Prizes, Sweepers, Paravanes, Q-ships, Mines, Wrens, & Oil Pipelines.

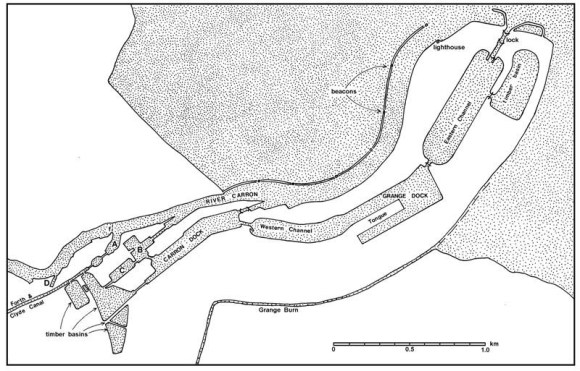

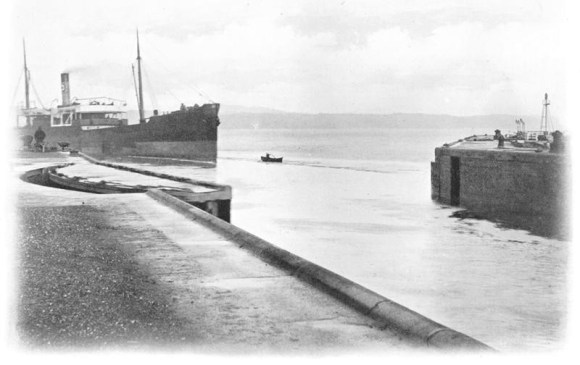

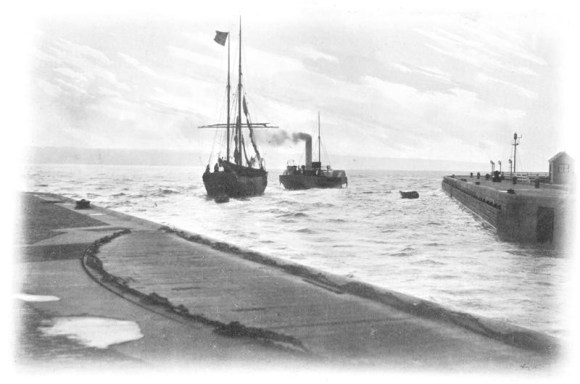

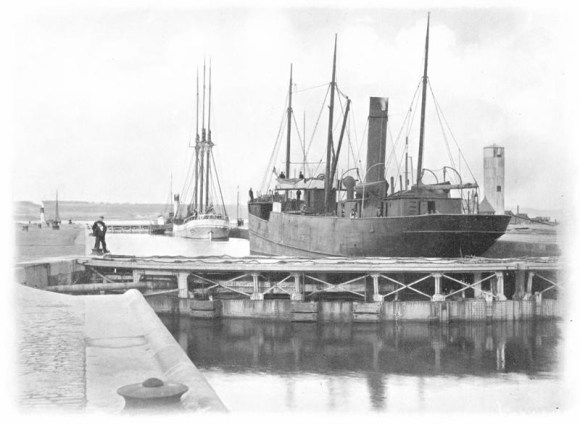

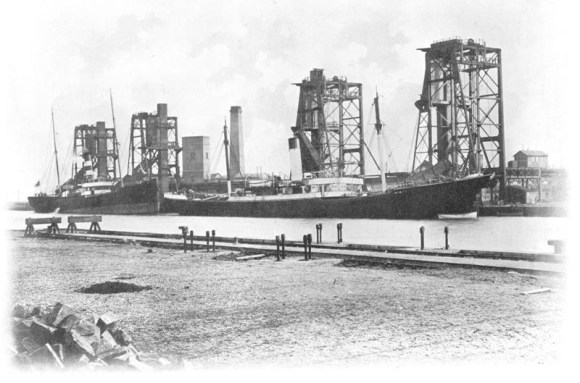

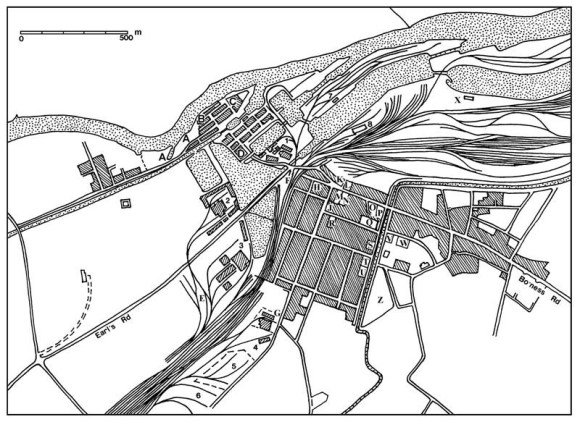

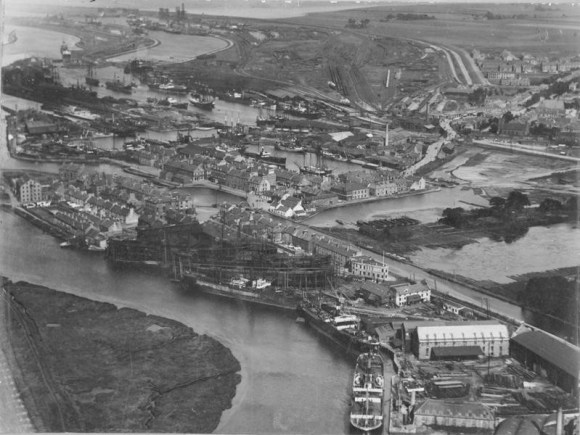

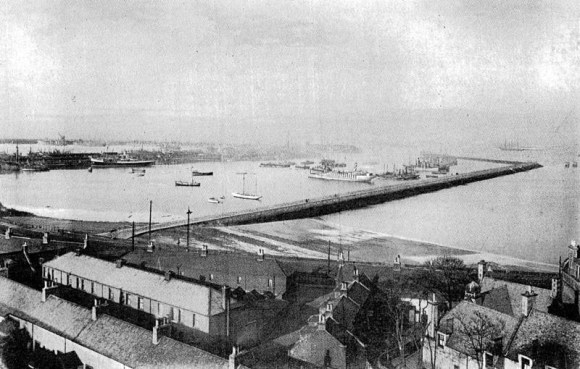

In 1867 Grangemouth Docks, along with the Forth and Clyde Canal, were acquired by the Caledonian Railway Company. The Company then set about using its vast resources to improve the facilities at Grangemouth in order to make it one of Scotland’s top three ports. Between 1867 and 1876 the tonnage through Grangemouth almost doubled and authority was obtained to construct a new dock. The Carron Dock was opened in 1882 and was a great success. By 1896 traffic through the port had risen to 2,418,878 tons. However, the Carron Dock still opened directly onto the River Carron and it was found to be impossible to dredge a sufficient channel depth due to the rapid rate of siltation. To maintain their lead the Caledonian Railway Company pushed forward with a massive expansion of the port. Work began in 1898 and by October 1906 the immense complex was ready for use. It included the Grange Dock of 30 acres and a large entrance lock to the Forth Estuary. In all there were nearly 100 additional acres of water in the port area. The effect of this great enterprise was soon seen in the tonnage passing through the port and by 1909 this had increased to 3.9 million tons.

Raw materials were imported from all corners of the globe to feed the industries of Central Scotland. The Falkirk area had become one of Europe’s largest centres for light castings and the ships brought iron ore and scrap iron in large quantities. Much of the iron ore came from Northampton and was brought by the Skinningrove Iron Company. Coastal trade was a significant component of the port’s business. Loam sand for casting came from the Thames Estuary. Chrome ore arrived from Scandinavia. China clay was used in the potteries. Esparto grass from Spain went to the paper mills at Denny. Kelp from Kirkwall and Christansund was processed into chemicals at Port Downie. Tallow and fish oil could be converted into soap at Grangemouth itself. Timber of all sorts arrived from the Baltic and from America. A large part of the port’s basins was devoted to this cargo, which arrived in various forms. Logs were processed in the numerous local sawmills and could be sent along the Canal, made up into rafts, for further work. Pit props were in high demand. Barrel staves arrived ready shaped for finishing work and assemblage at the cooperages. Wood pulp was another material destined for the paper mills.

A – Old Harbour; B – Old Wet Dock; C- Junction Dock; D – Dry Dock; F – Ferry.

Building materials flowed in both directions. Cement and slates came in and bricks left. Fireclay was being exported. The iron industry exported pig iron and manufactured goods such as stoves and ranges. Paper was consumed in large amounts in southern England. However, most bulk exports were also raw materials. Coal was perhaps the greatest by volume, some of which went in the form of coke. Pitch and oil were becoming increasingly important as exports. Even “mill cinder” found a use elsewhere.

To handle these cargoes a number of shipping companies and agents had been established in the port. By 1914 the main shipping agents with offices in Grangemouth were:

Anglo-American Oil Co; A B & Brown; Burrell, N; Buchan & Hogg; Carron Co; Robert Crawford & Co; J Currie & Co; J C Dick & Pollock; J & J Hay; Gibb & Austine; Gibson, George & Co; Gillespie & Nicol; Hopkin, Paton & Co; Love & Stewart; W Jacks & Co; J Livingstone & Sons; A MacKay & Co; Merry & Cane; Merry & Cunningham; Milne & Allan; J Rankine & Sons; J T Salvesen & Co; Shields & Ramsay; Skinningrove Iron Co; Walker & Bain;W K Watson & Co; P & J Wilkie.

Manual handling was still to the fore and these companies employed large numbers of casual labourers on a daily basis at the Docks.

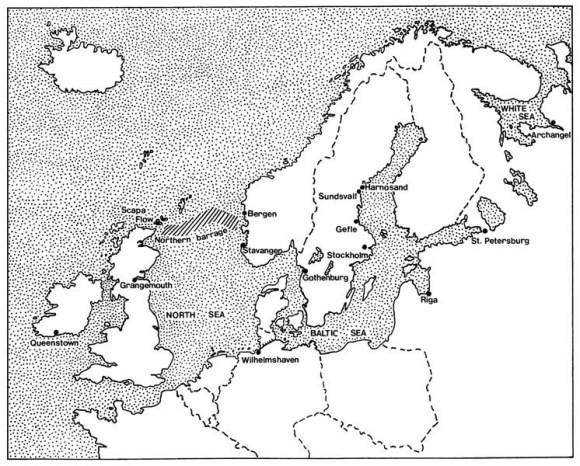

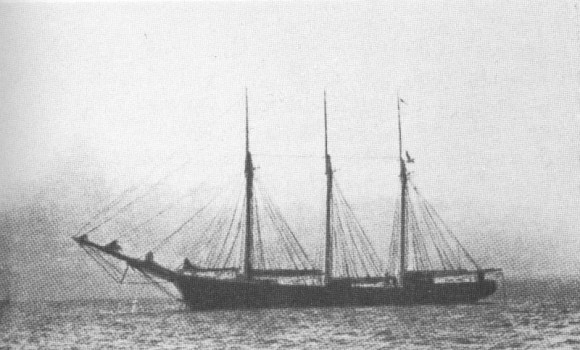

Trade was episodic and seasonal. A large part of the Baltic, for example, an important source of material brought to Grangemouth, could be closed between November and April each year by the build up of ice. Despite the distant threat of war with Germany, the Baltic traders were therefore reluctant to miss any voyages in the summer of 1914. J T Salvesen & Co was no exception. On 16th July the company’s ship Vala sailed from Stockholm and arrived at Grangemouth on the 30th. Vestra sailed from Grangemouth on 10th July to Gefle, Harnosand and Sundsvall, also arriving back at Grangemouth on 30th July. Embla left Hernosand on 31st July and arrived safely at Dundee on 6th August. These three ships were fortunate, for on 4th August Germany declared war on Britain. The four other ships of the Salvesen fleet did not have such good fortune. Germany had sent a naval force to the Baltic on 2nd August to seal off the Russian ports. Now it extended its blockade to include Danish and Swedish ports. 25 Scottish registered ships were thus bottled up, including Salvesen’s Vina, Siva, Duva and Driva. The Vina had sailed from Grangemouth on 30th July, arriving at Sundsvall on the 4th August. Siva put into Gefle from Oscarhamn on 31st July and Duva arrived there from Grangemouth on 3rd August. The Driva had just left there and made it safely to Sundsvall on 4th August.

