The Water Supply of the Falkirk District 1860-1950

At the beginning of the period covered by this study the vast majority of people living in the Falkirk district got their domestic water supplies from wells or streams. The wells in the town centres were public, fed from a combination of natural springs and water piped from coal pits. Those in the villages and rural areas were largely private wells (see wells). Due to its low-lying position on the flat coastal plain things were different at Grangemouth and there the water came from the Forth and Clyde Canal.

Modern ideas of sanitation and disease were only just making headway and little effort was made to keep the water clean. As early as the late 17th century the burghs of Falkirk and Bo’ness had forbidden the washing of fish and other noxious items at the wellheads, but that was as much for the smell as anything else. At Denny the cattle were allowed to stand in the dipping wells, and at Grangemouth the inhabitants went to the canal with a slop bucket in one hand and an empty bucket for drinking water in the other. They threw the slops into the canal from one and then filled the other.

Of course, people complained when the water was muddy, or when it smelled badly, as these made it unpalatable. Larger creatures, such as lizards and frogs, were picked out, but there was no screening. Frogs occasionally blocked the pipes. Mud was allowed to settle out in storage areas, and there were regular complaints at Falkirk when miners disturbed the old workings used as a subterranean reservoir. Stoups filled with water from the Cross Well in Falkirk were allowed to stand on cool stone blocks within the houses so that the extraneous matter could settle out and any odours dissipate.

In the mid-19th century both Falkirk and Bo’ness got most of their water from coal pits. This was an old system at Falkirk and dated back to at least the 1790s when the natural springs in Callendar Park were abandoned, and then for a moderate sum of money the rights were sold to William Forbes. The water issued from the pits at what was referred to as the fountainhead, located at the top of Drossie Road a little below the site of the later railway station. From there it was led into the town first by wooden pipes, and then by lead and terracotta pipes, and by the middle of the 19th century by cast iron pipes. The use of cast iron revolutionised the distribution of water. It enabled better pressure to be achieved at the wellhead, and the use of siphons allowed it to defy contours between the source and the delivery point, as long as the former was higher than the latter. At Bo’ness the old wooden pipes had been unable to cope with the high water pressure which resulted from the introduction of water from St John’s Well high above the town at Borrowstoun in 1818. Cast-iron pipes were soon being mass produced and became a staple of the local foundries. This lowered costs and increased demand, allowing networks of many miles to be developed.

At Bo’ness the water was pumped out of the coal pits in the 1860s using gin mills powered by horses. Here, too, technological improvements came to their assistance and steam engines were introduced. Bailie Blackadder of Falkirk ran his own engineering business and in 1883 offered to provide a pump at his own expense to obtain water from springs near Camelon. In the end the source used to augment the town’s supply was an old pit at Summerford. The plant, which cost £3,560 in 1886, pumped 70,000 gallons a day.

Cost was one of the main limiting factors. Since 1683 the Stintmasters in Falkirk had been given the privilege of raising stints (stents) or taxes within the burgh limits to pay for the maintenance of the water supply which started with the Cross Well. Even so, they struggled to raise sufficient money and for larger projects had to obtain loans which were secured against future tax revenues. Later on, stintmasters were also to be found in Denny, but at Bo’ness the responsibility devolved onto the Town and Harbour Trustees. Villages like Larbert and Camelon had well committees that garnered funds by voluntary subscription (self-interest). Grangemouth remained under the control of the Dundas family until 1872 when water was one of the determining factors that led some of the leading citizens to create the Burgh using the Lindsay Act. In the rural areas people had to fend for themselves, though this tended to be easier as there was less competition for the resources and streams are plentiful. Eventually their interests were looked after by the district committees of the county council which Parliament recognised as the water authorities. The Local Government Act of 1889 allowed the previous small water authorities at the parish level to combine to undertake larger water schemes and so Stirlingshire County Council immediately promoted a water district comprising the southern portion of East Stirlingshire including such places as Laurieston, Polmont, Polmont Station, Brightons, Rumford, Maddiston, Standburn, Avonbridge, Slamannan, Greenhill, High Bonnybridge, and Bonnybridge. The total population in this area was around 10,000.

