And its Designed Landscape

In 1754 the Elphinstone Estate near Airth was sold to Ronald Crawford, writer to the signet, on behalf of the trustees of John Murray, son of the 3rd Earl of Dunmore, to whom Crawford at once disponed them. Lord Elphinstone received for the lands and barony £16,000 sterling, with £200 of compliment. £10,000 was to be applied immediately to pay off the debts on the estate; and £6000 to be paid to Trustees at Lord Elphinstone’s death. Two years later John Murray inherited his father’s earldom, and renamed the estate in Stirlingshire “Dunmore” after his title.

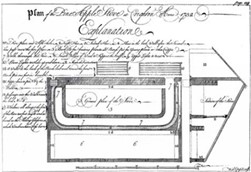

He set about improving the estate and had a large walled garden laid out on the south-facing slope 460yds (420m) from the old tower-house. The scale and grandeur of this horticultural complex reflected the importance of the art at the time and also the fashionable nature of architectural design then being lavished on them. The commercial worth of such gardens is shown by the following advertisement placed at a time when John Murray was serving as governor of Virginia:

GARDENS, With Hot-Houses, Green-houses, &c. to Let. To be LET for a short term of years, THE GARDENS of DUNMORE-PARK, with the Hot Houses, Green-houses, Orchard, and Shrubbery, and a curious new constructed bee-house, & c. these gardens were laid out in an elegant modern taste, a fine exposure, and a beautiful Pine-apple Summer house, with four rooms adjoining for lodging of gardeners. The gardens lye in rich country, near the banks of the Forth, and a populous neighbourhood for consuming the produce of the garden, being within one to three, four, and five miles of the towns of Alloa, Carronshore, Carron-works, Falkirk and Stirling; and there is a Coalliery on the estate, where coals may be had for the hot-houses so cheap as 3s per ton weight.

For particulars apply to Mr Robert Anderson seedsman, at the Cross, Edinburgh, or John Ogilvie, jun Esq, at Dunmore-park, who will show the gardens. (Caledonian Mercury 14 May 1774, 4)

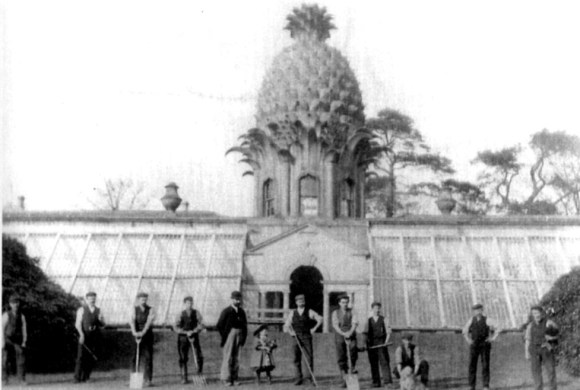

The famous Dunmore Pineapple had been built as a summerhouse in 1761 and it is interesting to see from the advert that the gardens were being kept up to date in the Earl’s absence by the construction of the bee-house. The enormous proportions and elaborate design of the summerhouse, which takes the form of the fruit, have rightly led to it being called “the most bizarre building in Scotland” and one of the most important of all the follies in Britain. The date of construction of the building is clearly indicated on the key-stone of the principal south-facing façade in ornate relief letters of a size appropriate for this grandiose building.

Above the datestone is an armorial panel which bears carvings that can be dated to shortly after 1803 (see below). This panel has been described as “later and clumsier” than the original design and yet its position in the pediment of the porch would seem to demand a coat-of-arms to fill it. And such was the case, for, by close examination, we can see that they were placed over an earlier carving which properly filled the space available. The original sculpture consisted of a demi-savage, wreathed about the head and loins with oak, holding in the dexter hand a sword erect Proper, pommel and hilt Or, and in the sinister a key of the Last. Above this is a slender earl’s coronet. These are the emblems of the Murrays of Dunmore.

