the goods yard and in 1863 the east end of Meeks Road was causewayed to cope with this traffic. One other benefit of the station at Grahamston was that in 1856 an electric telegraph was installed and made available for the public to use. The advantages to business were immense.

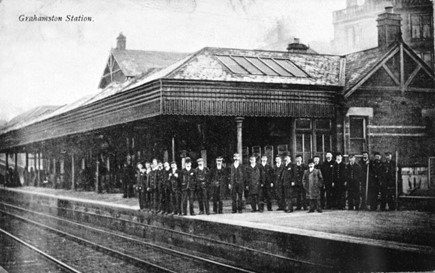

1865 saw the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway Company absorbed into the North British Railway. In March 1865 the shed on the north platform was removed and replaced by a stone and brick structure with a slated roof. It was designed by James Deas, engineer with the NBR. The building was 82½ ft long and contained an office for the station master in the west wing, a storeroom for the porterage business on the east, a lamp-room behind, with a glass-roofed veranda in the centre overreaching the platform. This new station house was described as “more chaste than imposing” by the reporter from the Caledonian Mercury (3 April 1865, 2), though the Stirling Observer called it “exceedingly elegant” (16 November 1865, 5). Three ornate cast iron armchairs were presented by the Falkirk Iron Company.

Although the NBR had eventually renewed the station buildings it was very tardy in undertaking any other improvements and soon gained a bad reputation in the town. What was more, the service was poor and expensive – the result of a near monopoly. Innumerable complaints were received about the unsuitable nature of the wooden pedestrian bridge on the line of Vicar Street/Grahams Road, which the railway company used to get not just the passengers, but also their luggage and parcels from one platform to another. It was too narrow, too steep, too slippery, and altogether too inconvenient and dangerous. Eventually the Town Council had to take the matter into its own hands and got James Deas, by then retired, to design an iron replacement which it had to pay for. The ironwork alone cost £192. The stonework for the piers was executed by Mr Gardner of the mason department and the bridge was complete in the summer of 1872. Despite the fact that it was a public thoroughfare, the employees of the railway company continued to use it and even took hand barrows over loaded with parcels. One irate member of the public complained because one of the two-wheelers was almost as wide as the bridge and that in consequence of the incline such barrows were propelled at such speeds as to be beyond the full control of those supposedly in charge. Before the new bridge was built the NBR had agreed to instruct their engine-drivers to shut off steam at the bridge. However, in 1888 it was reported that not a single train acted upon these instructions. One councillor complained that he had recently got his face blackened, and he had seen smoke do serious injury to passers-by. At 9.20am the nuisance was especially bad, the engine going full force, and nobody could pass for smoke while the train was going under the bridge (Falkirk Herald 11 April 1888, 2).

The existence of the railway led to a number of businesses setting up alongside it and forming sidings. Iron foundries, in particular, were attracted by the availability of land. The Camelon Foundry moved to be near to the line and new ones were established:

| Callendar Iron Works | 1876-1933 | Callendar Iron Co. |

| Camelon Iron Works | 1845-1953 | Camelon Iron Co/Crosthwaite, Miller & Co/ Smith, Fullerton &Co |

| Carmuirs Iron Works | 1899-1968 | Carmuirs Iron Co |

| Central Foundry | 1902-1947 | Scottish Central Foundry Co |

| Dorrator Foundry | 1898-1994 | Dorrator Iron Co |

| Gothic Iron Works | 1899-1964 | Glover & Main/R & A Main |

| Grahamston Foundry | 1868-1990 | Grahamston Iron Co |

| Grange Iron Works | 1883-1963 | Grangemouth Iron Co/Grange Iron Co |

| Parkhouse Iron Works | 1876-c1910 | Parkhouse Iron Co |

| Salton Iron Works | 1894-c1908 | J E Gibson & Co |

| Springfield Foundry | 1876-1907 | M Cockburn & Co/Davis Gas Co Ltd/Wm Pender & Co/Falkirk Diamond Steel Co Ltd |

| Sunnyside Foundry | 1896-1963 | Sunnyside Iron Co/Forth & Clyde & Sunnyside Iron Co |