Parliament also played an important role in later schemes which were on a far greater scale and involved huge sums of money. It gave the water authorities powers to acquire land and borrow the money. Acts of Parliament and Provisional Orders came at a cost of their own and if one failed to get through the system it was an expensive mistake. In the early days the loans were taken out from local businessmen or wealthy families within the community. As the schemes became more extensive the larger sums involved were borrowed from the markets, usually based in Glasgow or Edinburgh. Latterly central Government provided loans at low rates of interest in order to enhance the health of the population and in the 1920s even provided grants to aid the projects as part of its unemployment policy.

By the 1860s it was recognised that water supplies had a bearing on the spread of debilitating diseases like cholera and enteric fever (typhoid). At Grangemouth in 1868 it was noted that those supplied directly from the canal were less likely to catch typhoid fever than those supplied from the reservoir of the timber basin. Small creatures were observed in the latter’s water and before long it became routine for a public analyst to inspect water supplies under a microscope. Councillors had to justify the amount of money spent upon the early extramural reservoir schemes and were able to point out the only too apparent health benefits. Within a decade of the introduction of water from outside the towns of Falkirk, Bo’ness, Denny and Grangemouth, the death rates fell dramatically and fewer developed serious sicknesses.

For centuries water had been impounded for the use of corn mills and later for saw mills and other industrial purposes. As a result, water rights were keenly preserved and contested. Larger reservoirs were needed to feed into canals. The Black Loch near Slamannan was enlarged at the end of the 18th century and fed water into the North Calder Water to Hillend Reservoir for the Monklands Canal and thence to the Forth and Clyde Canal (SMR 2016). Plans for a reservoir to the south of Falkirk on the Glen Burn for the Union Canal were never put into execution. Large reservoirs were also built in connection with works. Perhaps the best known in the Falkirk district are the Carron Dams belonging to the Carron Iron Company. These occupied a hollow next to the works which had been created by the much earlier digging of peat and was fed by a long lade from the River Carron. A second reservoir was built by the Company at Dunipace to cope with the excessively dry summer droughts. Ultimately the solution to the firm’s water requirement was to recycle it using a steam engine to lift the spent water back into the Dams. St Helen’s Loch at High Bonnybridge was enlarged in the 18th century so that it could serve a distillery and then a paper mill (Elves, Saints and Distilleries).

Some enlightened estate owners constructed small reservoirs or tanks to provide water to their tenants. The first tank at Carriden estate was probably an example of this and in 1860 the four-acre reservoir at the west end of Kinneil Park was formed. The consulting engineer for this was William Gale, who earlier had been consulted by the Bo’ness Harbour Trustees for the town’s supply in 1852. William Gale was renowned for his work on the Gorbals Water Works. His brother, James, was one of the leading reservoir builders of the era. He was responsible for the celebrated Loch Katrine scheme for the Corporation of Glasgow and was subsequently consulted by Falkirk in 1886.

Over the following decades the reservoirs got bigger. The first two reservoirs at Bo’ness, built in 1852 and 1878, were each just over half an acre in size. In 1884 new reservoirs of six acres each were added at Bo’mains and Carribber. Even these were small by comparison with the 1890 scheme of the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trust which consisted of three reservoirs of 22, 55 and 90 acres capacity. In 1860 this would have been an unimaginable scale of work, but was only a portent of things to come. As water authorities amalgamated and the areas they served grew, so too did the projects, culminating in 1939 with the flooding of the Carron Valley to form a reservoir with a surface area of 940 acres. The table below shows this growth in capacity for each of the water authorities.

| RESERVOIR | AUTHORITY | DATE OPEN | AREA (Acres) | CAPACITY (Gallons) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinneil 1 | Kinneil Estate | c1820 | 0.96 | |

