In 1835 a Prospectus was published along with a report by the famous engineer, John Macneill, for the construction of a canal from near Castlecary on the Forth and Clyde Canal to Stirling. At the time railways were in their infancy but were gathering a head of steam. The Prospectus therefore went out of its way to explain why the promoters had chosen a canal rather than a railway for this line of communication. It fully admitted that railways were faster, but pointed out that they were less efficient than canals for the carriage of heavy goods. For passengers, canals were far more comfortable, the ride being quieter and smoother, and the accommodation being less cramped. The passenger boats could stop anywhere along the length of the canal, whereas the trains required so much energy for the locomotive to start up that the railways only provided a limited number of stopping places. One of the most important factors laid before the public was that canals were cheaper to build. The cost of forming the Stirling Canal, it was boldly stated, would not exceed a fifth of the actual cost per mile of the Liverpool Railway. Of course it made no mention of the difficult terrain that that railway had had to traverse. Macneill estimated the cost at £93,681 and so the capital of the company formed for its construction was set at £100,000 in 2,000 shares of £50 each. The joint stock company was to be called the “Stirling Canal Company.”

At the time speed was not considered important. A railway, 11.5 miles long, from Stirling to Castlecary, would mean a travel time of about 40 minutes if there were no stops, as on the Liverpool Railway. For a canal on the same line the travelling time would be 1hr 10mins. On the other hand the fare cost of travelling for each passenger on the Liverpool Railway was upwards of 2d per mile; on the Paisley Canal it was only ½d per mile. That year the Paisley Canal carried 373,290 passengers. The journey from Stirling to Glasgow using the new Canal would be performed in three hours or three hours and a quarter; and the average fare for this journey would not amount to 2s.

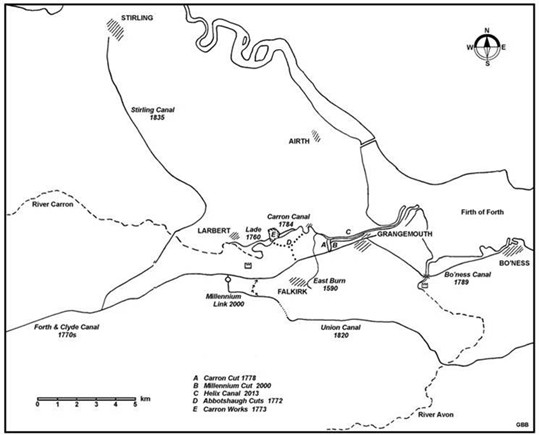

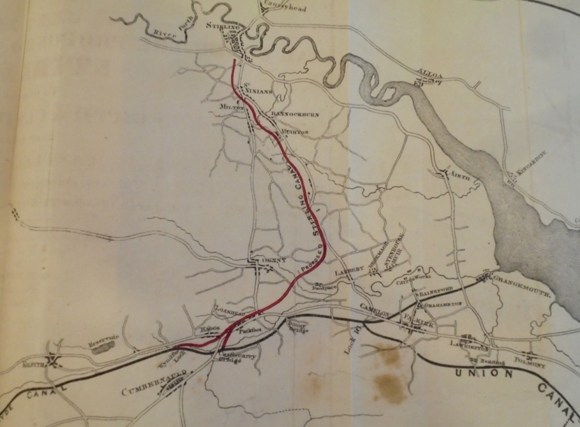

As the Stirling Canal was never constructed. It is best to give its proposed line as set down in the 1835 Prospectus:

“When the Stirling Canal was first proposed, three different lines were examined – an east, a middle, and a west line, all leaving Stirling nearly at the same point, but at different levels. Of these, the middle line has been adopted, as that keeping free from interference with gentlemen’s pleasure-grounds, and at the same time capable of being formed without locks, preserving the same level water route from Stirling to Glasgow. The east and west lines would have been longer, and subjected to lockage, and must have interfered with the pleasure-grounds of gentlemen living on the line.

