Early landing places on the middle stretches of the south shore of the Forth were numerous as the vessels were small and of relatively shallow draft. Places where the sleeches were narrow and where streams scoured channels through them were favoured. It is almost certain that the Roman fort at Carriden would have had a landing place at the mouth of the Muirhouses Burn. In the medieval period the bay at Kinneil was favoured (see Kinneil House).

By the late 15th century Bo’ness was the home of a community of skilled seamen and in 1490 Sir David Falconer was described as a “brave cavalier and skilful mariner” of Borrowstounness (Ewart & Pollock 2006, 2). The small natural promontory at Bo’ness (“ness” means promontory) was in an advantageous position to form a landing place as the mudflats were narrowest there and the water correspondingly deeper. Our first reference to its use was in 1544, during the Regency of Arran who built the palace at Kinneil, when a report on the harbours and landing places in the Forth noted:

“Kyniell – by este Kallendray (Callendar House), a myle from the shore and good landinage with botes at a place cauled Barreston”.

(Salmon 1913, 27)

The earliest facility here was a simple causeway, the remains of which according to Salmon were discovered when enlargements and improvements at the harbour were made in the 19th century (ibid, 22).

On 19 October 1565 the Privy Council appointed Patrick Cruming of Carriddin:

“keeper of the haven of Borrowistounness, and all the bounds betwixt the same and Blakness for watching the passage of any of the enemies of their Majesties.”

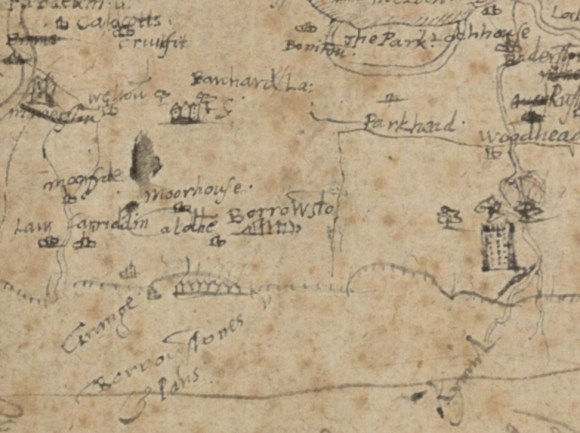

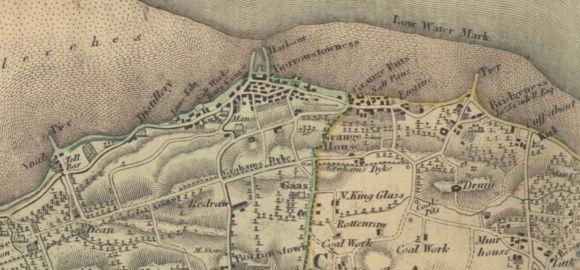

By that time Bo’ness was already a flourishing town and a mercat cross is mentioned there as early as 1573. This was one of the first areas surveyed by Timothy Pont in around 1575 for his map of Scotland and his surviving draft shows north at the bottom of the page. The great tower at Kinneil House is well illustrated with a coastal bay to its east, as are the sea-facing gables of the pan-houses at “Borrowstones.” These were then located at the Ness with a second shallow bay between them and Grange. One of the pans was discovered under Dymock’s Building during recent reconstruction work.

Blackness was the port for the royal burgh of Linlithgow and it jealously guarded its trading rights. It was clearly concerned about the increasing trade at Bo’ness and attempted to stop the growth of the town. This often placed the magistrates of Linlithgow in conflict with the powerful Hamilton family of Kinneil who acted as the sponsors of the upstart port. Sometime around 1600 the king had granted to Borrowstounness, among other privileges, the liberties of :

“ane frie port of packing, peilling, lossing, laidning, and selling of staple wairis, sic as skynis, hydis, wool, wyne, wax, and all uther kynd of merchandice and wairis usit to be sould and bocht within any burgh Regale within this realm, with all customes and ankerages belonging to a port and heaven of a frie burgh.”

(R.P.C. 6, 289-90).

A formal complaint was then lodged by the provost, bailies and community of Linlithgow against this grant, stating that it was to the

“grite wrak and decay of thair burgh end heaven (Blackness) quhilk is biggit and repairit be thame for saiftie of schipis and boittis upoun thair grit expensses.”

The matter was taken under consideration. As it happened, the Privy Council discharged Bo’ness from being a port on 27 April 1602, along with numerous other places, because of the smuggling that was rife. One can well imagine the Linlithgow agents reporting on the activities of these smugglers. The ban did not last long and commerce continued to increase at Bo’ness.

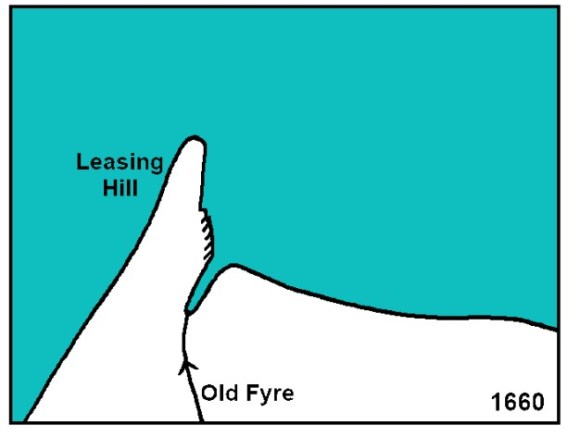

The east side of the ness provided the best shelter for the vessels and the ships naturally favoured it. In 1650 the Duke of Hamilton feued part of the ground at the landward end of the ness to a merchant named William Thomson who had recently erected buildings there. The description of the bounds of the property is interesting –

“near the port of the same, on the hill called Leasinghill, bounded by the rivulet called the old fyre coming from the old coalmine of Bo’ness on the east, the lands of the said noble duke on the west, the houses of James Gib and Peter Stevin on the south, and the sea on the north, containing in length from east to west fifty feet of ground, with free entry and exit to the east”

(notes kindly provided by Dr E Dennison).

.

The majority of the inhabitants of the town made their living from the sea – as sailors, fishermen, ships’ carpenters, ropemakers, provision grocers, merchants, carters, and the like. Coal and salt were among the early exports, chiefly to Holland and the Baltic. When the Union of the Crowns took place, in 1603, a great impetus was given to the commerce of the country and the infant port evidently shared in it. This prosperous trade induced a number of rich merchants from the west, shipowners and others, who saw possibilities of great developments in the place, to acquire property or to reside here. The town and population therefore rapidly increased. These were the days when a Glasgow Customs officer was appointed to Bo’ness “on promotion” (Salmon 1913, 22).

.

The Seabox Society of Bo’ness was founded in the late 1620s to provide money for the widows of seamen and for the upkeep of those who fell upon bad days. In 1640 the Society gave itself a new bond of erection in which it laid down that each seaman would contribute 8d in the pound of all their wages and profits. Sound investments were made in property which produced steady rents and made the Society very influential in the town’s affairs.

“Leasing” probably derives from Old Scots word “lesche” meaning anything long of its kind (Concise Scots Dictionary), which would suitably describe a promontory. Having the exit to the east would have made it ideal for access to the harbour and from the beginning the house incorporated a yard and stores. However, the most revealing feature of the sasine is the existence of an artificial waterway draining the coal pits on the high ground to the south. This would have scoured the east side of the ness, removing silt and providing deeper water for the ships. By 1662 the description had changed. Now there was :

“grund callit the waist grund on the east”

(Dennison).

This waste ground must have been the silted up bed of the old watercourse. A road called “the Hie Streit” is mentioned on the west which would have led to the shore and landing place. It is possible that the promontory was artificially lengthened at this time for in 1688 the property changed hands and the Leasing Hill, rather than the sea, bounded it on the north.

Already by 1656, when Tucker made his report for Cromwell, Bo’ness was considered to be the second most important port in Scotland:

“The next port is Burrostonesse, lyeing on an even lowe shoare on the south side of the Firth, about the mid way betwixt Leith and Sterling. The towne is a mercat towne, but subservient and belonging (as the port) to the towne of Lynlithquo, two miles distant thence. The district of this port reacheth from Cramond exclusive, on the south side of the Firth to Sterling inclusive, and thence all along the north side of the same Firth as farre as a little towne called Lyme-kills.

“This port, next to Leith, hath of late beene the chiefe port one of them in Scotland, as well because it is not farre from Edinburgh, as because of the greatt quantity of coale and salt that is made and digged here, and afterward carry ed hence by the Dutch and others, and the comodityes some time brought in by those Dutch who, avoyding and passeing by Leith, doe runne up the Firth, and did usually obtayne opportunity of landing theyr goods on either side in theyr passage, the Firth a little above Brunt Island contracting and running along in a more narrowe channell. There are constantly resident at this port a collector, a cjiecque, and some foure wayters to attend the coast and Inchgarvy.”

The continental connections were problematic as far as infectious diseases were concerned. From time to time it was necessary for the Privy Council to stop foreign ships from visiting. Notwithstanding their orders prohibiting ships from Holland entering any of the harbours or ports of Scotland until they had lain in quarantine for forty days, several ships, after being debarred from entering the harbours of Queensferry and Borrowstounness in 1663, had landed at Grange and other places nearby to the endangerment of the country. Therefore the Lords gave:

“warrand, power, and command to the magistrattes of Linlithgow and Queensferrie, and to my Lord Duke Hamilton and his baylie of Kinneil, or any of them, to debar and stop the entry of all shipes, or landing of persons and goods from Holland at any place betwixt the saids two ports of Queensferrie and Borrowstounnesse.”