| Carriden tank (East) | Pre 1854 | 0.55 | ||

| Borrowstoun 1 | Bo’ness Harbour Trustees | 1852 | 0.57 | 1.14 million |

| Kinneil 2 | Kinneil Estate | 1860 | 4.15 | |

| Borrowstoun 2 | Bo’ness Trustees | 1878 | 0.55 | 0.75 million |

| Carribber 1 | Bo’ness Trustees | 1879 | 16 million | |

| Carriden 2 (West) | 0.54 | |||

| Bo’mains | Bo’ness | 1884 | 6.0 | 16.11 million |

| Carriber ext | Bo’ness | 1887 | 7.21 | 25.44 million |

| Bridgeness | H M Cadell | 1893 | 0.27 | |

| Lochcote | Bo’ness | 1900 | 200.5 million | |

| Broadside | Denny Burgh | 1890 | 7.2 | 21.7 million |

| Overton | Denny Burgh | 1902 | 3.6 | 11 million |

| Faughlin Burn | Falkirk & Larbert Trust | 1890 | 22 | 32 million |

| Little Denny | Falkirk & Larbert Trust | 1890 | 55 | 126 million |

| Earl’s Burn 1 | Falkirk & Larbert Trust | 1890 | 90 | 250 million |

| Earl’s Burn 2 | Falkirk & Larbert Trust | 1909 | 170 million | |

| Drumbowie | Falkirk & Larbert Trust | 1907 | 36 | 125 million |

| Loch Coulter | Falkirk & Larbert Trust / Stirlingshire and Falkirk Board | 1924 | 135 | 880 million |

| Carron Valley | Stirlingshire and Falkirk Board | 1939 | 940 | 4,300 million |

| Millhall tank | Grangemouth Burgh | 1876 | 0.7 | 1.35 million |

| Millhall reservoir | Grangemouth Burgh | 1897 | 7.0 | 15 million |

| Millhall upper tank 1 | Grangemouth Burgh | 1907 | 1.0 | 1 million |

| North Third | Grangemouth Burgh | 1911 | 118 | 400 million |

| North Third extension | Grangemouth Burgh & Stirling | 1936 | 134 | 740 million |

| Millhall Upper 2 | Grangemouth Burgh | 1940? | 1.8 total | |

| Millhall Upper 3 | Grangemouth Burgh | 1960 | 0.75 million | |

| Loch Turret 1 | Grangemouth, Perthshire & Clackmannanshire | 1964 | ||

| Loch Turret 2 | Grangemouth | 430 | 3,681.52 million | |

| Buckieburn | Eastern District Stirlingshire | 1905 | 26.9 | 156 million |

| Greyrig tank | Eastern District Stirlingshire | 1905 | 0.35 + 0.72 | 0.83 million |

| Limerigg tank | Eastern District Stirlingshire | 1905 | 0.37 | 0.18 million |

| Summerhouse tank | Eastern District Stirlingshire | 1909 | 0.4 | |

| Beecraigs | Linlithgow District | 1921 | 12.7 | 82 million |

| Carriden tank (west) | Linlithgow District? |

The design and construction of the reservoirs changed with the times. Most were built through the hard labour of a large number of navvies, many of Irish descent. They were a hardy breed, living and working in difficult conditions. As the reservoirs moved into the remoter hills the workforce was forced to live in temporary accommodation close by. This meant wooden huts with bunk beds. David Ronald, the Falkirk Burgh surveyor gives us a good description of the men and their living conditions (see Falkirk Water Supply). One of the most telling things that he casually mentions is that at the end of the project with which he was concerned the huts were set on fire and thousands perished – thousands, that is, of lice and other such creatures. Slow combustion stoves were provided for the winter months and yet still the men suffered from exposure when they walked to and back from the public houses in the nearest towns. By the time that the Buckieburn Reservoir was being built in 1901-1905 such incidents were reported in the press and so we know that three navvies died.

| March 1903 | Danial Mclachalan | County Donegal | died of exposure |

| February 1904 | Patrick McConville | Coatbridge | died of exposure |

| September 1905 | Thomas Green | died of a sore leg |

The navvies were notorious for drinking and fighting and private policemen were hired to keep order and to throw the men out of the public houses after closing time. This sometimes ended with the policemen being beaten up. Later schemes introduced licensed premises besides the huts, the profits going to provide the men with additional comforts. There was also a shop or convenience store in one of the huts, leased by a grocery merchant from a nearby town. The standards of the huts were greatly improved over the years as it became more and more difficult to attract workers to these dangerous projects. A cook was hired to feed the men working on Beecraigs Reservoir in 1920. In 1922 one local farmer near Loch Coulter is said to have commented: ““My, it’s a bonnie pass when they provide water closets for navvies.”