These augmentations meant that Grahamston Station could not keep up with the demand. To relieve the pressure, the NBR proposed in 1877 to apply for power to make two small sidings, each about half a mile long, to go into some of these works. The Caledonian Railway Company immediately objected that these would interfere with its trade. A Select Committee of the House of Commons considered the lines, known at that stage as No. 6 and No. 7. No. 6 was to be 4 furlongs 88 yards in length, and cost £7,748. It was to join the main line at Callendar Ironworks, and proceed down to the Thornhill Road, providing for the manufactories of the new Etna Foundry and also forming a convenient connection for canal traffic. No. 7 was to be 3 furlongs 52 yards in length, and cost £4,426, leaving the main line at the Bleachfield, and proceed over the intervening fields to Grahamston Foundry. The Bill was passed in August that year and the grounds of Springfield were feued by the Railway Company at a cost of £30 per acre. A new road was formed from the Graham’s Road to a goods depot to be built at Thornhill Road. Construction was rapid and both of these branches were ready for use by the following summer. Falkirk Town Council had been very supportive of the projects as they increased employment and income in the area. It had therefore accommodated the NBR in the process and agreed that a footbridge would be placed over Wallace Street so that pedestrians could use it when the level crossing there was in operation. Mistakenly, it took the Company’s word that this structure would be progressed in a timely manner. After years of bickering the bridge did not appear and the Council learned not to make the same mistake again. In fact it took ten years for the NBR to fulfil its feu charter. When an opportunity arose to oppose another parliamentary bill by the NBR the Council made sure that the negotiated obligations were substantial and legally binding. Given that the two railway companies had broken most of their promises since 1846, it had taken it a long time to come to that conclusion! Of course, the Council also profited in the end because line No. 6 was extended to its gas works, reducing the price of coal at the works, and hence of the gas.

New signalling arrangements were required at Grahamston Station in consequence of the two small branch lines and two new signal cabins were erected. The interlocking and block system, which already existed between Edinburgh and Grahamston was extended to Larbert. Line No.7 was extended to Parkhouse Foundry in 1888 and the siding at Grahamston west signal box was widened to three sets of rails.

The Caledonian Railway Co clearly thought that it had wrung concessions from the NBR by removing its objection to the new branches, and in 1880 it applied for, and was refused, permission to stop its passenger trains bound for Grangemouth at Grahamston. It had had the support of the public in Falkirk, fed up with the behaviour and pricing of the NBR. So, in 1883 the Caledonian Co sought these powers through Parliament, and in August its first passengers alighted at Grahamston. As part of the deal it had constructed a link between the Scottish Central Line at Carmuirs (the Three Bridges) and Camelon – known as the Carmuirs Fork. Both railway companies were to use the fork and have joint use of Grahamston Station. There were now two rival railway companies for taking passengers to Glasgow and the consequence was that fares were considerably reduced. Unfortunately this was not the case for travel to Edinburgh and the public had to pay nearly double the rate to Edinburgh than they were charged to go to Glasgow.

From the very beginning the Stirlingshire Midland Junction Railway was used by famous people. The Royal family were frequent users, passing to and from their Highlands retreat. On such occasions the station was closed to the public, though they often lined the route to get a glimpse. Prime Minister William Gladstone was conducting a tour of Scotland in 1884 to promote his ground-breaking Reform Act and his train stopped at Grahamston Station so that he could deliver a short address to a large and appreciative audience.