It was obvious that the ships would be unable to sail home for some time and so they were laid up and the crews were reduced to one or two hands. The remainder of the crew were sent overland to Bergen and then by sea to Scotland, although the crew of the Duva only seems to have arrived back at Grangemouth in April 1918. By the middle of 1915 it appeared unlikely that any of these stranded vessels would be able to return to Britain during the war. Prices for second-hand tonnage had risen steeply and so J T Salvesen & Co decided to sell the Siva and the Driva. The former being sold to Swedish owners in November 1915, and the latter in October 1916. Sweden, Norway and Denmark were all neutral countries and consequently their territorial waters should have been safe. Britain was desperately short of mercantile ships and the Government encouraged those trapped in the Baltic to make their way home by way of neutral waters and a port on Norway’s west coast. Swedish crews were hired and the Vina made a clean break from Sundsvall on 8th June 1916. Two days later she was followed by the Duva. As she left Gefle a U-boat fired a torpedo across her bow to force her back into port. The crew called upon the Swedish navy to ensure her safe passage through their waters and she was escorted out by their destroyers. Both Salvesen vessels arrived at Gothenburg on 14th June. Here British masters took over command of the crews and on 17th June Duva sailed for the Tyne via Norwegian territorial waters. She was the first of the blockaded ships to arrive there on 22nd. Vina arrived four days later.

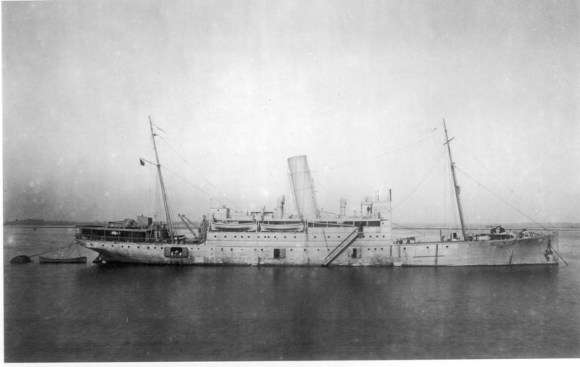

Many German merchant ships had been caught equally off guard by the declaration of war. HM Customs made a sweep of British ports looking for German registered or German owned vessels. Three – the Angela, Tilly and Hans Jost – were seized in Grangemouth Docks, and the Mientje was taken at Bo’ness. Subsequently the Mientje was taken to Grangemouth, where she arrived on 26th October 1914, to be laid up. The three ships at Grangemouth had already been joined earlier that month by the Katharina and the Hermann, confiscated at Wemyss, and the Wega and the Gebruder acquired at Alloa. Later that year these vessels were declared as prizes of war. Two further prizes, the Alfred and the Theodore arrived in March 1915 in order to be allocated to shipping companies to be managed on behalf of the Government (Appendix 1). In May the Katharina, Angela, Alfred, Mientje, Tilly and Theodore were all handed over to the Grangemouth company of James Livingstone & Sons and sailed to London with cargoes of bricks and fireclay. For the company this was to be the beginning of a long association with the Admiralty. All this went on secretly outwith the public gaze. By contrast everyone knew when the German steamship Nauta was captured and brought to Grangemouth with her cargo of timber in the first week of September 1914. The wood was consigned to local merchants.

Businessmen too had made little provision for the war. Andrew McKay, who had been the first provost of Grangemouth, had shares in a number of German ships, such as the Friedrich Carow and the Grete Cords. These shares were eventually liquidated by the German government.

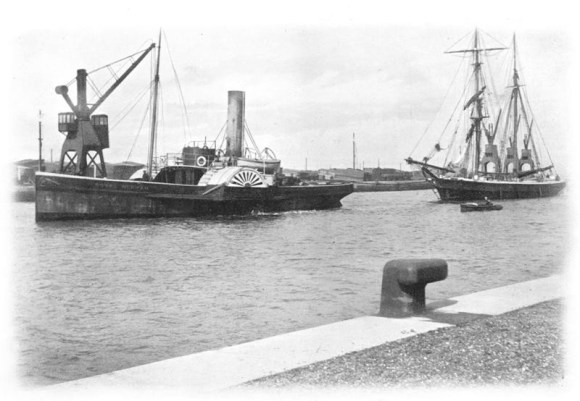

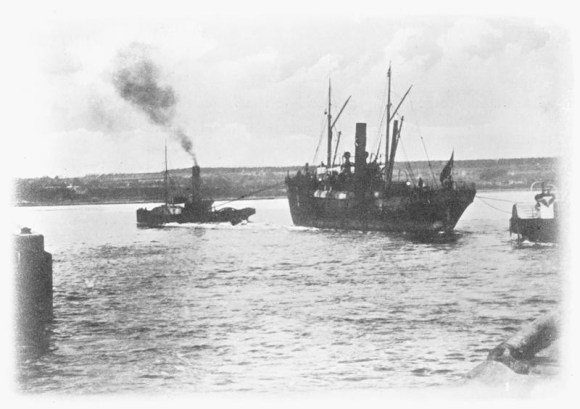

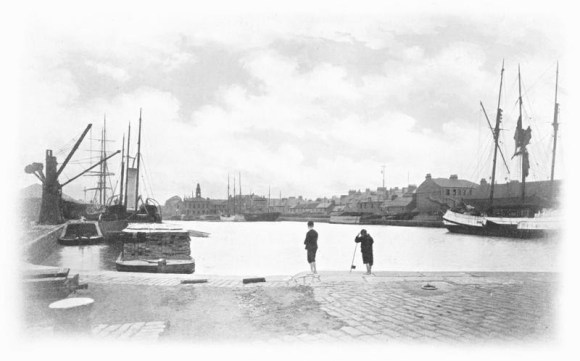

During the early summer of 1914 the paddle tug Forth, belonging to the Grangemouth & Forth Towing Company, had resumed her annual evening cruises from Grangemouth’s Old Dock.

Down river she went to Leith and up river she navigated the Windings beyond Alloa to Stirling. She was fitted out with deck seating and a canvas awning for her leisure role. Over the Falkirk Trades’ Holidays she had been joined by the Flying Bat and connecting trains were provided from Grahamston Station. Local firms chartered these vessels for their employees’ annual outings, as did societies such as the YMCA. However, from midnight on 2nd August 1914 the Admiralty declared the Forth Estuary to be a controlled area and pleasure excursions were prohibited until after the cessation of hostilities.

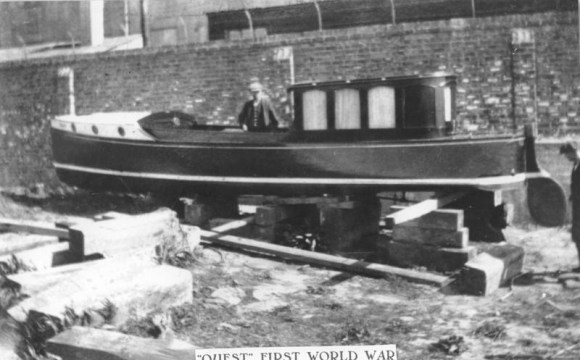

The Greenock and Grangemouth Dockyard Company already had a good working relationship with the Admiralty. In 1907 five horse boats had been built at Grangemouth, and in 1911 the Royal Fleet Auxiliary Burma was launched by the company at their Greenock Yard. When the war started, the most urgent demand of the Royal Navy was for minesweepers. These were desperately needed to sweep ahead of the large warships. Never before had mines been laid on the scale now seen. During the four years of hostilities the Germans laid some 43,000 mines and over 200 minesweeping vessels were sunk. In all, almost 3,000 trawlers and drifters were commandeered for this dangerous task, working as patrol craft, tenders to warships escorts, boom attendants and supply boats as well. They were manned by the fishermen, supplemented by naval officers. Within weeks of the war starting, drifters of 29-40 tons were brought to Grangemouth from Anstruther, St Monance, Cellardyke and Pittenweem. These vessels were registered at Kirkaldy and Anstruther. They were laid up in the Old Dock, where they were converted for their new role. This involved dismantling their fishing gear and installing powerful winches. Priority was given to the work and was undertaken by the engineers of Dundas Engineering (Tennant’s) and J Cochrane of Bo’ness, as well as the men of the Dockyard Company. The winches were brought through the Canal by the Dockyard Company’s own steam lighter the 20 ton Burnbank. Despite the original urgency, supply shortages meant that it was nine months before the last drifter left Grangemouth under the management of J Bonthron & Son (see Appendix 2).

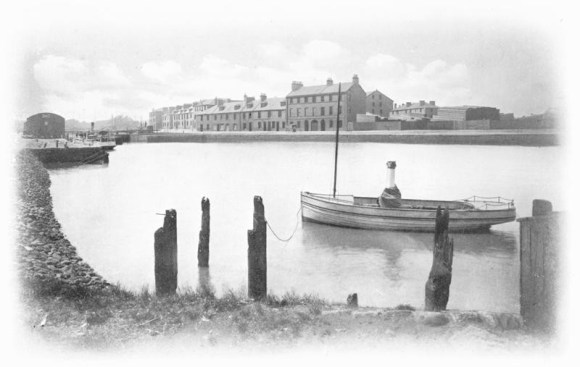

Whilst all this bustle and activity was going on in the Old Dock, the newer facilities were less busy. The SS Glasgow belonging to Rankine & Son, which had run a regular service from Grangemouth to Amsterdam and Rotterdam, was laid up before being chartered in December by G & W Burns to run from Glasgow to Liverpool. The Kerse Steamship Company had only been formed by Walker & Bain earlier that year and had just one ship – the Saxon Briton.

As she had traded to the Baltic she had to be employed in other areas. Buchan & Hogg of Grangemouth laid up their ship, the Dhu Heartach, in Alloa at the commencement of hostilities and sold her the following year. Before the war Thomas Cowan & Co had maintained weekly sailings to Southampton, calling at Treport for a return cargo. As the war settled into its familiar stalemate, the port of Treport had to be omitted due to its nearness to the Somme battlefront, and the number of sailings was reduced.

Trade began to stagnate. Even so, during the second week of November the Docks at Grangemouth were visited by 34 steamers with a total tonnage of 19,439 tons and by one sailing vessel of 205 tons (see Appendix 3). That week the North Sea was closed by the Admiralty to all British merchant ships. The area had been infested with U-boats and strewn with mines. Then, on 13th November 1914, navigation on the Forth was severely restricted. Ships entering had to report to guard vessels off May Island and submit to inspection. At the same time it was intimated that the Forth would close to all merchant shipping above Queensferry from 23rd November, closing the ports of Grangemouth and Bo’ness for the duration. This seemed to spell disaster for Grangemouth, which earned its living by the sea.

“We say: – No Thames, no London; no Clyde, no Glasgow. With equal truth we may add: – No Forth, no Grangemouth. For this reason it looked as if, by a single stroke of the pen, our means of subsistence had been filched away from us”.

Strong canvassing followed and the Town Council put together a delegation that included the powerful Carron Company to lobby Parliament and to persuade the Admiralty of the folly of its ways. Other local industries voiced their concerns and Bo’ness put forward a rather muted response. All were to no avail. The ports remained firmly closed and before long small craft on the river were not permitted any further east than Kincardine. The closure became known as “the unlucky Friday 13th”.