Light railways were introduced in the 1870s to make it easier to move heavy materials around and to reduce the damage to the neighbouring estates. Clay and stone were quarried as close to the reservoirs as possible, not always with good results. The stone used in the concrete at the Faughlin and Earl’s Burn Reservoirs was found to be inappropriate and was poorly washed

with the result that large parts of the work had to be redone. Clay had to be of the right type and that used at the Earl’s Burn was not – again causing much rebuilding. Other materials, such as the hundreds of tons of cast iron pipes, and machinery, was hauled over poor rural roads which proved inadequate for the task. Large payments had to be made to the local road authorities in compensation, and in one case major repairs had to be carried out to a road bridge.

In the late 1880s the use of concrete on a large scale was still being pioneered, but the difficulty of procuring stone for the Falkirk reservoirs at Faughlin and Earl’s Burn meant that the consulting engineer changed the specification to allow concrete to be used extensively on the overflows and spillways, with unfortunate consequences. The essential element of earthen embankments at this period was the puddle clay walls which were set at their cores. They had to be of good quality material and properly puddled so that the air was driven out, making the wall watertight. To form a seal with the bottom and sides of the valleys in which the embankments were set a trench had to be dug down to impervious strata. The puddle wall and trench were usually the most expensive component of the dams, but the early schemes seem to have been somewhat poor in estimating their costs due to improperly assessing the stratigraphy. Perhaps the worst example of this was at the Drumbowie Reservoir where Copland, the engineer, relied upon less than a handful of bores to determine the likely depth of the puddle trench. One of the bores hit hard rock around 20ft down and that was considered to be a sufficient foundation. Unfortunately, it had hit a large boulder set in clay and when it came to digging the trench it had to go down considerably further, reaching a maximum depth of 103ft. This narrow trench was shored up with timber but was a terrible place for men to work in. Even solid rock was not always a good foundation and sandstone could be porous. By the second decade of the twentieth century cement grouting of these underlying beds using pressurised air was introduced.

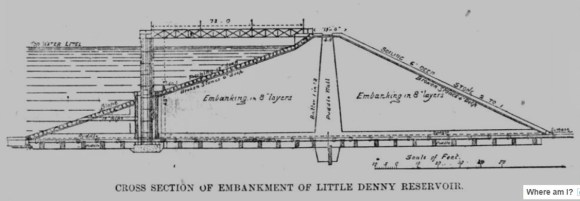

The following decades saw the replacement of the puddle wall with a core of concrete for the construction of new embankments. The earth to either side of these spines was built up in horizontal layers of a foot or so and each was well compacted before the next was added. Generous slopes were formed for their outer faces. The outer bank would then be covered with good quality soil and seeded with grass. The inner slope was covered with broken rubble and then hand-laid with pitched stone.

The quantity of earth shifted during the construction of a reservoir was immense. The first sod for the Faughlin Burn scheme was cut on 1 April 1889 and by the beginning of October about 400,000 tons of material had been shifted for the construction of the embankments at the three reservoirs. The road at Faughlin Burn had been diverted and the 200ft wide base of the embankment laid by the 106 men there. Around 50 men were employed on the Earl’s Burn Reservoir. At Little Denny reservoir about 126 men and 33 horses were employed.

The enormous embankment there was about half way up. It was 1,550ft in length, measuring 250ft broad at the base, and would eventually taper to 13ft 6in at the top which was 48ft high. Bogies on light railways were the main mode of transporting the earth, but the traditional wheelbarrow still had its place. By the time of the construction of the reservoir at Carron Valley much of this had been mechanised with steam shovels, cranes, and small locomotives taking some of the strain.

The overflow weirs on the early reservoirs were not very wide and were often interrupted by piers for the pedestrian bridges that crossed them. Experience soon taught the Falkirk and Larbert Water Trust that they had to be wider and uninterrupted. Ice that accumulated during the winter months was found to break into large pieces upon thawing and these blocked the weirs, resulting in the water levels rising dangerously high. The larger stretches of open water were also found to produce huge waves during gales which could overpower the weirs. Steel girders were used to span the wider gaps of the enlarged weirs. The spillways from the weirs had to be reinforced with either stone or concrete to stop erosion. Stepped bases for these reduced the water’s forward momentum.