(R.P.C.).

On 2 February 1664, the Privy Council considered a petition by Andrew Burnsyde, John Dunmore, and Robert Allan, shipmasters in Borrowstounness; along with Thomas Fleming, Edward Hodge, and Andrew Duncan, shipmasters in Grangepans, craving for a relaxation of the prohibition. In support they stated that upon information from Sir William Davidson, Conservator in Holland, and Mr. John Hog, Minister at Rotterdam, together with his elders, the plague was much arrested in Amsterdam, and that there was no infection for the present in Rotterdam. The Lords in this case ordained that the quarantine should only be “Threttie dayes after they come to the porte.” The magistrates of Linlithgow and Queensferry and the Duke of Hamilton’s bailie were to see the quarantine punctually observed :

“by making of the said shipmasters and their company keip themselves within ship boord in the road, setting of watches for that purpose, and preseryving of such other orders as they should think expedient”

(R.P.C., 3rd series, vol. i, 492).

The pestilence raged throughout most of that year and some of the various actions necessarily taken will be found in the appendix below.

King Charles II, in January 1668, granted a charter in favour of Duchess Anne and her heirs, creating the lands and baronies of Kinneil, Carriden, and others, and the town of Borrowstounness, into a Regality, and naming the town to be the head burgh of the Regality. The following year an Act of the Scots Parliament, doubtless on the supplication of the Duke and Duchess, embodied the charter and, in addition, confirmed the burgh in the privilege of a free port and harbour.

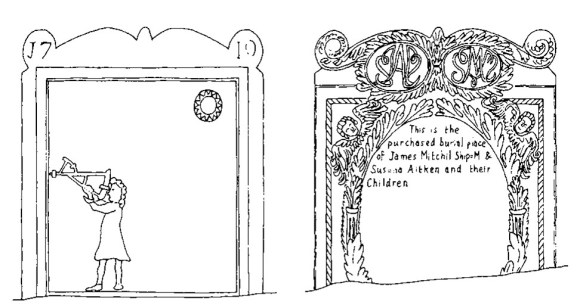

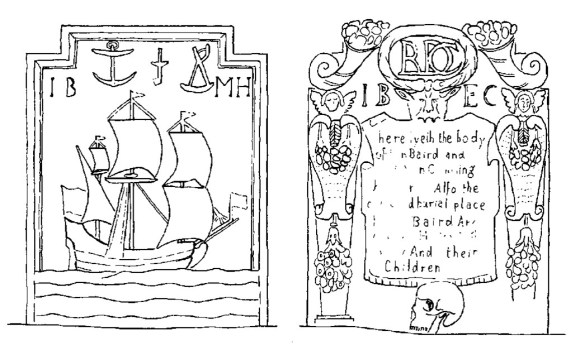

The sailors were an important part of the Bo’ness community and contributed to the various institutions in the town. Through the Sea Box Society they put up most of the money needed to build the church in 1638. The building was long and narrow and of a single storey with a loft and stair leading thereto for the accommodation of the “skipperis and marineris“. Later a gallery was added for the Duke and Duchess of Hamilton and their tenants; and later still another for their colliers. A proposal in 1761 to install a second loft above the “sailor’s” loft was rejected by the representatives of the seamen as it would have obscured the two large windows behind the seating. The nature of the maritime trade meant that the sailors were away for much of the time and this was taken into account by the Church, as illustrated by the Kirk Session Record for 20 July 1708:

“ye Minister presenting to them that the fleet now being at home and several of the seamen very desirous as he found by conversing with them that the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper should be administrate before they again went to sea, they also said that they had been deprived of this Ordinance these last two times it was given here. Which the Session considering, they without a contradictory voted the same to be administrated Sabbath come a day twentie days being August twentieth and second and accordingly to be intimated Sabbath next.”

The behaviour of the men was sometimes called into question, with drink and violence featuring large. Fornication is often mentioned in the Session records and every sector of society came in for scrutiny. Most of the practical problems of fornication that the Kirk Session had to resolve were due to troops being billeted in the town and then moving on. Mariners were usually only temporarily absent, unless they belonged to another port:

“After Prayer Compeared Marcy Hamilton who says she came about seven months hence from Stirling & says that she was Four days old at the Battle of Culloden and that she is now with Child & that the Father of that Child is one John Stirling Captn of a Rice Ship belonging to Dundee & who shifted a Cargo of Rice here about Four months ago being about eight days before the Mason Bale. Being further asked where he got her with Child she answeared it was in his own Cabine betwixt ten & eleven O Clock at night, being asked what took her down to his Ship or Cabine at that time of night she answeared that Alexn Adams Wife whose Servant she then was sent her down with linnens for Captn Stirling being asked if she saw any Body but Captn Stirling about of the ship she answeared non but a Boy. The Session considering that Captn Stirling leaves in another Parish and is abroad delay this matter for some time”

(9 October 1759).

In the 1690s there was an average of about twenty ships based at Bo’ness, with another four at Grangepans. In 1691 HM Customs recorded 47 vessels arriving from outside of the Bo’ness precinct and 66 departing, the apparent discrepancy arising from foreign ships discharging their incoming cargoes elsewhere and returning home with a shipment of Bo’ness coal or salt. Of the 98 vessels leaving Bo’ness that year, ten were laden with salt and the rest with coal. The Seabox Society’s records suggest that each of the Bo’ness boats carried a crew of eight or nine seamen besides the captain. Allowing for the fact that not all of the ships were away at any one time, this indicates the presence of 150-200 mariners based at the port (Cadell 1988, 9). These were prosperous years and a play of 1692 opens with the line “What a Devil hath brought you hither?” To which the answer was “A Borrowstounness ship and a good Protestant wind.”

Imports at this period included paper, dried fruit, hats, madder, soap, and tar, most of which were destined for onward transport by road. One of the luxury items consumed locally in small quantities was green tea. Most of these items incurred a tax and so it is not surprising to hear that smuggling was still rife. Reverend John Brand lodged with the Customs Collector when he first moved to Bo’ness in 1694 and so became only too aware of the lying, deceit and violence involved. He wrote in his diary :

“I was not long in the place when thoughts of merchants running their goods to save the duty, shipmasters swearing at the Customhouse that they had not broken bulk and had given a just and true report of what goods were imported, and their behaviour afterwards in securing the goods so run and bringing them home to their own houses and underselling the fair trader… were very troublesome and uneasy to me… I have oft spoken against these sinful practices but I fear with very little success”

(quoted in Cadell 1988, 13).

He realised that it was a way of life in which nearly everyone in the town was involved. Even those not acting directly in these illicit procedures enjoyed watching the pitched battles between the tidesmen and soldiers on the one hand and the smugglers on the other.

Seamen were always wanted by the navy and Bo’ness being so close to Edinburgh provided a ready pool. In 1664 the Earl of Linlithgow obtained “Six men out of Cuffaboutpannes and Grange, and thirty-four men out of Borrowstounness” on behalf of the Privy Council. Over the decades many Bo’ness men were pressed into service. On 7 July 1708 Mark Stark wrote from Bo’ness to say that one of his grace’s tenants has been pressed for the ship the Squirrel, but feared that it was too late to use the Duke’s influence to intervene as the ship had already gone (Hamilton Papers).

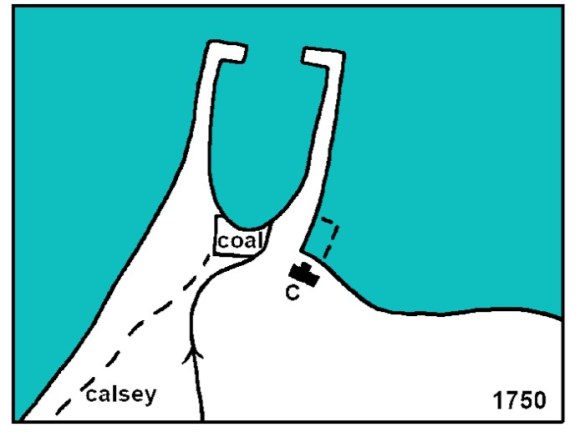

The amount of coal leaving Bo’ness for sea sale was sufficient to warrant the construction of a well-engineered road, a “coal calsey,” from the coal pits to the West Partings, from where the carts had to use the North High Road to the harbour. It utilised part of an old causeway, except where it ran through the parish graveyard, and was completed in 1704. At that time the pier would have been in the area now occupied by the bus station and so the use of the highway was minimal.

The harbour infrastructure was also minimal. There must have been a coal fauld there in order to store the coal prior to the arrival of a vessel for loading. Repair and maintenance facilities developed over time, but it appears to have been the mid-18th century before shipbuilding took place. In January 1705 Alexander Glassford and John Hodge, skippers, expressed a desire to buy Dutch vessels, but this was not considered proper because the Dutch would not buy Scottish salt (Lennoxlove Archive). Five years later Alexander Glassford wrote to the secretary to the Duke of Hamilton describing the port’s need for new ships, and inquiring about a rumoured act of parliament allowing the purchase of ships from Holland. He hoped that the Duke would support such an act, as he wanted a ship for himself, one for James Aire, and one for his father (Hamilton Papers).

