THE SOCIAL IMPACT OF A MILITARY PRESENCE

IN FOUR PARISHES OF THE FALKIRK DISTRICT 1660-1790

The Army at this Period

The nature of an army as we know it was a development of the War of the Three Kingdoms. Prior to the mid-seventeenth century monarchs raised armies by calling on their nobles to muster their own territorial forces composed largely of their tenants (levy) and their own trained followers (retinue). Mercenary troops were also available for hire. The New Model Army, raised by Fairfax and led by Cromwell, provided a template for future ‘standing armies’, forces of full-time professional soldiers available at all times and not just at moments of crisis. Armies were composed of organised units of infantry, cavalry and artillery with uniform clothing and equipment. Officers were largely drawn from the gentry and aristocracy.

Why were Troops Stationed in this Area?

Troops were stationed in Scotland to deal with civil unrest or threats, and occurrences, of internal rebellion or foreign invasion. From 1660-88 the threat came from the Covenanters and we have evidence of forces stationed at Airth and at Falkirk in the period. Jacobite risings occurred in 1690, 1715 and 1745-6 and the threat of further outbreaks was present until the second half of the 18th century. The country was at war with France for most of the 18th century and threat of invasion was taken seriously.

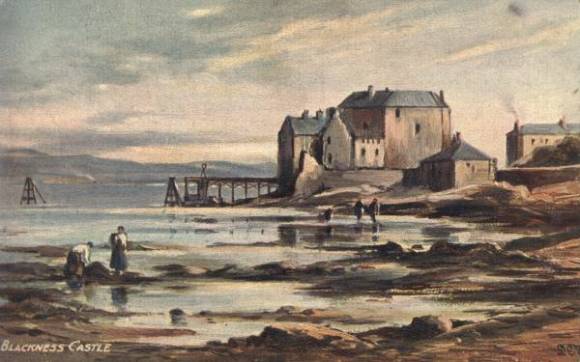

Soldiers were stationed locally at Blackness Castle and at Stirling Castle, but smaller units were also billeted in some towns themselves. We have evidence from the kirk session records of such billeting in the parishes of Airth, Carriden, Bo’ness and Falkirk. Billeting was often used as a punishment as much as a deterrent, especially in the late 17th century. After the Pentland Rising and battle of Rullion Green in 1666 the threat, and actuality, of armed insurrection by the Covenanters led to troops being quartered in areas where they were in strength, especially the south-west of Scotland where in 1678 the Highland Host was quartered on a dissident population. 1679 saw the two battles of Drumclog and Bothwell Brig and in January 1679 Blackness Castle was garrisoned.

The Falkirk area was known to be supportive of the Covenant; in the late 1670s conventicles were held at Bo’ness, Denny, Torwood, and the Black Loch near Slamannan. The second Earl of Callendar was himself sympathetic to the Covenanters and government troops were billeted at Callendar House in 1675 and 1678 as a form of punishment. Earlier, in 1667, ‘Sir Robert Dalzell his company’ were quartered on Airth. Dalzell of Glenae [1639-86, created baronet in 1666] was also active in suppression of Covenanters in 1685.

From the first Jacobite Rising of 1690 through to and after that of 1745-6 there was an almost constant presence of troops in the parishes mentioned. Battles were fought at Sheriffmuir in 1715 and at Falkirk itself in 1746. The units involved in forming a kind of garrison at Falkirk were as follows [NB A troop of dragoons consisted of between 25 and 30 men at this period]:

- 1693-99 Sir Thomas Livingstone’s Regiment of Dragoons

[Livingstone [1651-1711], later first Viscount Teviot, was born in the Dutch Republic and spent his career in the service of William of Orange. He was deputy to Hugh Mackay during the Jacobite Rising of 1689-90 and was C-in-C Scotland from 1690-96. He had replaced Lord Charles Murray, 1st Earl of Dunmore, as colonel of a dragoon regiment.]

