The Development of Steam Power on the Forth and Clyde Canal

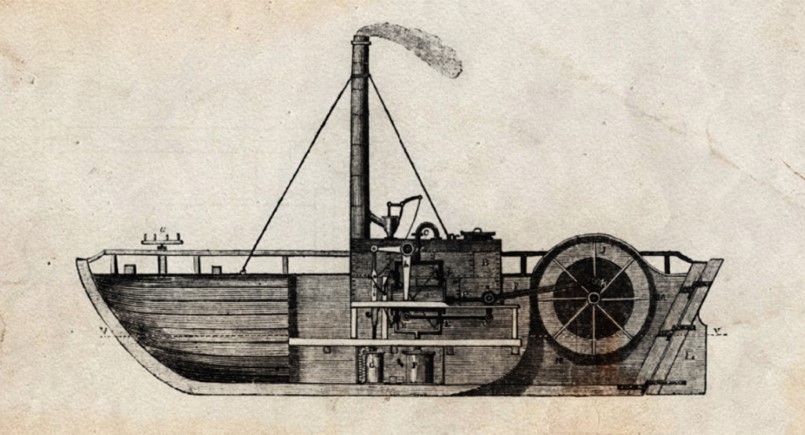

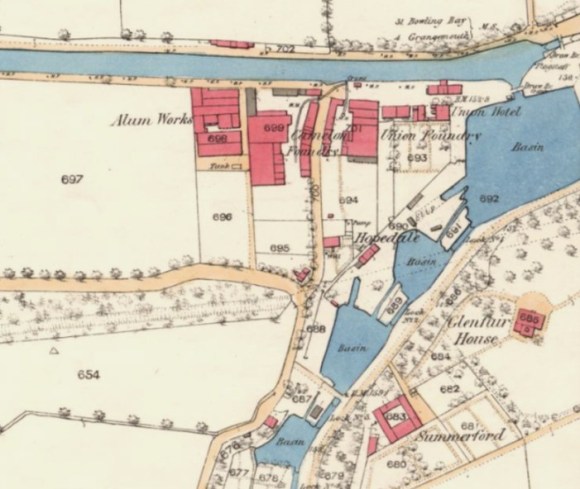

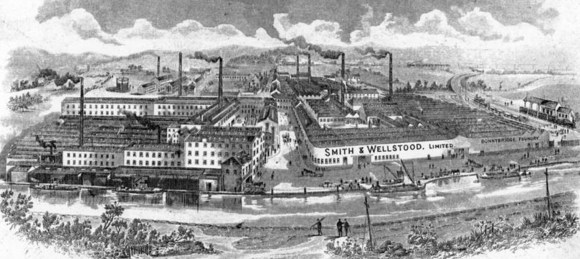

It is well known that the whole use of steam power in ships begins on the Forth and Clyde Canal with William Symington and the Charlotte Dundas in the period 1788-1803. The story is well covered (for example by Bowman 1981, and on the web) and so will not be repeated here. However, the rejection of the Charlotte Dundas due to the fear that the wash from the paddle wheel would damage the banks of the canal was not to be the end of the story for this innovative part of the world. In 1818 Thomas Wilson constructed the first iron vessel made in Great Britain, the Vulcan, for the Forth and Clyde Canal (Shovlin 1996). He then went on to become overseer for the eastern part of the canal, based at Tophill near Camelon, before moving to Grangemouth to supervise the huge improvements to the port there.

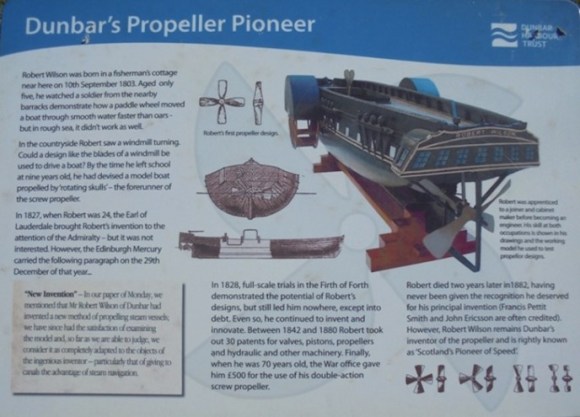

In the summer of 1827, whilst still overseer of the canal, Thomas Wilson visited his home town of Dunbar in East Lothian. Whilst there, he met with Robert Wilson, who was, presumably, a relative. Robert had been experimenting for some time with the idea of a scull or screw propeller for ships similar to those which were widely adopted twenty five years later. He had been having great difficulty getting the establishment to accept the designs and showed Thomas a beautifully worked model which he had made the year before. This wooden model was about 3ft long and contained a clockwork mechanism which could turn the working parts. It could be used to power either the side paddles or a stern propeller. Thomas was obviously impressed and prevailed upon Robert to loan him the model so that he could test it at Tophill and then demonstrate it to his employers – the Forth and Clyde Canal Company. Recalling the event in 1864, Thomas wrote:

“Being aware that the chief objection to the first side-wheeled steamboat, built by Mr Symington in 1801, was the impression that the side-paddles caused too much surge and injured the banks, on taking the model home, and having made the trial I found the greatest speed was produced by the side-paddles when there was no surge, but when the water was not smooth, the stern-propeller produced fully a little more speed, and caused very little swell.”

He promised Robert that he would recommend the adoption of the stern screw propeller for use on the Forth and Clyde Canal and suggested that the Vulcan could be converted for this purpose. If all went well Robert Wilson would be employed to produce the working plans for this project. Thomas Wilson provided two accounts of what took place late that year, or early 1828. In 1864 he wrote that

Being convinced that boats of this description were the most likely for canal traders, I took the model to Port Dundas [the terminal canal basin in Glasgow], where it was exhibited in presence of the late Kirkman Findlay Esq, Governor, and a few other Directors, who appeared satisfied that it was a great improvement. One of them, however, seemed to hold by the old system – that no machinery could be made to supersede the horse power for tracking vessels on the canal with greater safety and less expense.”

His 1860 version is also worth repeating:

“All the Gentlemen present appeared well pleased with the invention and passed high encomiums upon the inventor, and signified their intention to take the matter seriously into consideration. A few weeks after the above experiments I met the Governor and again suggested the benefit to the Company likely to be derived by having the Vulcan passage boat – the first iron boat on record – fitted up with Mr Wilson’s apparatus. His reply, however, was to the effect that the failure of the first paddle steamers on the Canal (fit up by Mr Symington), the Committee were not convinced that the stern power would give greater facility or cause less injury to the canal banks.” “My suggestion was therefore deferred to another period, and I am sorry to say there is not one of those gentlemen now in life to witness the number of steam lighters trading on the canal on the principle then proposed.”

Amazingly the beautiful model ship, suitably named the Robert Wilson, still survives and is now in the collections of the National Museum of Scotland (accession number T.1955.11).

The episode may not have been so perfunctory as it first appears, for on 10 July 1829 the Liverpool Mercury, which had been closely following this latest canal technology, reported the preparations to adapt the infrastructure for the new craft:

.“the canal is now in a great state of forwardness in Scotland, on the Forth and Clyde navigation from Glasgow to Grangemouth, where flag-stones are now laying down along the banks, preparatory to the introduction of steam navigation. The canal is about 24 miles long, so that experiment will be on a large scale. The flags are found in the immediate neighbourhood, and the most sanguine and well-founded expectations of entire success are entertained. Mr Morris says that the flagging is found so effective a preventive of the waste of the banks, that the proprietors of the navigation where the experiment is going forward are of opinion that the process will be economical in the end, even were steamboats not employed.”