Carpenters at Bo’ness were certainly capable of repair work and also building small boats. In the year 1707 the Earl of Linlithgow had a boat built there for his own use. The account was as follows:

“Accompt dew to John Taylor, carpenter in Bor ness, for ane boat built him, to ye use of the Earle of Linlithgow

Impr. To workmanship in building her 20 00 00 Ip to sawing two daills and trees 00 16 00 Ip. For iron work to her and the ruther 04 01 00 It 4 pints and 1 chapin of tar 01 11 06 It 4 punds of Rosenin 00 12 00 It 5 daills and 1 single tree 03 19 00 It for 4 oars 02 00 00 It for 3 single trees to make a slyp qron to

draw her up01 10 00 t to … wt ye men yt wes at heping her on the slyps

at Bor ness, and Linlithgow yr they had don01 09 00 “At Linlithgow the 26th of Jullij 1707, I John Tailyor, carpenter in Boroustoness, grants me to have received from Sebastian Henderson, writer in Linlithgow, the above soum of fourtie six pounds, three shillings, two penies scots, in name of the sd Erle for the sd boat furnished to his use, which is hereby discharged by me, written and subsoyned boath fords by me. JOHN TAILYOR”

(Falkirk Herald 7 August 1851, 3).

Duchess Anne and the Duke of Hamilton had been the patrons of the town for many years, helping to obtain official status for the town and harbour. Early in 1707, amidst the upheaval of the Union of the Kingdoms, their son managed to obtain an Act allowing the town’s officials to raise a tax of two pence on every pint of ale sold in the burgh. This was vital for investing in the harbour upon which so much of the trade depended. It brought in substantial sums of money:

“Charge of the two pennys on the pynt of ale, collected by Andrew Watson:

1708 1803.19.06 1709 1724.03.06 Total 3528.03.00 salary for collection, @ £200 Sterling per year 400.00.00 salary for Anthony Wallace, a crown a week 312.00.00 Total 792.00.00 Leaving 2736.03.00 Whereas Provost Glen offers 3,000 merks per year, for 2 yrs 4000.00.00 Which would be a gain of 1263.17.00 (Lennoxlove Archives)

Provost Glen of Linlithgow also proposed advancing £300 at the signing of the tack “for the more effectual building of ye pier, he getting allowance of it in his tack deuty.”

At the same time Bo’ness appears to have become independent of the customs house at Blackness. More building took place. The Vennel to the west of Dymock’s Building eventually became Scotland’s Close and opposite that building was a house built in 1711 – the inscription “17 MG MR 11” appearing on the door lintel. It became the West Pier Tavern, serving the sailors coming off the ships (now Bo’ness Library).

It was with the intention of determining the suitability of Bo’ness for a naval shipyard that the famous Scottish surveyor John Adair visited in 1709, 1711 and 1712. On the first occasion he went to look at Alloa and on his way back

“did stay at Borroustounes and is of opinion it will be the most proper place for frigats and lesser ships, but not for large men of war. He is lykeways of opinion yt a most admirable harbour might be maid there.”

He kept in touch with the authorities at Bo’ness and 1711 saw him advising the Harbour Trustees to accept William Glen’s offer to collect the 2d tax. He and Mr MacGill were then consulted about how that tax was to be spent upon improvements at Bo’ness Harbour:

“Mr Adair thinks a thousand pound sterling would finish the westmost head of yt peir which is what is most requisite”

(Hamilton Papers).

He was still working on the plans for the naval dockyard in 1712 and discussed with the harbour authorities

“very fully about the town of Borroustounes and harbour in reference to the Docks. And he is of opinion their will be no need for a wett dock and the fery is the only proper place for the dry dock, for he proposes all the ships should in the winter time in place of a wett dock anchor betwixt Blacknes and Borrowstounes which is the best and most commodious wet dock in Britain. And he proposes that all the store houses should be at Borroustounes for he proposes nothing att the ferry but only a dry dock for cleaning the ships… And all this project he proposes will be no very great expense, ffor he is positive nothing can ever be done to purpose at Leith” .

(ibid)

The development of the town of Bo’ness during the 17th century had been little short of amazing. Robert Sibbald was astonished and this is clearly shown in his account of the shire published in 1710:

“In the last Centurie, this part of the Coast has encreased much in People, for now from the Palace of Kineil, for some two Miles, are almost continued buildings upon the Coast, and above it upon the sloping ground… It is perhaps one of the best instances of the advantages of Trade can be seen in this Countrie, the flourishing of this place… I knew in my time, that they and the south Ferrie had some 36 Ships belonging to them, tho in al that tract upon the South side of the Firth, there is no part for Ships to lye at, but at Blackness. There were many rich men Merchants and Masters of Ships liveing there, and the Cities of Glasco, Stirling, and Linlithgow had a great Trade from thence, with Holland, Bremen, Hamburgh, Queensburgh and Dantzik, and furnished all the West Country with goods they Imported from these places, and were loaded outwards with the Product of our own Countrey.”

(Sibbald 1710).

The Union of the Kingdoms introduced a change in the Customs collection and the imposition of the English system. Under this Bo’ness retained a Custom House with an allotted district. This decision was not without its problems and in August 1707 the head office in Edinburgh wrote to the Duke of Hamilton:

“We presume to acquaint your Grace that Sr Harry Rollo having done us the favour to come unto our Board, we discours’d him about Burroustoness, and its districts, and it troubled us to understand that the comon people had been riotous to the Queens Officers.

“We presume to acquaint your Grace that Sr Harry Rollo having done us the favour to come unto our Board, we discours’d him about Burroustoness, and its districts, and it troubled us to understand that the comon people had been riotous to the Queens Officers. We are sensible, My Lord, that all beginnings are difficult. We are likewise made sensible that your Grace hath discourag’d such doings, which makes us the bolder in praying your Grace for to continue such your kindness to the Queen’s servants...”

(Hamilton Papers).

The new arrangement could have its advantages as John Hamilton, the factor for Kinneil Estate pointed out to the Duke of Hamilton on 10 April 1711:

“I think your Grace may gett some part for building the harbour of Borroustouness is this – that since ye union all prohibite goods and all ceasures that are maid are publickly sold and exposed in Exchequer, the on halfe whereof belongs to the seasour maker and the other half to the Queen which is entearely att her disposall and is no ways a pairt of the Customes. Now I am told their will be about seven or eight thousand pounds now in Exchequer belonging to the Queen. So I dont doubt but if your Grace make application for a pairt of this for so necessary a work, it wont be refused…”

(Hamilton Papers).

At the same time Walter Cornwall had written to the Duke of Hamilton complaining that his son had been turned out of the place in the customs at Bo’ness secured for him , and asking that if Mr Balgounie was promoted his place at Bo’ness be given to his son. The patronage of the aristocracy was very important.

| Walter Cornwall | c1700 | Mr Balgounie | -1711 |

| John Burns | 1780s | Sir Henry Seton | -1788 |

| Alexander McNeil | 1788- | John Dunlop | -1801 |

| Archibald Stewart | 1801- | Robert Middleton | |

| Robert Agnew Esq of Sheuchan | -1817 | William Sharp | 1818- |

| James Haig Cobham | c1840 | John C Sheenhan | -1847 |

| John Lewthwaite | -1850 |

The old pier had badly decayed and the Commissioners of Customs threatened to remove the Custom House from Bo’ness if it was not improved as people were landing goods elsewhere, making it difficult to police. It was therefore agreed that Provost Glen would lend the money for the project and would be paid back from the 2d per pint. The work had to be completed the same year that it was started, otherwise the winter storms would undo much of it. Preparations began in 1712 and terms were agreed with the quarriers. James Crawford was ordered to provide an additional work horse and two carts to carry the stones to the pier with the Kinneil tenants helping as part of their feudal obligations.

Sir John Shaw, who had built the imposing harbour at Greenock, was to provide details for the design. The workmen who had done a pier for Lord Wemyss were invited to quote and Mr Buchanan, mason in Kilsyth, offered to build the pier at half a crown the ell height breadth and length, if all materials were laid at the pier. It was the spring of 1713 before sufficient stone was amassed from several quarries and building work could begin. The larger stone came from the quarry on the south-west side of Castle Lyon. However, Duchess Anne’s son was killed in November 1712 and business matters suffered. In 1715 the town of Borrowstounness sent a representation to her Grace to convey its concerns over the delays in the construction of the harbour. The work was evidently done for we hear no more about the harbour until 1743. The next sasine for Dymock’s Building in 1794 refers to “the hills called the Leasing Hills by the head of the west pier” on the north.

The impact of the Union of the Kingdoms was of particular interest to Daniel Defoe who made a tour of Scotland in 1716 – he is sometimes identified as an English spy. Writing of Bo’ness he says:

“a long town, of one street, and no more, extended along the shore, close to the water. It has been, and still is, a town of the greatest trade to Holland and France, before the Union, of any in Scotland, except Edinburgh; and, for shipping, it has more ships belong to it than to Edinburgh and Leith put together; yet their trade is declined of late by the Dutch trade, being carried on so much by way of England.”

Around 1733 a long pier was added 250 feet to the east of the first one to create a semi-enclosed harbour. Initially the new pier, which also provided additional wharfage, was about 386ft long and gave the complex the classic shape that was to endure for another 150 years or so (Graham 1971, 218).