- Colonel Leslie’s Regiment of Foot

- Lord Morrow’s Regiment of Foot

[This could be Lord Murray and possibly refers to Lord Charles Murray, 1st Earl of Dunmore]

- 1703 Captain Hamilton of Raploch’s troop

[Archibald Hamilton of Raploch]

- 1709 Major Douglas’s troop

- 1710 Captain Farrer/Farrow’s troop of the Earl of Stair’s Regiment of Dragoons

[John Dalrymple (1673-1747), 2nd Earl of Stair. His regiment, Royal Regiment of North British Dragoons, is better known as the Scots Greys]

- 1716 Evans’s Regiment of Dragoons

- 1717 Captain Livingstone’s troop of Lord Ker’s Regiment

- 1719 Captain Millan’s troop

- Captain Brown’s troop

- Captain Farrer/Farrow’s troop

At Carriden:

- 1693 Captain Preston’s company

- 1694 Captain Balfour’s troop

At Bo’ness:

- 1713 Lord Hinchingburgh’s company [dragoons]

[Edward Montagu, Viscount Hinchingbrooke 1692-1722, in 1709 c/o of a troop in Sir Richard Temple’s Regiment of Horse]

- 1714 Major Butler’s dragoons

- 1716 Major Charles Huyas troop of Stair’s Regiment

- 1718 Stair’s Regiment and troop

- 1720 Harrison’s Regiment of Foot

- 1726 Deloraine’s Regiment

[Henry Scott, 1st Earl of Deloraine 1676-1730, 2nd surviving son of the Duke of Monmouth, illegitimate son of Charles II]

- 1730 Churchill’s Dragoons

[Charles Churchill 1679-1743, nephew of the Duke of Marlborough]

- 1744 Colonel Gardiner’s Regiment [dragoons]

- 1745 Colonel Gardiner’s Regiment

- 1747 Barrel’s Regiment

- Lord Sackville’s Regiment

- 1749 General Guise’s Regiment

- 1757 Colonel York’s Regiment

- 1758 General Cope’s Regiment

- 1760 Lord Charles Manners’ Regiment of Foot

- 1761 Lord Charles Manners’ Regiment of Foot 1775 The Queen’s Regiment [dragoons]

Where were Troops Billeted?

Only two references to actual places occur in the kirk session records. In 1711 we hear of ‘a dragoon quartered at Craigend’s in this town’ [Falkirk] and in 1720 we hear of a woman who ‘entered the Room where his [Thomas Aikenhead’s] Dragoons lay’ [also Falkirk].

The Social Impact

The evidence for the social impact of the presence of numbers of soldiers quartered on the civilian populations of what were at the time small market towns and fishing or trading ports is found in the kirk session records of the parishes involved. The kirk session acted as a church court which, among other things, policed the morality of the parishioners. The evidence for the social impact of military billeting on the said parishioners comes mainly from cases of women made pregnant by soldiers. In presenting this evidence it is important to avoid a trivialising prurience and to see the women involved as very largely victims rather than, as the kirk sessions almost always did, as guilty of sin and moral turpitude. How many of the pregnancies involved, one wonders, were the result of rape? For example, in the disturbed years 1745 and 1746 there is one woman who had a child by “a Highlandman of the Rebell Army who was guilty with her in Sept when they first past this place” and two women who had children by Hessian soldiers of the Hanoverian army. None of these men is given a name and the transient nature of their stay in Falkirk suggests no ‘relationship’ had been formed. The possibility, given that and the nature of the times and the reputation of soldiers in war, is that coercion may have been used here.

The women cited in the kirk session records may have been noticed as pregnant by the elders who supervised their ‘quarter’ of the parish, or they may have been reported by zealous neighbours. However, a major factor in encouraging them to report themselves to the session was the Act Anent Murthering Children passed by the Scottish Estates in 1690. Under this legislation a mother who concealed her pregnancy or gave birth with no-one else present was deemed guilty of murder if the child should happen to die. This was the case with Effie Deans in Scott’s ‘The Heart of Mid-Lothian,’ for example. The prospect of possible hanging if a child should die, especially at a time of high infant mortality, must have been a compelling encouragement to confess a pregnancy.