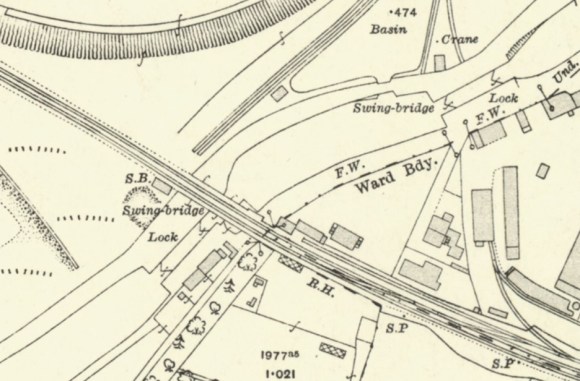

As the amount of traffic on the line increased delays at the pinch point at the swing bridge over the Forth and Clyde Canal became more acute. An express train could be held up to permit the passage of a horse-drawn barge. By then the railway was owned by the North British Railway Company and the canal by the Caledonian Railway Company. Strangely, it was the latter that pushed for an improvement but negotiations between the two over the form that it would take broke down. The alternatives of a tunnel or a viaduct were rejected as too costly. The existing bridge was obsolete and on 13 July 1885 the 7.10pm North British express train from Edinburgh for the north of Scotland missed the facing points at the end of it and tore up the track. Fortunately it was travelling slowly due to the speed restriction on the bridge (Edinburgh Evening News 14 July 1885, 3). The Caledonian Company went to Arbitration Court to compel the NBR to take down and replace the bridge. It was decided to erect a new bridge with a double track which was to be worked by hydraulic power to increase the ease and speed of opening. After comprehensive surveys, work began on site in 1897, supervised by James Bell, the engineer-in-chief of the NBR. Ground conditions made the foundations on the east bank difficult. The ground work was therefore of solid concrete supported by piles. Above that the mason work was contracted to Sharp & Sons, Glasgow. Surfacemen altered the lines of the tracks to either side. A hydraulic tower of brick was erected on the east side and a new and enlarged signal box placed at the west side. The steel superstructure of the bridge and its machinery was supplied by Sir Wm Armstrong, Whitworth & Co, and arrived at Falkirk in sections. During the month of April 1899 a band of mechanics fitted it together on a wheeled platform. Then at midnight on Saturday 22 April work began on demolishing the old bridge. This meant closing the line for two whole weeks and nearly 300 workmen were imported to expedite the task. The old bridge was removed in sections with the aid of a crane and by noon had been completely dismantled. The foundations of the old bridge were then remodelled. The new bridge was wheeled in on the rails and removed from its platform. By mid-day on Monday it had been mounted on its pivot. The necessary hydraulic connections having been made, the bridge was swing for the first time on Tuesday. The following day, and on Thursday forenoon, surfacemen were employed on the new double line, while the bearings of the bridge were also properly adjusted, and the work was pushed forward to such an extent that on Thursday afternoon the bridge was tested in the presence of Mr Bell. It withstood the pressure of a couple of engines without any perceptible failing, and so shortly afterwards a ballast train drawn by two engines crossed. Although tested on the 27 April, it was not till 2 May that the first passenger train crossed – less than the two weeks allowed.

Messrs W.R Sykes, London, contractors for the electrical locking of the bridge, also installed the new lock and block system between Camelon and Grahamston Station signal boxes. The new bridge was supplied with a windlass, with which the structure could be swung, should the hydraulic machinery fail. Water for the hydraulics came not from the canal but from the town’s water supply (Falkirk Herald 3 May 1899, 7). The original plans are now held in the National Records of Scotland (RHP 125291-125305).

The level crossings were now operated remotely from the new signal boxes, speeding up operations.

When the Caledonian Railway Company gained access to Grahamston Station, it proposed a new station building there and acquired Brockville House. However, it ended up with just a passenger booking-office. When the NBR decided to upgrade its station buildings in 1888 it spent the money at the High Station. The public and the Council were vociferous in demanding change at Grahamston and so finally, in 1891 the NBR engineers surveyed the station. Falkirk Town Council agreed to reshape and re-contour Glebe Street, largely at its own cost, to provide direct access from the town centre at an easier gradient. This involved demolishing a cottage in Garrison Place. Plans were passed by the Falkirk Dean of Guild and in August 1893 work began. It was soon clear that the railway company was once again deviating from the plan and had to be brought to boot.

The new station building on the south platform consisted of a brick central two-storey section with three gablets, fronted by a shallow veranda supported on four cast iron columns. The main entrance was in the centre of this block. Set back to either side were single-storey wings. A glass-roofed veranda covered the platform to the north. The complex was slightly to the west of the old building, which was demolished, so that it aligned more with Glebe Street. One result of this was that it no longer faced its opposite number of the north platform.

.

Shortly afterwards the goods depot was upgraded. A large new shed, increased siding accommodation for an additional 500 waggons, extra engine power and a considerable augmentation of the working staff, followed in 1898-9.

Falkirk Town Council now started to look at the area around the station and asked the NBR to open up an access from the north. It also drew up plans for the widening of the bridge. One thing that the Council considered easily achieved was to have the name of “Grahamston Station” changed to “Falkirk Grahamston Station” so that the rest of the world was made aware that the station was actually at Falkirk. On this point the NBR was intransigent.