The eyes of the managers of canals throughout Britain were on the leading role played by the Forth and Clyde Canal. However, neither the changes in the boats nor the infrastructure were actually executed. To be fair, the Admiralty also rejected Wilson’s screw propeller in 1833.

In July 1828 the Forth and Clyde Canal Company considered another proposal for the introduction of steamboats on the canal. This emanated from Thomas Grahame who was on the Council of the Company. He hired a small paddle steamer called the Cupid from David Napier. Her size, only 58ft long and 11ft in beam, meant that even though she was a side-paddler, she comfortably fitted the locks of the Forth and Clyde Canal. She demonstrated that she could tow passage boats at 5-6 miles an hour more cheaply and efficiently than could horses. The wash from her wheel was not significant and so the ban on steamboats was temporarily lifted (Bowman 1991, 38). A set of regulations was drawn up for the conduct of steamers on the canal – speed was to be limited to 5mph and steamers were to slow down when passing sail or horse-drawn vessels and to go offside of them. An advert was placed in the newspapers in 1829 to invite steamship owners to trade on the canal but none took it up.

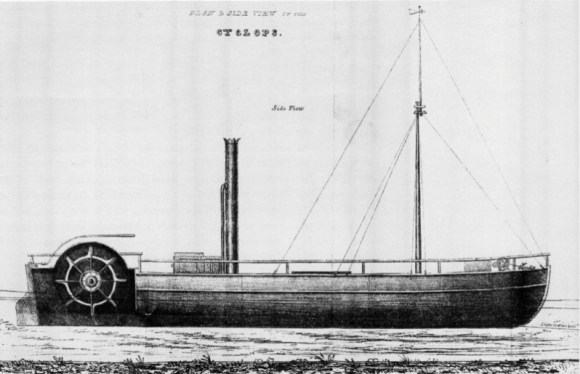

That October the Inspector of Works pointed out that “dispatch” was “everywhere the order of the day in conveying either goods or passengers,” and again suggested the lining of the banks with stones as mentioned in the previous paragraph (Lindsay 1968, 41). In 1829 it was agreed that John Neilson would adapt the Cyclops iron passage boat for steam power at his boatyard in Hamiltonhill in accordance with plans Grahame had procured from New Orleans – the steam engine and stern paddle were not significantly different to those of the Charlotte Dundas. The Cyclops had been built in 1825 at Tophill with a narrow beam for use as a fast passenger boat but was not a success in that role. She was widened and in September 1830 was fitted with a 15hp engine and a stern wheel at a cost of around £2,000.

The reconstructed boat is often described as the first steamer built for the canal carrying-trade as she was principally a goods vessel with capacity to carry 15 passengers. She made her first voyage from Grangemouth to Alloa and back to Port Dundas that autumn. However, it was soon found that the wash was indeed causing damage to the canal banks. By the late 1830s she was being used as a tug outside the canal at Grangemouth (see Wilson’s Log for her day to day duties).

In the meantime Thomas Grahame had also been experimenting with less heavy and swifter boats drawn by horses. In April 1830 an 8-man competition rowing boat was successfully tested on the Glasgow, Paisley and Ardrossan Canal as a horse-drawn canal boat. The streamlined “gig” construction was much speedier through the water than conventional canal track boats but was found not to be stable at the speeds required. To counteract this Grahame lashed two of the gig-boats together and tested the composite boat with horses on the wider Forth and Clyde Canal. It was so successful that he then had a vessel built of wood to this design at his own expense. It was 60ft long and fitted to carry 50-60 passengers. Again, it was tried out on the Forth and Clyde Canal and on 7 July made the journey from Port Dundas in Glasgow to Port Hopetoun in Edinburgh in 7 hours 14 minutes, returning the following day in 6 hours 38 minutes. This was considerably less time than previously taken and it was sufficient for the Canal Company to agree to purchase it. It was known as the Swift, which name thereafter became a generic term for these improved passenger boats on the canal. In December 1830 it was announced that the Swift “having been built of timber and intended merely as an experimental boat” was not sufficiently strong to resist the ice upon the canals and that consequently the service would be discontinued over the winter. This gave the Canal Company time to have iron replacements built at Glasgow and Tophill. The latter, supervised by Thomas Wilson, was called the Rapid, and commenced service between Lock 16 and Port Dundas on 4 April 1831, doing the journey in little more than three hours. She was described in the Glasgow Courier in glowing terms:

“A new passage-boat, called the Rapid, has been started on the Forth and Clyde Canal, which, for lightness, elegance and quickness of despatch, surpasses any that has yet been attempted on that Canal. It plies between Port-Dundas and Lock No. 16, and accomplishes the distance, 24½ miles, in little more than three hours, being at the rate of eight miles an hour. The boat, which is of the gig construction – the hull made of sheet iron – and drawn by two horses, is sixty-eight feet long, by about 6½ feet broad, and weighs about two tons, twelve hundred weight. There is accommodation for 50 passengers, and the interior is fitted up in a very neat and comfortable manner. At the forepart of the vessel it draws only nine inches of water, and at the stern twelve inches. When seen in the water it has a very light and elegant appearance.”

(Glasgow Courier 12 April 1831).

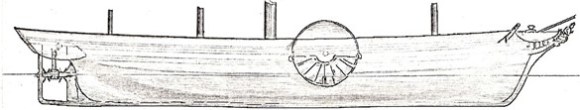

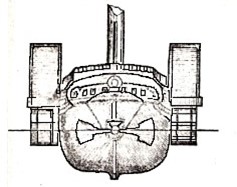

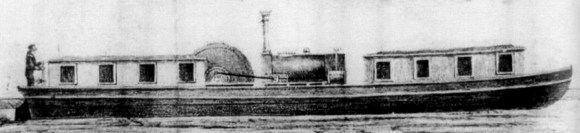

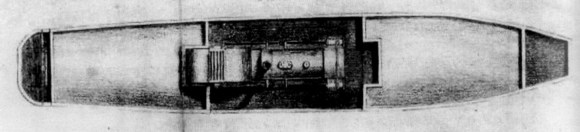

The catamaran boats provided another opportunity to reconsider steam power as it was believed that by placing the paddle wheel in the confined space between the two hulls it would reduce the wash. It was decided to upgrade the design to include steam power in order to provide an increase in speed, making them more competitive with the fast stage coaches then in operation. An order was therefore placed with Fairburn and Lillie of Manchester. William Fairburn was one of the leading steamboat designers of the period. In March 1831 Grahame went down to Manchester to witness the trial of this boat which had been named the Lord Dundas, a name evidently intended to recognise her heritage. On his return he reported that in England there was a “universal outcry in favour of railways” and that many businessmen were confident “that in time they must supplant all canal communication” (Lindsay 1968, 42). The competition in the future would be railway trains and not stagecoaches. Lord Dundas had an engine on the locomotive principle, of 10 hp, set amidships, with a direct drive to a single paddle wheel placed between the hulls just aft of the engine. Water was to be drawn to the wheel through the gap between the hulls. The position of the engine meant that she had two separate passenger cabins – one ahead and one astern of the engine. The dimensions of this boat were as follows:

| Whole length | 68 ft |

| Breadth | 11ft 6ins |

| Depth | 4ft 6ins |

| Width of tunnel or wheel-trough | 3ft 10ins |

| Diameter of paddle-wheel | 8ft 6ins |

The entire weight of the hull of the boat was about 2 tons 14cwt, while the weight of the boiler, (which for security was made nearly double the strength of those used in similar engines on the railway) with the engine, wheel, fittings, water in the boiler, &c. added upwards of six tons, making a total weight of a little over nine tons. When floating without the engine and machinery, the average draught of water was 8½ inches; with the boiler filled, and her engine, coals, and machinery, the average draught was increased to 19½ inches. Her trials took place on the Mersey and Irwell Navigation over a measured mile when she achieved a speed of just under 9mph on the sinuous course. In describing her, the Glasgow Herald stated that