In terms of numbers, in the period 1660-1780 and across the parishes where troops were stationed [Falkirk, Airth, Bo’ness, Carriden], there were forty-five pregnancies as well as twelve irregular marriages. The way in which the kirk sessions dealt with the ‘offenders’ in both cases is instructive of thinking and attitudes to women and to sexual morality at the period. Irregular or clandestine marriages differed from the regular marriages which involved the reading of banns on three successive Sundays and being married by the minister in his parish church. Three forms of irregular marriage were legally valid in Scotland.

- ‘Per verba de praesenti’ involved ‘some present interchange of consent to be thenceforth man and wife, privately or informally given.’

- ‘Per verba de future subsequente copula’ involved a promise of future marriage without any present interchange of consent to be husband and wife, followed at a subsequent time by intercourse.’

- Marriage by cohabitation with habit and repute.

Relatively rare in the seventeenth century, irregular marriages were increasingly popular in the eighteenth century. Religious non-conformity was one reason along with ‘the activities of unauthorised religious celebrants whose numbers proliferated after Presbyterianism had become the established religion in 1688.’ Many of the celebrants of these marriages may have been Episcopalian clergy ejected from their livings at the time of the establishment of Presbyterianism. It is certainly the case that the kirk session records we have been examining provide examples of marriage certificates provided by such unauthorised clergy, often conducted in Edinburgh. For example, in Falkirk in 1703 ‘Mary Sutherland produced her Testificat of her being married to John Duff a dragoon in Captain Hamilton of Raploch’s Troop, by one Mr John Maithers.’ It reads

‘Dated at Edinburgh September 23rd 1703 before these witnesses Andrew Vanwick weaver in Falkirk and John Maithers younger. Sic subscribitur John Maithers.’

Among the reasons for an irregular or clandestine marriage were the need for speed or secrecy. T. C. Smout also suggests the presence of an urban sub-culture that was ‘irreligious and casual in its attitude to marriage.’ Kirk Sessions did everything in their power to discourage irregular marriages and to censure those who married irregularly. Fines levied for such marriages were to be given to the poor.

When it came to the process of trial and punishment by the kirk sessions there were marked discrepancies between the treatment of the women and that of the soldiers.

Frequently there was difficulty in getting soldiers even to ‘compear’ [appear] before the session in the first place. This could be because of the itinerant nature of the troops, moved at command from one town to another. In Bo’ness in 1714, for example, a trooper could not appear, ‘the Troop of Dragoons being gone out of the Town.’ On several occasions the commanding officers of the troops concerned dug their heels in and stonewalled the process of appearance before the session. One officer refused to appear because he regarded himself, as a member of the Church of England, to fall outwith the jurisdiction of the Kirk. In Falkirk in 1693 there was a long-drawn-out struggle to get soldiers to appear. The session sent letters and even one of their more socially elevated elders to try to persuade a commanding officer to enforce attendance:

“Sir Alexr. Livingstone of Glentirran to go to Captain Morrow and in the Sessions name intreat that the s[ai]d Capt. Morrow would be pleased to cause Daniel Wright, Huw Finlay, James Bairgh & George Dumbar (soldiers under his command in Sir T. Livingstone’s troop of dragoons) to compear before the Session & declare if the children brought forth by Heline Livingstone, Margaret Greig, Elizabeth Cowie and Heline Miller are belonging to them and give in report the next Session day.”

In spite of this visit on the 22nd of October from the son of the second Earl of Callendar no reply had been received by the 30th October. It was only on the 3rd of December that

“Capt. Morrow…. Answered that it not having been a practise among Sir Thomas Livingstone’s regiment of Dragoons before judication he had no will to cause any of his own troops Compear before Session until he acquainted the s[ai]d Sir Thomas thereof.”