The pressure exerted by Grangemouth Town Council met with some positive responses. By the end of the month the Admiralty had set up a temporary Labour Exchange in the town to find work for unemployed dockers and men related to the Docks. It also offered to take men on at the rapidly expanding facilities at Rosyth, intimating that it might be possible to run a regular steamer service between the two ports for the workforce.

This service never materialised. Another Admiralty promise, to direct more of their work to the Dockyard to make up for the loss of work in the Docks, did happen. Amongst many others, the Dundee Council wrote stating that there was plenty of work in their docks for the Grangemouth men – though this may have felt like it was rubbing salt into a wound.

The closure of the Docks meant that those ships already there had to leave or risk being trapped by delays caused by red tape. Two of Salvesen’s ships, the Vestra and the Vala, had been laid up there since the last two days of July. Both sailed on 17th November. The Embla, after her narrow escape from Harnosand, had arrived at Grangemouth via Dundee on the 19th August. With her regular trade closed she too had been temporarily laid up.

Now, like most of the ships caught in the port when its closure was announced, she left without a cargo (see Appendix 4). Some of the cargoes en route for Grangemouth were considered essential to the war effort and so the Kinsale, Najaden and Samara were all allowed in. The Samara had deals from Archangel – useful for the manufacture of ammunition boxes, huts, and so on. Overtime was worked on the weekend of 5th and 6th December 1914 to clear these vessels. They sailed the following Wednesday and were the last true commercial ships for four years. For that long four year period the Docks were only used, with few exceptions, by the Admiralty and its shipping agent, W Mathwin & Son. One exception was the dredgers from Leith and Rosyth under the management of Topham, Jones and Railton.

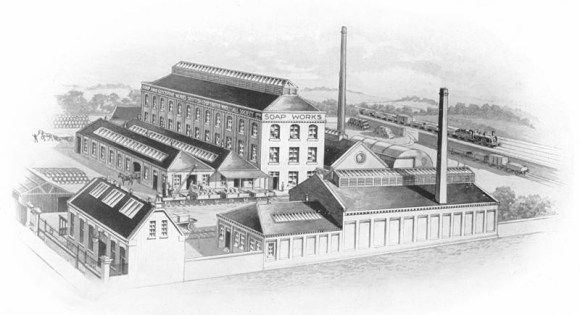

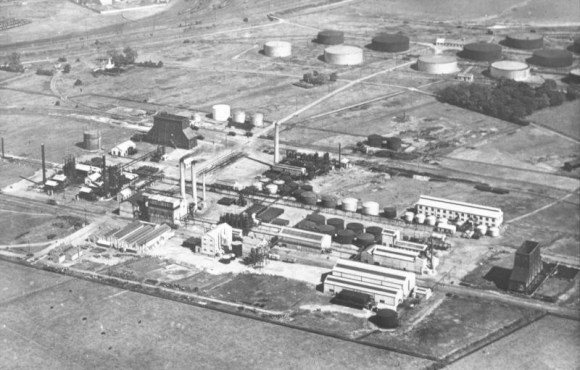

W Mathwin & Son took over the supply of caustic potash to the Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society’s Soapworks in Grangemouth. This supply was vital to the war effort, as glycerine was one of the by-products of soap manufacture and an essential ingredient in explosives. The works, in South Lumley Street, had been established since 1897 and were the second largest in Scotland. Peacetime supplies of caustic potash had come almost exclusively from Germany and the British Government put considerable effort into finding alternative sources. It took over the supply of raw materials to all the soapworks in Britain and controlled the Grangemouth plant. Despite the wartime restrictions, the SCWS works in Grangemouth were still able to turn out 130 tons of soap weekly – the total product for one year being 6,719 tons of soap and 320 tons of glycerine.

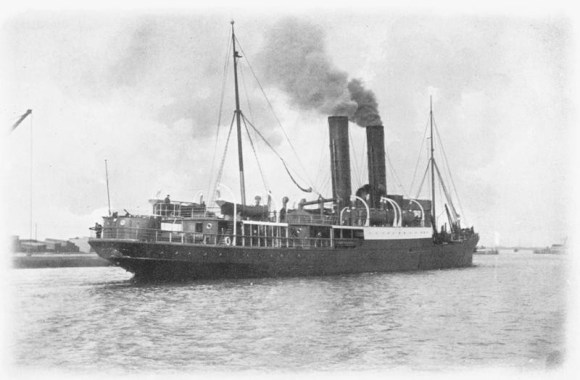

Before the war the Carron Company had a fleet of five ships sailing from either Grangemouth or Bo’ness to London. The passenger/cargo ships Forth, Thames and Carron were all relatively new and the Avon had been recently refurbished. The remaining ship, the Caroline, was a cargo vessel. On the day war was declared the Carron and the Caroline were in Grangemouth, where they were joined by the Avon four days later. The Thames and the Forth were at their base at Bo’ness. The Company suspended all sailings for two weeks until arrangements had been made to have the vessels covered by a new Government War Risks scheme. A convoy system of sorts was hastily put together and sailings of the Forth, the Caroline and the Thames resumed from Grangemouth. When Grangemouth and Bo’ness were closed to merchant shipping, the Carron Company transferred its Scottish shipping activities to Leith. This entailed hiring a new labour force at that port as well as lodging its clerical staff in the town at a cost of £1,175 per month. Goods had to be transported to and from Leith from Grangemouth by rail. Their trade suffered from a decrease in the tonnage carried and with the higher costs came a steep fall in revenue.

Thomas Cowan had little choice but to move his operations to Leith as well. He established an office at 34 Leith Walk, before moving to 125 Constitution Street. J T Salvesen already had family connections in Leith and so the move was easier for that firm. Denholm of Bo’ness did likewise. By the end of November 30 railway workers from Grangemouth Docks had already made the transition.

In February 1915 two of the dock workers who had been transferred from Grangemouth to Leith, being unfamiliar with their new place of work, fell into the docks there during the hours of darkness. One of them drowned. The following month the Caledonian Railway Company agreed to concessionary fares between the two ports to allow dockers to visit their families. By December the exodus was so complete that the Seamen’s Mission of Bethel in Grangemouth had to close due to lack of use. This once busy religious meeting hall and its reading room in South Harbour Street had been erected by the Marquis of Zetland in 1891 for the use of all nationalities frequenting the port. It had had its own resident Norwegian missionary, who held services on Sundays and Wednesdays, and a visiting missionary from Edinburgh for German seamen on Tuesdays.

All casual dock work at Grangemouth ceased and the council’s health officer noted that:

“large numbers of the healthy males of the burgh were transferred to Leith or sought employment elsewhere; the lodging houses, where over 300-400 unskilled labourers have been hitherto housed, became deserted – rapidly reducing the permanent population of the burgh – quite apart from the reduction consequent on the enlistment of at least 560 men in His Majesty’s Forces.” (February 1915).

At the beginning of December 1914 the Grangemouth Branch of the National Union of Dock Labourers reported that out of the 1400 members on its books on the outbreak of hostilities, some 500 were already either at the Front or in camps preparing to go there.

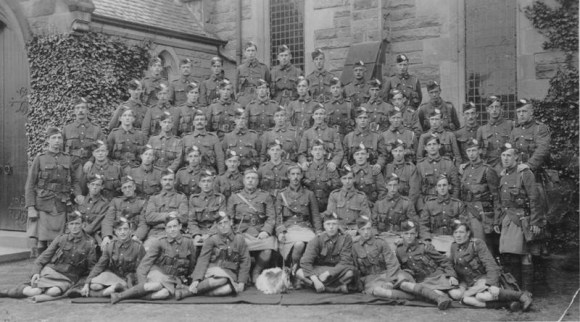

At the very beginning, on 4th August 1914, Grangemouth’s 65 Territorials and their two officers had been mobilised. Two days later they marched out of Grangemouth to Stirling, under the command of Captain (afterwards Lieutenant Colonel) Henry Wilson, and Lieutenant (afterwards Captain) George Ritchie. These men, after a few months of training, went to France in April 1915, and were known as 2nd Coy. 51st Divisional Train. Recruiting went steadily on until the number on active service rose to 1,655 of whom 281 made the supreme sacrifice.

The port became a prime recruiting ground for the Army Service Corps, which was looking for men to help with the supply logistics of the army in France. Even before the port closure announcement, a large number of recruits left in the first week of November for the No. 2 (Home Service) Company of the Army Service Corps (Territorial). In January 1915, 90 dockers left for France as Transport Workers with the Army Service Corps to undertake stevedore work and to help with the formation of supply roads. In May, 80 more men from the Docks and the local sawmills went for transport work. A final detachment of 40 men left Grangemouth by train for work in France that July. The town’s ultimate contribution to the road building programme in France came early in 1918, when the Town Council sold its old heavy steamroller to the Army for £525. As it had cost less than £490 when new, this was sarcastically referred to as quite a patriotic act! It allowed the Council to purchase a lighter roller, more suited to the tar that it was now using on the local roads. The slack in trade at Grangemouth Docks gave the government an opportunity to request equipment as well as men for handling material at the French ports. Six of the Caledonian Railway Company’s 2-ton hydraulic cranes at the Grange Dock were dismantled and sent to Rouen in March 1917. The work of dismantling and of reconstruction in France was done by the company’s hydraulic foreman, who, at the beginning of 1919, was sent again to dismantle the cranes for their return to Grangemouth.

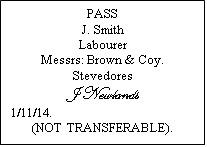

Whilst the dockers and recruits had been vacating Grangemouth, army personnel had been moving in. Eight days after the declaration of war a military guard had taken up post at the Docks. At night they used a system of passwords and countersigns, which they shared with the customs officials. Any civilian wanting to enter the area thenceforward had to obtain a pass. Brigadier-General S A Hare, Commanding No. 3 Brigade Area, was responsible for security at the Docks and he insisted that only one form of pass should be used, in order to make the task of checking them easier for the sentries. All passes were to be signed by J Newlands, the dock superintendent for the Caledonian Railway Company. Accordingly, on 23rd October 1914, Newlands wrote to all users of the Docks:

“It has been arranged that on and after 1st November, 1914, the existing passes to the Docks, including the recognition of Dock Labourers’ Badges, will be discontinued, and no pass will be recognised by the Sentries on duty unless it bears the signature of the Canals & Docks Supt.

There will be separate passes for day and night; the day pass will require to be of white paper; and a very limited number of night passes, of red paper; these should bear the name and designation of the bearer, together with the name of his employer.”

An example was given:

At first the officers of the Dock Guard, commanded by Captain William Bird of the 7th Scottish Rifles, were billeted in the still immobile SS Avon. On 17th September they borrowed a dinghy with two oars and a boathook from the Customs House to get to the ship. By the 24th October the Customs officials wanted the rowing boat back and suggested that the Carron Company ought to supply one. Captain Barclay of the Avon did not have a suitable boat, and in any case the ship was to resume her travels on Sunday 28th and would no longer be available for use as quarters.

British shipmasters and friendly aliens were to be supplied with passes by the harbour master, the aliens also requiring a customs pass. The Collector of Customs at Grangemouth, J B O’Sullivan, strongly objected to having to cede any authority to the dock superintendent and tried to pull rank, using his contacts at Rosyth and Queensferry. In the end, however, he too had to follow the military chain of command.

The Dock Guard still considered a boat necessary, particularly as the harbour master’s was out of repair. So they asked the Admiralty for a boat off one of the war prizes in the harbour and were given the use of a boat from the Angela, two oars, two rowlocks and a boathook from the Hans Jost, and a rudder from the Nauta. All of which were duly signed for by Captain Smith.

