SMR 2345

For over half a century from around 1700 the great Falkirk Trysts were held at Whitesiderig and Reddingrig Muirs near Shieldhill. These were huge gatherings where each year tens of thousands of Highland cattle and sheep were sold to English dealers and produced over a quarter of the nation’s income. The animals came from all over Scotland, including its outer fringes, and were fed into the market using a nebulous network of drove roads. Many of these routes united as they got closer to the market site and the roads were packed with animals. Just before reaching the Tryst ground there was a brief opportunity to rest the beasts and recondition them on pasture rented out for the purpose in the parishes of Deny, Larbert, Airth and Falkirk. The author of the New Statistical Account for the parish of Larbert noted that “practically every piece of ground in the district was used for grazing.” Conversely, the animals were led away from these muirs on green roads that bifurcated time and time again so that the animals could find grazing with reduced competition. The first days of this journey were spent in the parishes of Polmont, Muiravonside and Slamannan. Here the need was to rapidly move the animals away from the market site to make room for the next batch and over the years a series of temporary halts or stances were established.

The Tryst ground was on a common muir in the parish of Falkirk (later incorporated into the new parish of Polmont) and the Duke of Hamilton benefitted from the moderate charges that his factor was able to levy for its use. For the drovers it provided a large open space for the cattle to graze and for them to transact their business with the buyers. The site also benefitted from its proximity to the huge commonty of Muiravonside to the south-east (Reid 1994). This vast expanse of moorland gave them space to spread out from the bottleneck of the market. Its division and subsequent enclosure started at around the time that the trysts started up but was gradual and slow. For historians of the trysts this has the added benefit that residual portions of the muir which could be used for the grazing of the cattle were given new place names associated with this usage.

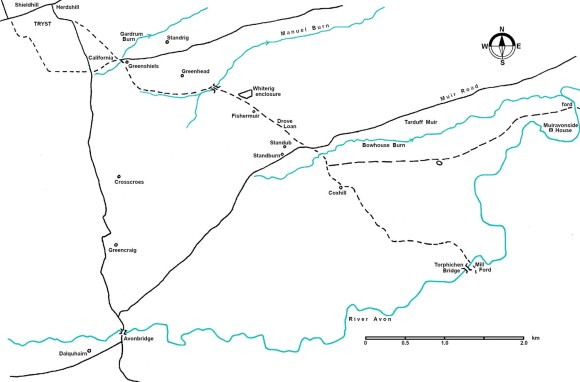

The main road from the Tryst ground led south-eastwards passing through the area later occupied by California, through Craigend to Standburn. From there they went on to Coxhill where there was a choice of ways – south to the Mill Ford on the River Avon near to where Torphichen Bridge was later built, or east along the ridge through Muiravonside to a ford near Woodcockdale. These drove roads are depicted on Roy’s map of 1755, but apart from sections south of Coxhill they have all been abandoned and now exist either as green lanes or else have been eradicated by the agricultural improvers of the nineteenth century.

The first part of the route, from the Tryst ground, is now unrecognisable due to the subsequent activities of coal mining and the later village of California. As the modern road emerges from the east end of California it descends a short brae to the Gardrum Burn and then turns east towards Maddiston. Such streams provided watering places for the animals and so it is not surprising to find a little downstream a farm named “Standrig” (1780- Reid 2009, 314). The rig refers to the west/east ridge and stand is a variant of stance for the cattle. Adjacent to Standrig was “Back o’ the Stand” (1789). On the south side of the stream at this point is a cottage called “Greenshiels”(1898) a name which it has had since at least 1898 (Falkirk Herald 14 December 1898, 6; it is shown but not named in the 1860 Ordnance Survey map). In this name the element “Green” refers to the pasture, and “shiels was a place for grazing cattle, initially in the winter but later all year round. There is another “Greenshields” (1855) near Compston, also in Muiravonside parish. As the modern road at the Gardrum Burn turns to the east a track used to head SSE with a spur off to the east to Middlerig Farm. Passing that farm the track descended the hill to the Manuel Burn and then turned east, its course obliterated during the construction of the Blackbraes Branch Railway (SMR 1965). The stream provided another opportunity to water the cattle. The railway followed the old drove road for the next half a mile and on its north side we find “Greenhead” (1817) which evidently lay above a place for grazing.

The drove road then cut off to the south-east, crossing the Manuel Burn by a stone bridge. Such bridges were not necessary for the cattle, especially here where the bed of the stream is formed by bedrock. This road was also a main route for other traffic. Here the drove road formed the western boundary of the estate of Parkhall and was referred to as the “Drove Loan” (Caledonian Mercury 5 June 1820, 1). This part of Parkhall was made up of the lands of Craigend and Whiterigg.

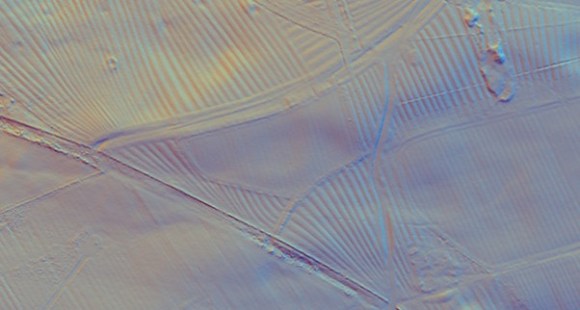

The extensive presence of earthworks of rig and furrow to the east of the drove road shows that that area had been developed for arable cultivation in the 17th century (SMR 2346). To the west the land was once part of Muiravonside Muir. It is not surprising therefore that the broad drove road to the south of the Manuel Burn was confined by a stone dyke on its east side intended to keep the animals away from these fields and their crops, whereas it had a more slender earth dyke on its west side.