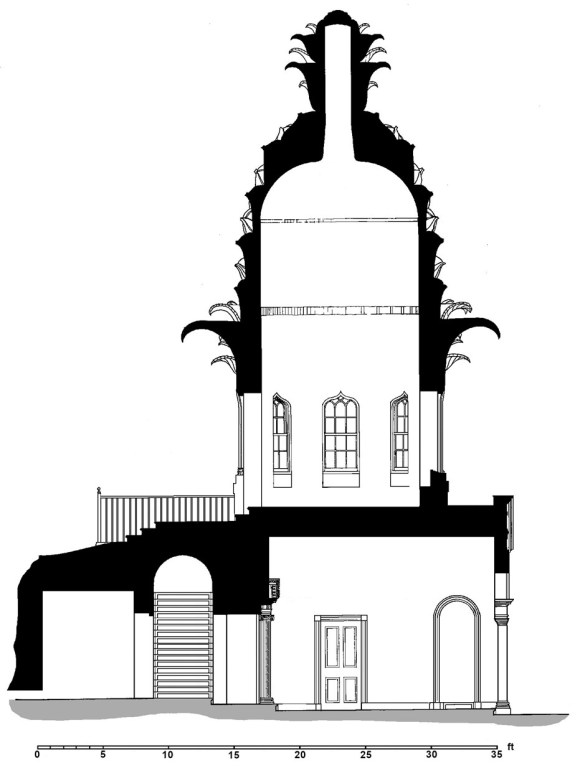

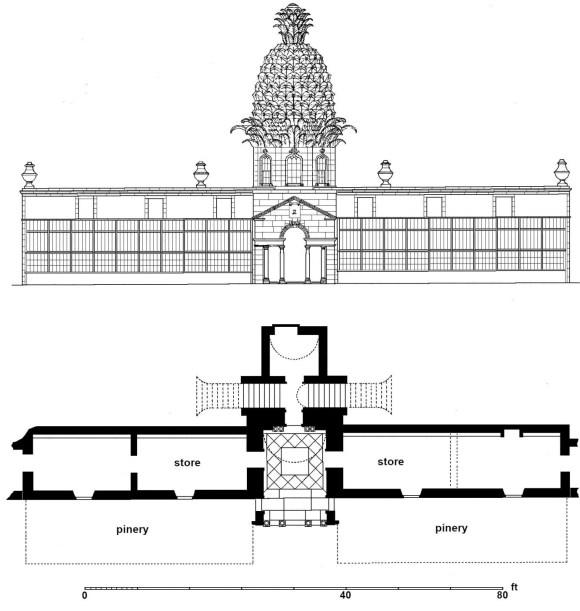

In 1759, Dunmore married Lady Charlotte Stewart, a daughter of Alexander Stewart, sixth Earl of Galloway, and it would seem that the planning of the Pineapple began at that time. A number of recent accounts of the Pineapple state that the upper-floor pavilion with its pineapple-shaped cupola was a later addition to the Palladian lower-floor portico, made after Murray’s return from his post of governor of Virginia in 1777; this was clearly not the case. Not only do we have the advert from 1774, but the very design of the lower floor was predicated upon being capped by a substantial structure. All of the rooms at this level have vaults. The building complex was planned and designed with the utmost care. It included the hot-houses for the growing of the pineapples. These flanked the main building and arched lateral openings from that portico gave access to them. Despite the unconventional design and the mix of architectural styles, the effect is harmonious because the pineapple and the portico are made of the same stone, ensuring a single colour from top to bottom, which would not necessarily have been the case had there been a delay of over a decade. The stone is a hard blonde sandstone which sparkles in the sunlight and can be found just a few hundred yards to the north-west of the Pineapple. Together the elements of the design draw the eye upwards in a single smooth motion. The geometry is well calculated. The width of the portico matches its height. The height of the building, from the bottom of the lower floor to the string course below the window sills of the summer-house (which correspond to the wall heights of the wings) is exactly one half of that from there to the top of the pineapple. Likewise, the height of the pineapple from the steps into the portico is exactly half the width of the structure and the wing buildings. Together, these elements, along with the four equally spaced urn-shaped chimneys, add to the sense of Classical order and harmony, made brash and up to date by the use of Gothic elements.

The layout of the hot-houses, the storerooms, the gardener’s dwellings, the chimneys, the portico and summerhouse capped by the beautifully–executed pineapple, present a delightful composition and demonstrate the skill of the architect. Recent historians have ascribed it to Sir William Chambers who worked on garden buildings at Kew and used similar themes – such as the chimney-heads taking the form of urns for the Casino at Marino near Dublin – but he was working in London at the time and it would be strange for such a remarkable building not to be mentioned in his writings. According to local tradition current a century after the erection of the Pineapple the stone mason responsible for executing the work was a local person of the name of Lees, who was assisted by two brothers of the name of Mitchell. They lived at the south end of Airth (Falkirk Herald 22 August 1861, 3; Stirling Observer 9 April 1857, 3). A further century on, this information had been lost, and Rev T Donaldson in 1961 wrote

“On Dunmore estate the ‘Pineapple’ was built by an Earl of Dunmore on his return from holding the governorship of Jamaica; the building, shaped like a pineapple, was designed by an Italian.”

There is no reason to suspect that such was the case, and it has led to erroneous suggestions that the masons were also Italians.

Pineapples were the flavour of the times. They were seen as a symbol of affluence and extreme wealth, of decadence and privilege, and being novel in the new age they displaced earlier such symbols. Stone pinecones had been decorating gardens for some time and may be found in Roman architecture. Their symmetry and natural beauty made them readily adapted as classical motifs, but in the eighteenth century the pineapple represented the brash new world with a nod to this earlier classicism. As early as 1722 stone pineapples appeared on gateposts in Lancashire (Beauman 2005, 115), and in 1767 William Wrighte’s influential book “Grotesque Architecture” shows pineapples on the top of a temple.

It is a Classical essay of novel conception, comprising a conventional portico-plan on which there is imposed a colossal stone pineapple. It and its associated structures provide a strictly symmetrical layout built into the hill slope and hence extend to two storeys. The south (ground floor) entrance takes the form of a Palladian Venetian or Serliana archway, incorporating Tuscan columns and a moulded arch with a dropped keystone. In the pediment, above the dated keystone, is the armorial panel already referred to.

Visitors who step through this archway into the barrel-vaulted vestibule face an elaborately framed doorway, flanked, on either side, by pairs of painted wooden Ionic columns, carved with great care, which display perfect fluting and entasis. The columns support a full entablature with a broken pediment. Lateral openings in the loggia – that part of the portico which protrudes from the garden wall – once led into the hot-houses. Doors in the side walls of the chamber give access to storage rooms hidden behind the garden wall. As the ground rises steeply to the north, the door at the inner end of the vestibule is consequently at basement level. Beyond the door a small vaulted chamber houses flights of steps which rise to right and left to the upper level. This part of the basement is bridged by a broad platform, flanked by heavy iron railings, which leads to the door of the summer house proper.

The boastful display of pineapples on gateposts was a way of letting the passer-by know that the owner was a person of substance, an in-your-face reminder of inequality, and not a sign of hospitality. Beauman (2005, 130) believed that the idea of a connection with hospitality was a construct of the 1930s:

“Right now, somewhere on America’s eastern seaboard, a hapless tour guide is pointing to one of these colonial-era representations of a pineapple as he or she relates the story of how the pineapple supposedly became a universal symbol of hospitality. It tends to go something like this: when sea captains returned from trade missions with the West Indies, they also brought with them a custom picked up from the natives. This was to place a fresh pineapple at the entrance to their home to signify to the neighbours that visitors would be welcome. The theory is that colonial gentlemen then sought to echo this custom in a more permanent form. Contemporary sources, however, make no reference to this story. In fact, it only gained currency in the 1930s as historic house museums sought to recreate an idealised colonial past.”

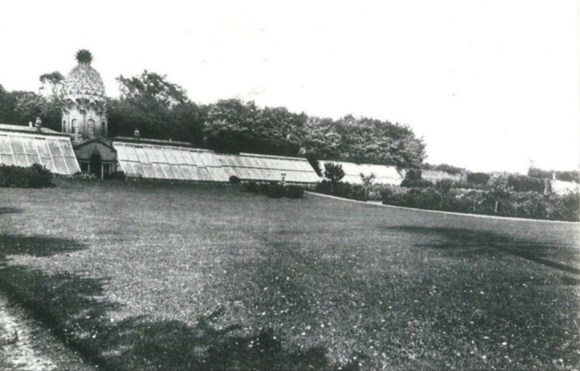

The Pineapple at Dunmore is the focal point of the walled garden and stands in the centre of the north wall.