The Dock Guard stood sentry at the various entrances to the Dock complex and patrolled the grounds. The imposition of a black-out made guard duty rather hazardous for men unfamiliar with the local terrain. Early on the Saturday morning of the 21st November 1914 it was pitch dark and the weather was icy cold, “when the Territorial guard was being changed at the dock gates, and while a thick fog hung over the landscape, a cry of distress was heard proceeding from the water. One of the Territorials, Private Hugh Brown, D Company, 7th Scottish Rifles, who had just been released from guard, immediately divested himself of his overcoat and jumped into the dock. He was successful in saving the individual from whom the cry of distress had proceeded, and who turned out to be Mr Harvey, a water clerk [a Customs House officer]. Although a lifebelt was thrown in after private Brown’s jump, it was twenty minutes before they were taken out of the water, when both rescued and rescuer were naturally very much exhausted. Restoratives and other necessary treatment were applied in one of the customs offices, and by next day both men were said to be none the worse of their immersion. The rowing boat had proven essential.

All too often these incidents ended with a man drowning (see Appendix 5). In the first week of May 1915 the body of 32 year old Private David Carsel Wilson was found drowned in the Grange Dock. He was a Glaswegian in the 7th Scottish Rifles (Territorials). About 1.45am, he and another guard had heard the whistle of a ship using the Forth. The other man went to inform an NCO whilst Wilson continued the patrol.

On his return Wilson could not be found and a search was instituted. Over the coming months several more soldiers fell into the water and were rescued. Then, at the beginning of September, Private William Wilson of the supernumerary company of the Royal Highlanders (Second 7th Black Watch) and a companion fell into the Old Dock as they were retuning to their billets at 10pm. Other members of the Dock Guard heard their cries for help and were able to rescue the second man, but Wilson had vanished from sight. He had been a baker in Kirkaldy and was 37 years old. He was the third soldier to drown. The following week he was buried at Grandsable Cemetery with full military honours. A six-horse gun carriage was loaned by the Ayr and Galloway Artillery Battery stationed at Larbert and was accompanied by a uniformed guard of 200 composed of Royal Highlanders, Royal Scots Fusiliers and a detachment of the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders. The Royal Scots Fusiliers supplied a pipe band and were represented by their commanding officer. Captain Ovenden.

The long winter nights took their toll the following year. In October 1916 Private R Carlyle of the 205th CR Protection Company, Royal Defence Corps, drowned in the entrance lock to the Carron Dock. He had only arrived at Grangemouth the day before. Aged 50 years he was a native of Falkirk. The twelfth victim, Private William Archibald RDC, drowned later that month and was also buried with military honours at Grandsable.

The 2nd January following, Private Peter Troup of the 205th Protection Company was on night duty at the pier head. Around 3am he went to cross the dock gate, but unseen to him the tide had forced the gate open and he fell into the resultant gap. It was 3 months before his putrefied body was found floating in the Docks. He was 46 years old and from Aberdeen. It was not just the steep sides of the dock that presented a problem. Private Thomas Rankin, aged 55 years, from Gateshead, drowned in the Grange Burn. In a port accustomed to finding drowned sailors the casualties amongst the soldiers still came as a shock.

The water was not the only dangerous obstacle in the Docks. In August 1916 Private James Henry of the RDC was knocked down by a goods train during shunting operations whilst on sentry duty. He was taken to Craigleith Military Hospital (known as the Second Scottish General Hospital), Edinburgh, where his right arm had to be amputated at the shoulder. In November Private Gordon caught his eye on a spike of a swing gate at a level crossing in the dark. He too went to Craigleith, where his eye was removed. Both men were from Aberdeen.

From early in the war Grangemouth had been designated a Prohibited Area, which meant that no enemy aliens were allowed in the town or docks. In practice this led to all foreigners in the Docks being challenged by the guard. In August 1914 a Russian Finn from one of the ships threatened a Territorial sentry at the entry to the Docks. His abusive manner and the heightened tension of an invasion threat almost got him shot and it was only the admirable constraint of the guard that stopped the offence becoming a “sudden death enquiry”. On 1st May 1915 the exclusion was extended to all aliens irrespective of nationality. In July the order closing the area of the Docks to the public was more rigorously enforced. Prior to this it had only been applied in practice to the north side. Before long more fences were erected and extra sentries placed along the perimeter. Passes became harder to obtain and local businessmen faced further restrictions.

It was, of course, impossible not to have foreign seamen at the Docks, so passes were diligently issued and enforced. In September 1915 a Russian named John Richto and a West Indian named Louis Fay appeared at the Falkirk Sheriff Court. They were a fireman and seamen respectively on board the Government transport ship Pelica. They were charged with “having on 31st ult., on the south side of the western channel, Grange Dock, Grangemouth, near to Carron berth, they being required by Roderick Melville, private, No. 5 Supernumerary Company, Second 7th Scottish Highlanders, then quartered at the docks, Grangemouth, being a soldier engaged on patrol duty, to stop and answer to the best of their ability and knowledge any question which might be reasonably addressed to them, and in particular the questions as to where they were going and what were their names, each refused and failed to do so, contrary to the Defence of the Realm (Consolidation) Regulations.”

Another strategic location in Grangemouth that received a guard in 1914 was the water reservoir at Millhall. At the outbreak of the war the Falkirk Town Council and the Eastern District Committee of Stirlingshire had placed armed special constables at their water works at Buckieburn. This action prompted the Grangemouth Town Council to swear in two of their own men as special constables and to issue each of them with a double-barrelled breach loading shot gun and a revolver. The men were James Cowan, waterman, and Archibald Buchanan, a burgh employee. They were paid extra to undertake night duty at the water supply and were to challenge anyone in the vicinity after dark. The Council received a letter from Colonel Eggerton, commanding the Lowland Division, stating that such guards were unnecessary and displayed an “undue anxiety”. The Council continued the scheme for another month.

The anxiety over the possibility of an invasion or the presence of spies had other manifestations. The 15th Stirlingshire Boy Scout Group, which had been formed in 1909, met in the main hall of the YMCA in Abbots Road. With the outbreak of war arrangements were made by which, if necessary, the entire scout troop could be gathered together at short notice. They would then have assisted the regular soldiers by running messages and so on.

Throughout the first week or two of the war the boy scouts maintained posts at strategic points around the town – notably at the Avon Bridge. The aim was to intercept a German spy who was suspected to be moving in the area. In fact, the spy was arrested before getting that far. The scouts’ only success in this duty was the forcible stopping of an unregistered alien who failed to obey their summons. By the end of September 1914 a request was made for scouts to act as coastguards at stations all round the Scottish coast and, at a day’s notice, a fully-equipped patrol led by patrol leader Campbell Fisken was on its way to Fort George, Inverness, where it remained for eight months.

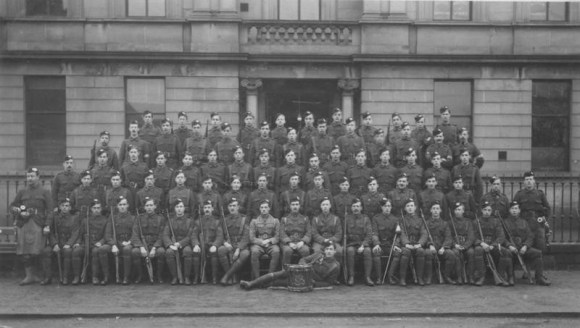

The decrease in the population of the port was made up for by the use of the town as a military billet. Early in September 1914 close on 1,000 men of the 7th Scottish Rifles (Territorials) arrived. Although they left on 21st May the following year, they were succeeded by the Royal Highlanders (second 7th Black Watch), who in turn left in the winter of 1915. Militarily, the parish of Grangemouth fell under District (No.10) administered by Major-General H L Gardiner, commanding Scottish Coast Defences. For a time a detachment of the Second 9th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders remained, but by the end of February 1916 the town was deserted. It was probably the presence of this garrison that led the German Prize Court at Hamburg to classify Grangemouth as a fortified port. Hence, according to a ruling of that court made in August 1915, which stated that it was alright for ships bound for fortified British ports to be sunk no matter what they were carrying or what nationality the ship, the closure of the Docks was reaffirmed.

At first there was a certain antipathy to the incoming soldiers by local tradesmen already smarting from the loss of trade at the Docks. This was heightened by the accidental shooting of a council employee going about the course of his duties on 4th December 1914. Before long the traders came to appreciate the large numbers of new consumers and were sorry to see them leave.

The shooting was particularly unfortunate and is probably best told through the words of the Falkirk Herald reporter:

“Widespread sensation was aroused in the Grangemouth district by a tragic affair, possessing extraordinary features and involving the death by shooting of a Grangemouth burgh employee, which occurred at an early hour yesterday.

The circumstances surrounding the startling affair are peculiar. It appears that one of the members of the 7th Scottish Rifles (Territorial Force), at present stationed at Kerse Parish Church Hall, who had been on sentry duty on Thursday evening, reported to his superior officer that he had heard a sound apparently resembling the discharging of a firearm from the direction of the Public Park and the Grange Burn. The sound, it appeared, was repeated more than once. In view of this report it was considered a desirable precaution against possible danger to sentries on duty to provide the latter with rifle ammunition, instead of as is customary, in the case of men merely on billet watch, to allow them to take up duty without having ammunition in their possession.

Two sentries were placed on guard, and at a time approaching 4am, while they were on duty, in the darkness which pervaded at that early hour, they saw, under what they regarded as suspicious circumstances, the figure of a man in the vicinity of Grange Burn. Challenging him, they received no reply. Then they discharged their loaded weapons in his direction, with the result that one bullet struck the man on the hand, and the other pierced his heart, killing him instantaneously.

The unfortunate man who met his death was James Waddell, 65 years of age, residing at 57 Dundas Street, Grangemouth. He was in the employment of the burgh engineer’s department, and was engaged in duties connected with his work when the painful affair occurred.

As a result of the heavy rains of this week flooding has been caused in the town, and the Grange Burn overflowed its banks, and in consequence of this – especially the overflowing of the burn – several employees of the burgh engineer’s department have been almost constantly on duty at the burn, for the purpose of doing what they could, by the cutting of trenches and the making of banks, to prevent water flowing into the Public Park. From an early hour on Friday evening three employees, one of whom was Waddell, were on duty together at this place. About ten o’clock two of them suspended work, and Waddell was left alone, his duty being to watch over the place till about half past five, when he was to be relieved. While he was thus engaged, about four o’clock, the tragic occurrence which resulted in his death occurred. At the time he was struck by the bullets he appears to have been in the act of lighting his pipe, for it and a match were found clutched in his hands.

Had the unfortunate man replied to the sentries challenge, it is obvious that the painful affair, with its pathetic result, would not have occurred. That he did not, however, is not perhaps surprising, as he is said to have been somewhat deaf.

As regards the sound resembling shooting heard on Thursday evening, the theory had been advanced that they were the results of the actions of some mischievous boys who had got hold of a weapon of some description and were amusing themselves on their way home. The sounds, it may be mentioned, were heard not only by the sentry who reported hearing them, but by other people in the town.”

John Waddell was buried in Grandsable Cemetery with an escort of 160 (the section based at Kerse Church) and members of the Town Council.

A sense of the activity and bustle that the presence of the soldiers created may be gauged by the following extract from the town’s roll of honour:

“A battalion of Scottish Rifles [Cameronians] was billeted in the town, under the command of Colonel Wilson, who, along with many of his men, fell at Gallipoli. Their presence made things hum and men in khaki were almost a more common sight than those in civilian dress. Great favourites these men became, and, when they marched away on 21st May 1915, the whole community was deeply stirred. As one thinks of these fine lads it is pleasing to recall that, while they were with us, everything was done to make them feel at home. The Burgh Court Building was transformed into a reception room, where refreshments were provided, letters written, games played – ladies and gentlemen giving ungrudgingly of time and strength to minister to their comfort.”