The middle line, which is free of both these objections, commences in grounds belonging to the Corporation of Stirling, nearly opposite the new Grain-market, and proceeding thence, it skirts the town of St. Ninians on the west. The line then crosses the turnpike road to Glasgow near the point where it is joined by the parish road to Sauchie. Under these roads, the Canal is to be carried at a depth of 14 feet, affecting neither their lines or levels. The line then passes close by the manufacturing village of Bannockburn, and the valuable collieries belong to Mr. Ramsay of Barnton, leaving the pleasure-ground of Bannockburn (the property of Mr Ramsay) to the right. Passing these collieries, the line proceeds towards the estate of Plean, and passing on the east of Plean House, and on the west of Carbrook House, the property of Mr. Campbell, it passes through the estates of Major Dundas and Sir Gilbert Stirling, entering by a tunnel into the estate of Dunipace. Here it is carried over the river Carron and the Denny road, by a fine aqueduct. The line at this point passes about half a mile to the east of the manufacturing village of Denny. It then intersects a small portion of the estate of Herbertshire, the property of Mr. Forbes of Callendar, M.P., and bending to the west, runs parallel with the line of the Forth and Clyde Canal, but on the opposite side of the valley in which that Canal is situated, till it joins the extended summit level of that navigation near Castlecary. In this portion of the line, the Canal passes under the Stirling and Kilsyth turnpike roads, but without affecting the line or levels of either. By carrying the line about a mile farther west, the present summit level of the Forth and Clyde canal would be equally attained; but as it is the intention of that Canal Company to carry forward the summit level towards Castlecary, this additional mile of the Canal is saved.

The entire length of the new Canal above described, is about eleven miles and a half; and at a very considerable expense, in case the passenger trade should require such accommodation, it might be carried on a level into the new Corn-market, situated in the very centre of the Town of Stirling.”

Despite the statement in the Prospectus that the chosen line did not interfere with gentlemen’s pleasure grounds there were objections to the necessary Parliamentary Bill on that very point. John Campbell of Carbrook wrote to his Member of Parliament:

“I trouble you with this application which goes no further than to ask for justice. You are so far acquainted with Carbrook as to know that it has been lent out as a Residence and is chiefly valuable in that view and that a canal running through it within 100 yards of the house must destroy that value. If the canal keep along the old Turnpike road it would have cutting for about 800 yards and at the greatest depth about 50 feet through rock a great part of which they would have to blast. I suppose they could not do it under ten or fifteen thousand pounds and to save that expense they propose to come down near the level to do which they destroy my place. I understand they will not be permitted to do this. Let them buy the place and then they may save their money as they would not probably lose above £4000 by reselling after the Canal is made.” (Forbes Papers 1234/2).

John Muirhead’s villa at Headswood on the south bank of the River Carron near Denny was also too close to the proposed line for its owner’s liking, and he too wrote to William Forbes M.P to change the Bill.

“I think, I must confess, be very sorry if it did pass without at least some alterations on the proposed line of this Canal; because if this line were acted upon, the operations would almost destroy the amenity &c of my little Villa of Headswood – Cottage (which I now hold under you by a Lease from my late Brother) – It will appear by the place of the proposed line, how very near to the Cottage the Canal would pass: & if therefore, you think any means could he suggested for averting their most material injury (in which you are yourself ultimately interested)” (Forbes Papers 1234/12).

The expense of the proposed canal was to be kept to a minimum by making it a contour canal, thus saving on the construction of locks even though it increased the distance. Just as importantly, this meant that the loss of water would be negligible and so an agreement was reached with the Directors of the Forth and Clyde Canal Company that it would provide most of the water, with only a small amount of local topping up required. This, it was thought, would counter any objections that the landowners might otherwise raise about the water courses that the canal was to cross – the streams to be culverted. It was indeed a source of great concern and in March 1836 Thomas Graham of Airth Castle received a note assuring him that

“It will only require you to state that the line of the Canal crosses the Springs and rivulets which (supply) Airth Mill, & to see that Security is given in the Act that these Supplies shall not be interrupted nor the water diverted to any other purpose.” (Forbes Papers 1234/7; see also Airth Papers Ms10867 347 & 352).

