An Introduction

Until the 19th century the idea of public parks would have been anachronistic to the inhabitants of central Scotland. They got plenty of physical exercise in their daily lives and childhood was relatively short. There were plenty of open spaces for games and so little traffic that roads were essentially linear playgrounds. The latter is illustrated by the game known as “hengie” or bullets, which involved throwing a stone ball along the public roads over a set course, with the team taking the least number of throws winning. It was very popular but, needless to say, it was banned by one of the many Road Acts as a result of the increasing traffic. This way of life changed as the pace of activity increased and the urban areas grew in size with more and more children attending school for longer and longer. Farmer’s fields in the vicinity of the towns were pressed into service as playgrounds during their fallow spells and by the mid-19th century the civil authorities were paying for the privilege of using them. Each year the burgh officials sought out suitable fields to be used. They were not always available. At the same time the number of organisations concerned about the welfare of the youth mushroomed. Many of these held annual outings and picnics supported by aristocratic sponsors. Estate owners contributed to the enrichment of the lives of the young in these organised parties with Christian charity and opened up their fields and gardens for several days a year. This inspired not only an awe of nature but an appreciation of the vibrancy of huge arrays of flowers in gardens.

The first permanent public park in the Falkirk district was that at Camelon beside the Forth and Clyde Canal and was first leased in 1862. Its purposes were stated to be those of recreation, quoiting and bleaching! The south-facing slope and the presence of a stream made it suitable for the practical function of bleaching cloth which could then be dried on the hedges. It was to be 1929 before the land was transferred into the ownership of the local authority.

Falkirk’s first permanent public park was Princes Park on the Slamannan Road which was created in 1893. For years the Town Council had leased different fields adjacent to the small town on an ad hoc basis but with the changing agricultural practices and the growth of the town these were becoming more difficult to secure. The location of the new park, up a steep hill some distance away from the town, was far from ideal, but the Council already owned the land as a result of the division of the common muir in 1807. It was to be a cheap affair. All that was needed was a field to provide a safe place for the children to play and exercise and for the adults to listen to live music provided by bands. A trotting track was laid down at little expense – the ash required for it and its carriage being provided by the North British Railway. The principal costs were those of a gate and a wooden platform for the bands.

The location of Prince’s Park was so inconvenient that in 1895 a second park was acquired at Thornbank to the east of the town. Much of the money required to purchase it came from public subscriptions. Its chief feature was also an ash perimeter track which had already been installed by a local running club. Opening Falkirk’s second park, Provost Griffith said that it had been provided for the people of the town so that

“they should have breathing spaces – that they should provide lungs for a community such as Falkirk was, so that they might have a healthier people” (Falkirk Herald 10 Aug 1895).

It was named “Victoria Park,” with the Queen’s permission.

At Bo’ness, a public park was provided at the instigation of a well-meaning local landowner for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1897. Henry M Cadell was in the process of forming a new “garden” suburb and the steep ground at the Braes was not suitable for housing. It was, however, ideal for a public park as it provided sheltered views across the Forth and contained a public well. He had terrace paths made in the hillside and planted trees. The trees were a major feature of the layout and were part of a trend for all of the parks in the area. They could be used to create avenues and vistas, or as individual specimen trees to commemorate special occasions such as the opening of the parks, or coronations, or even the cessation of hostilities after a prolonged war. And they were useful for shelter.

Swings, chutes (slides) and maypoles were soon provided but the lack of formal ornamentation was deliberate and not simply to save money, as can be observed in the following statement referring to a park in Bo’ness;

“The proposals mooted for setting-out and embellishment of the Glebe Park savoured too much of the front garden plot. What is wanted is an open space, more than gentleman’s lawn or a park decorated with a profusion of flowers and shrubs. It is to be hoped the Commissioners will see to it that nothing is done to make the Glebe other than a park for recreation and a place suited for a quiet rest of a summer evening...” (Linlithgow Gazette 17 March 1900, 4).

Inevitably there was much back sliding – and not just on the chutes. The public came to demand better laid out parks with formal paths and flower beds. The landowners who released the land to them demanded fencing to stop the boisterous youths from entering their adjacent fields or works and in the case of Dawson Park this was provided by the Carron Company. Often the fencing at the main gate was more ornamental than elsewhere, and the gates could be quite elaborate.

The 1930s witnessed a great explosion in the provision of recreational facilities for the public in the new suburbs. Financial aid for playground equipment came from the Miners’ Welfare Scheme and with its help the zenith was reached on the evening of 14 August 1934 when some three playing fields were officially opened by the Eastern No 2 District Council at Wallacestone, California and Brightons Quarry. Each had two sets of swings, a plank swing, a chute, and a joy wheel. The very following year that council took over the supervision of playing fields at Reddingmuirhead and Glen Village. The ground at Reddingmuirhead had been purchased by the Redding Miners’ Welfare using the central fund, whilst that at Glen Village had been bought by the Callendar Miners’ Welfare.