The 2d tax on ale had been collected for at least 25 years, but as it was intended to be for the one-off purpose of improving the harbour, and that had been executed, it is highly probable that it lapsed. By 1743 the harbour was again said to be ruinous. It was essential for the future prosperity of the town that it was “effectually repaired and made commodious.” This would require a very considerable sum of money, and the town had no revenues to answer the expense. Late in 1743 the inhabitants therefore humbly craved His Majesty George II to give them authority to again levy the 2d imposition or duty. The request was granted by an Act of Parliament on 8 May 1744. The Act provided for the appointment of Harbour Trustees, who were to be nine shipmasters and six merchants belonging to the town. A number of country gentlemen were appointed as overseers, and met once a year to ensure that the Trustees fulfilled the duties and obligations laid upon them. James Main, James Cassels, William Muir, David Stevenson, George Adam, Duncan Glassford, Thomas Grindlay, James Glassford, and John Drummond, shipmasters; Andrew Cowan, James Todd, Charles Addison, William Shead, John Pearson, and John Walker, merchants, were appointed as the first Trustees with power to raise the money. It was to be spent on “clearing, deepening, rebuilding, repairing, and improving the harbour and piers of Borrowstounness” (Salmon 1913, 277).

Thomas Glassford was appointed collector of the duty at £15 sterling as a “cellary for said office yearly.” Actually getting the brewers to pay up proved extremely difficult and this aspect is covered in Salmon’s excellent history (Salmon 1913). John Henderson, who had looked after the harbour prior to the 1744 Act, was granted a commission from the Trustees to continue in that capacity under them as “shoremaster.” It was agreed by a majority to clean and deepen “for the conveniency of shipping coming into the harbour” the east side of the wester key (quay), and two of the Trustees were appointed to meet with the masons who were last employed in building at the “keys,” and “commune” with them as to the work. In due course these Trustees reported that they had “communed” with the masons of “Lymkills” anent building the pier.

However, before work could begin there was a great upheaval as the Jacobite army with Bonnie Prince Charlie descended from the north in September 1745. Earlier that month, anticipating that the enemy would be halted at Stirling and therefore would search for other means of crossing the Forth, Walter Grossett, the Customs officer in Alloa, removed all of the vessels on the north side of the river and estuary to the “safe” harbours of Bo’ness, Queensferry, Leith and Dunbar. It took almost a fortnight. The townsfolk of Bo’ness were fervently anti-Jacobite in sentiment. It was with some incredulity that Grossett learned that the Jacobite army had crossed the Forth west of Stirling on the 13th and he now had to evacuate Bo’ness, giving priority to those ships with cannon and stores useful to an enemy army. The movement of the Jacobite army was rapid and on the morning of the 15th it took Linlithgow. Bo’ness was now within easy reach and an advance guard was sent that afternoon to secure it and any remaining stores. It marched down the hill from Linlithgow with the pipers playing, startling Grossett, who was still in the harbour overseeing the departure of the few remaining ships. As they entered the town he was on the last vessel as it left. At that time the Custom House was at the east end of the High Street and the Jacobites discovered a large number of sword blades and cutlasses there, part of a shipment from Germany. Not surprisingly, the contraband alcohol was also liberated. Goods impounded by the Customs were sold back to the very smugglers from whom they had been confiscated. The type of material being smuggled at this period included aniseed; cassia; pepper; aqua vitae; brandy; cordial waters; gin; rum; wine; vinegar; butter; chocolate; currants; figs; liquorice; prunes; raisins; sugar; cambric; damasks; handkerchiefs; lace; linen; muslin; silks; china; coal; combs; feathers; gunpowder; paper; pearl ashes; playing cards; soap; starch; train oil; wool; coffee; tea; snuff; and tobacco.

The main Jacobite army continued on to Edinburgh and victory at Prestonpans. It then advanced into England leaving a lacuna behind it. A second Jacobite army was raised in the north, but the area around the Forth returned to Hanoverian hands. Then, in the second week of December, it was learned that the main army was returning from Derby and the area had to prepare itself for the next phase of the campaign.

The efforts of the government in Edinburgh concentrated upon stopping the northern army from uniting with that returning from England up the west coast and once again boats were removed from northern harbours to Bo’ness and Queensferry. George Murray and his Highlanders arrived in Falkirk on 4 January 1746. With the main Government army in Edinburgh, Bo’ness was in a sort of no-man’s land, separated from the enemy by the River Avon. A Jacobite raiding party reached Bo’ness on the 6th and requisitioned goods which were taken back to Falkirk. In the following weeks Bo’ness witnessed the movements of the Hanoverian troops – first advancing to the town, then in headlong retreat from the catastrophic battle at Falkirk, and finally returning to stay. Men from Bo’ness had agreed to operate cannon at the battle, but they never even reached the battlefield. They were obviously sailors accustomed to defending their ships against pirates (Bailey 1996). And then it was all over and slowly the daily life and commercial activities picked up. Gun powder continued to be on sale in Bo’ness – Duncan Aire importing it from London.

It was time to collect the 2d tax so that the harbour improvements could go ahead:

“That the Trustees appointed by Act of Parliament for levying the Two Pennies Scots on the Pint, for repairing of the Harbour of Borrowstounness, do hereby give notice, that the annual income of the said impost duty, is to be exposed to publick roup, upon the 21 day of August next in the House of Mrs Bowies vintner there, where the articles and conditions of roup may be seen…”

(Caledonian Mercury 18 June 1750, 4).

| YEAR | The 2d on a Pint Tax |

|---|---|

| 1744 | Granted for 25 years |

| 1767 | Renewed with amendments |

| 1794 | Renewed for 21 years with enlarged powers, including the right to exact an anchorage duty of a penny-halfpenny per ton on every ship entering the harbour |

| 1816 | 25 year extension with more powers including the right to assess and levy from all occupiers of dwelling-houses, shops, and other buildings within the town a rate or duty not exceeding one shilling in the pound upon the rents of such, and to appoint two or more assessors. |

| 1843 | The Harbour Trustees renamed the “Trustees for the Town and Harbour” and a period of service and a qualification set for election and electors. Two pennies duty dropped. |

The contract for extending the end of the west pier was with John Miller, John Clark, and John Wilson, masons in Lymkills. The progress of the masons in preparing the stones at Limekilns was apparently leisurely, and a letter was despatched to see :

“when they intend to come over and build the said pier, and also to make enquirie concerning boats to bring over the stones” (Salmon 1913, 232).

There appears to have been some difficulty in getting the materials across the Forth, but it was solved by the Trustees purchasing an Arbroath boat for that purpose which was then lying at Bo’ness. It cost £60 sterling and the shoremaster was authorised to let it out whenever it was not needed for carrying the pier stones. After the pier was finished the “ston boat” was exposed to public roup in the house of James Rennie, brewer in Borrowstounness, and it was bought by Charles Addison for £66 10s.

As the industrial Revolution gathered momentum more and more coal was required and Bo’ness picked up the pace. Here are just a few examples that give an idea of the scale of the operation and the sizes of the ships employed:

(1) “That there is wanted immediately, a number, not exceeding 10 ships, from 150 to 300 tons burthen, for carrying of coals from Borrowstounness to London, upon a reasonable freight; and if any ships are engaged to go to England for corn, & c, as to Stockton, Hull, Lynn, Boston, Yarmouth, or any other port upon that coast, they shall have the same encouragement; and when the season comes for any ships going for the east seas, to Copenhagen, Dantzick, Hamburgh, or any other port thereof, or any port of Holland, they may likewise depend upon a reasonable freight, for the carrying of coal or salt to these ports respectively. – And if any merchant or shipmaster chuses to take either coals or salt upon their own account, they may depend upon proper encouragement, and quick dispatch. – Apply to the coal and salt office of George Hoar and Company, at Borrowstounness.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 8 January 1757 3).

(2) “There are wanted, twenty ships to freight to London with coals, at ten shillings for each chalder they shall put out at London, and ten ships to freight with coals to Copenhagen, at seven guineas for each 21 tons they shall deliver there. The masters or owners of such ships may proceed to Borrowstounness as soon as they please, where they shall be loaded with the utmost dispatch. – They may apply by writing to Messrs George Hoar and company, at the coal and salt office of Borrowstounness.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 27 Dec 1757, 3).

(3) “Wanted to freight at Borrowstounness, four ships from 100 to 300 tons, to load coals for Gibraltar, at 26L for each 21 tons they deliver out there; and ten such ships to load coals for Copenhagen, at 7L 7s for each 21 tons delivered there. Masters or owners of such ships to be freighted may apply or direct their letters to Messrs George Hoar and company at Borrowstounness.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 18 March 1758,3).