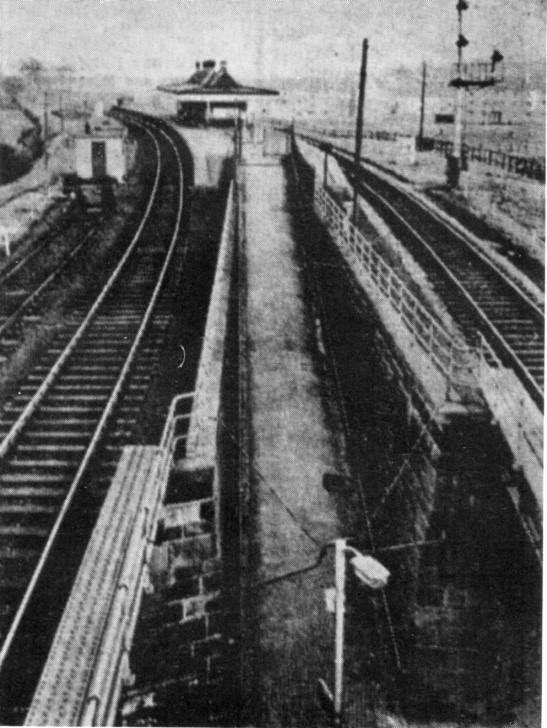

Land had to be purchased from the Grange Foundry Company and the bridge over Stirling Road was widened to allow the track to be re-aligned. The platform building contained the booking office and waiting room and access to it was up a footway with a 1 in 8 gradient which started from Stirling Road between the two sections of the enlarged bridge. The necessary work cost around £8,000.

At the same time as the bridge was being replaced the residents of Camelon, led by Ralph Stark, were petitioning for a station for their village. The settlement had grown dramatically over the previous decades and was attracting much industry. One of the first meetings was held in the public hall on 30 September 1889, but it was 15 June 1903 before Falkirk (Camelon) Station was finally opened. It consisted of an island platform 520ft in length supported on 54 concrete arches of 8ft spans.

.

The official name of the new station was “Falkirk (Camelon Passenger) Station” to indicate that goods were not dealt with there. It prompted a rethink of the names of the other stations nearby. In 1903 Grahamston Station was finally renamed “Falkirk Grahamston.” The other station, “Falkirk” Station, became “Falkirk High.”

In 1900 the NBR realised that in order to improve the performance of its highly profitable goods yard and its branch lines at Grahamston it had to double the track through the station and for that it required another parliamentary bill. Negotiations began at once with Falkirk Town Council and this time the Council played hardball. It managed to wring out an agreement, set in law, that the railway company would replace the road bridge to the east of the station with a broad one with easy gradients placed on the direct line between Vicar Street and Grahams Road, and that it would do so within a three years time period. This would be a public improvement of the first magnitude. The Falkirk Herald was amazed:

“For many a day and many a year the present footbridge over the railway at Grahamston Station has been a source of grievance, of annoyance, of inconvenience, and of danger to the public. Over and over again has the matter been taken up by the Council, and the Railway Company made to promise an improvement, but the promise of a Railway Company, unless made in properly legal and binding form, has a strange and peculiar faculty of remaining unfulfilled” (Falkirk Herald 24 October 1900, 4).

And the timing could not have been better for just five years later it allowed the construction of the Falkirk Circular tramway system.

As if to emphasise the need for the new bridge, one evening in November 1900, John McLean, carter, was so very drunk that instead of going over the old stone bridge on MacFarlane Crescent he actually drove his horse and cart across the footbridge at Grahamston. Thankfully the horse was sober and so they managed narrowly to avoid jamming a female pedestrian against one side of the bridge (Falkirk Herald 28 November 1900, 5). The bridge was already considered unsafe, particularly in wet weather when the public had to crawl across it with the utmost care.

The Council had been studying the problem of the bridge for some time and in 1897 it produced a report stating that the purchase of the buildings and property for its erection would entail a cost of £3,014, but this property and ground could then be resold with altered levels at £2,831 – entailing a loss of £183. Now that the railway company was on board, this was not a problem. Needless to say, the railway company moved slowly on the bridge project. Surveys were undertaken and one and a half years later plans were submitted. Unsurprisingly, the plans diverged from the requirements of the Act. David Ronald, the burgh engineer, was on the case, and produced report after report as each new proposal was submitted. Finally, many adjustments later, planning permission was granted.

The NBR then requested an extension to the three year timetable, which, sensibly, was not entertained. Construction work began and by mid-September 1903 the arch had been formed. In January 1904 the bridge was opened to pedestrians only. The asphalting and causewaying completed, it opened to traffic without ceremony a month later. It was to be another four years before the side walls were completed!