Public parks played an important role in the war effort against Germany. During the First World War many had been utilised to provide land for the provision of allotments in an effort to grow more food and this was repeated in 1940. This war was different because now the enemy bombers could reach all parts of the kingdom. In October 1939 local people turned out in large numbers to dig slit trenches in the parks to act as public air raid shelters. Some were adopted by the ARP authorities and were provided with shoring, but most were dangerous and had to be filled in. Surface shelters were built in their place and after the war these were converted into stores, shelters for old men and changing rooms. A decontamination centre to treat the victims of poisonous gas was erected at the Lido and also became changing rooms for the adjacent sports fields. At Dollar Park a control centre was converted into a children’s nursery; and at Bellsmeadow another decontamination centre became a health clinic. The elevated location of some of the parks made them suitable for the positioning of observation posts and the central location of others for machine gun posts. They could also be used for training local volunteers in shooting and the Home Guard often held exercises in the parks.

It was, however, for their social uses during the war that the parks are best remembered. The Home Guard held fundraising events and parades. The ARP held demonstrations and displays of its equipment; as did the armed services. National fundraising campaigns such as Salute the Soldier, War Weapons Week, Wings for Victory, all had events in parks. Drumhead services needed the space that only the parks could provide. Along with the Dig for Victory campaign there were others with parks at the centre, such as Holidays at Home. By holidaying in the parks the trains and roads were freed up and consumables conserved. Live music was provided by bands, many of them military. Recorded music could be used for dancing to and dance floors were constructed. That at Dollar Park was of wood, but the one at Zetland Park was made of asbestos sheets. Shows were promoted and even circuses continued. Sheepdog trials became surprisingly popular. There was Punch and Judy for the children.

As well as the displays of wartime equipment there were exhibitions of all sorts. Flower and vegetable shows returned. Beauty competitions were arranged for babies and young women. Football, hockey, tennis, table tennis, draughts, and other games were catered for.

George V took a personal interest in the work of the National Playing Fields Association and so after he died it was decided to raise a fund to create a memorial to him in the form of a network of playing fields. By providing grants to cover some of the costs of creating such parks it was hoped that it would act as a catalyst to local communities in the provision of new recreation grounds. The scheme was established in 1938 and fundraising began; at the same time proposals were requested. These had to be worked up schemes rather than simply aspirational. In the autumn of 1939 the council that covered Stenhousemuir considered applying but the advent of war delayed any action. The scheme sprang back into action after the war and by 31 December 1950 the total number of approved schemes was 505, of which 379 were in England, 86 in Scotland, 32 in Wales and 8 in Northern Ireland. Five were in Stirlingshire. The Foundation’s grants to these schemes totalled £547,674. All of the parks taking part in the scheme were to display heraldic panels, the insignia of a Memorial Field, on their entrance gates. The first to be completed in the Falkirk area was Crownest Park in 1953. Westquarter and Redding followed in 1955 and 1956.

The following decades saw a trend to the development of country parks. Country Parks were normally centred on old estates and were recognised by the Countryside Commission. They had rangers to guide the public and organise events and some 40 or so were created in Scotland. Falkirk District Council acquired Muiravonside Estate and this has been developed over the years. It complemented existing estate parks at Callendar, Kinneil and South Bantaskine.

In recent years there has also been a trend to establish “Friends” groups to help with the promotion and maintenance of the parks. That at Dollar Park is one of the most active and was involved with the consolidation of the doocot there, the restoration of the floral clock, and the enlargement of the war memorial.

Name

There are two names for public parks in Scotland which stand out as being the most common – Glebe Park and Victoria Park. Both are self-evident. By the end of the nineteenth century, just as sites for public parks were being sought, the established church was disposing of the glebes which the ministers had used to graze their animals and to provide additional income. As this was essentially a supplement to their salary the minsters had to agree to the sale. At the same time Queen Victoria was reaching the end of her monumentally long reign and in 1897 many diamond jubilee celebrations were commemorated by the opening of a public park. The Queen graciously permitted her name to be attached to many. There are also two parks called Prince’s Park in the area – one on the Slamannan Road looking down onto the town of Falkirk (dating to 1893), and one at California (dating to 1935). The district also has two Blinkbonny Parks – one in Falkirk and one in Slamannan. The name is a Scottish compound which implies a place with a good view – the Scottish equivalent to Bellevue. Both parks enjoy such a facility and in each case the word is taken from existing place names.

In the twentieth century private donors stepped forward and their names were attached to the land that they gifted to the public. Hence Anderson Park and James Anderson Park, Calder Park, William Dawson Park, Dollar Park, Duncan Stewart Park and so on. Carron Company was responsible for Burder Park and Maclaren Memorial Park.