This upper pavilion approaches the octagonal in plan but its sides are slightly curved. At each external angle there is a thick stem-like column, and in seven sides an ogival-headed window, with a door in the eighth. Within there is a circular chamber. Even the door and the panes of glass in the sash windows are curved, so as to match the curve of the walls in the room, which is just large enough to house a round table and some chairs. This chamber has a domical ceiling of stone, in the centre of which a circular funnel rises to the full height of the building. There may originally have been an upper floor or gallery, as joist-holes can be seen at a height of 14ft 6in (4.4m) above floor level. The outside of the dome or cupola takes the realistic form of a pineapple. The gothic ogee-arched windows terminate cleverly into the midrib of the leaves that curve outward in beautiful arches four feet wide. To either side the miniature engaged columns clasping the angles of the octagonal summerhouse behave in a similar fashion, creating an arched canopy around the window-heads. The massive leaves and fruits are cantilevered out from the carefully executed coursed masonry. The base of each leaf is higher than it appears when viewed from below, so that the rain water drains away easily from these higher parts to prevent frost damage. The stiff serrated edges of the lowest and topmost leaves and the plum berry-like fruits are all cunningly graded so that water cannot accumulate behind them. The structure is completed with a spiny-leafed crown.

The variety of pineapple used as the model was evidently the cultivar ‘Jamaica Queen,’ a variety with fiercely spiny leaves, outward projecting fruitlets and a perfectly egg-shaped outline tapering more towards the top. It stands about 37ft (11.3m) above the level of its threshold on the north; and, including the height of the portico, at least 54ft (16.5m) above that of the garden on the south.

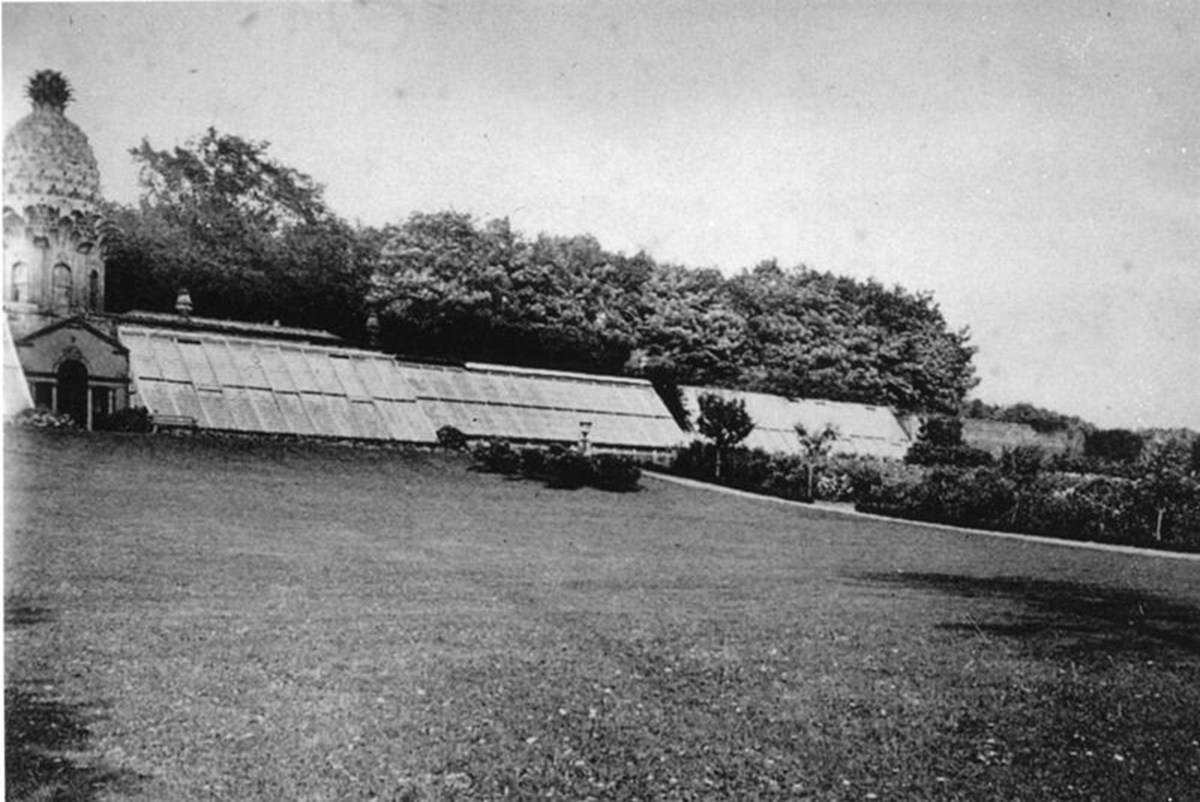

The wings to either side of the portico contained storage rooms on the ground floor and four rooms for housing gardeners on the first floor. They extend for a distance of 45ft (13.7m) and were faced on the south by hot-houses. The façade has a moulded wall-head bearing four large stone vases which disguise chimneys, and shows three windows to either side with backset freestone surrounds with rounded margins. These windows had been blocked up in later times but were re-opened to provide holiday accommodation. At the same time the four ground floor windows which let light into the stores from the hothouses were blocked up and harled over.

Other than William Chambers, there are several candidates for the architect who designed the Pineapple. Chief amongst these is George Steuart who designed and built a house in Grosvenor Place in London in 1770 for the 3rd Duke of Atholl, cousin of John Murray of Dunmore. In 1777 George Steuart was building greenhouses and lodges at Blair Atholl and Dunkeld for the 4th Duke. Architects used such family connections to obtain further commissions.

Another builder who worked at Blair Castle in this period was Robert Mylne who came from a renowned family of master masons near Edinburgh. From 1754 he spent several years on the Grand Tour and when in Rome he met Alexander Stewart, Lord Garlies. Upon his return to Britain in 1759 Garlies invited Mylne to make alterations on Galloway House. It may have been there that John Murray of Dunmore met Mylne because Murray had just married Garlies’ sister, Charlotte Stewart. Mylne designed a number of town houses and country houses, and a few public buildings. The first new country house was Cally in Galloway for James Murray of Broughton and was completed in 1763. Broughton had married another sister, Lady Catherine Murray Stewart in 1751. Mylne had met Murray of Broughton in Rome. Another early work for a private client in 1763 was for Edward Southwell, whom Mylne is reputed to have met in Rome. Mylne designed extensive stables and a kitchen garden complex for him at Kings Weston House near Bristol. Whilst there, he would have noticed the loggia designed by Sir John Vanbrugh on the Great Terrace that provided a long promenade into the woods beyond. It bears similarities to that at Dunmore.

From 1762 Mylne kept a diary of commissions and the Pineapple is not amongst them. That, however, may be because it was executed in 1761. The quality of the Pineapple’s masonry is of the standard to be expected of the Mylnes.

Rome had provided many of the connections that Mylne had been able to use in his early career. Rome may also have provided the inspiration for the concept of a giant pinecone or pineapple. The Fontana della Pigna or simply Pigna is a former Roman fountain of the 1st century AD which now decorates a vast niche in the wall of the Vatican facing the Cortile della Pigna. It consists of a large bronze pinecone almost 13ft (4m) tall.