On the 24th December it is recorded that

“Capt. Morrow has not acquainted Sir Thomas Livingstone of the Sessions desire to cause several of his own troop compear before the Session & acknowledge their fornication committed here in this parish. Theyappoint Sir Alexr. Livingstone to inform him of the samen & in name of ye Session intreat yt [that] he would be pledged to raise ym [them] Compear.”

It was not until the 4th of February 1694 that we learn that

“Sir Alexr. Livingstone had spoken to Sir Thomas Livingstone who wd [would] appoint his Captain to command the s[ai]d soldiers to compear before the Session.”

Failure to compear by a soldier could have serious consequences for the woman involved. In April 1693 Margaret Greig was punished not by the Session but by the civil magistrate because there had been no line from the soldier who had fathered her child.

Even when a soldier did compear and acknowledge the child or the sin of fornication he would always receive more lenient treatment than the woman involved. In 1714 in Bo’ness

“the Minister reports that he spoke with the Cornet of the Troop anent the scandal of uncleanness whereof he is accused by Isobell Gilmore and that he acknowledged he was guilty with her and that he is willing to give obedience as his Character will admit.”

The outcome was that Cornet William Eugen was given merely a sessional rebuke but Isobell Gilmore appeared three separate times in the place of public penance in the kirk. The same story is repeated in Falkirk, no mention of punishment of any kind for the soldiers involved but the women ‘entered to ye pillar’ and appearing ‘three times on ye publick place of penance.’ There were worse punishments than the creepie, or cutty stool, of course. The full force of the Session’s wrath was directed on two women in Bo’ness parish in December 1714:

“The session considering that Margaret Baird who uses to brew to such as have hire her through the town hath again fallen into the sin of fornication with a Dragoon as she alledgeth and that formerly she fell into adultery and before that into fornication also that Janet Williamson daughter of the deceast Gavin Williamson cooper is also with child to James Young sailor as she alledgeth but he denys the same and that some years ago she was guilty with several Dragoons and that then she being much spent with loathsome disease the effect of her lewdness she went from this place and being cured hath returned and fallen into fornication as said. The session having called these two women before them and dealt with them for their Conviction in order to ring them to Repentance and offering little or no appearance of Sorrow and fearing they may continue in their scandalous and whoreish carriage & way to Dishonour of God and prove a Snare to others in the place do refer them to the Magistrate that he may punish them conform to the demerit of their crimes and their ensnaring others in the place may be prevented.”

There is no evidence that any of the dragoons involved with the two women faced any form of punishment.

It was not until the 1780s that more serious attempts were made to get soldiers to face punishment and to take more seriously the statements of the women involved. A case in point is that of Isabel Walker of Falkirk. In March 1783 she and James Adam compeared before the session ‘desiring to have an irregular marriage confessed which the Session refused to do, alleging that at least according to common report a marriage subsisted between Sergt. Stevenson and said Isabel Walker.’ In the course of testimony from six witnesses, three men and three women, it appeared that during a stay of a year or so in Falkirk, Isabel Walker had had a child by Sergeant Stevenson which had later died while the sergeant was serving in Ireland. The evidence reveals the attitude to the affair of the soldier: when asked if he would make an honest woman of Isobel, Stevenson declared, ‘My pay.. has enough to do with myself altho’ I have no wife besides we soldiers make every town serve itself.’ Another witness wrote to the session declaring that he ‘was fully convinced in my own mind from the artful evasive manner in which [Stevenson] expressed himself that he only meant to amuse but had no serious intention of marrying her.’ As a result of this evidence the session came to a conclusion on the side of Isobel Walker and James Adam:

“The Revd Moderator reported that the Presbytery [whither the case had gone] put no stress on the pretended marriage between Isabel Walker and Sergt. Stevenson and therefore gave it as their opinion that she is at full liberty to marry. Which the Clerk is ordered to intimate to James Adam as the sentence of the court.”

After a century and more of injustice and bias it is good to see a happy outcome for at least one woman caught up in the consequences of billeting the military in the parishes of the Falkirk district.