What the booklet does not mention is that the battalion was immediately sent to Gallipoli and on 28th June 1915 took part in the Battle of Gully Ravine, when it was decimated. The casualty figure was unusually high because the general in charge had decided to deploy his artillery elsewhere.

The practicalities of this large influx of men is illustrated less prosaically in the report of the town’s Medical Officer of Health:

“accommodation had to be found for them in such centres as would permit of proper discipline and economical arrangements as to commissariat, etc. At first the military authorities made a good many arrangements independent of the local sanitary staff, but especially since the issue of the Board’s circular of 10th September, there has been constant and harmonious co-operation between the civil and military officials. Despite the very varied degree of suitability of the buildings employed, the health of the troops has been very good. Some 3 cases of scarlet fever and 1 of diphtheria occurred at an early stage, in no way traced to any local infection. In December there was an epidemic of follicular tonsillitis among them. No one billet seemed to yield a large percentage of illness than another. Five church halls, the Town Hall, YMCA, and Rechabite Halls. Two lodging houses, a large railway goods shed in the docks, a large granary (of 3 stories), and several lesser stores, etc have been adapted – fitted when required with dry closetlatrines on an impervious base: cooking and washing houses – appropriate to the needs of each unit, have been erected. In certain cases heating pipes and electric light were introduced. At the close of the year arrangements were made to take over the Infant School for the use of the troops. Our cleansing department removes daily all excreta and refuse from these quarters. We have also disinfected by spray, when required on several occasions, and much work has been done at our hospital in the way of dealing (in our steam disinfector) with clothing and bedding infected with pediculi or scabies. A number of bacteriological reports have been made (especially during the epidemic of sore throats), and a weekly report of our sanitary state has been sent to our military medical headquarters at Bridge of Allan . I have also consulted with the military medical men in cases of doubtful illness among the troops.” (24 Feb 1915).

The Board’s circular of 10th September noted that

“The closet accommodation is in some cases inadequate and a special provision will be made behind the public Library, at the Town Hall, and between the Parish Church and Grange Churches. They have been using for this purpose improvised sand or earth closets with pails, which should also be emptied once daily. In addition they employ two handled tubs for urine, etc., to be emptied twice daily, in some cases, when convenient, into the street manholes. These will also have to be handled by our staff. It is also emphasised that this be done on Sunday as on week-days. If we choose in any case to relieve our staff by making a connection with a drain for any of these purposes we may find it well to do so, though no return for such expenses need be expected.”

Sand for the latrines was charged at 4s per load, including delivery. Removing the refuse and the contents of the latrines was done at cost. Water was provided at the rate of 6d per 1,000 gallons. This was not metered and the consumption was taken to be at the rate of five gallons per man per day and ten gallons per horse per day. The army furnished the number of men and horses weekly.

The first properties to be requisitioned that September were the Town Hall, public library, YMCA Buildings, Parish Church Hall, Grange U.F. Church Hall, Charing Cross U.F. Church Hall, Trades Hotel, Grange Working Men’s Home, and buildings in the Docks. The Kerse Church Hall and the Dundas U.F. Church Hall were soon added, as was the old granary in the Old Town. The Greenock & Grangemouth Dockyard Company fitted up 20 baths in one of its sheds for the Territorials to use. A military canteen was set up in Kerse Road. At the end of October the Infant School was acquired.

As the Victoria Public Library was occupied, the library leased a room in a new building on Station Road for use as a Reading Room. In June 1915 the lease of this room was taken over by Walker and Bain, shipbrokers, and the library was forced to move again. Upon the arrival of the Scottish Rifles, in September 1914, Mr and Mrs Harvey of Weedingshall paid for the Burgh Court House to be transformed into a soldiers’ institute. One of the rooms in the YMCA was also set aside for recreational use. The Town Council allowed some restaurants to open on a Sunday, but only to Territorials in uniform.

The Town Hall was originally let at £10 a week, plus the cost of any gas used. A month later, once it was realised that this was to be a longer term arrangement, it was changed to £22 a month plus the gas consumed. The Public Library cost £2.10s plus electricity. The Burgh Stables in York Lane, which were used to accommodate the horses of the 7th Scottish Rifles together with their stores and grooms, was rented at £5 a week plus the gas. When these billets were released at the end of February 1916 the Council claimed £17.9.6 for damages to the Town Hall and £13.4 for the Burgh Depot. In the event they accepted an offer made by the Military Authorities of £16 for the two properties. Damage to the Infant School was so extensive that at the end of the war the Scottish Command paid £85 in compensation. The Custom House and the Post Office remained in permanent military occupation by the Dock Guard until the last few months of the war.

During the military occupation of the town there were naturally numerous incidents of drunkenness and rowdy behaviour, but by and large the military and civilian populations mixed well. To reduce the effects of drunkenness the Defence of the Realm Regulations were stringently applied. The sale of alcohol to servicemen for consumption off licensed premises was forbidden. The publican of the Ship Inn fell foul of these regulations in August 1916 when he sold bottles to Private John Russell of the Royal Defence Corps for stocking the messroom of the Dock Guard. Other transactions took place. In November 1916 Thomas McFarlane, cooper and marine stores dealer living at Killin in Grangemouth, bought four cart loads of loose hay and chaff from Staff-Sergeant John Elrick of the Army Service Corps. This material was of too low a quality for the army to use and represented the sweepings of the stores. Large amounts of hay were stored by the armed forces in Grangemouth for shipment overseas. The officers believed that they had authority to sell the scrapings from these stores to local people and the court found that the position had not been made clear.

The Dock Guard became fully integrated with the local community, thanks to the efforts of their commanding officer Captain Ovenden of the 5th Royal Scots Fusiliers. When the Scottish Rifles had arrived in September 1914 they had immediately taken over the onerous responsibility of providing the Guard, and were in turn replaced by the Royal Highlanders. In November 1915 Captain Ovenden arranged for a large hut, measuring 68ft by 28ft, to be erected at the Dock near the offices of the Carron Company. The hutment had cooking facilities, lavatories, a bathroom and a counter where provisions could be sold. Upon completion it was handed over to the YMCA and staffed by local women volunteers who had agreed to provide the provisions. The women were to be conveyed each evening to the hut in a cab provided free by a local businessman. The YMCA Institute, as it became known, was officially opened that December. It quickly became the centre for many concerts that were organised to entertain the Dock Guard and the sailors still using the port. In this way money was raised for various good causes.

At the end of February 1916 the Dock Guard found themselves the only military left in the town. Lieutenant Greenary was transferred and the men settled in for a long tour of duty as second-rate troops. Permanent Dock passes were now issued to certain Grangemouth traders. When the Forth, a tug belonging to the Forth Towing Company, burst into flames in the Docks, the Guard assisted the Grangemouth Fire Brigade in putting the fire out. One of her crew fell into the water and was rescued by the Dock Guard. During the summer of 1916 the Dock Guard’s pipe band played at many local venues, including the convalescent hospital at Carriden House. However, by September that year significant numbers of the pipers had left for service elsewhere and Captain Ovenden made a public appeal for the donation of pipes so that they could be used by the older members of the Guard who had been left at Grangemouth.

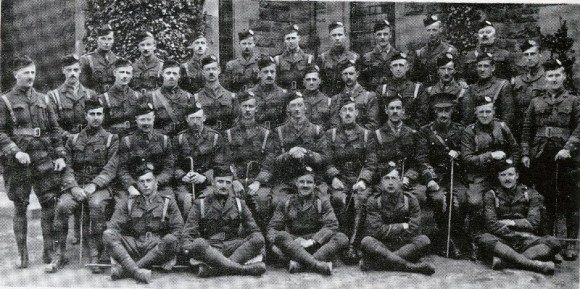

March 1917 saw the resuscitation of the Grangemouth Volunteer Company. This venerable institution had its origins back in the Napoleonic Wars, when the threat of invasion had also been high. It was, in many ways, like the Home Guard of the Second World War, consisting as it did of men not available for the regular army. As with the later Home Guard it started of as a voluntary organisation from which its members could resign under the Volunteer Act of 1863. However, as the war bit deeper and the population was mobilised for total war, this legislation was replaced by a new Act in December 1916 that stipulated that service was for the duration.

By 7th April 90 men had come forward. The following week the number stood at 120, and 135 the next week again. At the end of that month Captain Ovenden was awarded a military medal and received orders to take up a posting elsewhere. His sergeant, Sergeant Gallacher, went to Inchkeith. Lieutenant Florence took his place, but clearly the Dock Guard was being downgraded. The reason for this became evident in May, when it was announced that the Grangemouth and Falkirk Volunteers would take over the guard duty on the Docks at nights.

Captain William Simpson was made the commanding officer of the Grangemouth Volunteers, with Lieutenant Yuill as second in command. Walter Bain was made temporary Second Lieutenant in November. The Grangemouth Company was officially designated as “E” Company of the 1st Battalion Stirlingshire Volunteer Regiment. It originally comprised of sections A, B, C, D, R and P, but sections R and P were soon abolished throughout the country. They had consisted respectively of railwaymen and special constables, who were needed for other duties. Unfortunately for “E” Company this meant the loss of a large proportion of its membership and for a while it forced the prospect of amalgamation with another company. The last thing the men wanted was to become a section of the Falkirk Company!

The Volunteers took their task seriously and displayed a great esprit de corps, based as they were in the community. This is exemplified by their second route march in May 1917. This took them from the Old Town to Glensburgh, Bothkennar, Langdyke, Carronshore and back – a distance of 8 miles. Over a hundred Volunteers took part and were joined for part of the way by a crowd of local youths, including a three-year old. The youngster was not accompanied by anyone and having exhausted himself by reaching the Langdyke it was evident that the men could not abandon him. Willingly, he was taken up and carried to Bothkennar by an NCO, where he fell asleep. The charge was passed to a private, then two more NCOs, before being returned to his family in Grangemouth.

Rifle practice for the Volunteers was conducted at the Shelly Bank (the mudflats to the east of the Dock). The Volunteers commenced their guard duty at the Docks on the night of 4th June 1917. It was arranged that the Falkirk Company should guard the Docks on the nights of Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday, with the Grangemouth men covering on Thursday and Sunday nights. When the great day arrived the Falkirk Volunteers assembled at Grahamston Station and were given great coats and ammunition. They then boarded the 7.22pm train and disembarked at Grangemouth Station. A large crowd of well-wishers had gathered on the railway bridge at Station Brae beside the Dock entrance to cheer the Volunteers as they paraded past. Rifle practice for the Volunteers was conducted at the Shelly Bank (the mudflats to the east of the Dock). The Volunteers commenced their guard duty at the Docks on the night of 4th June 1917. It was arranged that the Falkirk Company should guard the Docks on the nights of Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday, with the Grangemouth men covering on Thursday and Sunday nights. When the great day arrived the Falkirk Volunteers assembled at Grahamston Station and were given great coats and ammunition. They then boarded the 7.22pm train and disembarked at Grangemouth Station. A large crowd of well-wishers had gathered on the railway bridge at Station Brae beside the Dock entrance to cheer the Volunteers as they paraded past. However, the Volunteers marched along the railway track under the bridge and proceeded, unseen, into the Docks. There they remained until 6.30am the next day. As the number of the Grangemouth Volunteers fell to only 127, which was not enough to cover the guard duty at the Docks, 30 men from Fallin were used to make up the numbers. Knowing that the usual guard on the Docks was 21 men and that the Company was there for two nights, we can assume that there were three watches a night.

All this time the Docks were made extensive use of by the Admiralty. It used it not only for coaling the Fleet, but also as a mine depot, a victualling yard and an oil-storage depot. The port was also available to the Government and War Office for storage purposes. The pre-war operating conditions had limited shipping arrivals and departures to a period of seven hours each tide; four hours before and three after high water. In order to prevent delay to HM vessels it was found expedient to withdraw this restriction, allowing access at any state of the tide.