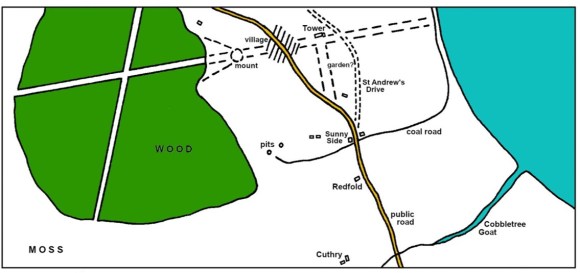

When John Murray bought the Elphinstone estate in 1754 the surroundings were very different from what they are now and we are fortunate that this was at just the time that William Roy and his team were surveying Scotland for the Great Map. The principal residence was at Elphinstone Tower. Despite being referred to as a tower it was in fact a substantial mansion. The tower had been built at the beginning of the 16th century but it had a later large three-storey stone wing on its west side and a smaller one to the south.

Up the hill to its west was the small village of Elphinstone and a tree-lined road connected them. Beyond the village this line of sight was extended by a circular mound, planted around with trees, and an avenue cut through Dunmore Wood. Its alignment continued to the coast on the east as a private avenue. Perpendicular to it was another such avenue southward (but not northwards as that would have taken it across the vertical face of the quarry used to obtain the stone for the house).

The public road southwards from the village to the burgh of Airth met the South Avenue at a place called Sunny Side (which became the site of the Pineapple), before going on to Redfold and Cuthry (basically on the drive to the present East Lodge). Roy’s Highland map shows the policy of the house in green with arable land to the north and east, and Dunmore Wood to the west. To the south and south-west was the old common (hence the name Cuthrie) and moss. The policy would have taken the form of old pasture and this early designed landscape would have given the surrounds of the house a pleasant parkland feel.

The 4th Earl of Dunmore set about enhancing the landscape of the estate. Elphinstone village was slowly removed, the occupants presumably being displaced to what had been Elphinstone Pans and was now Dunmore Harbour.

Dunmore Wood was enlarged, being extended eastwards with exotic planting. The roads were diverted. The north/south road which ran over the hill was initially re-routed to pass along the foot of the escarpment to the east of Dunmore Tower, along what today is known as St Andrew’s Drive. Later the Earl became the leading advocate for a new road by the Stirlingshire Roads Trustees to the west of Dunmore Park from Stenhouse through Dunmore Moss to Kersie and on to St Ninians which was put before Parliament in 1788. This was followed in 1793 with an application for a new turnpike road to the east along the line of the present A905, replacing St Andrew’s Drive – though it was well over a decade before it was built. So, in 1761 when the Pineapple was erected it was only 810ft (250m) from the main public road.

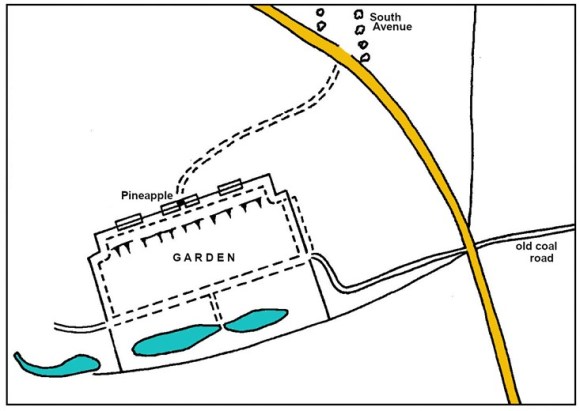

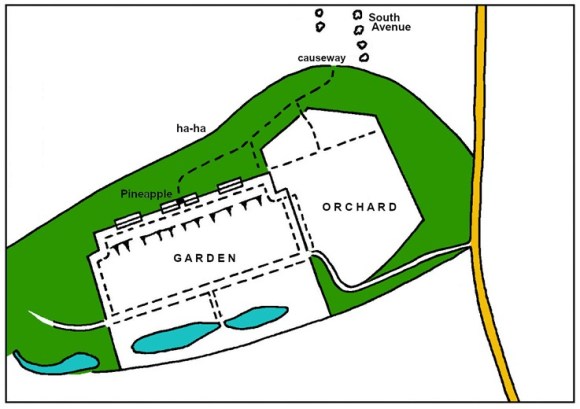

The old South Avenue pointed to where the eastern compartment of the walled garden now stands. That compartment is clearly later than the main walled garden (as shown by the butt join of their walls) and appears to have been fitted out as an orchard and therefore provided a buffer between the road and the pleasure garden proper. It may have been built after the Earl’s return from Virginia (he had been governor of New York 1769-1770 and Virginia 1771-1776). The field to the north of the Pineapple is surrounded by a ha-ha showing that it was still parkland, with provision for a shelter belt between it and the walled gardens. The ditch of the ha-ha has a causeway across it on the line of the South Avenue, thus privately linking the walled garden directly to Dunmore Tower. The area to the north of the walled garden was planted as a shrubbery, and species of yew, ash and rhododendron remain today, but are overgrown and have obscured the views out to the north and east.

The walled gardens were installed in open ground on a south-facing slope and hence the previous name of Sunny Side. Two old coal shafts are known in the area – one near the west wall of the main walled garden, and one 100yds to the west.

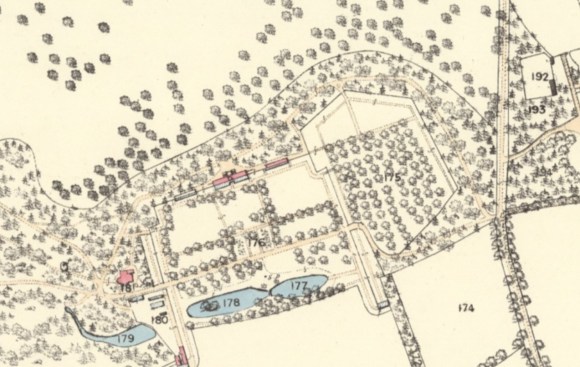

These were part of the extensive coalfield which had been worked for centuries and had been linked to the harbour by a coal road. They had been worked out and their associated features were now levelled. The new work was on an ambitious scale, the main walled garden being 6.3 acres (2.56ha) in size and the eastern or “Paddock” garden 3.4 acres (1.39ha). A certain amount of terracing was undertaken with a broad terrace created in front of the north wall of the main walled garden. Surprisingly, it was only between 1860 and 1895 that an ornate gateway was placed on its line in the east wall, and at the same time the axial path in the Paddock was moved south to line up with it. No such entrance was broken through the west wall.