“the Lord Dundas is admirably calculated for navigating canals, as the whole action of her engine is in the middle or deep part of the canal, and the water is perfectly free from agitation at the banks on either side.”

Clearly the hulls were containing the disturbance, and the “great friction in the tunnel” limited her top speed. It may also have led to cavitation on the floats. The trials showed that she performed better with coal than coke, and that she was very economical with the rate of its consumption.

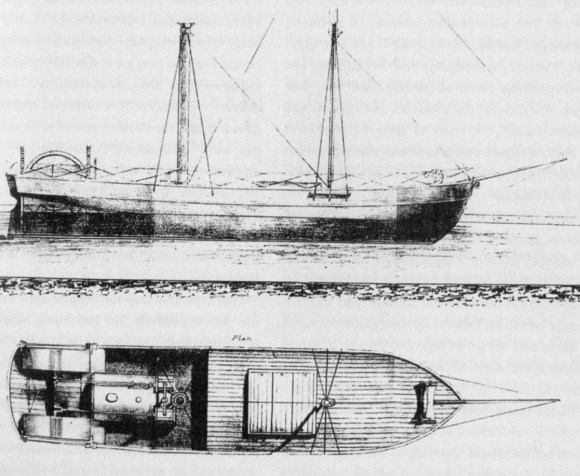

Twelve months later Fairburn and Lillie delivered another steamboat, the Manchester, to the Forth and Clyde Canal where she was fitted out for her new role. Shortly after her arrival she was sighted by an excited correspondent of the Caledonian Mercury:

“We were not a little surprised at the appearance of an iron steam vessel entering the port of Leith with a heavily laden sloop in tow; on inquiry we learned that this vessel is one lately built at Manchester, by Messrs Fairbairn and Lilly, for the luggage and goods trade of the Forth and Clyde Canal. She came down from Grangemouth to Leith in three hours, and will make the voyage from Leith to Port Dundas in about ten hours, or about one-fourth of the time which the Railway Company, or one half of the time which the Shipping Company say is occupied by this voyage. The steam vessel in question came down from Liverpool to the Clyde in the stormiest week of this winter, and has proved herself a most seaworthy vessel. The engine and machinery are placed behind, so as to prevent all interference with the Canal banks and locks, and she makes no side wave. We understand a steam light goods and passenger boat, on the same principle, is in progress of being completed, and will be in readiness to ply on the Union Canal in two months, and that she is intended to ply between Port Hopetoun and Port Dundas.”

(Caledonian Mercury 23 February 1832, 3).

She was sent on a trial voyage to Dundee on 23 April and performed very well. On the way back the fireman, being accustomed to sailing on the canal, developed sea sickness in a heavy swell and allowed the steam to go down, slowing her passage. She commenced service on the goods trade between Port Dundas and Grangemouth and then on to Stirling on 26 April 1832. The Manchester was a more conventional vessel than the Lord Dundas, with two paddle wheels at the stern – an improved version of the Cyclops. Side paddles were not suitable for canals with locks. It was not a good time to introduce a new passenger vessel on the canal – cholera had just broken out in Kirkintilloch. In any case, she was intended to concentrate on heavy cargoes of up to 50 tons between Glasgow and Stirling, Alloa, and the east coast ports around the mouth of the Firth of Forth. For this role she was given extra equipment at Tophill at a cost of £170:

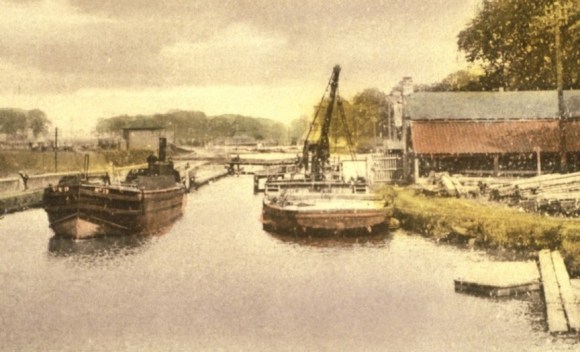

“The Manchester draws, when fully loaded, between five and six feet of water; and carried, in the voyage to Dundee, a heavy iron crane, capable of raising a weight of four or five tons, erected on one side of her deck, for the purpose of facilitating the reception and delivery of goods at the various small ports in the upper pats of the Firth of Forth. The effect of this heavy erection on one side of the vessel caused a want of steadiness in the seaway, which might be avoided in a vessel plying to Dundee where there is no want of cranes.”

(The Globe 1 May 1832, 1).

An interesting proposal was put forward at the time that the Manchester was introduced on to the Forth and Clyde Canal:

“If the Canal Company would put on an additional set of gates at the end of each lock next the lower reach, the canal steamers might be made from 15 to 18 feet longer than at present. The expense would be trifling, as it would consist solely of these additional gates at one end of each lock. The present lock gates are worked by a long lever on the old system; and, of course, to enable the lock-keeper to work the lever, the stone work of the lock extends far beyond the present gates, to the point where the additional gates might be placed, if they were to be wrought by a wheel. The additional length which might be given to the locks by this means, and the consequent addition to the length of the vessels passing though the locks, would greatly increase the stowage of these vessels, or give excellent accommodation to passengers; and, as experience in steam vessels has demonstrated, would considerably increase their speed.”

(The Globe 1 May 1832, 1).

The Manchester ran the goods service between Port Dundas and Stirling until 1837. She had a major refit in 1835 at Alloa where McAllister and Martin had “the paddle wheels placed amidships” (Mitchell & Ronald 2007, 85). During the construction of the new dock at Grangemouth in 1839 she had her engine removed and was used to carry lime from Charlestown. The engine was used to pump water out of the excavation for the dock (see Wilson’s Log).

After a couple of years in which the Lord Dundas was used mainly as a tug for passage boats, she was converted for use in yet another experiment. A chain was laid along the bottom section of the canal and was led over a wheel placed between her hulls; the engine turned the wheel by which means she was pulled along. The design was doomed to failure. In 1836 Lord Dundas also had her engine removed and she was turned into a barrack boat for canal workers (Bowman 1991, 38).