In 1908, in pursuance of their policy of effecting economies, the Caledonian and North British Railway Companies made drastic alterations in the system of working and reduced the number of staff in Grahamston and Camelon Stations. The staff of the Caledonian Company was withdrawn from Camelon Station and its passenger traffic was henceforth entirely dealt with by the North British Railway Company. At Grahamston, the Caledonian staff were withdrawn on 17 March and transferred to other stations. All the Caledonian Company’s passenger traffic was then dealt with by the NBR, which also took over the delivery of parcels on behalf of the C.R. Two lorries were consequently dispensed with. The Caledonian Company’s staff at Grahamston had consisted of an agent, three clerks, a ticket collector and two porters, and to meet the extra work the NBR augmented its staff (Falkirk Herald 14 March 1908, 5). The parcels service suffered a setback in October that year when the office was gutted by fire. Considerable damage was also done to the frontage of the building and the booking hall. By January 1909 it was evident that Brockville House was surplus to requirements and it was sold by the Caledonian Railway to bailie Alexander Aitken at a loss.

An ambulance team was established at Grahamston Station to treat passengers and to train the public in first aid. This provided valuable personnel for the medical services in the First World War. Due to a shortage of manpower Camelon Passenger Station was closed during the war but re-opened on 1 February 1919.

The NBR was absorbed into the London and North Eastern Railway on 1 January 1923; and into British Railways on 1 January 1948. By 1950 the goods shed at Grahamston had been removed and the area became a car park, extended in 1986 by demolishing the coal depot. Camelon Station closed on 2 September 1967.

.

With the closure of the Canal in 1963, the swing bridge was fixed. The east signal box remained open until 1997. The canal re-opened to traffic in 2001, but the swing bridge remains fixed with only modest headroom for passing vessels (around 10ft from waterline).

After years of local campaigning, Central Regional Council agreed to sponsor a new station on the other side of Stirling Road from the original one. The contracts were let by ScotRail and Railtrack on 30 March 1994 and the unstaffed station opened on 25 September 1994. It has no booking office and the waiting rooms take the form of bus shelters. A few years later a footpath was added to provide access over Stirling Road to Nailer Road. This brought the overall cost to about £950,000.

The old railway station at Grahamston was demolished in 1985. The cast iron columns from it were used in the construction of a new bandstand in Dollar Park in 2012. The new station building of 1986 was designed by FJ McCracken for ScotRail and is located on the north platform. It is so placed as to take advantage of a new access from Grahamston Bridge and so is entered on the diagonal with a dominant barrel roof-light. The structure id triangular in plan, giving it an unusual roof line, emphasised by a deep fascia and red trim. A non-descript block waiting room occupies the site of the former station building on the south platform.

The line through the station and onwards to Larbert/Cumbernauld and to Polmont was electrified in 2018 as part of the second phase of the Edinburgh to Glasgow Improvement programme funded by Transport Scotland.

Today

There is much for the railway enthusiast to observe on the ground today. The skew bridges are of particular aesthetic and engineering interest. The second swing bridge over the Forth and Clyde Canal is still in situ – though it is now a fixed link and the associated signal boxes have long since disappeared.

One curiosity is the old entrance to Camelon Station on the east side of Stirling Road. Although it is now bricked up, a handrail protrudes from the blacking wall, drawing the attention of the observer up the slope.

.

Unfortunately, with the electrification, several of the old stone over-bridges were demolished. These included two on the Carmuirs Fork, that to Hallglen near Spink Hill, one near the old cleansing depot at Westquarter, and one near Polmont Station. Their abutments survive.

Sites and Monuments Record

| Stirlingshire Midland Junction Railway | SMR 2125 | |

| Camelon Railway Station | SMR 1969 | NS 8698 8070 |

| Grahamston Railway Station | SMR 1547 | NS 8869 8025; NS 8876 8027 |

| Westquarter Quarry | SMR 2173 | NS 9126 7854 |

| Tophill Signal Box | SMR 2048 | NS 8789 8049 |

| Grahamston Roman Finds | SMR 1090 | NS 88 80 |

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 2007 | ‘An Early Timber Hall at Callendar Park, Falkirk; with a note on the Antonine Wall,’ Calatria 24, 37 -57. |

| Hunter, F. | 2020 | One of the most remarkable traces of Roman art…’, Breeze & Hanson (ed) The Antonine Wall: Papers in Honour of Professor Lawrence Keppie, 233-252. |

| Wilson, D. | 1863 | Prehistoric Annals of Scotland. |