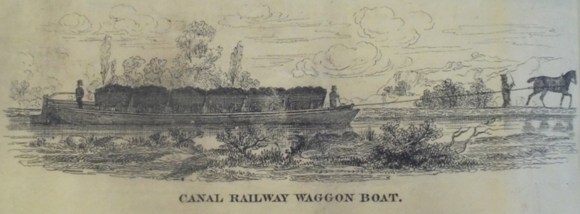

Contour canals had come about as a result of experience in the use of inland waterways and although they might require expensive aqueducts, they also saved on the time taken to go through the locks. That same acquired knowledge showed that a towpath on either side of the water channel was the most efficient form as it allowed boats to pass each other without their towropes becoming entangled – particularly useful in the dark. The Stirling Canal was therefore to have two towpaths. It was also to have a relatively narrow waterway, between 25ft and 30ft broad, with a depth of only 4ft. Practical experimentation had shown that this smaller size would reduce the drag on the vessels and hence the traction power required. On Scottish canals it was the custom for one boat to be pulled along by a single horse and steersman, by which means cargoes of 45-70 tons were conveyed. On some of the English canals several smaller boats were then in use in a train, each one attached to the one in front, and by that means they were enabled to draw 120-140 tons, and still they only required one steersman on the foremost boat.

The boats to be used on the Stirling Canal were to be of the latest design. Passenger boats would have followed the innovative designs that had proved so successful on the Paisley Canal. Cargo carriers would be of the roll-on roll-off type, avoiding the delays for loading and unloading needed for bulk cargoes.

The estimated revenue of the Canal was:

| 60,000 tons of Monkland coal carried on an average 9 miles along the Canal, at a toll of a penny per mile, for the use of manufactories, &c. of Denny, Bannockburn, St. Ninians, Stirling, and the inhabitants on or near the line. | £2250 | |

| 30,000 tons of smithy coal from Bannockburn and Auchenbowie collieries, carried on an average 9 miles along the Canal to Glasgow, Paisley, Port Glasgow, &c. at a penny per ton | £1125 | |

| 40,000 tons of stone, lime, and manure, carried on an average 8 miles along the Canal at a tonnage of three farthings per mile | £1000 | |

| 30,000 tons of malt, grain, timber, sugar, iron, dye-stuffs, manufactured goods, and valuable raw produce, &c. passing in each direction between Stirling, Glasgow, Port Glasgow, and Greenock, at an average tonnage of one shilling | £1500 | |

| 20,000 tons of potatoes, turnips, and less valuable farm produce, sent from the line of Canal to Glasgow, Paisley, &c. at an average toll of sixpence, or one half-penny per mile | £500 | |

| 120,000 passengers carried along the line of Canal to or from Glasgow, Edinburgh, Paisley, Greenock, Port Glasgow, &c. at an average fare of three farthings per mile, or a total fare of ninepence | £4500 | |

| 40,000 intermediates, at an average fare of sixpence | £1000 | |

| £5500 | ||

| Deduct expense of running boats | £1750 | |

| £3750 | ||

| Proportion of fares of night van and passenger boats between Stirling, Edinburgh and Glasgow | £1000 | |

| £11,125 |

If £1,250 was deducted from this amount as the expense of maintaining and keeping up the Canal, there remained £9,875 to be divided among the subscribers, which would afford a dividend of 10% on the sum expended in the formation of the Canal.

From the estimated income it can be seen that agriculture and manufacturing industry were of great importance, as was the passenger service. Consumers were also considered:

“By the establishment of Night Fly or Van Boats, similar to those now plying on the Canal between Edinburgh and Glasgow, a still cheaper night conveyance will be offered to the poorer classes; and the merchants and shopkeepers of Stirling will be enabled to send or receive parcels and packages to or from Glasgow and Edinburgh, conveyed by these night boats, during the interval of all businesses, at a third of the cost they could be sent by any other conveyance whatever.”

This, the forerunner of Internet shopping!