Another canal steamer, the Edinburgh, built by Wilson at Tophill, commenced the night service between Port Hopetoun in Edinburgh and Port Dundas in Glasgow on 28 September 1832, along with the horse-drawn swift boat Velocity. The Edinburgh carried six tons of goods and 40-50 passengers. She was propelled with two high pressure engines of seven horse power each, at the rate of six miles an hour. The machinery was placed amidships, and the paddle wheels at the stern; the 16ft long space in between being occupied as a cabin for the steerage passengers. The hold for the goods and principal cabin were in the fore part of the vessel. She was leased to the London Leith Edinburgh and Glasgow Shipping Company for operational use. It is surprising that this vessel, which was built at Tophill with the Edinburgh service in mind, was found after just a few months to be unsuitable for the Union Canal and was withdrawn. She was returned to the Canal Company and taken back to Tophill where she was converted for use as a tug in Grangemouth harbour where she gave many years valuable service, latterly with side paddles.

This was an exciting time for boat design on the Forth and Clyde Canal in both the horse-drawn vessels and those powered by steam. There were great advances being made in streamlining the hulls, in reducing the overall weight of the vessels and thus the draught, and the use of new materials. Steam engines, boilers, and propulsion systems were also greatly advanced. Although much of the work was empirical, academics like John Robison RSE took an interest in the experiments. In December 1832 he presented a paper to the Society of Arts for Scotland “on his experiments on the Forth and Clyde Canal with a view of ascertaining the comparative resistance of certain forms of vessels when tracked at varied velocities” and was awarded an honorary medal by that Society.

In 1836 John Neilson built the Vesta, a paddle tug, for the Canal Company for use at Grangemouth, where she ran successfully and profitably (see Wilson’s Log). 1836 was also the year that Thomas Wilson’s son, also called Robert, took a lease of a new yard at Port Downie and most of the business from Tophill was transferred to it. It had a dry dock and a patent slip and was far more suited to the work. He continued his father’s approach of installing the latest technology and design, but it was to be another 20 years before the screw propeller was to form part of an iron lighter launched there.

Two packet tugs with paddle wheels were run from Port Dundas to Greenock in the early 1840s. These were the Prince of Wales and the Experiment. The Gipsy was also in use for a short spell before being sold in 1843 and became the first steamboat on Loch Katrine. Her appearance there was bitterly opposed by the local boatmen and she mysteriously disappeared (Bowman 1991, 39).

The application of locomotive power to tow vessels from the canal towpath has been dealt with in a separate article. Extensive experiments were conducted on the canal to the west of Lock 16 on the Forth and Clyde Canal in 1839, led by John Macneill the consulting civil engineer for the canal. They were witnessed by Thomas Wilson (Locomotive power applied to canal transit).

In any case, there was a much more practical alternative than building a railway to compete with a railway, and that was to develop the motive power of the boats themselves in a manner which minimised the erosive effects of any wash. One local man even experimented with a prototype of a pump-jet, as noted in this newspaper report from the Evening Mail on 13 July 1840:

“An ingenious mechanic, residing at Grahamston, has been for a long period engaged in constructing a small vessel to be propelled by means of pressure pumps – the application of a principle quite new to the masters of this science. On Monday evening the boat was launched into the Forth and Clyde Canal, at Bainsford bridge, and proceeded beautifully along the reach at a rate of not less than 15 miles per hour, conducted alone by the inventor, who worked the pumps. This novel invention has produced much speculation among the members of the profession at this place, and it is now reported that he is so much satisfied with his first experiment, that another on a larger scale is forthwith to be undertaken, and a patent procured to protect the invention. He has no doubt that it will, at no distant era, entirely supersede the present mode of propulsion by means of a paddle wheels.”

Essentially, the device worked by taking in water from the navigable channel through an intake valve and then increasing its pressure using a pump and forcing it backwards through a nozzle. The principle of a water-jet to propel a boat had already been demonstrated by James Rumsey on the Potomac River in America in 1787 using a steam-powered pump to drive a stream of water from the stern. Unfortunately, the newspaper article above does not name the “ingenious mechanic” of Grahamston and the mechanism was not developed at that time.

Engineers again turned to the screw propeller and numerous experiments were conducted throughout the world in how to fit it to existing vessels. In many of these early experiments the devices were not an integral part of the ship’s design and were temporarily added to existing vessels, making them less efficient than they should have been. The propelling unit was tried in various positions – behind, in front of and below the vessels. The latter was tried out on the canals in our area in 1840.

“CANAL NAVIGATION. On Wednesday [2nd] a trial was made on the Paisley Canal, of a steam-boat propelled on the principle of the screw. It turned out a failure, however, in consequence of the want of water. It appears that the propelling spindle was placed beneath the bottom of the boat, and extended downwards about 25 inches; the depth of water was not sufficient for a boat so constructed, the blades of the propeller striking against the ground. A trial is to be made on the Forth and Clyde Canal, where there is a greater depth of water.”

(Liverpool Standard 4 September 1840, 3).

And so the boat was taken to the same test area west of Lock 16 which had played host to the locomotive trials the year before in 1839.

“As we stated in the Advertiser of the 19th ult, the experimental steamer, at present on the Forth and Clyde Canal, was docked for the purpose of making certain alterations on the propeller. On the former occasion the floats [blades] were fixed at an angle of 45 degrees to the shaft of the propeller, which gave of course a progressive motion of six feet in each revolution, the diameter of the propeller being two feet. On the present occasion the two floats were placed on the shaft at a more obtuse angle, so as to reduce the progressive motion from six to four feet. On Friday week, in presence of Mr W. Houstoun, of Johnstone Castle, Mr Johnston, of the Forth and Clyde Canal, Mr Ellis, of the Union Canal, and a number of strangers from a distance, interested in the result, the boat was got under weigh from Lock 16. To conduct to a satisfactory conclusion, of course, the pressure of steam in the boiler was made the same as on the first experiments, viz 54 lbs on the square inch; and the result of this change in the angle of the floats to the shaft, was found to be an acceleration of speed of 20 per cent, or rather more, as compared with the first experiments. That is, when the floats were placed at an angle of 45 degrees upon the shaft, the speed was found to be five miles an hour; now, when the angle is rendered more obtuse so as to produce four feet progressive motion, it is found that the speed was at the rate of six miles an hour. The result was extremely satisfactory to all the gentlemen present, confirming, as it did, their former anticipations; and the boat has again been laid up preparatory to other alterations which are contemplated, in order, experimentally, to demonstrate the most efficient angle at which the floats should be placed upon the propelling shaft.”

(The Globe 15 October 1840, 3).