Bonnybridge Gardens occupy the old site of the old Central Railway Station and so could have been called Central Park. This linear park runs parallel to Wellpark Terrace which was named long before the station closed; and so Well Park was another possibility.

At Burder Park and McLaren Memorial Park the name was included in an iron arch over the main gates. At Victoria Park in Falkirk it was incorporated into the gates themselves. Most of the parks have a separate sign at their entrances bearing the name, along with a notice board for upcoming events.

Paddling Pools and Water Features

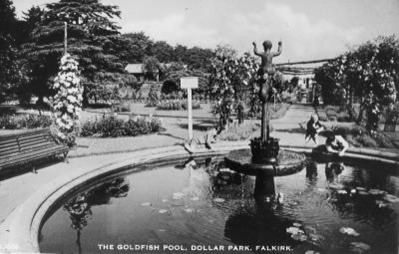

When Dollar Park was handed over to the Falkirk Town Council in 1922 it already contained a gravity fed “jet d’eau” which had been created by its owner, James Russel, in 1853. This was located in the centre of a 6.6m diameter bowl. Shortly afterwards the Gentleman Fountain in the town centre was dismantled and the eagle finial was placed in the centre of this pond, and was later replaced by the magnificent statue to Peace from south Bantaskine created by Sir Alfred Hardiman in 1918. The power of the water jet had been diminished but the lily pond with its fish was a great attraction. Sadly, it is now infilled and serves as a flower bed.

In the Falkirk area the first of the public paddling pools was provided in 1931 in Zetland Park and by any standards it was enormous. Such ponds were used for sailing model boats as well as paddling. Another large pond was used by the children of Stenhousemuir in Crownest Park and was much appreciated when it first opened in the scorching summer of 1939. In some ways this was an accidental pond as the area had been a derelict sand quarry in which pools had formed naturally. Ironically the pool and its sandy surroundings became known as “The Lido,” a popular name in the 1930s for a public outdoor swimming pool and surrounding facilities, taken from an Italian word for a fine beach.

Almost every park had a drinking fountain and some an ornamental fountain. The drinking fountains varied from the large elaborate cast iron McPherson Fountain in Zetland Park and the Dalton china Jubilee Fountain at Victoria Park in Bo’ness to the simple robust stand pipes of the rural playing fields. These allowed children to spend longer periods playing safely in the parks at a time when parental supervision was limited. Sadly, concerns over hygiene have meant that most no longer deliver potable water. The installation of a bottle re-filling point at Callendar Park by Scottish Water around 2012 was a welcome exception. The recently restored McPherson Fountain compares well with such contemporary civic structures throughout the country and is a wonderful monument to the iron industry.

Large ponds may be found at Kinneil and Callendar. The latter was part of the late 18th century designed landscape for the mansion when there was a movement to create romantic rural settings. The former started life as a reservoir for the nearby distillery but is now a tranquil haven.

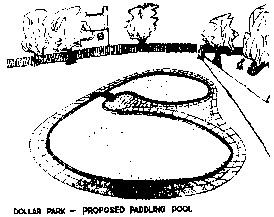

The 1950s was the main period for paddling pools and during the hot summers they were a great boon. One of the last pools to be installed was that at Dollar Park which was funded by the Falkirk Round Table in 1963. Most had been round or square, but this one was kidney-shaped and even had a bridge. However, the teenage youths soon got to work on these recreational facilities and the cost of maintaining them rose to prohibitive levels. The damage caused by vandalism was on many levels. Throwing stones in to muddy the water was one mild form; using broken glass was more dangerous and resulted in many of the younger children wearing jeelies – plastic sandals. Other pollutants were used and physical damage to the walls occurred. Attacking the source of the water and adjusting water levels was also dangerous. Inevitably the purity of the water declined and one by one the ponds were abandoned.

| PARK | DATE OPENED | GRID REFERENCE | SHAPE & SIZE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zetland Park | 1931 | NS 9300 8134 | Pond – large |

| Crownest Park | 1939 | NS 8681 8273 | Pond – large |

| Glebe Park, Denny | 1950 | NS 8117 8268 | square – medium |

| Allan Crescent | 1950 | NS 8101 8348 | square – medium |

| Victoria Park, Falkirk | 1950 | NS 8968 8046 | circular – large |

| Camelon Park | 1952 | NS 8732 8026 | circular – medium/large |

| Dalgrain Park | c1955 | NS 9119 8206 | square – medium |

| Anderson Park, Denny | 1950s | NS 8119 8202 | square – medium |

| Dollar Park | 1963 | NS 8805 8034 | kidney-shaped – large |

For the same safety reasons the authorities preferred to cover over streams that flowed through the public parks. Here the children could paddle or guddle for fish. At Dalgrain Park a drainage ditch represented an old line of the River Carron. As it lay in a low part of the field and so was prone to flooding it was placed in a pipe and the ground level significantly raised. In many cases the cost of culverting the burns was too high and thankfully many, such as that in Camelon, survived.