As the number of the Grangemouth Volunteers fell to only 127, which was not enough to cover the guard duty at the Docks, 30 men from Fallin were used to make up the numbers. Knowing that the usual guard on the Docks was 21 men and that the Company was there for two nights, we can assume that there were three watches a night.

In October 1918 the Volunteers were relieved of their guard duty at the Docks and the task was taken over by special police appointed by the Military Authorities. There was a slight delay in obtaining uniforms.

Extra dredging was necessary to provide a channel to the entry lock. The gates on the entrance lock were kept closed, but the sluices were left open. Private Troup evidently had reason to believe that the gate was closed when he made his fateful journey across it (see above). Normally, the pressure of the water in the dock would have prevented the incoming tide from opening the gates, but this wartime measure cost Troup his life. The loss of constant pressure on the dock walls cannot have been good for their stability. Fortunately, these structures were still relatively new and the risk seems to have paid off.

The Government was concerned about bombing raids, sabotage and the possibility of invasion. It therefore decided to disperse the country’s food stocks. At different times between March and June 1915, a total quantity of close on 8,000 tons of Government flour was stored in seven sheds in the docks, the flour having been conveyed there by rail from various flour mills in England.

It remained in store for periods ranging from three months to seven months, and was then reloaded into the railway wagons and sent elsewhere. Food shortages began to tell on the civilian population. The Caledonian Railway Company made a special effort to induce its employees to cultivate allotments, newly formed from land within the fences of its railway lines and of the Forth and Clyde Canal. This facility was subsequently extended to non-railway men.

In 1915 and 1916 the War Office utilised five of the Dock sheds, several large timber sheds and some of the available land for the storage of hay. 19,000 tons of hay was brought in by rail and 14,700 tons were sent to the Continent or units in Britain. The quantity of hay required to keep an army in the field was staggering. The Admiralty also leased part of Salvesen’s large yard between the Caledonian Railway and Earl’s Road for the storage of hay. The yard measured 120 by 250 yards and in July 1917 contained ten large stacks with a total of 4,500 tons of hay. The stacks averaged 80ft long by 30ft high and were built from hundredweight bales. These conditions were, unfortunately, ideal for hot spots to develop producing spontaneous combustion. That seems to be what happened, for one morning at 7am a soldier spotted flames. The fire brigade was immediately summoned by phone, one being available in the adjacent woodyard of Brownlee & Co. By the time that the Grangemouth Brigade arrived the fire had a strong hold, fanned by an easterly wind. Even with the help from brigades from Falkirk and Glasgow it was impossible to stop the fire from spreading. All ten stacks and a neighbouring corrugated iron shed full of hay, measuring 40 by 100ft, were consumed. However, a similar shed loaded with timber was saved. The fire was characterised by the high flames and luminosity and was visible from Stirling. When finally brought under control the remnants of the stacks smouldered for days. It had been a colossal spectacle, but to the local farmers suffering from a severe shortage of fodder it was heart wrenching. The Admiralty rejected liability and refused to contribute to the cost of the fire services.

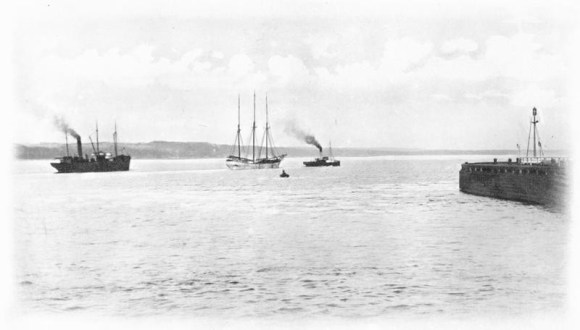

Welsh coal for the Fleet began to arrive by rail at Grangemouth on 10th August 1914 and huge quantities were received from then on for immediate shipment to Scapa Flow. At the core of the Grand Fleet were 24 advanced Dreadnought class battleships that could easily consume 30,000 tons of coal a month, especially as Admiral Jellicoe kept them at sea to avoid U-boats. Welsh steam coal was favoured by the fighting ships because it burnt with less smoke than that from other sources and so did not give away their position to the enemy.

It also had a higher calorific value than Scottish coal. Right up until the outbreak of the war the coal had been carried by colliers from ports on the south coast of Wales. The Admiralty had considered using rail transport to Grangemouth as early as 1911, but at the commencement of hostilities it did not even possess a single coal truck, nor did it have one on hire. By the end of the month it had secured 4,000 trucks on hire and had negotiated with the Rhondda coal owners for the fuel. The first of a regular series of wartime special trains left Pontypool Road at 12.35pm on 27 August on the 375 mile journey to Grangemouth. It was to be the first of many that became known as the ‘Jellicoe Specials.’

At first these trains supplemented the coal supplies carried up the west coast by the colliers. The colliers were vulnerable on this long trip and increasing numbers were lost to U-boats. The transition from sea to rail was gradual with additional trucks, two or three hundred at a time, being engaged as occasion required. Eventually the number on hire to the Admiralty for this purpose was 16,000. From Grangemouth the colliers, still at risk of attack, plied a slow 200 miles to Orkney. It was some twelve months before the port was adopted as the main base for the coaling of the Grand Fleet. The railway lines north of Perth simply did not have the capacity to deal with such loads and, in any case, were already crowded with naval personnel for Thurso.

Early in 1918 the traffic had assumed such proportions that an average of 79 special trains, carrying 32,000 tons of coal, were being run to various ports every week. Yet even this number proved inadequate and it was necessary to increase this by 30 for the conveyance of an additional 12,100 tons a week. 15 specials were run each day of the week, with four sent as convenient to make up the total of 109. This meant that good stores of coal for the Fleet were always available at Grangemouth and it was arranged that there was always a loaded stock on hand in case of emergencies. This was kept in 10-ton and 12-ton wagons ready for movement to any point in the docks. A further quantity was stacked as a reserve, to be loaded into trucks as required.

The total number of specials run from South Wales to the ports between 27 August 1914 and 31 December 1918 was 13,631. With an average of 40 trucks per train this was equal to 545,240 wagons. Allowing for 10 tons of Admiralty coal per wagon this gives an approximate total of 5,452,000 tons. Almost half of this was to Grangemouth. The normal sort of journey time from Pontypool Road to Grangemouth was a little under 48 hours. Thereafter, the empty wagons had to be returned. These were formed into longer trains, numbering only 8,161, though due to the acute shortage of rolling stock latterly many were given return loads by more circuitous routes. This was quite a feat of engineering and organisation.

Numerous ships were employed in the transport of coal, but the most frequent visitors to Grangemouth in 1916 and 1917 were:

| NAME | NET TONNAGE | No. OF VISITS 1916 | 1917 | HOME PORT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agnes Duncan | 1472 | 15 | 20 | Cardiff |

| Ashtree | 758 | 3 | 14 | Cardiff |

| Cedartree | 1012 | 2 | 20 | Cardiff |

| Constantine | 880 | 1 | 14 | Newport, Mons |

| Divis | 929 | 16 | 17 | Belfast |

| Ethel Duncan | 1091 | 16 | – | Cardiff |

| Fernhill | 1475 | 15 | 13 | Cardiff |

| Francis Duncan | 975 | 15 | 17 | Cardiff |

| Kawarra | 1215 | 12 | 22 | Liverpool |

| Mostyn | 1005 | 15 | 17 | Newport, Mons |

| Rotherhill | 1452 | 18 | 1 | Cardiff |

| Sheaf Arrow | 1175 | 8 | 20 | Newcastle |

| Simoon | 1365 | 20 | 1 | Newport, Mons |

| Singleton Abbey | 1526 | 17 | 2 | Cardiff |

| Slav | 1379 | 18 | 18 | Newport, Mons |

| Transporter | 868 | 20 | 22 | North Shields |

| Uskside | 1378 | 14 | 10 | Newport, Mons |

J T Salvesen’s vessel the Vestra was requisitioned as collier 447 and made her first voyage from Grangemouth to Scapa Flow on 17th November 1914.

.

Some Admiralty ships based at Leith and Granton were bunkered at Grangemouth. All work in connection with the handling of the coal was done by the Admiralty agents at Grangemouth. The total quantities dealt with down to April 30th, 1919, were:

| Received | 2,306,000 tons |

| Shipped | 2,092,000 tons |

| Stored on ground | 333,000 tons |

| Reloaded | 246,000 tons |

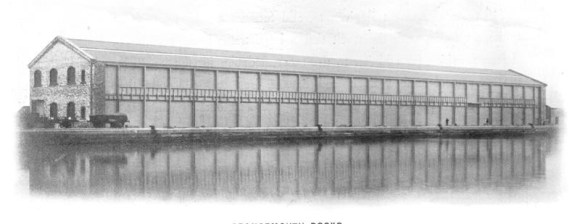

In June 1916 an Admiralty Victualling Yard was opened in Carron Dock, five sheds and some offices being taken over, either then or subsequently, for the purpose. The work in connection with the depot was done by a local firm of stevedores, who employed forty hands thereon. Up to the end of May 1919 over 51,000 tons of foodstuffs and stores for the East Coast fleet had been brought to the Victualling Yard by the Caledonian and North British routes, in addition to 9,000 tons which had come by sea.

Towards the end of the war steam lighters were in great demand to supply the fleet in the Forth and the base at Rosyth. One Grangemouth ship owner employed 21 men on such vessels in June 1917. A number of Carron Company’s steam and dumb lighters were employed on supply duties. In the six months to June 1918, the Company received £1,198 for their use (excluding the fee paid for Lighter No. 10, which was used to carry ammunition).

Over the half year to December 1918 they earned £1,395 and as the Fleet wound down this decreased to £872 for the period to June 1919.

J & J Hay’s 34 ton lighter Saxon was chartered by the Government and spent much of her time at Rosyth. She was in attendance to a battleship there, taking passengers and stores from the shore to the ship. As had become customary the sailors on the warship passed over some useless and damaged equipment to the crew of the tender. This material was then brought back to Grangemouth on the next occasion that her boiler had to be cleaned, in August 1917. Here the crew tried to sell the “scrap” and were charged with misappropriating Government property. As part of a general clamp down the crew of the tender Western Light (47t), owned by Hopkin, Paton & Co, were charged with the same offence. It became clear in the hearings that the collection of “scrap” had become a common occurrence, though it was not accepted as a “custom”.

Grangemouth was also on standby to receive injured servicemen via Rosyth in the event of a major battle, raid or evacuation. In March 1915 a Government motor launch arrived at the port from Rosyth carrying fever cases. It was met by an ambulance crew from Linlithgow fever hospital. However, news of the medical mission had become distorted and exaggerated, leading the port authorities to believe that a major incident had occurred. Several local doctors and 20 men from the Caledonian Railway Ambulance Brigade rushed to the dock side to greet the vessel.

Although the heavy cruiser squadron was based at Rosyth for much of the war, the capital ships of the Grand Fleet used the anchorage at Scapa Flow. This safe haven had not been fully developed when the war had begun and one of the chief difficulties lay in communications between there and London, the distance being too far for good wireless reception. Falkirk lay roughly equidistant between the two and a wireless relay station was set up in the fields between it and Grangemouth. Men from this signal station were part of the Naval establishment of Grangemouth. Jim Reid, a local resident, described the location:

“On the approach road into Middlefield there were three wooden huts and a very tall steel mast and I think two much smaller ones. This was during the 1914-18 war and the mast marked a wireless repeater station… There was always a small number of soldiers guarding the place and it was fenced. No one was encouraged to leave the farm road.”

A regular traffic in timber was dealt with at Grangemouth for the Timber Control Department of the Board of Trade. In peacetime timber had arrived in large quantities by sea from the Baltic and Scandinavia. During the war this trade all but ceased and most timber arrived by rail. Approximately 30,000 tons came by rail in this period and only 2,700 tons by water.