In 1761 Dr John Roebuck took a lease of the Bo’ness coalfield from the Duke of Hamilton. The contract gave him:

“Power and Liberty of using the Pier, Shore, and Harbour of Borrowstounness, in the same Manner, as the said Duke, or his Predecessors, have been in use to do, with any further Privileges relating to the Use of the said Pier, Shore, and Harbour, that may be in the Duke’s Power to grant, and found expedient to be granted, to the said Lessees, and their foresaids, for the more commodious Exportation of the said Coals and Salt, from the Piers and Harbour of Borrowstounness; with Power also to the said Lessees, during the currency of this Lease, to exercise all the Powers and Privileges competent to the said Duke, with regard to regulating the Shore-dues, and Anchorages, Tail-mails, and Dock-mails exigible, or to be extracted from Ships and Vessels, at the said Harbour of Borrowstounness; and with Power to them of appointing the Shoremasters for collecting the foresaid Dues,and regulating the Births of Ships, with the other Powers usually given to Shoremasters; which Dues so to be levied, are to be applied for the Reparation or Improvement of the Harbour of Borrowstounness…”

(Lennoxlove Archive)

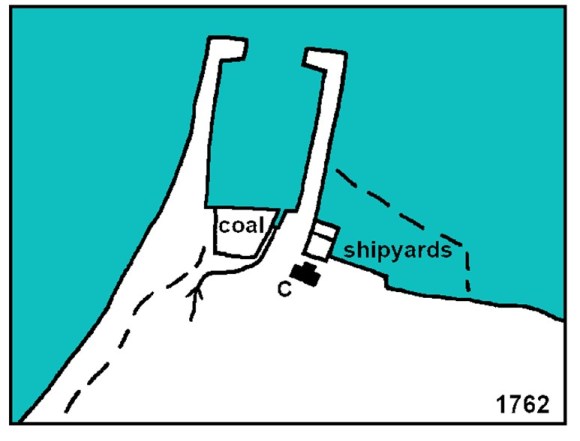

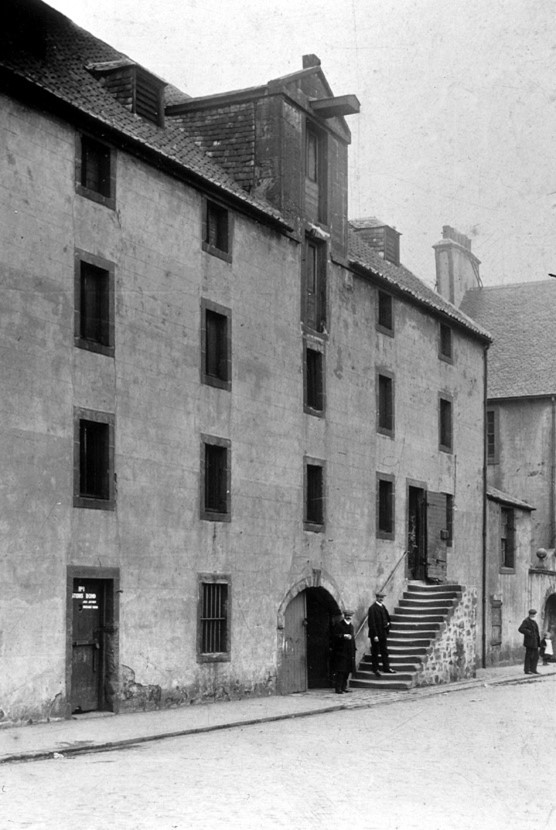

He upscaled coal production and needed to increase the efficiency of his operations in transporting it. Immediately he extended the existing coal fauld at the harbour which required a “bulwark.” This suggests that it was on land reclaimed from the Forth. Action had to be taken to stop John and Robert Cowan, two of the leading merchants in the town, from stacking timber against it and obstructing access to the harbour (Lennoxlove Archive). The extension appears to have interfered with the existing harbour and this brought Roebuck into conflict with the Harbour Trustees. Despite threats to interdict him the work was completed (Salmon 1913, 233). Charles Addison, another important merchant, had been reclaiming land immediately to the east of the harbour. His feu charter of the ground was granted by James, sixth Duke of Hamilton, on the 20 September 1752. The narrative runs –

“Whereas Charles Addison, merchant in my burgh of Borrowstounness, hath already expended a considerable sum of his own proper money in gaining the area aftermentioned from off the sea (upon which there were never any house or houses built, and which never yielded any rent or profite to me or my predecessors), and in building a strong buttress or bullwork of hewen aceler [ashlar] fenced with many huge stones for the support thereof, and will be farder at a very great expence in building a dwelling-house, office houses, cellors, proper warehouses, and granaries on the said area or shoar of the said Burgh, which, works were undertaken and are carrying on by him upon the assurance of his obtaining from me a grant of the said area; Therefor and for his encouragement to compleat so laudable ane undertaking which tends to the advancement of the policy and trade of the said town,”

and in consideration of his paying a yearly feu-duty and on several other terms and conditions, the reclaimed ground referred to was granted him. The boundaries of the ground so feued were given as the sea on the north; the houses of Mary Wilson on the east; the High Street on the south; and the easter pier and highway leading to the same on the west (Salmon 1913, 250).

Having constructed these substantial buildings Addison then put them up for rent:

“That there is a commodious brewery, with cellars, granaries, malt kilns, barns, and a dwelling house, all inclosed in a court, and built in the best and most useful way within these five years, lying at the east end of the town of Borrowstounness, to be either sold, set in tack, or carried on in a company concern by the proprietor, and any sufficient man that may offer to engage in that way; to be entered to the end of January first. For any of the above proposals, apply to Charles Addison merchants in Borrowstounness.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 6 November 1762, 4).

The large house on the south of this complex fronted North High Street and the ground floor was let out for shops, the first floor became flats, and the second was devoted to the Custom house. The building then took the name of “Regent House.” 1767 saw yet another Act of Parliament for Bo’ness, which empowered the Harbour Trustees to appoint a harbourmaster and to extend the beer tax already in force. Since the 1688 sasine for Dymock’s Building the northern High Street, which had only led to the west pier, was diverted and extended across the waste ground to the east. Beyond the waste ground was an open area which had been used for the storage and handling of cargoes in relation to the “shore” to the east of the old harbour. As this public space became more and more cut off from the shore as a result of progressive land reclamation and building, it was turned into a new market square.

Roebuck continued with his improvements to the transport infrastructure for his coal and needed the help and agreement of the Harbour Trustees. On 14 September 1762 he wrote to them:

“Gentlemen, – Being extremely willing to cultivate and maintain a good correspondence with the inhabitants of Bo’ness, and as far as in my power to promote their interest and accommodation, I take this opportunity to communicate to such of your members, whom I had not the pleasure of seeing at my house on Saturday, that I propose to carry down a waggon road on the west side of the west key and on the east side of the east key for the greater dispatch of vessels coming here to load coals and salt. As in the execution of my design it may be necessary to remove some of the polls on the key for my own accommodation and for the convenience of carts passing up and down the key with merchants’ goods, I propose to erect new ones in place of those removed and to plant iron rings by the side of the key in such manner as shall not endanger the key and at the same time secure ships moored thereto. And for the more speedy shipping of coal, and to prevent the same from being a nuisance to the pier, I propose to erect two cranes, but in such a manner as shall be no injury to the pier or inconvenience to the merchants or shipmasters, but occasionally may be used for their benefit.

Being much concerned for the present state of the harbour, which in a little time must injure, if not ruin, the trade of the town, and understanding from the gentlemen with me on Saturday that the public funds of the town are such as will not allow instantly to remedy the growing evil, I offered to them to advance in the name of the company any sum not exceeding four hundred pounds, free of interest, for executing this laudable and desirable purpose, desiring only to be repaid by receipt of the harbour’s revenue after payment of the present debts due thereon, which proposal or promise I still adhere to and oblige myself to perform in case you signify your concurrence therewith.

I hope, gentlemen, you will consider what I have said as flowing solely from a desire to live in peace and harmony with the gentlemen of Bo’ness, and to contribute as much as in my power to the prosperity of the trade of the town.

If the whole proposals are agreeable to you I shall be obliged to you if you will enter them in your sederunt book; and, if not, that you would favour me with your answer. — I am, gentlemen, your most humble servant, (signed) John Roebuck, for self, and coal company.”

(Salmon 1913, 236).

All the proposals were agreed to by the Trustees and six days later the Doctor was made a fellow Trustee.

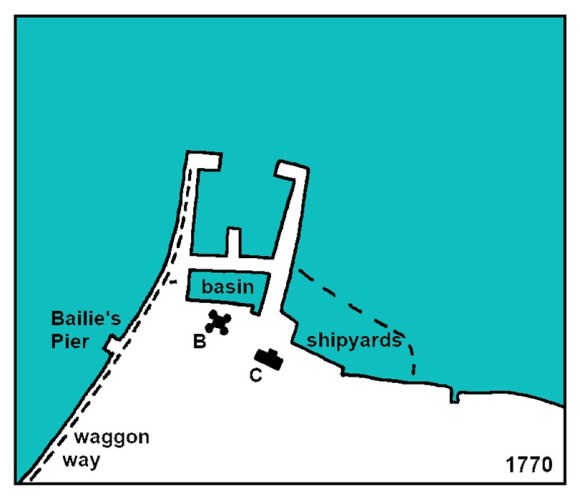

Between 1750 and 1780 Borrowstounness was one of the most thriving towns on the east coast, and ranked as the third port in Scotland. The Trustees were constantly engaged in making improvements at the harbour for traders. The continuous deposition of mud silt gave great trouble and so in August 1760 the following advertisement appeared in the newspapers:

“That the Trustees appointed by act of parliament for building and repairing the harbour of Borrowstounness, are to build a basin for cleaning the said harbour, they desire that any persons willing to undertake the building of the said basin may give in their proposals to the trustees at Borrowstounness… enquire Mr Walkinshaw or any other of the trustees at Borrowstounness.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant20 August 1760,4).

Things moved slowly and a similar notice was printed in October 1762. This time the work went on apace and was finished by May 1764. The Trustees were highly satisfied with the result:

“By order of the Trustees, appointed by act of parliament for managing the harbour of Borrowstounness.