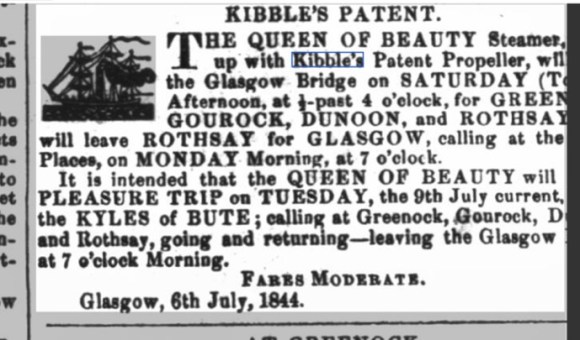

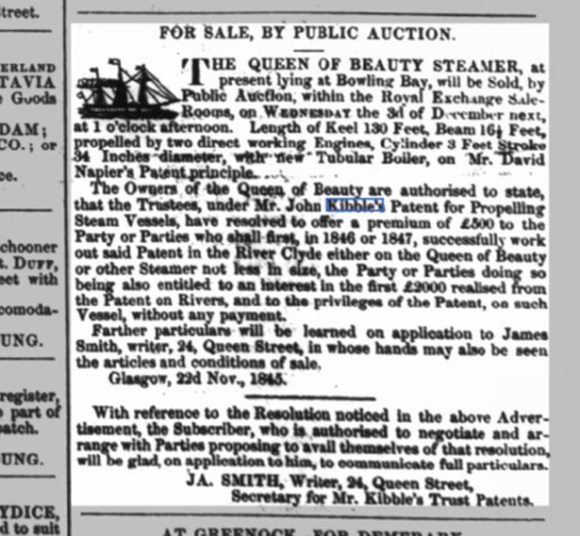

In parallel with these experiments, trials were being conducted using alternative forms of steam propulsion. In the early 1840s John Kibble of Paisley examined the conventional paddle wheel used on boats and realised that the circular shape limited the time that the paddle blades (known as floats or buckets) were in the water providing thrust. If the “wheel” could be made oval and fixed with its long axis lying horizontal it would be more efficient. He came up with the idea of using an endless belt with floats attached over wheels set at the sides or stern of a ship – the Kibble Patent Propeller. He tested the design on models before conducting experiments with a boat on the Paisley Canal. This may have been the Merlin. Representatives from both the Forth and Clyde and the Union Canals witnessed the trials and considered that the results merited further work on their own canals (Paterson 2006). Meanwhile an experimental steamship was constructed by Thomas Wingate & Co for the patent trust (established by a few investors from Glasgow) specifically for this form of propulsion and called the Queen of Beauty.

She had two drums on each side with an iron chain which turned on them by friction; the chain was studded with floats so that about twenty floats on each side had a direct propelling action in the water instead of only two or three as on the common paddle-wheel. She was tried over the summer of 1844, running between Greenock and Glasgow.

Unfortunately, the small size of the boiler limited her power. Even so, on her second trials she performed the trip in 1 hour 34 minutes, returning against the tide in 2 hours 15 minutes – equal to other steamers of the period (Glasgow Courier 29 June 1844, 4). Having proved her worth she was then used over the remainder of the season for pleasure trips to the Kyles of Bute.

Robert Wilson of Tophill seems to have been involved in the early experiments with the Kibble Patent Propeller on the Forth and Clyde Canal. He then conducted his own tests and made a model for the Council of the Canal Company to examine. Its members must have been keen to know if the wash was going to be a problem for the banks of the canal. Kibble gave his permission to use his patent in May 1844. Wilson’s design and model were accepted and it is probable that he oversaw the construction of the boat at Port Downie in 1844 (Bowman unpublished). The vessel, known as the Fire Fly, was owned by the Forth and Clyde Canal Company. It was intended to act as a tug, towing the passenger boats. At first things went very well, to such an extent that the Press was confident that it represented the way forward:

“We are glad to learn that Steam-navigation is now applied to Canals with perfect success; a small steamer with Kibble’s Patent being at present regularly plying on the Forth and Clyde Canal, dragging swift passage-boats at a speed equal to that of horses. This patent consists of a pair of wheels at each side of the vessel, having an endless chain over each pair, with floats attached. These are put in motion by a shaft from the engine, the chains going round by the friction-hold they have on the wheels surface. We understand that considerable improvements will be made on the construction of future steamers to give still a greater speed by this patent – but the present boat as it is, will, we are informed, drag more, with about half the power and at a greater speed, than can be done on the screw principle – and creates no surge whatever to injure the banks. Considering the very great saving and other advantages in using steam-power in place of horses. it is believed by those competent to judge, that Kibble’s patent will soon be in general use on all Canals.”

(Glasgow Citizen 1 February 1845, 2).

There was one noticeable problem. At Shirva, east of Kirkintilloch, it was found that the horses using the Statute Labour road which ran alongside of the canal were startled by the noise of the steam-boat. This was considered to be a somewhat trivial matter and if the boat performed well it would be overlooked. It did so:

“We may state, that we are much gratified, lately, in seeing a small steamer on the same principle, called the “Fire Fly,” plying on the Forth and Clyde Canal. It appeared admirably adapted for canals, there being no surge whatever from the paddles, and the paddle-boxes being only about a foot wide on each side of the vessel. We are informed that, when this vessel has sailed without towing, her speed at times has reached 8 1/3 miles per hour, which had never before been attained on this canal with any amount of steam power whatever. This little vessel is well worthy the attention of those interested in canal navigation; she is the property of the Canal Company, and is daily plying from Port Dundas. This being the first boat built on this principle for canal sailing, its success is the best guarantee that it will soon come into general use; and experience, we doubt not, will suggest many improvements, by which a still greater speed will be obtained.”

(Glasgow Herald 3 March 1845, 4)

Although the right to run passengers by the canal, between Glasgow and Edinburgh, was purchased by the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway Company, the Forth and Clyde Canal Company continued to run the swift boats between Glasgow and Castlecary, a distance of 20 miles, much to the satisfaction and convenience of a large number of passengers. Indeed, it was now carrying more passengers than ever. Coaches on the improved roads at either end of the trip then continued the journeys. Part of the reason for this continued success was that the railway fares for short-distance travel between stations were extravagantly high. The railway company then reduced their fares and a price war ensued. The railways won. As soon as the swift boat was out of the way, and the horses sold off, the railway fares were increased to the old rates. When the swifts were discontinued in March 1848, Fire Fly had her engine and propelling machinery removed and was used as a pay boat (Bowman 1991, 39)

Meanwhile, the Queen of Beauty had been laid up at the Broomielaw in Glasgow over the winter of 1844/45 so that a new boiler could be fitted. The method of securing the floats was also changed in order to improve their reliability. This certainly enhanced her performance, and her usual rate of sailing in the 1845 season from Glasgow to Greenock, with favourable tides, varied from 1 hour 31 minutes to 1 hour 34 minutes; and with adverse tides, two hours. There remained technical difficulties with the Kibble propeller and so she was soon converted to house conventional paddle wheels. Today John Kibble is best remembered for his conservatory which now stands in the Glasgow Botanic Gardens.

Not all of the hopes of the canals were placed into the Kibble Propeller. Back in August 1840 it had been announced that screw propellers were to be placed on the Forth and Clyde Canal (Manchester Times 15 August 1840, 3). However, it was June 1844 before two steam tugs with screw propellers were successfully introduced to the Union Canal.

They were built of iron by John Reid & Co, Port Glasgow; and the upright engines, screw propellers, and machinery were fitted up by William Napier senior, Glasgow. The engines communicated their power to the screws placed on each side of the bow by an arrangement of wheels with wooden and iron teeth in order to prevent noise and vibration. This was a collaborative project between the Union and the Forth and Clyde Canal Companies. An experiment with one of these steamers took place that month under the superintendence of the Union Canal Company’s manager, Robert Ellis, in the presence of its chairman, Col. McDonald, and some of the directors – Messrs Maxwell, MacLagan, Burns, L’Amy, and Tennant. Mr. Shaw, manager for the Duke of Hamilton; Mr. Crichton, manager of Forth and Clyde Canal; Mr. Glennie, manager of the Monkland Canal; Captain Yuill of the Royal Navy, together with a number of other gentlemen were also present. The tug was driven at speed without creating any of that surge or wash on the banks which had hitherto formed the chief objection to the use of steamers on the canals. The steam-boat had attached to her six very large scows deeply laden, but she was considered capable of towing double the number without material diminution of speed. The tracked scows were connected together by rods having a parallel movement, all under the control of the steersman on board the steamer, so that the necessity of a separate rudder and steersman for each scow was avoided. The whole train moved along with a steady and uniform motion (Glasgow Citizen 15 June 1844, 2).