As originally built, the west and east walls of the walled garden in the area of the terrace were quite low. From the 11ft high north wall they swept down in graceful curves leaving a wall barely 4½ft tall. A second similar step occurs at the foot of the terrace in the short perpendicular sections of the wall. Such features were common in the 18th century and can be found, for example, at Kinneil in 1710 and in the enclosure for the 1785 Bruce Monument in Larbert Churchyard. These elegant low walls reflect the recreational and leisure aspect of the upper part of the walled garden. Beyond the terrace the west and east walls are faced with brick on both sides and are much taller. They are designed to shelter the tender plants and to produce a micro-climate suitable for their growth. The brick walls are supported at intervals by dressed stone piers with moulded faces having a central vertical groove and swept sides. In general form they are like those that used to stand in the walled garden at Kerse House and which were dated to 1777. They also appear as gate piers for the west/east axial road, with an outwardly curving support for the gates – like a shallow engaged column.

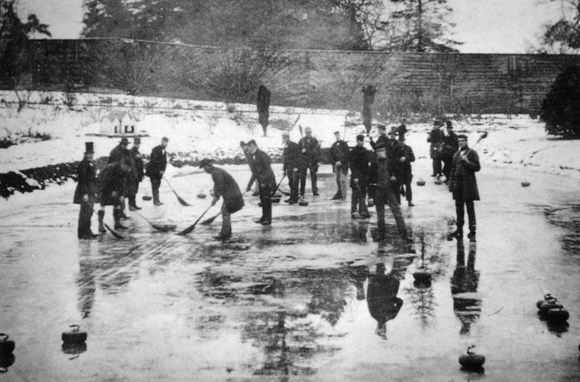

To the south a slow-moving stream was dammed to create a series of three ponds, the eastern two separated by a bridge on the central axis of the walled garden giving the perfect view of the Pineapple. At the north end of the bridge was a sundial. These ponds could be used for curling. They were prone to silting and the resulting shallow water favoured the freezing of the water. As was common there was no tall wall on the south side of the enclosure. Here an iron fence was placed on a dwarf wall.

The north wall of the walled garden was complex. In the centre was the summerhouse, 15ft (4.6m) wide, flanked by the gardeners’ houses, stores and pineries – 45ft long (13.7m). To either side of these were 60ft (18.3m) long sections of heated brick walls. Beyond these are 68ft of deeply recessed walls, and finally another 68ft (20.7m) of end walls on the main line. It will be noted that the sections increase in length to either end to compensate for visual attenuation when viewed from the centre. The heated sections were 11ft (3.4m) tall, capped with sandstone slabs. No structures are shown in front of these walls on the 1860 Ordnance Survey map but they were fronted by greenhouses by the time of the 1895 edition. They are of double construction and contain cavities through which hot air was circulated for the benefit of the espaniolated fruit-trees.

Pineapples were first grown in Scotland in 1732 and were a popular feature of many gardens in the second half of the 18th century. Initially they were grown using hot-beds where the necessary heat was generated by fermenting horse manure. The dung was placed in a deep pit, often brick-lined. It was not ideal as it heated violently at first but then cooled relatively fast. It was therefore often supplemented by heat from coal-fired furnaces fed through winding flues. These evidently existed at Dunmore as the 1774 advert states that:

“there is a Coalliery on the estate, where coals may be had for the hot-houses” –

The wall is here 3ft 3in (1.0m) thick and steps on the north side lead down to two furnace chambers beside which are small vaulted spaces for storing the fuel. The recessed sections of the north wall are taller and are set about 5ft (1.5m) back. They are not double; they were evidently designed to house greenhouses. The raggle of the south-facing roofs can still be made out on the return walls. The additional height suggests that they served as vineries and orangeries. Originally the walls to the west and east of the gardeners’ dwellings were only about 11ft (3.4m) tall, level with the string course of the central block. They were soon raised in height by a further 4ft (1,2m). The sections of heated walls have three rectangular recessed alcoves towards the top which may have been to take bee skeps in the summer. Alternating rectangular and square openings close to the tops of the recessed wall sections may, on the other hand, have been for ventilation of the glass houses.

greenhouses are mentioned separately. Placing the workmen’s dwellings against the back of the hothouse meant that the heat from the fires served both and they could be tended safely throughout the night. Fire damage was an ever-present risk. By the 1730s the horse manure in the hothouse had been augmented by tanners’ bark, which fermented slower and provided for more stable conditions. This would have been the method used at Dunmore and it is notable that the side porticoes into the pineries have steps showing that they had raised floors to accommodate the pits and flues. Unsurprisingly, Smollett in his 1751 book, The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle, has one of his characters denouncing pineapples as “unnatural productions, extorted by the force of artificial fire, out of filthy manure.” The front of the portico has small projecting stubs of masonry with rebates for the timberwork of the pineries which were an integral part of the original design. The glass and wood superstructure would have been much lower than those depicted in photographs in the early 20th century as the smaller space would have required less heating. Just as significant was the restrictive nature of the glass technology available at the time.

Three developments subsequently changed pineapple cultivation: hot water heating in 1816 (allowing the stove and its fumes to be located outside the hothouse or orangery), sheet glass in 1833, and the abolition of the glass tax in 1845. With these, glasshouses for pineapple cultivation became very large structures.

In 1775 Thomas Mouat had journeyed from the Shetlands to London to acquire furniture for the house that he was building. On the way he visited gardens and houses in the Edinburgh area in search of ideas. Fortunately, these included Dunmore and he provides us with the only early description of the Pineapple:

“…about 40 feet high and very curiously wrought in hewn stone, the leaves curving and hanging over very naturally. The space within it is octagonal and has an arched window in each square. Adjoining on each side are extensive greenhouses adorned by several huge stone vases of different forms, ornamented with festoon” (Mouat 1755), quoted in NTS 1992, 2).

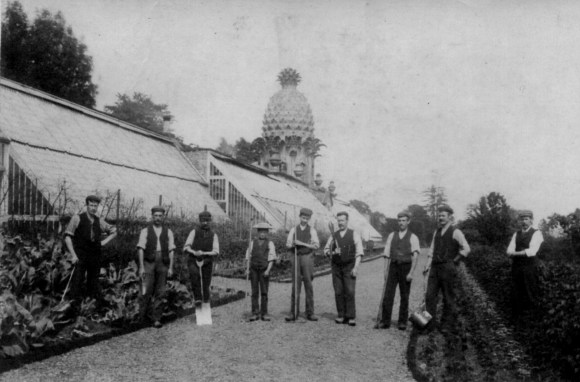

Some of the solid stone urns were still in the garden in the 1960s but were removed to other properties. They appear distantly in the photographs of the walled garden taken in 1917, which also show that there was a path running east-west across the garden, flanked on each side by herbaceous planting.