THAT the harbour of Borrowstounness being greatly choaked up with mud and clay, and daily growing worse, so as in few years to become intirely useless and inaccessible for vessels of the smallest burthen, having only from six to seven feet water in neep-tides. To remove this growing evil, threatening the ruin of the trade, and navigation of the place, the Trustees, after trying several ways in vain, did last year resolve on erecting a bason or reservatory of water, as the only means to effectually wash away the great body of accumulated clay and mud in said harbour. –

They accordingly contracted with Robert M’Kell, Engineer at Falkirk, to build a bason, with four large sluices, to open and shut easily by one man with tooth and pinion, and to be otherwise finished in a proper manner, agreeable to a plan fixed upon. This bason was accordingly built by Mr M’Kell, and finished last November, – And The Trustees do now with much satisfaction inform the public, that the good effects of this bason even exceeds expectation; and has already, in few months, thoroughly cleaned and deepened one side of the harbour, where there’s now water to receive vessels from 300 to 500 tons; and in like manner, they hope it will soon clean and deepen the whole harbour. And this information they thought necessary to make to all trading to this port, particularly to those for coal and salt.

The Trustees being likeways extremely sensible of Mr M’Kell’s ability, diligence and activity, in executing this bason, think they would be wanting in justice to his merit and genius, if they did not take this occasion of recommending him as a person worthy of encouragement, and every way fit for executing work of this kind, and also for many other mechanical operations. And appoint this intimation to be insert n the Edinburgh Courant and mercury.

Signed by order of the Trustees,

James Scrimgeour, junior.”

(Caledonian Mercury 30 May 1764, 1)

The double wall housing the sluices had been run across between the two piers, enclosing the southern one-fourth of the harbour. Robert McKell went on to do the bulk of the engineering work on the Forth and Clyde Canal. The Harbour Trustees were at the height of their powers and were gifted an axe with a silver grip bearing the following inscription: “By Authority of the Trustees of the Harbour of Borrowstounness. Constituted by Act of Parliament. Anno, 1767.” (Falkirk Herald 1 May 1937, 11). This was probably used by the shoremaster as his symbol of authority and recalls the use of an axe at Grangemouth to maintain control (Bailey 2023, 24).

In the 1760s the Greenland whale fishing had been prosecuted with great briskness by some of the enterprising local merchants, and quite a number of whaling ships belonged to the port. When not in Greenland, these vessels lay alongside the piers. With the greatly increased commerce, all the available quay space at the harbour was required for regular traders and so on 21 July 1763 the Trustees declared:

“That the Greenland ships cannot be laid by the sides of the piers during the interval of fishing without great prejudice to the trade of the town by stopping the loading and unloading of other vessels, therefore the trustees have resolved that they shall lie only in the middle of the harbour at equal distances from each pier, and do order John Kidd, havenmaster, to be served with a copy of this their resolution.”

Charles Addison, one of the Trustees, and a member of the firm of Charles Addison & Sons, merchants and brewers, owned a Greenland ship called the Peggy, which, in September 1764 was reported as

“lying in the best part of the harbor which greatly interrupts the loading and unloading of other trading vessels through the winter.”

The shoremaster was instructed to tell Addison to move her into the middle of the harbour “where she was in use to lie in former years.” Eventually Addison agreed to remove the vessel alongside the Oswald, but only after the Trustees had employed labourers to “throw a ditch” to let her up. It would seem that the centre of the harbour still suffered from silting (Salmon 1913, 240-1). As well as the Peggy and the Oswald, Bo’ness was also home to the King’s Fisher, Borrowstounness, Glasgow Fisher and the Leviathan.

The Town House was built in 1776 at the head of the harbour by the Duke of Hamilton, occupying the area formerly taken by the coal fauld (with the installation of the basin it was no longer as convenient for that purpose). The ground floor was for use as a prison, the second floor for a court room, and the attic storey for a school. It was based upon the design of Inverary House and was intended to be imposing (Rennie 1796). Its northern foundations sat on the old quay wall, which now formed the southern wall of the reservoir basin and this gave it extra gravitas from the seaward side. The Town House was later used by the Town and Harbour Trustees to hold their meetings.

In June 1767 the Bo’ness Harbour Trustees proposed to build a tongue or short middle pier and arranged for bids for the work. It was centrally placed on the cross wall that formed the reservoir basin. Additions were afterwards made to the tongue and the piers from time to time as necessity arose. It was minuted that on one occasion during the many repairs to the piers that the masons “are very slothfull in performing their day’s work.” The shoremaster was therefore instructed

“to oversee said masons two or three times a day, and if any of them be found idle or neglecting their work to take a note of their names and to report them to the trustees as often as they shall be found that way.” At a later date we find the same strict supervision over the same kind of work – “It is agreed that Daniel Drummond, the harbourman, shall work as a labourer with the masons, where he shall be directed during the whole repairs. And if it shall be found that he attends and works faithfully, and takes care to make complaint when the other workmen do not their duty, the trustees mean to make him some little present when the work is finished.”

(Salmon 1913, 247).

In 1769 the streets of the town were repaired and £6 was spent on the east pier, and £6 to pave the west pier down to the basin wall.

It is around this time that shipbuilding seems to have been conducted on the open shore to the east of the eastern pier.

| YEAR | SHIP’S NAME | BUILDER | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1761 | Campbell | James Main, master | |

| 1761 | Roebuck | Duncan Aire, master | |

| c1762 | Lovely Peggy | Brigantine of 70 tons burden | (sold 1764) |

| 1763 | Mary & Jannet | Sloop of 60 tons | |

| 1764 | John & James | Sloop of 90 tons | |

| 1764 | Richmond | 240 tons | |

| 1766 | Antelope | Brig of 114 tons | |

| 1769 | Lochnell | Sloop of 47 tons | James Smart for D & A Angus of Greenock |

| 1778 | Mercury | 75 tons | |

| 1779 | Argo | Sloop of 42 tons | Robert Smart |

| 1780 | Atlantic | 450 tons burden | George Hart for Capt Alexander Chystie |

| 1783 | Betty & Molly | Brigantine of 87 tons | George Hart for McAusland & Co |

| 1784 | Forth | Brigantine of 120 tons | |

| 1785 | Josiah | Sloop of 75 tons | |

| 1786 | Phemie | George Hart for A & J Robertson & Co | |

| 1786 | Cochrane | Sloop of 55 tons | George Hart for Robert Boag & Co |

| 1786 | Jean | Brigantine of 91 tons | |

| 1787 | Stewart | Sloop of 72 tons | George Hart for Robert Boag & Co |

| 1787 | Mary | Brigantine of 165 tons | George Hart for Robert Boag & Co |

| 1788 | Diamond | Sloop of 65 tons | Robert Smart |

| 1788 | Britannia | 286 tons | George Hart for Hunter, Robertson & Co |

| 1788 | Grizzell | Sloop of 63 tons | George Hart for William Gow of Polmont |

| nd | Jeannie | Sloop of 60 tons | (for sale 1790) |

| nd | Ceres | Sloop of 44 tons | George Hart for John Sword of Leith |

| 1790 | Freedom | Sloop of 56 tons | George Hart for William Gow of Polmont |

| 1792 | Rachell & Catherine | Sloop of 52 tons | Robert Smart |

| nd | Nelly | Sloop of 76 tons | (in use 1796) |

| 1796 | Minerva | Brigantine of 153 tons | |

| nd | Dispatch | Sloop of 42 tons | (for sale 1800) |

Dr Roebuck was declared bankrupt in the early 1770s and the management of his business concerns was put into the hands of trustees. The coal working operations were overseen by John Allenson and John Grieve. The removal of the coal fauld at the harbour made it essential that a scheme to construct a waggonway along the route of the old coal calsey be revived. In 1772 the Harbour Trustees consented to the construction of the waggonway upon certain important terms and conditions. One of these was that a new street be formed from the bottom of the Kirk Wynd to the harbour, thus avoiding the main road. This was placed along the coastline, requiring the use of an embankment – today it is appropriately known as “Waggon Road.” The paving of the new street was to be done with Queensferry stones “by proper bred pavers.” To ease the contour at the foot of the Kirk Wynd the waggonway crossed the shore road to Falkirk on a 3ft high bank, making the use of that road somewhat inconvenient. The Harbour Trustees thought that it would end at the head of the west pier and were considerably disturbed to find the work extended along the pier. This might prove prejudicial to the trade of the town “by making it impossible for carts carrying down and up goods from passing each other.” But a workable solution was put in place. It was then discovered that each waggon “is to carry about three tons of coal, which is about or near to double the weight that Dr. Roebuck’s waggons formerly carried.” However, Allensen and Grieve bound the colliery to make good any damage that might be done to the pier by the waggonway. The harbour authorities viewed the scheme as essential as

“the success of the coalliery of this town is perfectly connected with the trade and prosperity thereof”

(Salmon 1913, 249).

From the beginning of its use as a port there had been problems at Bo’ness with ships throwing their ballast overboard as they entered the port, creating obstacles to navigation. Several Acts of the Scottish Parliament had forbidden such practices, but they continued. James Baird, the shoremaster, reported on 8 March 1773 that Charles Baad, master of the sloop Venus, had entered the harbour and had later thrown ballast out. Baad denied that he brought in any ballast, upon which the Trustees called in John Thomson, workman, and put him on oath. He deponed that he had been sent on board to get “a parcell of wands” for Dr Roebuck & Co’s coalworks, and that he saw over twenty carts of ballast. After he had removed the wands Baad engaged him to go back about eight o’clock at night, when it was dark, to assist to throw out the ballast. The sloop had been hauled off about a cable length north of the west pier, and Baad took him to it in his small boat. When he got aboard he found Daniel Robertson, carpenter, and Baad’s own men busy throwing the ballast overboard. He then commenced to help, and it was all out in about an hour. Daniel Robertson corroborated this account. Baad was fined £10 and if he failed to pay the sloop was to be distressed “by carrying off as many of her sails as when sold will amount to the sum of ten pounds, with all charges of every kind.” The Trustees had some difficulty in getting the fine, but after taking possession of the sails the money was paid (ibid, 252).