A Bill was presented to Parliament in January 1836 and had its first reading that February. Shares went on sale and the Forth and Clyde Canal Company agreed to subscribe £50,000 (Lindsay 1968, 190). The local M.P., William Forbes of Callendar, was canvassed by both those for and those against the Bill. They fell into two camps – the farmers and local merchants were generally in favour; whereas the landowners and merchants further afield were vociferously against. Forbes seems to have been ambivalent about the Canal and privately supported either side. In public he was in favour. He had recently acquired the Herbertshire Estate in Denny and the Canal would take some of his land, for which he would be compensated and the value of his remaining land would be enhanced. Charles Stirling, one of his political allies, counselled him to be careful:

“Whether the Stirling Canal & the proposed Great Edin. Railway, will do the subscribers any good, I very much doubt, but the Country in general & the £10’s in particular, have a great fancy that they are to be all much the better of them. I am aware that the Canal will have the opposition of the Road Trustees, but when in Stirlingshire the other day, the only News that I could hear of, that the men against it, were Polmaise, Sir Gib. Stirling & Tam Dundas Carron Hall… need go very far out of your way to oblige all or any of the three, and I am well aware that your Enemies think that they have got you into a scrape, I think that you are to lose a great deal by opposing these undertakings – K. Finlay, Kilmond & all the Great Canal Proprietors, are of course keen for the Stirling Branch, and if it goes on I should think it would rather be a benefit to your new purchase.

Ramsay was with me for ten days lately. He is not in favour of it, but I do not think he cares much about it. K. Finlay spoke to me a few days ago about it, & told me that a few of the Road Trustees were concerned, they had no objections to refer the damage to be done to the Trusts to any impartial man – At all events I do not think you should oppose this Canal Bill, if you possibly can avoid it. Captain Speirs asked me with a grin, “What is Forbes going to do about the S. Canal & Railway”- I answered , “support them both to be sure for the good of the Country”, upon which his mouth opened, but nothing came out” (Forbes Papers 1234/4).

The five main promoters of the Stirling Canal were shareholders in the Forth and Clyde Canal Company and received considerable support from it. James Chrystal was the agent for the Canal Co in London. All seemed set fair for rapid progress. The bureaucracy was to bring that to a shuddering halt. As a result of the objections from those with water rights along the proposed route it was noted that standing orders had not been followed in notifying them and the Bill was referred back to the Standing Orders Committee. Having got wind of this problem, the Forth and Clyde Canal Company made its own application for making a canal from Loanhead to Stirling – essentially the same Canal with the addition of three short branch lines at a total cost of £110,000. In this new version it was to supply all of the water necessary. It was felt that if one Bill failed, then the other would succeed. However, it did not take a genius to realise that the proprietors of the water supplying the Forth and Clyde Canal had not been notified either and had not authorised its use for the new construction, and so it too was referred to the Standing Order Committee.

Both Bills languished there unto March 1837 when the Committee reported that, in the case of the Loanhead-Stirling Canal, the parties were permitted to proceed with their Bill on abandoning that part of the canal which lay between the town of Stirling and the Whins of Milton, unless with the consent of William Murray Esq. The first Bill was also cleared to proceed.

In the meantime the merchants in Leith had become greatly perturbed over the proceedings and believed that the new Canal would reduce their trade. They also considered that the Canal was a ploy to use up the income from the Forth and Clyde Canal so that its owners would not be required to lower the freight rates upon that canal which would otherwise become due as a consequence of the surplus profit that it was now earning. The Incorporation of Traffickers or Merchant Company of Leith submitted a petition against the Stirling Canal. Petitions against were also received from the merchants of Arbroath and the agriculturists in the neighbourhood, of Montrose and Brechin.

In April 1837 William Forbes moved the second reading of the Loanhead and Stirling Canal Bill. Admiral Adam rose to oppose the second reading of the Bill because it had been opposed by the Chamber of Commerce of Edinburgh, and by nearly all the proprietors on the line, whose property would be sacrificed by it. The House was incensed by the fact that the introduction of two Bills meant that parties opposing the Bill would be subject to double the expense, or confused as to which to halt. Sir Robert Peel said that, if true that the two Bills had been brought in to affect the same object, he thought that principle was so objectionable, that on that single ground he should give his vote against the Bill, and he trusted the House would mark its sense of such a proceeding by rejecting it altogether. The Bills were consequently lost.

Whilst all of this was happening, John Macneill surveyed and then constructed the Slamannan Railway and it was partly due to his influence that locomotives, rather than horses, were used on it from the beginning.

Bibliography

| A copy of the Prospectus may be found in Falkirk Archives and in the collections of the National Library of Scotland. | ||

| The Forbes Papers are in the Falkirk Archives, and the Airth Papers in the National Library of Scotland. | ||

| Lindsay, J | 1968 | The Canals of Scotland. |