SMR 2346 / NS 93 76

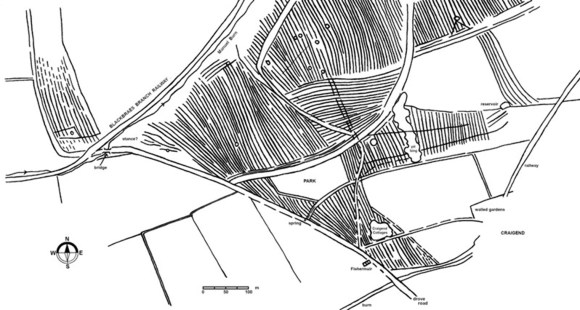

Roy’s map of 1755 schematically depicts areas of arable cultivation as a series of closely-spaced parallel lines representing rig and furrow. It provides a snapshot of the extent of the intensively worked land which had reached its zenith around this time. Down on the lower ground around Falkirk, Airth and Bo’ness, this patchwork is made up of relatively small tightly interwoven fields, but on the higher ground of the braes they are larger and less confined.

In pre-improvement lowland Scotland arable land was usually cultivated in blocks of broad rigs which were formed by repeatedly ploughing in the same direction, turning the soil towards the centre of each ridge. This action raised the height of the ridge and developed a furrow between each rig which acted as an open drain. For this latter reason the rigs were aligned with the slope of the ground. Their breadths varied, but broad rigs were typically anything between 4.5m and 14m in breadth. They often developed a reverse S-shape as a consequence of the plough being swung round towards the end of the rig. The individual blocks of rig were not normally enclosed by fences, hedges or dykes, but were separated from grazing land by head-dykes.

From the late 18th century onwards this system of cultivation was slowly replaced by enclosed fields worked by the more efficient swing ploughs, followed in the mid to late 19th century by the introduction of subterranean field drains. Slowly the physical traces of the rig and furrow disappeared from sight. Ceramic drains were, however, expensive and in some of the higher land the open furrows were allowed to remain. Part of the process of agricultural improvement also included the formation of shelter belts and the planting of larger areas of woodland, and in these areas the old furrows continued to provide the drainage.

The RCAHMS noted the large extent of the rig and furrow in its survey of the area to be occupied by the Central Scotland forest (RCAHMS 1998, 50-53). Such afforestation has had a devastating impact upon the physical remains of the rig and furrow. Pockets of it survive (ibid, aerial photographs in figs 2, 50 & 52), and the largest of these in the Muiravonside parish is at Craigend/Whiterigg to the south of the Manuel Burn which was part of the old estate of Parkhall.

There is a marked contract between the extensive presence of earthworks of rig and furrow to the east of the Drove Loan and their absence to the west where the land was once part of Muiravonside Muir. Here the road was confined by a stone dyke on its east side intended to keep the animals away from these fields and their crops.

Just at the top of the first crest a wide green track makes a junction with the Drove Loan on its east side. The configuration of the rig and furrow here suggests that this was contemporary with them. Of a slightly later date is a small enclosure on the south side of this green track. It is surrounded by an earth bank upon which trees have been planted. The interior once held broad rig and furrow but this has been flattened. The enclosure is not shown on Grassom’s map of 1817, which shows the entire area right down to the Manuel Burn as woodland.

Bibliography

This agrees with the 1822 advert stating that “the Plantations on this Estate [Craigend] are of very great extent” (Caledonian Mercury). The wood was considered to be fit for stobs and rails, suggesting that the trees were not old. It is probable that the western field was deforested and the enclosure formed as part of the creation of the estate after the sale of 1820 when a new mansion was built. Although the enclosure is on a south-facing slope, the woodland to its south would have hidden it from the new House and so the purpose of the enclosure is uncertain. It is possible that it provided a secure area for the cattle using the Drove Loan.

| RCAHMS | 1998 | Forts, Farms and Furnaces: archaeology in the Central Scotland Forest. |

| Whyte, I. | 1979 | Agriculture and Society in Seventeenth Century Scotland. |