One of the Union Canal’s tugs was used by the Forth and Clyde Canal Company (see Wilson’s Log 8 July 1844) for further tests which were supervised by Mr Glennie. On 19 July 1844 a train of barges, or scows, nearly 800 feet in length and carrying a gross weight of about 700 tons, was attached to the tug, and towed along at the rate of 2½ miles an hour. The route taken was from Port Dundas to the Bowling Junction. The train was steered with great care, and on its return passed up through the harbour at Port Dundas, and cleared the narrow bridge, which has a very acute turn, without touching on either side. The experiment on this occasion was witnessed by the following, among other gentlemen: George Readman of the Forth and Clyde canal, Robert Ellis and Peter B Henderson of the Union Canal, William Napier, John Wood, Mr Home, and Mr Wilson. A small high pressure boiler was sent from Grangemouth to Port Dundas for a vessel being built at Paisley “as a tug for tracking the passage Boats” (Wilson’s Log 5 July 1844). Strangely, no more is heard of the screw propeller on the Forth and Clyde Canal until 1856.

It was evident to many businesses that although steam powered ships were flourishing beyond the confines of inland waterways, it would take some time for them to infiltrate the canal. Horse-drawn vessels such as dumb lighters and scows would be required for some time. Sail too, such as schooners, sloops, smacks, and brigs remained in use. Throughout the 1840s they continued to be built in the local yards. There were a number of private firms producing such vessels. David Swan, based at the Blackhill Locks on the Monkland Canal, was a speculative builder of scows of 60-63 tons burthen. Most vessels were built to order by the likes of Napier and in 1851 Thomas Adamson took over the boatyard at Port Downie for the building of scows. The Forth and Clyde Canal Company itself invested in more and more such vessels. In 1847 it commissioned eight iron schooners from William Napier junior at the New Quay, Hyde Park, Broomielaw in Glasgow. Their dimensions were 65 feet long, 18½ feet in the beam, and 160 tons burthen. Ten more were constructed for the Canal Company at Lancefield Quay, Finnieston, by Napier and Crichton in 1850. Iron was replacing wood.

In 1854 the Carron Company acquired its first steam vessel, a small paddle tug steamer called the Rob Roy which had been built 17 years earlier (Somner 2000, 165). She had been used at Grangemouth Docks by James Robertson and William Adam. The Carron Company used her to tow lighters on the top level of the canal until 1871, when she was broken up (Bowman 1991, 39). Presumably she was able to conform to the regulations laid down by the Canal Company but passing through the locks slowed down any fast travelling boat.

For a few years there was no passenger service on the Forth and Clyde Canal until at length a private individual started one up. Alexander Taylor, farmer and proprietor of the Eagle Inn near Kirkintilloch, started to operate a boat between Port Dundas and Lock 20 at Castlecary. Taylor had previously been a postilion on the swift horses before moving on to hiring horses to the Canal Company and then acting as its ticket agent. In 1852 he was joined by James Taylor, a Falkirk ship-owner, and as A & J Taylor they extended the low price passenger service to Lock 16 using two horse-drawn boats.

In 1856 the Forth and Clyde Canal Company fitted a boiler and a simple two cylinder engine costing £320 to the Thomas, one of its 80 ton iron lighters. The task was given to James Milne, the resident engineer at Hamiltonhill. The engine drove a screw propeller. On trial in September 1856 a speed of 5 mph was achieved. This was 2 mph faster than the horse-drawn scow. Her three tons of machinery and water and a space for coal bunkers was accommodated in the five frame spaces at the aft end in an area not given over to cargo in the traditional scows. As a result her carrying capacity was scarcely impaired. Given the relative absence of wash she was considered a success. After the trial the Thomas worked for over a year between Port Dundas and Bowling and averaged three to four trips per week compared with the two of the horse-powered scow. She made 3 mph over the whole 12 mile voyage, including the time passing through the locks. She could travel 100 miles on one ton of coal. At first the Thomas had a crew of two but a third was later added to tend to the engine. As a horse-drawn scow Thomas had needed two boatmen, a horseman and, of course, the horse. There was thus a great economy in using steam power. By 1858 Thomas was plying between Port-Dundas and Greenock, carrying 60 tons of goods at the rate of 5 mph with ease, without doing the slightest injury to the canal banks. Carron Company reacted quickly to the presence of a screw steamer on the canal and by June 1857 it had two of its own conveying goods to and from Glasgow. They were about 80 tons burthen and possessed small oscillating high-pressure engines with three-blade screw propellers.

At the end of 1857 the Swan Brothers produced the first purpose-built screw lighter at the Kelvin Dock in Maryhill. The Glasgow was also built of iron. The engine exhaust was turned up through the funnel to help draughting. This produced a puffing noise which earned such vessels the nickname of “puffers.” Within a year a sugar company also had a steam barge in active operation.

Observing the success of the Thomas and the other steam barges, A & J Taylor thought of applying steam and the screw to their own swift boat. They first got a new swift boat built adapted for the screw. This was the Rockvilla Castle. The cylindrical boiler was only 2½ feet in diameter and stood vertically between the cabin door and the handle of the helm. The engine was bolted to the boiler, saving much frame work, with the cylinder uppermost so that the steam past direct from the top of the boiler into the valves, and the piston rod acted directly by crank on the axis of the screw propeller, which revolved below the boiler. The high-pressure engine provided 7 hp and it and the engine were enclosed in a small square wooden box. Given the innovatory nature of the work it is not surprising that it took several alterations before it ran successfully. A balance-wheel was placed on the axis of the screw and by September 1858 it was running at the rate of 7 mph. Further alterations improved this performance still further. In addition to low fares, the passengers were able to take advantage of being able to be picked up or dropped off at any place where the canal bank could be reached. The seats of the cabin were comfortably cushioned and could accommodate 60 passengers. The railway company immediately reduced its fares in the boat district. On 19 September 1859 James Henderson & Son launched the iron screw steam lighter Joanna from their building-yard in Renfrew, for plying on the Forth and Clyde Canal. She was acquired by the Forth and Clyde Canal Company which soon sold her to Thomas Rutherford, carrier and contractor, of Paisley for trading between the canal and the River Cart. The cost was £300 which was to be paid in monthly instalments. The vessel, however, did not perform well and Rutherford went bankrupt. Not having made the final payments Joanna was taken back by the Canal Company.

Thomas Wilson, now an old man, had kept a watchful eye upon developments.

“It is gratifying to note” he stated, “that Mr Wilson’s invention has at last taken root on the canals. And will be found, as formerly predicted, that the screw propeller will be found on inland navigation the most profitable for conveyance of goods and passengers. Mr Milne, the Canal Company’s Engineer, is worthy of all praise for his unwearied exertions to introduce screw propellers on the canal. Within these few years, numbers have been and are now fitting up by the Canal Company, Carron Company, and several others. The energetic Alex. Taylor has latterly fitted up another greatly improved screw passage boat, which plies daily between Lock No. 16 and Port Dundas. She is well patronised, and is found to cause little or no surge on the canal, so much dreaded in former days.”