John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore, did not spend much time at Dunmore. From 1787 to 1796 he served as governor of the Bahamas. During his tenure many of the British Loyalists fled from America and were granted land in the Bahamas, tripling its population within a few years. The same phenomenon occurred in nearby Bermuda where its governor, Moses Benson, chose to have a pineapple put on his coat-of-arms in 1788. Many of the pineapples consumed in Britain came from that part of the world. Dunmore finally returned to Britain in 1796, but for most of each year he lived in the south of England. He passed little time at his seat in Stirlingshire. In July 1799 he wrote to his agent there to get the house ready for a visit:

“I propose to set off for Dunmore Park. I would wish you to have it all put in order for my reception… I hope the garden is on good order and appearance with all sorts of fruit” (Mitchell 2012, 7).

He died in Ramsgate, Kent, on 15 February 1809.

Lord Dunmore’s son, the future 5th Earl had been living in Glenfinart House in Argyll, from where he had written that :

“hothouse fruit … was sent every fortnight from Dunmore Park, where my father had no house, but an excellent garden.”

This situation changed when the son commissioned William Wilkins to design him a grand new house for Dunmore in 1820.

In 1803 George, 5th Earl of Dunmore, had married Susan, daughter of the 9th Duke of Hamilton. The massive armorial panel over the main entrance to the new house gives the Murray of Dunmore coat-of-arms parted per pale with those of Hamilton, but the datestone above the door on the side of the house has the emblems of Hamilton. The latter opened up onto the flower garden designed by the Countess of Pembroke. The Hamilton motifs were also set into the armorial panel at the Pineapple. These were a heart charged with a cinquefoil and the motto FIDELIS IN ADVERSIS (“Faithful in adversity”). First the existing decoration was chiselled flat with the face of the stone and then the new devices were pinned to it. Effacing his family crest would seem like a strange thing for the 5th Earl to have done after he inherited the estate from his father in 1809 and so it is possible that this event took place after 1892 when the property was acquired by Claud Hamilton. However, the bronze dial of the sundial near the pond also dates to this earlier period. It was made by John Russell who was one of Falkirk’s most famous watch and clock makers. The dial is inscribed “J Rufsell, Falkirk/ Watchmaker to H.R.H./ The Prince of Wales”. He had been appointed as Watchmaker to the Prince of Wales in 1811 and died in September 1817.

The fan-shaped espaniers can be seen on the wall in the background. To the left is what appears to be a model house which presumably served as a duck-house.

The opening of the new house in 1830 caused a reorganisation of the roads on the estate and with it a re-design of the landscape setting. A lodge was built near Cuthry at the south end of St Andrew’s Drive – rather confusingly called the East Lodge. A short distance to the north of the lodge the visitor was provided with a choice of very long approach roads. Proceeding straight on they would have passed to the east of the walled gardens and below the folly-like ruins of the old towering baronial castle. Continuing north they rounded Mount Charlotte to the main gateway. Alternatively, they could turn left and see the wall garden in all its grandeur on the right. This gave them a view along the central access of the garden complex and to reinforce it projecting wings were built onto its southern corners, consolidated by outbuildings, further strengthened by lateral shelter belts to guide the eye. This route took them through the huge wood and passed a small pond and finally the visitor came to the main gateway.

Dunmore Park House became a family home and was often occupied by the Murray family. In 1876 the Prince of Wales stayed there. Dunmore Park was also occasionally visited by botanists and members of the public, one of whom left this account in 1859:

“It is under the hot frames of course where anything worth seeing is to be seen. The first is devoted to the rearing of young vines. The system adopted by Mr Carmichael for the better production of the crop is by planting the muscat of Alexandria and the Black Hamburgh alternatively. A richer profusion of fruit could not be desired, and the enterprising superintendent has evidently a special genius for this profession. The Stirling Castle peach, which is grown in an adjoining house, is beautifully trained, and Mr Carmichael, we understand, was the first last season who had the peach in the London market. Among the flowers under glass are heaths, camellias, geraniums, and fuschias, and of rarer kinds we may note the “holy ghost” plant, or, as it is classically named, the Peristeria elata, and the Begonia Rex. We had also the pleasure of seeing and tasting the new fruit Eugenia Ugni. The berry is of a reddish hue, about the size of a black current, and has the flavour of the strawberry. It only required the protection of a cool greenhouse, and the plant generally is not unlike the myrtle. The “laying out” of the kitchen garden is a masterpiece of order. Its extent may be 10½ acres, and the ground is bounded on the south by what is reserved as a curling pond. If this severe and congelating weather continues, there will be a few roaring games played by the bye. Somehow we have a particular liking for the echoing music of the ice, as the curling stone bounds along its glassy surface, and for us there is a practical poetry in the artistic sweep of the broom” (Falkirk Herald 27 October 1859, 3).

Two accounts of a visit by the Stirling and District Horticultural Society in 1908 will be found in the Appendix.

William Carmichael was the head gardener and came from Comrie. In 1863 he received the appointment of gardener to the Prince of Wales on his new estate of Sandringham.

Only one recorded incident of the outbreak of fire is known at the Dunmore walled garden. One morning in March 1860 George Burden, coachman to the Countess of Dunmore, was passing the buildings adjoining the Pineapple when he perceived some smoky fumes issuing from the fruit room. Acquainting Mrs Ritchie who lived at the nearby lodge, she immediately alarmed the gardeners, who fortunately were at work in the garden and through their endeavours the fire was confined to the fruit room, and speedily subdued before much damage was done. The fire had originated from a beam of wood which had ignited from the heat of the vinery flues (Stirling Observer 22 March 1860, 3).

The walled gardens were productive and were worked even when the Murray family were resident elsewhere, sending fruit and vegetables to wherever they were required. This demanded a moderate staff of gardeners. According to one source there were 22 gardeners and 8 gamekeepers at one time (Callendar Advertiser 18 August 1934, 3), though the 1881 Census only shows that the following were present at then:

- Morris Fitzgerald, aged 55, gardener, Dunmore Gardens.

- Alexander Primrose, aged 14, apprentice gardener, Dunmore Square.