Towards the end of 1780 Dr Roebuck’s trustees composed an interesting and curious memorandum relating to the coal works. Amongst other proposals is this one:

“The trade of Borness has been on the decline for several years past and its thought by many sensible people that it cannot be recovered without the assistance of a dry dock. If this dock were built, its without doubt that it would be of a considerable advantage to the sale of coals and otherwise very beneficial to the town. This dock is supposed to take £1,000 which is to be divided into twenty shares of £50 st, of which Dr Roebuck proposes to take five shares, and he and the inhabitants wish not only that His Grace would take a share, but also that he would allow the dock to be erected on the west side of the basin at the harbour of Borness...”

(Hamilton Papers).

The purpose of the dry dock given in this statement is such that it suggests that it was to be used as a wet dock for loading colliers when not in use as a dry dock for repairing ships. The Harbour Trustees saw “of what great utility the having a dry dock properly executed in the bason would be to the trade and commerce of this town” and asked Dr Roebuck and Mr Cowan to procure plans and estimates (Salmon 1913, 259). The proposal never went ahead.

Constant warfare with Spain, France and Holland took its toll on the men and ships of Bo’ness. In 1761, for example, the Patience of Bo’ness was captured by a privateer and ransomed for 280 guineas; and the following year the Janet for 205 guineas. Convoys escorted by the Royal Navy were one answer. Financial support for the Navy came from the merchants of Bo’ness:

“Borrowstounness Bounty, for seamen and landmen to his Majesty’s ship Grampus under the command of Lord Cranstoun. Some gentlemen in Bo’ness have agreed to give the following bounty, over and above the like bounty given by the Countess of Hopetoun, and all other bounties in the county of Linlithgow.

Thirty shillings for every able seaman. Twenty shillings for every ordinary seaman, and ten shillings for every able landman. To be paid when the King’s and Countess of Hopetoun’s bounties are certified to be paid, on applying to Mr John Cowan, Baillie of Bo’ness. NB The Grampus is now shipbuilding at Liverpool, to be launched in a few days.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 14 Sep 1782, 3).

| SHIP’S NAME | YEAR | MASTER | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hopeton | 1754-61 | Duncan Aire/ Robert Craig * | |

| King’s Fisher | 1754 | Whaling ship | |

| Neptune | 1754-62 | Charles Addison/ Richard Grindlay * | 120 tons (for sale 1754) |

| Glasgow & Paisley Packet | 1754-64 | John Thomson/ Richard Gardiner * | |

| Prince of Orange | 1754-58 | John Falconer * | |

| William & Mary | 1754 | John Drummond | |

| Argyle | 1757 | Alexander Mitchell * | New in 1757 |

| Charles | 1757 | Glassford | |

| Dolphin | 1757-67 | James Main/ Richard Hardie/ Robert Brown * | Brigantine of 140 tons, 2 guns |

| Fortune | 1757-8 | Duncan Pollock | Snow of 150 tons |

| Glasgow Packet | 1757 | Andrew Cassels * | |

| Neptune | 1757-63 | Richard Grindlay | |

| St Andrew | 1757 | William Marshall * | |

| Borrowstounness | 1758 | Whaling ship lost | |

| Eagle | 1758 | James Forbes | |

| Friendship | 1758-67 | James Hamilton/ Hercules Angus/ James Cowan | |

| Glasgow Fisher | 1758 | Whaling ship | |

| Industry | 1758 | William Moor | 200 tons mounting 6 guns |

| Isabell | 1758-62 | ||

| John | 1758-63 | Richard Cram/ Richard Bryce | 120 tons, built in Hull |

| Oswald | 1758-67 | Hodge | Whaling ship |

| Reward | 1758 | William Marchall * | |

| Campbell | 1760-64 | James Main * | |

| Diligence | 1760-85 | Andrew Cassels/ Comb * | |

| Elizabeth | 1760-62 | Gray/ James Arbuthnot/ William Brown * | |

| Patience | 1760-67 | James Grindlay * | Ransomed for 280 guineas 1761 |

| Peggy | 1760-67 | Whaling ship | |

| Samuel & Jean | 1760-67 | James Drummond/ John Drummond * | |

| Betsy | 1761-62 | Andrew Aire * | |

| Busy Bee | 1761 | Duncan | |

| Diana | 1761 | George Ritchie | New in 1761 |

| Dispatch | 1761-80 | John Hardie/ Henry | |

| Pythagoras | 1761-62 | Sime | |

| Reward | 1761-62 | William Marshall | |

| Roebuck | 1761-62 | Duncan Aire/ John Forbes | Built 1761 |

| Thomas & Ann | 1761-62 | Achie/ Brown | |

| Elizabeth | 1762 | William Hodge/ Marshall * | New in 1762 |

| Grizzel | 1762 | James Hunter | Built in Montrose c1750 |

| Janet | 1762 | Alexander Jamieson | Ransomed for 205 guineas 1762 |

| Lovely Mary | 1762 | Duncan Stirling | New in 1762 |

| Anne | 1764-67 | Richard Paterson | |

| Earl of Bute | 1764 | William Marshall * | |

| Fortune | 1764 | Richard Bryce | |

| John & Peggy | 1764 | ||

| Lovely Peggy | 1764 | Nimmo | Brigantine of 70 tons |

| Thames | 1764-80 | Richard Grindlay * | New in 1764 |

| Duchess of Hamilton | 1767-85 | James & John Forbes, John Hay, James Main/ Kay * | |

| Duke of Athol | 1767-85 | Miller/ Hart | |

| Duke of Hamilton | 1767 | Andrew Stone | |

| Elizabeth & Jean | 1767 | Robert Halket | |

| James | 1767 | Capie | |

| Lilly | 1767 | Hercules Angus | New in 1767 |

| Lovely Janie | 1767 | John Lamb | Brig |

| Marie | 1767 | James Gindlay * | New in 1767 |

| Nancy | 1767 | Rea | |

| Peggy | 1767-85 | Rae/ Melvin. O Connacher | |

| Providence | 1767 | ||

| Mary | 1767-80 | Blair/ Martin | |

| Speedwell | 1767 | Johnston | |

| Two Brothers | 1767 | Ridley | |

| Allan | 1780 | Turnbull | |

| Betsy & Peggy | 1780 | Robertson | |

| Fair Elliot | 1780 | James Mackie | New in 1780 |

| Glasgow | 1780 | Shaw | |

| Mercury | 1780 | Kincaid | Built 1778 |

| Robert | 1780 | Keay | |

| Unity | 1780 | James Grindlay | |

| William | 1780 | Paterson | |

| Cecilia | 1784-85 | Johnston/ Grindlay | |

| Christian | 1784 | Cocker | |

| Countess of Hopeton | 1784 | Main | |

| Endeavour | 1784 | Clark | |

| Four Brothers | 1784 | Long | |

| Four Sisters | 1784 | Kay | |

| Good Intent | 1784 | Sloop of 75 tons | |

| Jean | 1784 | Robert Grindlay | Wrecked December 1784 |

| Maria (Marion) | 1784-75 | Henry/ Westwick | |

| Prussian Hero | 1784 | Kay | |

| Robert | 1784 | Kay | |

| Three Friends | 1784 | Scott | |

| Unity | 1784-85 | James Grindlay. O Connacher | |

| Sir Laurence | 1784-85 | Halket | |

| Fanny | 1785 | Black | |

| Janet & Margaret | 1785 | For sale 1785 | |

| Jeffry (Jessy) | 1785 | Berry | |

| John | 1785 | Clerk | |

| Leviathan | 1785 | Pottinger | Whaling ship |

| Marine | 1785 | Henry | |

| Memphis | 1785 | Gardiner | |

| Ruby | 1785 | Johnston |

*contract ship 1757-1767, providing a joint service to London.

Planning for the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal was well underway before Robert McKell had completed the reservoir basin at Bo’ness and the merchants there were concerned about where its eastern terminus was to be located, lest it take trade away from them. McKell therefore produced a short report in 1765 showing that an extension of that canal from near the mouth of the River Carron to Bo’ness was viable. Consequently representatives of Bo’ness put in a strong appearance at Westminster in 1767 during the passage of the proceedings that led to the Act of Parliament for the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal. John Forbes was a local skipper and he informed the panel that Bo’ness Harbour was capable of taking twenty ships of up to 500 tons burden. The tides there rose 17ft at Spring Tides and 11ft at Neap Tides, meaning that ships could enter the harbour at any time, especially as it was unaffected by land floods or frost. By contrast, at Carronshore Spring Tides rose 8 or 9ft, and at Neap Tides 5 or 6ft. Vessels of as little as 30 or 40 tons, drawing only 5 or 6ft of water, could not go up the River Carron at Neap Tides. In moderate weather, if the wind was contrary, the vessels might have to wait three or four tides, and this would be exacerbated if the river was straightened. However, with a fair wind and tide the voyage could be accomplished in as little as four to six hours. It was not unknown, he stated, for vessels to be detained four or five days, and in frosts up to three weeks. Floods on the land adjacent to the River Carron made navigation along it hazardous in the winter. On 8 March 1768 royal assent was given to an Act for the construction of the Forth and Clyde Canal and

“for making a navigable Cut or Canal of Communication from the Port or Harbour of Borrowstounness, to join the said Canal at or near the place where it will fall into the River Carron or Firth of Forth.”