In March 1859 his son, Robert Wilson, returned to the boatbuilding yard at Port Downie and announced that he was ready to receive orders for the building and repairing of wood and iron vessels for the Forth & Clyde, Monkland, and Union Canals (Falkirk Herald 10 March 1859, 2). The first iron screw lighter, the Henry of Netherwood, was duly launched on 3 July 1860. It was built for John Watson senior, coalmaster, Glasgow. She was equipped with a pair of high pressure engines with a horizontal tubular boiler by John Yule & Co of Hutchesontown, Glasgow. Thomas Wilson was present at the launch. Other innovations were introduced. Robert Wilson placed the rudder around the propeller of the Henry – the first time this had been done in central Scotland. Its unusual occurrence is well illustrated in the newspaper report:

“The peculiarity of the boat is that the propeller is placed outside of the stern post, thereby causing, of course, the rudder to travel round it. By this means fully two more feet of keel is obtained – a matter of the greatest consideration. We understand that the boat in question is the first of the kind to have a propeller of this description, on the canal. It was first thought that owing to the hole in the rudder, its sailing properties would be defective but since its trial all unfavourable impressions have been dissipated.”

(Falkirk Herald 21 June 1862).

The death of James Watson delayed the Henry going into service, but when she did so she was found to be one of the fastest vessels on the canal.

More iron screw lighters followed from the Port Downie yard. The Alice, named after the Queen’s second daughter, was launched on 3 July 1862. She was 66ft in length, 13½ft in breadth, 6ft in depth, with a carrying capacity of upwards of 70 tons drawing 5ft of water. She was engined by the Canal Basin Foundry Co, Port Dundas, with a pair of oscillating engines of 7ins diameter, with a vertical boiler of 4ft diameter. Although contracted for by Walter Wingate & Co, Shirva Colliery, she was bought from them by James Hay, boat owner, Port Dundas, even before she was launched (Falkirk Herald 10 July 1862, 2). Then, in the last days of 1862 the Mary of Bonnybridge was launched for George Turnbull of Bonnybridge Tile Works. It was 69ft long by 13ft 4ins in the beam, being 65 tons burthen. It was considered to be the strongest iron vessel on the canal since the Vulcan. Two more iron screw steamers were completed shortly afterwards for the Carron Company, one of which was of 100 tons.

| 1801 | Charlotte Dundas | |

| 1818 | Vulcan | 1873 |

| 1828 | Cupid | 1829 |

| 1829 | Cyclops | c1829 |

| 1830 | Swift | |

| 1831 | Lord Dundas | 1839 |

| 1832 | Manchester, Edinburgh | 1839 |

| 1840 | Merlin | |

| 1844 | Queen of Beauty | 1846 |

| 1845 | Fire Fly | 1849 |

| 1850 | Rob Roy | 1870 |

| 1857 | Thomas | |

| 1857 | Glasgow | |

| 1860 | Rockvilla Castle | 1881 |

By 1858, six lighters had been fitted with screw propellers; and by 1859 there were 18 such vessels in operation and at least 9 more being made ready. One of the boats introduced in that year was an ice-breaker, which was also used as a crane-boat; the engines and boiler for this cost £430. Engines costing £150 were then fitted in the mineral scows which had hitherto been worked by two boatmen, a horseman and a horse apiece; and the number of screw vessels working on the canal rose to 25 in 1860, 36 in 1862, 50 in 1864, and 70 in 1866 (Lindsay 1968, 46).

In 1862 John Rankine published a landmark book demonstrating that his grandfather, William Symington, should be credited with the first practical application of steam power to ships. William’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth, had married John Rankine whose family owned property in Rankine’s Lane, Falkirk (hence Rankine’s Hall). John Rankine junior lived in the Pleasance and was also an engineer, responsible for the town’s two fire engines. At the Port Downie boatyard he got access to the remains of the Charlotte Dundas which had been bought from the Canal Company by Robert Wilson in 1860 in order to make commemorative articles from her for sale. Using the wreck, and with advice from Robert Wilson, he was able to make an accurate model of the hull. He claimed that he had in his possession some of Symington’s original drawings of the machinery (that seems unlikely as no “original” drawings have survived. In 1828 William Symington prepared a coloured drawing at Falkirk which was kept by his son William, from which his son produced an etching published in Mechanics’ Magazine in 1833. Rankine may have known of this drawing but he depicted a version in his publication which differed in several respects and which shows the machinery as represented in his 1862 model) and spoke to eye witnesses in order to refine the mechanical aspects of the vessel. David Napier, also a keen promoter of Symington’s claim, provided advice. He was one of the first marine engine makers in the world and had been on the Charlotte Dundas several times. John Rankine’s son, W. H. Rankine, also an engineer, then placed it on show in the Great Exhibition of that year in London. It was subsequently exhibited in the Science Museum there, and at the 1888 Glasgow International Exhibition, going to the Exposition Universelle in Paris the following year. It is now in Australia.

Using information provided by James Milne, Rankine wrote that

“any fault or objection to the steam-boat of 1801 was, that she was too fast, which caused the then directors of the Forth and Clyde Canal to prohibit her from working, as they thought she would injure the canal banks. She was, therefore, laid aside in 1803, and there were no steam-boats used on the canal, their birthplace, until 1826, when various plans of propulsion were tried. But none seemed to give any hope of success until the year 1856, when the screw propeller was adopted, the use of which is now extremely common. No less than 34 screw steamers since that year have been launched in the Canal.

- 1 passenger boat

- 1 ice breaker

- 2 goods boats, carrying from 30 to 40 tons.

- 12 mineral scows, carrying from 55 to 65 tons.

- 11 lighters, carrying from 70 to 85 tons.

- 7 lighters, carrying from 100 to 120 tons.

The first of the above craft (the ‘Thomas’), was put to work with engine-power in September 1856 – has worked satisfactorily since that time, and continues to do so”

(1862, 79).

John Rankine was also interested in boat design:

“Falkirk is the birth-place of steam navigation, and from an experiment made on Friday near Lock 16 of the Forth and Clyde Canal, we are satisfied Falkirk will have the honour of completing what was so well begun by the illustrious Symington . Our townsman Mr Rankine, a grandson of Symington, having conceived the idea of dispensing with the rudders of ships, and thereby preventing the fearful annual loss sustained by the loss of such, applied his invention on Friday to a ten feet ordinary small boat – by no means a favourable mode of testing the value of the invention, seeing that the apparatus had to be of the flimsiest and most primitive character. Mr Rankine, however, was so certain of the capabilities of his invention that he risked his first practical experiment before 40 or 50 gentlemen, in the small boat referred to. This, we have pleasure in stating, was successful in the highest degree.

The little boat answered the new steering apparatus with the utmost fidelity, turning with greater rapidity and precision than it were possible for a similar boat propelled and steered by the old system to have done. The great beauty of Mr Rankine’s invention is its simplicity – being merely a happy application of every-day practised mechanism. For obvious reasons we forbear entering into details in the meantime.”