- William Bennett, aged 17, gardener, Dunmore Square

- Thomas McCall, aged 30, gamekeeper, Dunmore Stables.

- Duncan Shaw, aged 28, gamekeeper, Dunmore Stables.

There were also a couple of foresters.

The greenhouses had to be maintained and kept up to date. The latest fenestration covered almost the entire south façade of the north wall to either side of the central pavilion and so the windows in the gardener’s quarters were blocked up. With the increased availability of plate glass and its lower price additional greenhouses were added to either side.

By the end of the 19th century the grandiose house of 1822 was little used and the family favoured its other properties. In 1887 Claud Hamilton of Barns and Cochna, Dumbartonshire, took a lease of Dunmore Park for five years, at the end of which he purchased the property. His family crest was the heart charged with a cinquefoil, and so it may have been that he altered the pediment of the pavilion at the Pineapple. He and his family became heavily involved in the local community but he died in 1900 and his Trustees sold the estate in lots in 1917. It was bought by the Jones family from Larbert who had businesses in ironfounding and home grown timber. In the 1950s the walled garden was turned into a commercial market garden. After it failed and was abandoned the Earl and Countess of Perth purchased the Pineapple and the walled garden in 1968 intending to turn it into a house. They had plans drawn up for additional wings to the north of the gardeners’ houses. The architect employed was Stewart Tod of David Carr Architects in Edinburgh. They decided not to go ahead with this and instead they gifted it to the National Trust for Scotland from whom the Landmark Trust took a lease in 1973. It employed Tod to carry out a scheme of renovation.

The site had been severely neglected and the buildings on either side of the Pineapple were deteriorating in a bad way and overgrown. The vegetation had to be removed. The three remaining urn-shaped chimney pots were taken down and all of the doors, window frames and the carved wood entablature behind the portico were removed and stored for later use. New joists and flooring were put in and the roofs were rebuilt and recovered using the best of the old slates with new ones to match. All of the timber lintels were replaced and the walls were made good up to the eaves with the coping stones carefully reset. The fourth decorative chimney pot was found broken into many fragments, but these were all carefully gathered and stuck back together to join the other three. The portico roof was likewise re-slated with a mix of old and new slates and the cornice was carefully taken down, re-bedded and reset because it had become displaced. Stonework to the north entrance and the steps was reset and the metal railings repaired and re-fixed. The walls and vault were treated for damp and waterproofed and re-plastered. The wooden Ionic columns and the broken entablature were restored and the stone slab floor was overhauled with paving from Natural Stone Quarries(UK) Ltd. Amazingly, the stonework of the Pineapple was in remarkably good condition – all the joints were raked out and re-pointed and the whole fruit was cleaned by hand with just water and a churn brush. Inside, the existing windows were repaired and others were replaced to match exactly. The stonework and plasterwork was cleaned and redecorated and window seats were supplied and fitted. Finally the holiday accommodation was formed in the two wings – bedrooms, bathroom, sitting room and kitchen.

The garden was a jungle, covered with rosebay willow herb. The Scottish Tourist Board gave a grant towards its restoration, and the area was cleaned and prepared for the trimming and grading of the slopes. It was seeded in the autumn of 1974 with the first cut the next spring. The South Pond was cleared and put in order and the perimeter railing re-erected. The stone doorway in the east garden wall was also rebuilt and the walls were repaired where necessary with 14,000 bricks made to match by the Swanage Brick and Tile Company. A tree planting scheme was carried out based on a formal orchard layout. As part of the above-mentioned grant it was agreed to build public toilets to the rear of the north wall of the garden towards the east end. This was done in 1975 by converting a lean-to garden store on the back of the north wall, but due to vandalism and maintenance problems they had to be closed. From 1977 to 1980 a local farmer paid to graze some of his sheep on the main lawn which also helped to keep the grass down. The fence that had kept the sheep off the west/east axial road was removed in 1984. At the same time the garden connected with the holiday accommodation to the north of the Pineapple was laid out. Planting around the edges of the main walled garden was delayed until 1990.

In 1988 a single-storey cottage was built to the east of the car park to house the Landmark Trust groundsman. It is in neo-vernacular style and from 2024 it too became available as a holiday home.

The Pineapple is a remarkable building and a fine tribute to the skill of the architect and masons. It is rightly famous and features on the front covers of two authoritative works – “Scottish Garden Buildings” by Buxbaum, and “Follies” by Headly and Meulenkamp. It remains an enigma and is well worth a visit – and then another.

Here, where the breezes rustle by, -

Here, where the cheerful sunbeams play, -

Sit down, and learn the history

Of that lone garden’s palmy day.

No gleam did e’er its shades rejoice

From silken robe or brilliant flowers,

It echoed not to Pleasure’s voice,

Not took gay gifts from Summer hours:

Yet royal eyes, with nicest choice,

Had ordered all its walks and bowers,

Had grouped the laurels, taught the pine

And ilex where to strike their root,

Where arbutus should dimly shine

With clustered mockeries of fruit

And where the savine’s spicy fan

Upon the velvet turf should sweep;

Had traced the pathway’s mazy plan,

Which round the jutting shrubberies ran

To nooks of shade, as caverns air,

The cedar closing with the yew;

Nor sunshine ever slanted there.

Nor ever noon could dry the dew,

And lawn, and path, and dim retreat

Were strange to all exploring feet,

Save of one dreamy, musing man,

Who, high in birth, and rich in mind,

Born to control and lead his kind,

To lesser men the work resigned.

His phantasy this shrine had wrought

These dedicated haunts of Thought,

Where he might bathe his soul at ease

In the still mist of the reveries;

And all that through the outer sense,

The unconscious mind might influence

In brooding shade and mossy lawn,

And odours from the shrubberies drawn,

Whose warm wealth steeped the atmosphere,

As ministers were gathered here.