Upon leaving the reservoirs the water was screened to remove the larger solid matter. The screens became of a finer mesh with time, copper being a favoured material for their manufacture. Sheltered clearwater tanks gave time for further material to settle out. The resulting water was cleaner than most communities had been accustomed to but where the water source was known to be polluted a further step was added. The water for the Old Town at Grangemouth came from the Forth and Clyde Canal and so the 1866 pipeline led to a filter gallery in the basement of one of the houses in Canal Street.

Such filters consisted of alternating layers of sand and gravel (or tile or brick). Falkirk introduced them in 1890 at Little Denny, but Bo’ness did not consider them necessary for its 1879 scheme at Carribber. It was 1900 before it placed filters at Hamilton Gate below the Bo’mains Reservoir. Denny, on the other hand, still did not require them for its 1902 works and only took filtered water when it was provided by an external agent. In 1964 Loch Turret was one of the first reservoirs in the country to use ozonisation instead of filtration to treat the water. It required far less maintenance and was cheaper to install. The ozone was produced using the dam’s own turbines.

Reservoirs are perhaps the most conspicuous component of the public water supply system but the distribution network is far more extensive consisting of hundreds of miles of underground pipelines. For the most part the water is gravity fed from the reservoirs which were located on the higher ground. In some cases the reservoirs were so high that it would have led to excessive water pressures in homes and so a series of valves and small intervening storage tanks evened out the pressure. These service reservoirs also provide a reserve of water and smooth out the flow in the event of blockages or bursts. Most are underground tanks which provide stable conditions for the water and avoid contamination or algal blooms. On the Continent underground storage is favoured as it considerably reduces evaporation, but that is not usually a problem in Scotland.

In his memoirs David Ronald mentions fishing at the reservoirs when they were first opened. Indeed, he placed a net over the scour pipe at one of the reservoirs to catch the fish! Some of the reservoirs were enlarged lochs and previously had fish, but many were deliberately stocked with fish, particularly brown trout. Sir Harry Lauder’s visits to Beecraigs Reservoir in 1928 helped to promote the activity there. Fishing took place at all of the reservoirs and sometimes resulted in prosecutions.

The increasing ease at which householders could get water naturally increased the consumption. In Falkirk in 1859 the average consumption per head had been 1½ gallons, shooting up to 8 gallons in 1872; by 1879 it was 10 gallons per head; and in 1899, 43 gallons. The figure in 1939 was 50 gallons, rising to 53 gallons in 1960. The demand from industry also grew rapidly. For those involved in processing food and drink the use of public water sheltered the businesses from the legal claims of their consumers in the event that contamination occurred. The 1920s witnessed an industrial boom in Grangemouth with Scottish Oils and Scottish Dyes taking huge quantities of water. These, together with further chemical companies, pushed the need for greater supplies and determined Council policy for a generation.

Some of the small reservoirs were decommissioned in the 1970s and were taken over by fishing clubs or syndicates. Carribber Reservoir changed its name to Bowden Fishery, after the nearby Bowden Hill. The upper reservoir, Bowden Loch, is about 2 acres in area, and is for fly-fishing only. The loch is well stocked with blue and rainbow trout. The lower reservoir, Carribber Loch, is regularly stocked with brown, blue and rainbow trout and covers an area of about 5 acres. Casting platforms are dotted strategically around the loch edge and there are a limited number of boats available to fly fishers. The filter bed system at Beecraigs was used as a trout fish farm for many years.

Today the large reservoirs looked after by Scottish Water welcome walkers and a large car park is provided at Carron Valley. They are all located in beautiful settings and since the 1920s the amount of woodland cover surrounding them has been increased. Perhaps one of the most dramatic locations is that of the North Third Reservoir with the rocky crags along its east side. Here a network of paths caters for the walker. Beecraigs Reservoir is now set in a country park and is a haven for wildlife. The only reservoir to promote water skiing was the Black Loch near Limerigg – but that was not a reservoir for drinking water.

Perhaps one of the most peculiar aspects of the story of the growth and enhancement of the water supply for Falkirk and district, giving us the resources that we now enjoy and take for granted, is that at every stage in its development it was opposed by sections of the community. And not merely upon the grounds of costs, but also because of the increased pervasiveness of central authority and even on ideals of health! Conspiracy theories are not new.