(Falkirk Herald 6 February 1862, 4).

Unfortunately no description of Rankine’s invention was given but it seems likely that it followed upon Wilson’s work at Port Downie. Rankine was intimately connected with that boatyard and in 1863 he was responsible for the design of a new type of slip for launching its vessels which used a steam-powered winch (Falkirk Herald 28 May 1863). John Rankine continued to take an interest in ship design and in 1870 submitted two models for a competition to design a channel steamer arranged by the Society of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce. One of his models was for a catamaran. Out of the seventeen models submitted his came first and second, but were not adopted (Falkirk Herald 16 April 1870, 2).

The design of screw boats for use on the Forth and Clyde Canal developed in its own unique way and the Thomas is often seen as the first of a new breed which became known as puffers. Ten years after the Thomas experiment there were 70 puffers employed on the canal. As steam was available to drive a winch they were usually fitted with a mast and derrick. These were for use on the canal and were known as “inside boats.” The story of their evolution may be found in Paterson’s book (2006). Some of the owners had interests in coastal trade as well and so between the 1870s and the 1890s a sea-going version was developed as “outside boats.” These were made famous by the stories of the Vital Spark and its skipper, Para Handy. By 1907 there were about 160 steam lighters and about 170 self-propelled vessels (ie dumb scows, lighters, barges and other sailing vessels) on the canal. Slowly the proportions changed and the overall number of vessels decreased.

| YEAR | NAME | BUILDER | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1866 | No. 7 | Thomas Adamson & Co, Grangemouth. | |

| 1871 | No. 9 | Barclay, Curle & Co, Glasgow. | |

| 1871 | No. 10 | Barclay, Curle & Co, Glasgow. | |

| 1878 | No. 12 | H. Murray & Co, Port Glasgow. | cost £1,280. |

| 1878 | No. 13 | H. Murray & Co, Port Glasgow. | cost £1,280. |

| 1905 | No.10(2) | J. Cran & Co, Leith. | |

| 1906 | No. 8(2) | Lawrence Hill & Co, Port Glasgow | Built in 1866, bought by Carron Co 1906. |

The Rockvilla Castle was the last boat to operate a place-to-place all-the-year-round public passenger service on the canal. Later steamers operated summer pleasure excursions only. A few years after its introduction the Rockvilla Castle was purchased by George Aitken but when he drowned in April 1880, having fallen overboard at Cadder, she was sold to Mr Glover of Paisley. She only operated for another year and finally left the canal on 24 September 1881 to be broken up at Paisley (Martin 1977, 19).

The number of scows, barges, lighters, and other sailing vessels, i.e. vessels not self-propelled, using the Canal in the year 1926 was about 70, and of steam lighters about 70 (the same as in 1866). The whole of the 70 non-propelling vessels did not use the Canal daily – some of them were occasionally laid up and were used as the traffic required. In regard to the self-propelling vessels, these were not all regularly on the Canal. They traded beyond the Canal – to ports and places on the Firth of Clyde, West Highlands, and the East Coast of Scotland, and also to Ireland. The speed of vessels on the Canal in 1926 had not increased over previous decades and was as follows:

- For non-propelling boats on the level part of the Canal, an average speed of 3 miles per hour.

- For self-propelling boats on the same portion of the Canal, an average speed of 5 miles per hour.

A report of 1939/40 stated that

“the present position is that the traffic passes 40% by steam lighters and 60% in horse drawn barges and lighters. No towing is done by means of tugs or steamers… The bulk of the transport on the Forth & Clyde Canal is in the hands of two firms. Messrs J Hay & Sons, have a fleet of 19 (24) steam lighters and 32 (8) horse-drawn barges, and Messrs G & G Transports Ltd have two steam lighters, 18 horse-drawn barges and 13 horse-drawn lighters… There is also a passage steamer which runs daily in the summer time, May to September, between Glasgow and Craigmarloch, owned by James Aitken Ltd, Kirkintilloch. This is a very old establishment. Certain steam lighters belonging to various individual owners plying around the East and West coasts use the Canal. Messrs Ross & Marshall Ltd, Greenock, for instance, have a fleet of such steam lighters.”

(National Archives BR/FCN/4/1)

.

For a dozen or so years there were no passenger steamers on the Forth and Clyde Canal. Then, in 1893, James Aitken, a son of the skipper of the Rockvilla Castle, placed a new steamer, the Fairy Queen, on the canal at Craigmarloch near Kilsyth. She was purely a pleasure steamer operating only in the summer months. She proved so popular that she was replaced by a larger vessel of the same name in 1897 and another legend was born (for which see Martin 1977; Bowman 1984). The Fairy Queen was followed by the May Queen and then the Gipsy Queen. The demise of this much-loved institution was sympathetically described in the Kirkintilloch Herald of 5 June 1940:

“As the crocus is the harbinger of Spring, so was the appearance of the ‘Gipsy’ on the canal a sure indication that another summer season was upon us. This year children, and adults too, in the towns and villages through which the ‘Gypsy’ passed on its daily voyages, waited in vain for the appearance of the ‘Queen’, but she remained stationary at Craigmarloch. On Monday of this week she moved off again – not under her own power, but drawn by two stalwart horses – on her last voyage. She was bound for Clydeside, where, it is understood, she is to be broken up.”

The canal era was over and so was the use of steam power. From 1770 to 1860 horses were the norm on the Forth and Clyde Canal. From then until the 1930s steam became more visually dominant before traffic was run down. Now the ubiquitous diesel engine is used. In their wake the boats of the canal have left a rich heritage of innovation and industry. Falkirk was to the fore in inventiveness and experimentation.

Bibliography

| Bowman, I.A. | 1981 | Symington and the Charlotte Dundas. |

| Bowman, I.A. | 1984 | Swifts and Queens: passenger transport on the Forth and Clyde Canal. |

| Bowman, I.A. | 1991 | in Forth and Clyde Canal Society The Forth and Clyde Canal Guidebook (2nd ed). |

| Hutton, G. | 2002 | Scotland’s Millennium Canals: The survival and revival of the Forth & Clyde and Union Canals. |

| Lindsay, J. | 1968 | The Canals of Scotland. |

| Martin, D. | 1977 | The Forth & Clyde Canal: a Kirkintilloch view. |

| Mitchell, S. & Ronald, A. | 2007 | ‘A historical and archaeological study of Tophill Dock, Camelon, Falkirk,’ Calatria 24, 79-106. |

| Paterson, L. | 2006 | From Sea to Sea: A History of the Scottish Lowland and Highland Canals. |

| Rankine, J. & W.H. | 1862 | Biography of William Symington, Civil Engineer: Inventor of Steam Locomotion by Sea and Land. |

| Ronald, A. | 2011 | ‘The boat building yard at Port Downie,’ Calatria 27, 77-88. |

| Shovlin, D. | 1996 | ‘Thomas Wilson of Tophill; builder of Scotland’s first iron ship,’ Calatria 10, 73-84. |

| Somner, G. | 2000 | ‘The Carron Company,’ British Shipping Fleets (ed) Fenton, R. & Clarkson, J., 162-188. |

| Wilson, R. | 1860 | Screw Propeller: Who Invented it? |

| Wilson’s Log | See Falkirk Council Archives Website | |

| British Newspaper Archive. | ||

| https://sites.google.com/view/williamsymington |