Just at the top of the first crest a wide green track makes a junction with the Drove Loan on its east side. The configuration of the rig and furrow here suggests that this was contemporary with them. Of a slightly later date is a small enclosure on the south side of this green track. It is surrounded by an earth bank upon which trees have been planted. The interior once held broad rig and furrow but this has been flattened. The enclosure is not shown on Grassom’s map of 1817, which shows the entire area right down to the Manuel Burn as woodland. This agrees with the 1822 advert stating that “the Plantations on this Estate [Craigend] are of very great extent” (Caledonian Mercury). The wood was considered to be fit for stobs and rails, suggesting that the trees were not old. It is probable that the western field was deforested and the enclosure formed as part of the creation of the estate after the sale of 1820 when a new mansion was built. Although the enclosure is on a south-facing slope, the woodland to its south would have hidden it from the new House and so the purpose of the enclosure is uncertain. It is possible that it provided a secure area for the cattle using the Drove Loan. A little further along the road was a small steading known as “Fishermuir.” As the name suggests this was located adjacent to a muir, which in this case belonged to the Fisher family. It seems to have been a remnant of the massive commonty of Muiravonside, the subdivision of which had begun at the very end of the 17th century. As such it would have been available to the drovers.

Dipping down into the next shallow valley the drove road encounters the Bowhouse Burn, another local name for which was the “Standburn” (1817). “Standub” (1798), near Standburn, means “the stance at the small pool” (Reid 2009, 314). The pool probably lay in what is now Drumbowie Park to the north of the modern village of Standburn where Roy shows marshy ground. From here the drove road crosses the Muir road which runs from Avonbridge to Linlithgow Bridge. Ascending the ridge on the south side of the valley it reaches “Coxhill” (1562) – a hill frequented by grouse or blackcock. Nearby was “Pundfauld” (1669) – a place for holding stray or impounded cattle (Reid 2009, 213). It, however, was in existence as early as 1669, before the Falkirk Trysts commenced. There was, of course, a considerable trade in cattle before 1700 but it is probable that the cattle in this particular case were from one of the several commonties in the area.

From Coxhill to the A801 the old drove road follows the crest of the prominent ridge and appears as a narrow sunken green lane. Drystone dykes have been inserted to convert it into a farm track. On the east side of the A801 the course if followed by the West Drive of Muiravonside House and has been slightly re-engineered. As it passes through the woodland belt a series of parallel earth banks show the precautions taken to confine the cattle to the track. At the Avon the river broadens out and has a firm gravel bed at the ford which was used well into the 20th century by shepherds.

Another major drove road went due south from the Tryst ground to make for the crossing on the River Avon at Avonbridge which, as the name suggests, was by a single-arch stone bridge (SMR 871) built in 1640 by the first Earl of Callendar. This was the bridge referred to in 1723 by Johnson of Kirkland :

“the bridge at Dalquhairn, along this bridge goes the Highland Cattle from the markets at Fallkirk in their way to the borders of England” (MacFarlane 1906).

At the time this was known as the West Bridge of Aven to distinguish it from the East Bridge which became known as Linlithgow Bridge. A little to the south-west of the bridge were the lands of Dalquhairn (SMR 865) where the Shaw family were able to profit by letting the riverside meadows to the drovers. A little to the north-east of the bridge was “Greencraig” (1701) meaning grazing at the quarry (Reid 2009, 284). The only other place name that might be associated with the droves was “Crosscroes” (1710) – an enclosure by the crossroads (Reid 2009, 216).

Some droves headed east taking either the Maddiston Road from California or the Muir Road from Standburn. These led to Linlithgow Bridge where the pontage fees charged by the royal burgh of Linlithgow deterred many. The burgh attempted to impose these taxes upon the cattle trucks using the Avon Viaduct on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway after if opened in 1842 but eventually lost its case in court. From then on the transfer of cattle and sheep to the south of England inevitably moved on to the rails.

Bibliography

| MacFarlane, W. | 1906 | Geographical Collections Volume 1; Johnston of Kirkland. |

| Reid, J. | 1994 | ‘The Feudal Land Divisions of Muiravonside Parish: the principal subdivisions,’ Calatria 7, 21-85. |

| Reid, J. | 2009 | The Place Names of Falkirk and East Stirlingshire. |

| New Statistical Account Larbert | “For many years there was held in the parish the Falkirk Tryst, a large cattle and horse market. This was an important event as it was the chief contact between the Highland sellers of livestock and the buyers in the Lowlands. The old members of the community can recall the crowds of people and the stirring scenes when the Trysts were held, and practically every piece of ground in the district was used for grazing.” |

NEWSPAPERS

Edinburgh Evening Courant 20 March 1786 , 3c:

To be let for 19 years Woodside Farm situated on each side of the post road leading from Falkirk to Stirling, 4 miles from the former. Completely enclosed, sub-divided, in sheltered location, and well watered. “It is well situated for a grazier, and lies convenient for drovers and others that frequent the Falkirk Trysts; and the grass and foggage always lets at a good rent.” Upwards of 100 Scots acres.

Caledonian Mercury 8 June 1822, 1:

Stobs and Rails, of excellent quality. A great proportion of larch wood, are for sale on the Estate of CRAIGEND, in the parish of Muiravonside, and county of Stirling.

- As the Plantations on this Estate are of very great extent, the Proprietor is induced to dispose of the Thinnings at a very moderate rate; and from their being almost adjoining to the Union Canal, about five miles west of the town of Linlithgow, the stobs and rails can be conveyed by water carriage to any part along the line, or to Edinburgh, at a trifling expence. Particulars may be learned by application at Craigend House, by Linlithgow; and orders sent there, or to William Taylor, wood forester at Manuelrig, will be carefully attending to.