It was mainly stored on ground belonging to the Caledonian Railway Company in the Docks or, in the case of heavier timber, in the timber basins. Before the war, timber had been one of the main cargoes carried on the Forth & Clyde Canal. The closure of the port starved the Canal of its trade and meant that it was no longer of use as a cross-country waterway for commercial traffic. As a consequence a number of firms laid their boats off for the duration. Examples were:

| Leith, Hull & Hamburg Steam Packet Co. | 12 boats |

| Carron Co. | 5 boats |

| James Rankin & Co | 8 lighters |

| J & J Hay | 6 steamers & 20 scows |

| Wm Jack & Co | 5 steamers & 10 scows |

| J T Salvesen & Co | 8 lighters |

In any case, because the Government had taken over control of the railways and the Canal belonged to the Caledonian Railway Company, it had affectively taken over control of the canal. It was March 1917 before they took over all the other canals in Britain, using their powers under the Defence of the Realm Regulations. At least six of Salvesen’s iron lighters were sold in April 1916 to Rea Transport Co Ltd of London. These were the Dart, Express, Flash, Glance, Gleam and Prompt.

The canal could be opened when the occasion required. Early in August 1916 the Dutch fishing fleet was escorted from Leith Roads to Grangemouth for passage through the Forth & Clyde Canal. The herring were on the west coast. Almost 100 fishing boats were involved and must have formed an awesome spectacle as they made their journey along the canal (Appendix 6).

Some of the timber was used for making ammunition boxes in the local sawmills. Many women were brought into the works to deal with this monotonous task, though men still held key jobs such as wood buying and saw sharpening. In January 1917 part of the box department at Muirhead & Son’s sawmill was destroyed by fire. Production continued in other buildings and none of the female workforce was injured. In March that year a woman there was hurt whilst operating a crosscut saw. Wood continued to be used in Grangemouth for making and repairing barrels for munitions and the collection of scrap metal. One 38 year old cooper in the town was the sole proprietor of his business and therefore had his military exemption renewed as late as October 1918. Men involved in the timber trade – measuring, surveying, buying the wood and other skilled tasks – were also exempted. Some of the wood went to Bo’ness, where it was made into huts. The prefabricated sections were then dispatched to Grangemouth by rail for loading onto the army transport ship SS Sceptre and so on to France.

Trade on the canal was not alone in its decline. The passenger traffic carried to London by the Carron Company’s ships slumped from 9,545 in 1913 to only 3,252 in 1914, and even that low number was due to military personnel travelling to their units. As a consequence passenger services were terminated for the duration and in fact never resumed again. In 1915 the Carron Company reported a loss of £5,911 on its shipping concerns, despite receiving £10,412 from the Admiralty for the hire of the SS Carron. Worse was to come. On 9th April 1916 the Avon hit a floating mine laid by UC-7 near the North Foreland on the return journey from London. Captain Shaw and 29 of her crew were rescued, but two drowned. Later that year, on 9th December, the SS Forth was sunk by a mine off Suffolk.

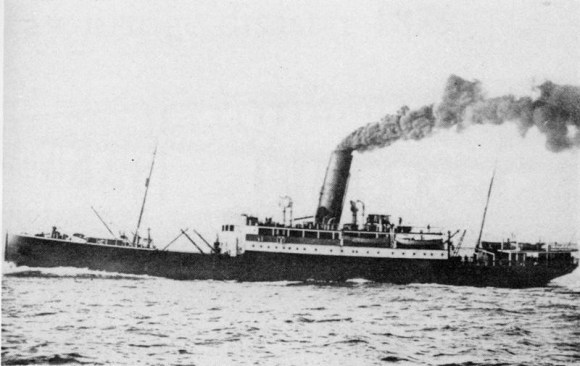

By this stage in the war the German onslaught on Britain’s vulnerable mercantile fleet was well advanced. For the first few months of the war the U-boats had restricted their targets to military vessels, but as Britain’s blockade of their ports began to bite deeply into their supplies they were given orders to retaliate. At first the submarines were expected to sink or capture British mercantile ships within the framework of international law. Accordingly each ship had to be given a warning and stopped so that her papers could be examined to uncover ‘contraband’, that is war supplies. If these were found then the ship could be sunk or taken prize, but only provided that the safety of the passengers and crew was ensured. Refuge in a lifeboat on the open sea was not considered sufficient. Sinking a merchant ship with people on board was only permissible if she had persistently refused to stop or had offered active resistance. The first British merchant ship to be sunk by direct U-boat action was the 866 ton Glitra on 20th October 1914. She belonged to Christian Salvesen of Leith and was outward bound from Grangemouth to Stavanger with a mixed cargo of coal, iron plates and oil. 14 miles from the Norwegian coast she was sighted by U-17, which pulled alongside the steamer and ordered the crew to abandon ship within ten minutes. A party of submariners then boarded the ship and opened her sea-cocks, sending her to the bottom. Mindful of international law, the U-boat then towed Glitra’s lifeboats for several miles before casting them free within easy reach of the shore. Less than a fortnight later Britain designated the North Sea a military area and escalated a long series of reprisals which resulted in the unrestricted submarine warfare that paid little regard to the accepted codes of war.

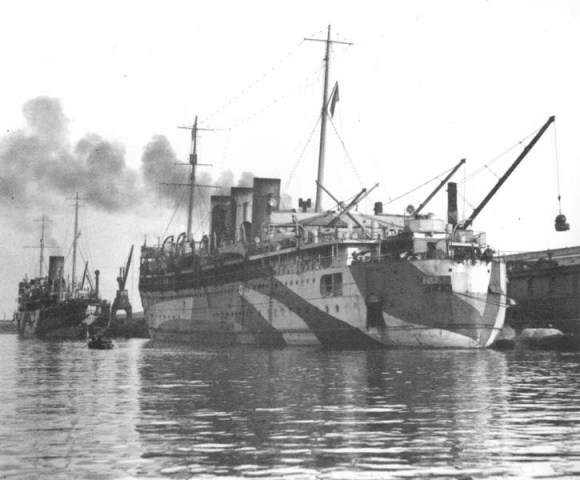

On 15th February 1918 the Thames was attacked in the North Sea by a U-boat, but the torpedo missed. She was not so lucky on 26th May that year, when she sank off Seaham as a result of another torpedo. Four lives were lost, including that of the master. Earlier that year the Caroline had sunk after a collision with a Newcastle steamer off Flamborough Head, Yorkshire. Ironically, of Carron Company’s fleet of five ships the only one to survive the war was Carron, which had been requisitioned by the Admiralty in November 1914. She was commissioned as a boarding ship and undertook patrols in the English Channel. In 1915 she supported the landings on the Dardanelles, and was there for the evacuation. From April 1916 she operated in the White Sea off Murmansk. It was 3rd January 1919 before she was finally paid off.

J T Salvesen did not escape unscathed. On Christmas Eve 1915 the Embla struck a mine in the Thames Estuary and became a constructive loss. While on passage from the River Tyne to Rouen with a cargo of coal the Vestra was torpedoed and sunk by UB-35 on 6th February 1917, 5 miles NE of Hartlepool. The Vala was torpedoed on 21st August 1917 while in Government service – more of which later. The Siva and Driva had been sold to Swedish merchants, after they had been forced to remain tied up in Swedish ports on the outbreak of war. The Duva was sold in January 1917 (and was torpedoed 14 months later). Out of a fleet of seven ships at the beginning of the war this left only the Vina. In February 1918 the Government placed the Cresco under the management of the company until she returned to her Norwegian owners in January 1919.

The losses mounted (Appendix 7a, 7b & 8). Walker & Bain’s ship Saxon Briton was torpedoed and sunk off the north Cornish coast on 6th February 1917. That same year, on 2nd November, the Jessie was attacked by a U-boat using its deck gun. Although beached she became a total loss. To add to the company’s disastrous year, David Walker, one of the partners, was killed in action serving with the Seaforth Highlanders.

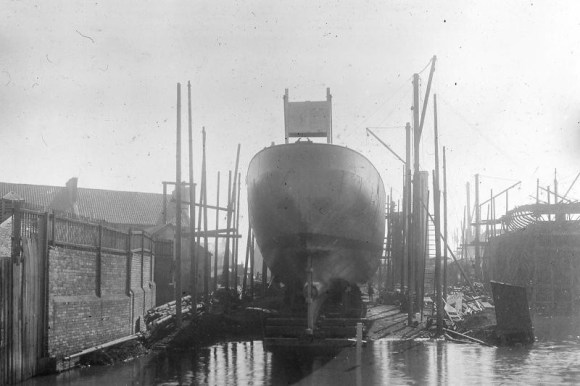

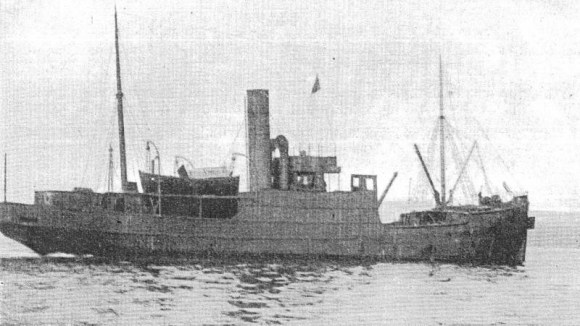

The loss of mercantile tonnage was tremendous and shipyards throughout Britain worked hard to replace it. Grangemouth Dockyard was particularly busy, as the Admiralty had kept its promise to direct work there. On 19th December 1914 Admiral Lay sent Captain-Engineer Percy to inspect the yard’s facilities, and those of the Dundas Engineering Company in the Docks. He found one vessel of 3,000 tons (the Traquair for George Gibson & Co of Leith) well under way and the keels of two steamers of 3,500 tons (the Denpark and the Hazelpark) laid down for J J Denholm of Greenock. Within weeks the Greenock & Grangemouth Dockyard Company received orders for a series of sloops for the Royal Navy.

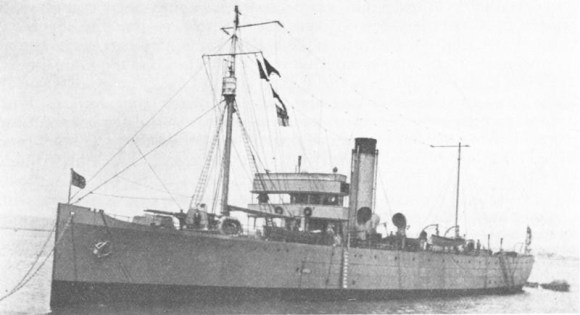

The first order came in January 1915 and was considered to be extremely urgent. The drifters being converted for minesweeping duties were not versatile enough and did not have the range required for the Grand Fleet. So 36 Acacia class sloops were ordered, three from the Grangemouth yard. Construction began immediately and the work on two of the merchant ships already underway had to be put aside. The Traquair was so far advanced that she was launched on 2nd February, but she was then sent to Leith to be engined before returning to Grangemouth for her final fitting out, which was only completed on 27th November. The Denpark and the Hazelpark were not launched until 4th March 1916 and 19th April 1916 respectively. Indeed the Hazelpark was not completed until October that year. Emphasis was placed on the minesweepers, which at that time of year meant working by artificial light. The dockyard was lit up and received many complaints that it was not observing the black-out, which was being enforced everywhere else including the Docks where men drowned for want of light. The Admiralty obtained a waiver.