(by Mrs E Hinxman, wife of the Rector of Dunmore Episcopalian Church – 1856)

Sites & Monuments Record

| Pineapple, Dunmore | SMR 186 | NS 8889 8854 |

Bibliography

| Beauman, F. | 2005 | The Pineapple; King of Fruits |

| Buxbaum, T. | 1989 | Scottish Garden Buildings: from Food to Folly. |

| Donaldson, T. | 1961 | ‘Parish of Airth,’ Third Statistical Account. |

| Headley, G. & Meulenkamp, W. | 1986 | Follies; a Guide to Rogue Architecture in England, Scotland and Wales. |

| Mitchell, A.E | 2012 | Dunmore. |

| Mouat, T. | 1755 | Tour of Edinburgh and London. |

| N.T.S. | 1992 | The Pineapple Management Plan 1992-1997 |

| RCAHMS | 1963 | Stirlingshire: An inventory of the ancient monuments. |

| Whitelaw, J.F. | 1990 | Follies. Shire Album 93. |

| Wrighte, W. | 1767 | Grotesque Architecture. |

Appendix

The Garden in 1908

Bridge of Allan Gazette 11 July 1908, 8:

“Stirling and District Horticultural Society – ….. The seven miles drive the Carse was much appreciated and on arriving at the Airth Road entrance to Dunmore Park the party was met by Mr Wood the ever genial head gardener, and his assistants, who took the company in hand towards the garden entrance. The walled garden, which is ten acres in extent, is entered by a magnificent broad central walk, terminating at either end with wrought iron gates. Parallel with this walk on either side are two magnificent herbaceous borders, planted in large masses of all that is good, useful, and effective. Time did not permit of taking notes of the many plants seen, but one in particular – Delphinum, King of Delphinums, was particularly admired. Proceeding to view the glass structures, the first house entered is of the old “lean to” type, and is given up entirely to one vine. The main rod is planted at one end, and is trained up the roof from this at regular intervals. The length of the main rod is 94½ feet, age 48 years, and number of clusters 197, all being serviceable bunches. The plant structures were next visited, and, as may be imagined, everything that is good is grown in large masses. A little of anything is of little value here. In one house a large batch of zonale geraniums were particularly good, the best varieties only being grown. In warmer quarters were seen a large batch of bergonias, Gloire de Sean and Plumbag’s Rosea, both of which Mr Wood finds indispensible for winter decoration, and which were looking healthy. Another house was filled entirely with carnations, which were marvels of good cultivation. This, being Mrs Hamilton’s favourite flower, is always in request. These are but a few of the many useful plants grown here. Entering a long range of “lean to” houses, the company found heavy crops of peaches, grapes, and figs, the latter showing a good second crop. On leaving the glass structures, the party were attracted by several large beds and borders devoted entirely to the cultivation of one flower for cutting purposes. Here were gladioli, the bride, anemones, carnations by thousands, and other varieties too numerous to mention. A magnificent bed of violas was specially attractive, with “Fighting Mac” in the front rank as usual. Here the chief specialists of the party had an opportunity to compare results, the entire collection being plunged in the borders, and every facility given for examination. No doubt we shall have the pleasure of their further acquaintance at the November Show in Stirling. Glancing over the vegetable crops, their quantities reminded one more of a market garden than of a private place, there being brakes of one variety from a quarter of an acre upwards. We noted particularly about a quarter of an acre of lettuces. Good cultivation and a constant succession is the order at Dunmore. Fruit all over is a fair crop, especially in a large orchard…”

Alloa Advertiser 25 July 1908, 3:

“On arriving at the south entrance the party was met by Mr Wood, the genial head gardener, and his assistants, who conducted them over the somewhat extensive gardens and grounds. Everything is on a large scale at Dunmore; walled-in kitchen garden and orchard (10 acres), large trees, large vine, etc., in fact almost everything is big except Mr Wood’s Yorkshire terrier, named “Wee Macgregor,” which only weighs 3½ lbs. The interesting little creature welcomed the company, and also took part in all the afternoon’s programme.

Immediately on entering the large walled in kitchen garden, one was confronted with a big broad walk with herbaceous borders on either side, at the back of which are climbing roses galore. A very old favourite – Blairii No. 2 – so seldom seen now-a-days, early attracted one’s attention. This variety has a colour of its own. The perennials were beginning to give of their best, those most conspicuous being- Carduus heterophyllus (deep rose thistle-like heads of flowers), Kelway’s paeonies in great variety, Delphinums, Lord Balfour, and King of Delphinums. The latter is a semi-double, gentian blue and plum, with a white eye, one of the newer varieties, the most handsome of an imposing class of plants. Lychnis haagaena, senecis doronicum, Japanese iris, cephalaria tartarica, etc. leaving this, we entered a house 120 feet long, almost covered by one vine. Though it is not so large as Lord Breadalbane’s specimen at Auchmore, still, it must be ranked as one of the largest in Britain. It was planted in 1866, and one of the company, Mr Adam Ferguson (late of Woodville), knew it when growing in a cutting pot. This house is a lean-to one, the back wall – outside of course – was covered with ivy. Two years ago this was taken off, and wall gardening has now taken its place. We then had a look in at the large, clean, well-lighted potting shed. What a pleasure to work in such a place compared with the dingy, damp places which have to do duty for potting sheds at so many establishments. The extensive glass structures – 16 in all – were next visited. The greenhouse contained the usual flowering plants, palm house with a goodly array of serviceable palms. A fine batch of orchids were also accommodated here on the front stage. Begonias (Gloire de Seaux), Plumbago rosea (in pots), roses, carnations of all sections, all grown in quantities for cut flower work. A speciality is made of carnations, these being Mrs Hamilton’s favourite flower. Mr Wood willingly gave selections of the best in their respective sections, the border varieties were: Duchess of Fife, Mrs Muir, Salamander, Mrs Daniells (bright scarlet), and Dunmore seedling – pure white flowers borne on stiff erect stems, most useful for decorative work. Every autumn 1400 of these border varieties are planted out. A border of bedding violas and pansies was most attractive, Hector M’Donald in the centre, Cosmos, and Holyrood being most conspicuous. Good serviceable bunches of grapes were to be seen in the vineries, white peaches, nectarines, and figs (second crop), were truly grand. In a season like the present, when peaches are so deficient a crop, Mr Wood deserves commendation. It was interesting to see the exact spot where the original Stirling Castle peach tree – raised at Dunmore – was grown. The original tree and its successor have fallen victims to the law of decay, their places being filled by a vigorous young representative. Tomatoes, cucumbers, and melons are in prime fruiting condition. For cutting purposes, there are large beds of gladioli (the bride), old double Scotch rocket, montbretias, anemone, St Brigid, etc., borders of carnations, and so on, all grown from a utilitarian point of view. Two rows of that newer importation – the logan berry – were in splendid condition; this new fruit is a great success at Dunmore. Large breadths of good conditioned vegetables, such as peas, Brussels sprouts, etc, were also much in evidence. Water lilies in the pond at the lower end of the garden also appealed to many. The varieties were the common white – Nymphea alba – pretty, chaste flowers, and a yellow variety which grows too luxuriantly, as it is gradually killing out the white variety. Every liberty was given the members to inspect the chrysanthemums, which will, no doubt, make their mark, as formerly, at the November shows.”