Subscriptions were raised and a large amount of the locally available capital was sunk into the project – the stakes were high. Construction work on the Bo’ness Canal began in 1783. Over £7,500 was spent but by 1790 it was apparent that it would take more than that amount to complete it and the scheme had to be abandoned leaving many in Bo’ness the poorer to no advantage for the town (see The Bo’ness Canal Navigation).

In January 1785 the Harbour Trustees advertised for estimates to add 30yds to the Eastern Pier of Borrowstounness. A further advert appeared a year later with more details:

“Mason Contractors Wanted. The Trustees for managing the harbour funds of Borrowstounness propose, without delay, to build 30 or 40 yards to the end of the East Quay, with stones of the following dimensions, viz length of the stones: one half from 4 to 5 feet, and the other half not less than 3 feet. Thickness from 12 to 18 inches, medium 15 inches, and breadth from 15 to 22 inches, medium 18.5 inches. The thickness of the wall on each side of the quay six feet at bottom and four feet at top. It is proposed to hearten with fletch one yard thick on the inside of the walls, to be taken out of the harbour, and the rest of the heartening taken from the basin and ballast hill, it being understood that the contractor engage to do everything, and the Trustees to do and furnish nothing, they only engaging to make regular payment to the Contractor as shall be agreed on…” David Milne officer of excise & James Baird harbour master.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 3 April 1876,4)

The construction work was underway in September 1787 when the Trustees made the following announcement:

“Shipmasters and pilots are informed that an addition of 45 yards is now building to the end of the East Pier of the harbour of Borrowstounness, and that sloop loadings of large stones are from time to time laid down within the limits of this extension. That damage to shipping while this work is going on, may be prevented, the Trustees for the harbour have caused a beacon to be erected, without or to the north of which vessels may take the harbour clear of the stones.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 22 September 1787, 4).

The beacon was only partially successful and the Trustees blamed negligent shipmasters and pilots:

“The Trustees for the Harbour find that this beacon has frequently been driven down, by vessels coming upon it, or ropes being made fast to it. Aware that the want of such a guide, even for a single tide, may occasion great loss of property, the Trustees think it a duty they owe the public, to caution shipmasters and pilots against damaging the Beacon in any way whatever; and hereby publish their resolution to prosecute with rigour every offender, not only for replacing the Beacon, but for a smart fine; besides that, after this notice, any loss of property, which may be incurred by the temporary want of the Beacon, will most certainly fall on the aggressor.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 10 November 1787).

The extension was not found to be sufficient and the broad mouth between the two piers did not offer enough protection in severe weather. And so the exercise was repeated in 1794:

“To shipmasters. The Trustees for the Harbour of Borrowstounness inform the shipmasters and pilots frequenting that harbour that a beginning has, within these few days, been made to build an addition to the East Pier, extending 160 feet north-west of Old Easthead, and contracting the harbour mouth to 100 feet. To prevent accidents to ships entering the harbour, two beacons are set up, of which all concerned are requested to take notice.

NB. The Trustees having found difficulty in keeping the hazards at all times sufficiently marked by beacons, do, on this account, advertise again to request, that no stranger, or others unacquainted with the state of the new work, venture on taking the harbour without a pilot.”

(Edinburgh Evening Courant 1794, 1).

Quite unexpectedly shoals of herring appeared in the Forth in the 1790s and resulted in a fishing bonanza. So successful was the 1794-5 season that hopes were entertained that herring curing would be added to the industries of Bo’ness. The Trustees thought that the herring vessels which then occupied the piers should be made to pay a small allowance for the use of these, and also to meet the necessary repairs which carts with a great weight of fish would occasion. If “little ordinary trade was going forward,” they admitted, the use of the piers could be permitted with little inconvenience; but “if trade otherwise was brisk,” the herring curing would prove a great obstruction and so the herring vessels should pay a little. This was to be done “so gently as not to make the busses avoid the harbour” as “this being the outset of a new business.” A committee of three was therefore appointed to inquire into the practice and mode of charge in other places where the piers were so used, and to draw up such regulations as appeared to them adequate before the return of the next fishing season. These “Regulations for the curing of herrings at the harbour of Borrowstounness” stated that persons in charge of “busses” (herring vessels) on entering the harbour were to state whether they meant to cure any of their fish upon the quays. If so, they were to be charged 4d per ton register for the privilege in addition to the anchorage duty. If no notice was given, and herrings were found on the quays beyond the space of forty-eight hours, they were to be seized and sold, and the proceeds converted to the use of the harbour. If any vessel did not cure to the extent of her full loading, the person in charge, on making testimony of the reason, was to receive a return of such part of the curing dues as the collector thought fit. Those not having vessels, but who might purchase herrings and cure them on the quays, were likewise to pay the dues. Six barrels were to be reckoned as equal to a ton register. Unfortunately, the appearance of the herrings was limited to just a few years (Salmon 1913, 258-9). There was tragedy amongst the bounty:

“Extract of a letter from Boness, Dec 2: “Our herring fishing here comes on well, but unfortunately a violent hurricane came on here and up the Frith on Monday last, which continued all that day, and was the cause of several loaded boats with herrings being lost. One boat particularly was lost within twenty yards of our quay, fully loaded; the men were saved by a boat going out immediately to their assistance, but with the utmost difficulty. There are none of the boats crews belonging to this place that have suffered, so far as we know, though several bodies have this day been picked up on the opposite shore, supposed to belong to Grangemouth, &c. It still blows so hard that no boats have- ventured out to-day. The herrings are selling here at eight-pence per hundred.”

(Saunders’ News Letter 23 December 1795, 1).

The appearance of the herrings is also mentioned by the parish minister in his statistical account of Bo’ness in 1796. Concerning the shipping belonging to the town, he states that there were :

“at present 25 sail; whereof 17 are brigantines, of 70 to 170 tons per register; and 8 sail are sloops, from 20 to 70 tons per register, employing about 170 men and boys. Of the brigantines, 6 are under contract to sail regularly once every 14 days, to and from London. They are all fine vessels, from 147 to 167 tons per register. The remaining 11 brigantines, and 1 of the sloops, also a good vessel, are chiefly engaged in the Baltic trade. The other 7 sloops, are for the canal and coasting. The shipping of the port, including all the creeks, are said to be nearly 10,000 tons per register; and those of Borrowstownness, make about one fourth of the whole.”

(Rennie 1796).

Clay from Devonshire was now amongst the imports, for use at the new pottery established by Dr John Roebuck. The changing nature of the trade was emphasised by Rennie and it is worthwhile repeating his account of it:

“Coal and salt are the principal exports of the place, and the imports are grain, timber, tallow, flax, and flax-seed, with other Baltic and Dutch goods. The exportation of coal to Holland, had become very early a considerable branch of trade here; and Borrowstownness, for the first 50 or 60 years of this century, was a great mart for Dutch goods of all kinds, particularly flax, flax-seed, and old iron. But as the manufactures of this country advanced, so as to increase the demand for Dutch flax, the traders and manufacturers in other places, found their way to a direct importation into their own ports, and though there are still two considerable manufactories for dressing flax here, and large quantities imported, both for dressing and selling rough, yet this branch has greatly decreased in comparison with what it once was; and the Baltic trade now chiefly consists in the articles formerly mentioned.

The commerce of this town with the Baltic, as well as that of Leith, Grangemouth, and some other places on the east coast, was greatly enlarged during the war with America. That country had been use to supply Britain before the war, with large quantities of timber, iron, tar, pearl and pot-ashes. The American trade being suspended by the war, not only all these articles were imported from the Baltic to this east coast, and by the merchants on this side of the island; but those of the west, to save the risk of capture in a circuitous voyage round the highlands, made the importation of those goods into the Frith of Forth, to be carried from Bo’ness and Grangemouth, through the great canal, to Glasgow. Great quantities of tallow and hemp were also brought over during this period. The trade then enjoyed by this and other ports in the neighbourhood, was happily improved, to furnish the means of an extended commerce for several years after the peace was concluded, A.D 1783.

It is only since 1793, the commencement of the present French war, that the trade of this town has decreased, in common with the commerce of other ports trading to the Baltic; and there is every reason to hope for a revival, when the blessing of peace shall be restored; an event earnestly to be desired by all the friends of human kind.

The corn trade, both British and foreign, is very considerable here. In 3 large granaries, and in some smaller ones, there is very good accommodation for above 15,000 bolls.

Grangemouth, South Queensferry, and North Queensferry, St David’s, Inverkeithing, Lime-kilns, Torry, and Culross, are united to the Custom-house of Borrowstownness; but the annual revenue received, excluding these creeks, will, on the average, amount to about L.4000. The salt-duty amounts to about L. 3000 per annum. The business of the Custom-house employs about 44 officers.”

In 1794 a further Act of Parliament was obtained whereby the Trustees were authorised to levy a small anchorage duty and to make a dock for repairing vessels. The size and design of the harbour had evolved significantly over the years, responding to the increasing demands of the trade. Additional facilities, such as the waggonway and cranes, meant that it remained up to date, and that was to continue well into the 19th century. That continuing story will be told in “Bo’ness Dock 1800 to the present day.” Up to 1800 it may be summarised as follows:

| 1710 | Wooden pier. |

| 1716 | Pier rebuilt in stone. |

| 1733 | 386ft East Pier added. |

| 1744/6 | Clean & deepen east side of Wester Quay. |

| 1752 | Addison’s granary on East Pier St; also Regent House with offices for Customs, |

| 1762 | Dr Roebuck extends coal fauld to N. |