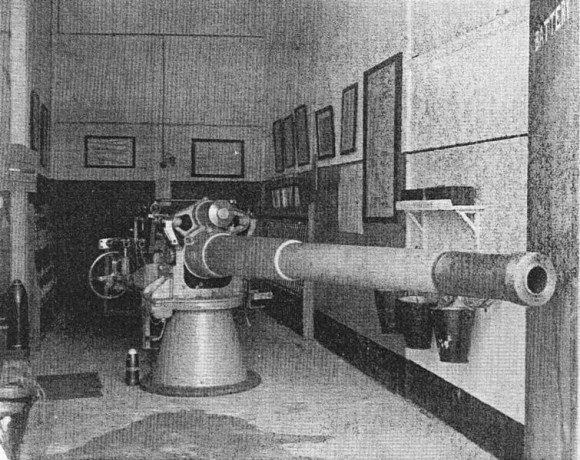

Considering that the Acacia type sloop had a displacement of 1,200 tons, measured 250ft by 33ft, and carried two 12-pounder guns and two 3-pounder guns, it is remarkable that the first was launched on 29th April 1915. She was HMS Lilac and her sea trials were held on 26th June from Inchkeith to May Island.

She was followed in quick succession by HMS Clematis, launched on 29th July 1915, and HMS Carnation launched 6th September 1915. These were fast ships. The Clematis achieved a mean speed of 16.5 knots on her trials on 7th October and the Carnation 17.4 knots on 4th November. They were therefore also used as convoy vessels to guard against the increasing submarine menace.

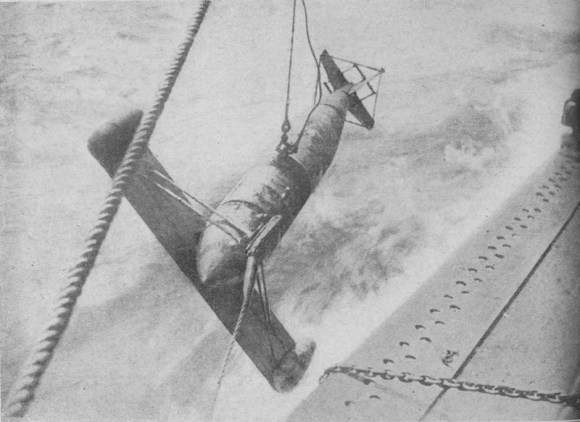

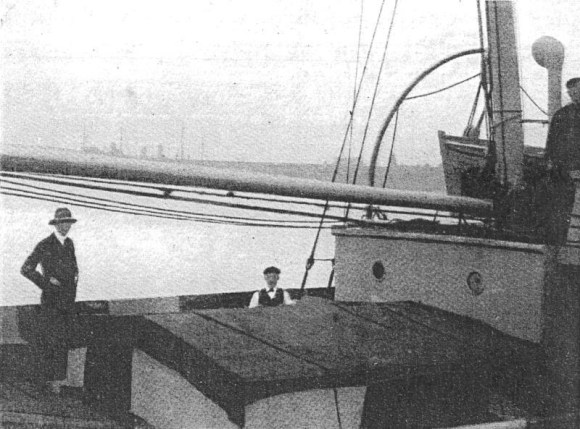

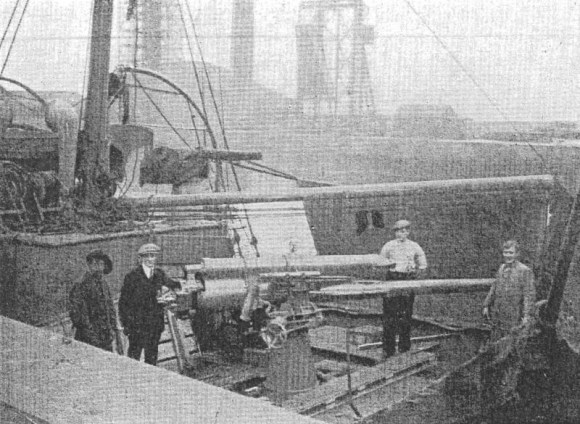

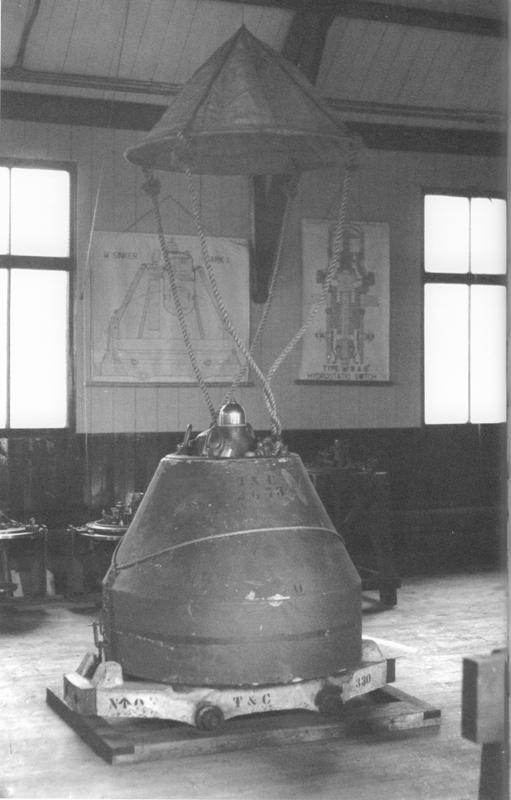

It was at this stage of the war that the Grangemouth Dockyard started fitting paravanes to Navy ships in order to give them a measure of direct protection against mines. It had been invented by Lieutenant Burney only months before and at first fabricated units were in short supply. “Kites” and floats arrived at the dock side by lorry in April and May 1915. All Royal Navy vessels were fitted in utmost secrecy and only then were they made available to merchant ships, which were also fitted out in large numbers at Grangemouth. The paravane worked on the observation that few ships ever hit a mine head on. Most mines exploded along the sides and not at the bow. The idea was to use a system of submerged wires to deflect the mines away from the sides and out to a safe distance. The paravane consisted of a torpedo shaped body fitted with hydrovanes, at one end of which was a float, and at the other end a weight. Towed in the water the hydrovane or “kite”, with its sloping metal surface, forced the paravane down into the water when the tow wire was taut, just as a kite rises in the air from the pull of its string.

It was equipped with a rudder that regulated the depth of flotation by means of a hydrostatic valve. The “Otter” paravane was used defensively. A pair of paravanes was towed, one on either beam so that the tow wires lay obliquely outwards from the prow of the ship. The wire was of strong flexible steel 1.5 inches or so thick. As it swept through the water this wire would come into contact with the mooring chain under a mine.

The mooring chain then slid along the tow wire, away from the ship, until it reached the paravane. The nose of the paravane was fitted with a heavy cutter bracket and serrated knife blade that, on contact, snapped the mooring chain and released the sinker causing the mine to rise to the surface. Here it was detonated at a safe distance by gunfire from the ship. The paravanes could be towed at most speeds and only reduced the progress of the vessel by a little over half a knot.

The next Admiralty order for minesweepers was for two Arabis type sloops, one from the Grangemouth yard and one from the Greenock yard. Both the Acacia and Arabis type were Flower class sloops, the latter being slightly larger at 1,250 tons displacement and measuring 255ft by 33ft 5in. Their armament consisted of two 4in guns (or 4.7in) and two 3-pounder guns. In all 36 of these were ordered from British yards. HMS Geranium was launched on 8th November 1915 at Grangemouth, and HMS Gentian at Greenock on 23rd December 1915. They too were initially fitted for minesweeping operations, but were later used for anti-submarine patrolling.

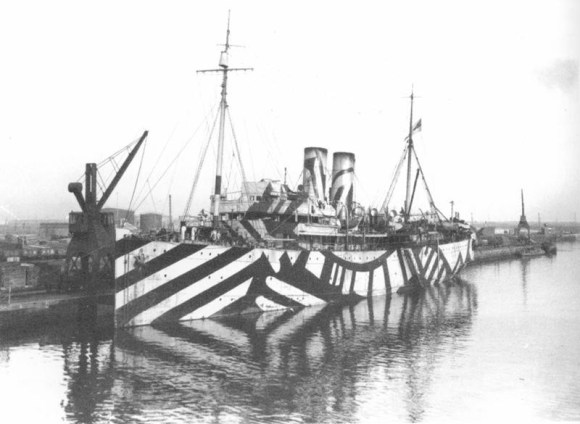

The Aubrietia type of sloop was similar to the Arabis. Only six were ordered in 1916 and one of these, HMS Heather, was built at Grangemouth. They were specifically built to answer the submarine menace and acted as convoy sloops, as did the following Anchusa type. Both Aubrietia and Anchusa types were built with merchant ship profiles. Two out of the 33 Anchusa type sloops that were ordered in 1917 were built by the Greenock & Grangemouth Dockyard Co. These were HMS Marjoram at Greenock and HMS Mistletoe at Grangemouth. They were each 1,290 tons, 250ft by 35ft, with two 4in guns and two 12-pounder guns. The final type of minesweeping sloop was the “24” type. 24 were ordered in 1917, but many were only completed as the war was ending. It continued the trend to larger vessels, at 1,320 tons, 267ft 5in by 35ft. HMS Hibiscus was launched at Greenock in November 1917, and HMS Donovan, HMS Sanfoin and HMS Sir Hugo in 1918. HMS Isinglass was the last minesweeper, launched as late as 5th March 1919 (Appendix 9).

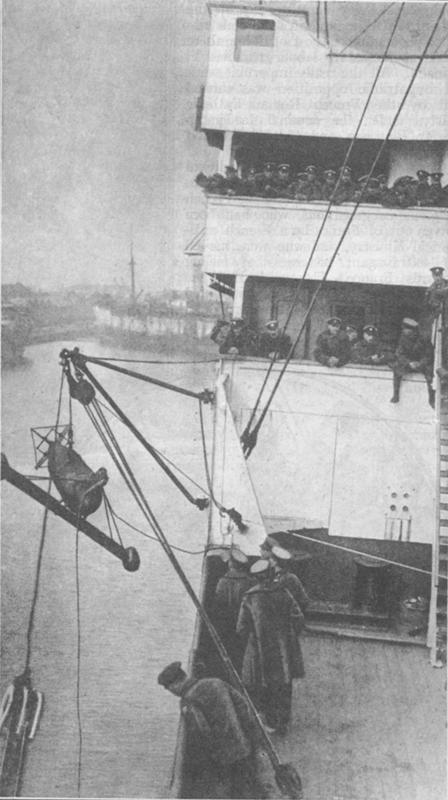

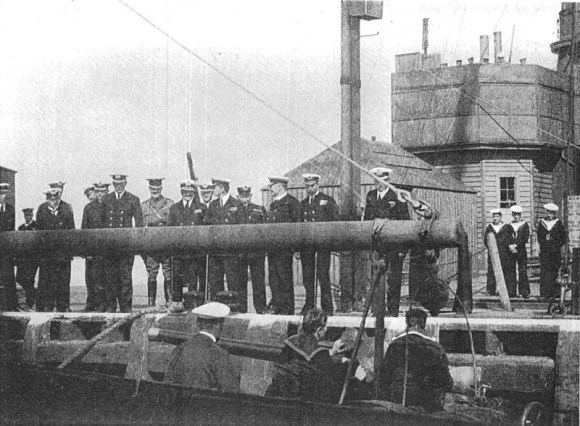

The importance of the work of the Greenock & Grangemouth Dockyard Company to the war effort was acknowledged when the King launched a vessel from the Greenock yard on 17th September 1917 by cutting a rope with a small axe. Dockyard workers from Grangemouth went through to witness the event and played a bowling match against their counterparts there.

The importance of the work was reflected in other ways. It strengthened the hand of the men in wage negotiations, though they did not always get what they expected. At the beginning of the war many of the riveters joined the Forces, leaving the yard depleted just when it received the first Admiralty work. Four squads of apprentice riveters had enlisted and so, in May 1915, the Dockyard Company brought three squads in from Greenock and provided them with accommodation.