Zetland Park was also prone to flooding and so the artificial course of the adjacent Grange Burn was heavily embanked and this was utilised for a raised causeway with an avenue of trees which formed part of the perimeter perambulation of the park. Pedestrian bridges over the burn added to the character of the setting. A small park in Slamannan along the north side of the Culloch Burn actually features a waterfall known as the Rumlie because of the rumbling sound. Waterfalls can also be seen on the River Avon at Muiravonside where there is a stunningly beautiful riverside walk in the glen. Unfortunately the waterfall or cascade at Callendar Park is no longer active but the dam and observation bridge are still present.

Zetland Park was the only one in the Falkirk area with a swimming pool, though elsewhere adjacent streams and canals were pressed into service. It was built in 1924 and was well used. It survived until the opening of a new indoor pool in 1971. A swimming pool had been mooted for Dollar Park in the 1930s but was never brought to fruition.

One unusual park feature was the skating pond at Victoria Park in Falkirk which was installed in late 1895. A small bank of clay puddle, 1ft 10ins tall at its highest point, was inserted into the centre of the running track to enclose an area of almost 4 acres and this could be filled with water from a specially laid pipe. In heavy frost the sheet of water froze and provided a safe skating surface for the local children as well as a convenient curling surface for the adults. It was paid for by Provost Weir. The pond was flooded in mid-November each year and usually kept in this state until late February when it was drained and the grass allowed to grow again. The skating pond ceased to function probably as a result of global warming. The shallow paddling pool in Zetland Park occasionally froze, much to the delight of opportunistic skaters. The modern extension to Callendar Loch has slowly silted up and is now so shallow that it too freezes and pupils from the nearby schools have to be rescued from time to time.

Bandstands

Band music in parks was particularly favoured in the period 1880-1920 and was revived as part of the Holidays at Home campaign during the Second World War.

Prince’s Park and Victoria Park in Falkirk, had wooden platforms for the bands to play on. Rather confusingly these are sometimes referred to as “bandstands” in the contemporary archives. An open raised dais made of concrete or asphalt might also be so described.

| PARK | DATE | GRID REFERENCE | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glebe Park, Bo’ness | 1901 | NS 9983 8142 | Walter Macfarlane & Co. Still present. |

| Dollar Park | 1924 | NS 8794 8029 | Home made. Demolished 1960s. Rebuilt 2012. |

| Carronbank Park | c1905 | NS 8099 8306 | Home made wooden structure. Demolished 1915. |

| Zetland Park | 1925 | NS 9295 8140 | Demolished 1973. |

| Victoria Park, Bo’ness | 1925 | NT 0077 8138 | Home-made wooden platform. |

A wooden stage built into the walled garden at Dollar Park in the 1920s doubled as a bandstand. The enclosure provided a sheltered area in which to listen to the bands or plays. Today this has been revived by the construction in 2012 of a raised platform which used the cast iron columns removed from Grahamston Railway Station.

The iconic type of enclosed ornate cast iron bandstand made by Walter MacFarlane was to be found in the Glebe Park in Bo’ness and Zetland Park in Grangemouth. The former survives and is about to be restored but the latter was removed in the 1970s.

Other Features

Modern works of art were also inserted into Callendar Park and their silver metallic finishes provide a deliberate contrast to the antique designed landscape. One, at the east of the Loch, takes the form of a pie-chart. In 2015 a new sculpture walk was installed in the field between the car park and the visitor centre at Muiravonside and features elements of nature.

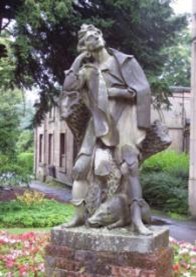

In common with the parks surrounding country houses, several of Falkirk’s parks contained items of sculpture. The statue of the Prodigal Son in Dollar Park was a relic of a previous owner, James Russel, who bought it in 1854. It was executed by Robert Forrest, who also sculpted the equestrian statue of Wellington in Newmarket Street. However, the two Chinese marble Peking lions there were only put in place a few years after it became a public park. They were acquired by Robert Dollar on one of his trips to Peking and were placed astride the entrance by the Parks department in September 1928. A third sculpture at Dollar Park is in the form of a bronze bust of Sheila McKechnie OBE, a Scottish trade unionist, housing campaigner and consumer activist, and dates to 2006. The final piece in this park is of Peter Pan and was installed in memory of the unnamed babies who died in hospitals.

At the entrance to Kinneil Park is a massive reproduction of a first century Roman harness fitting which was found during the excavation of the fortlet there. This park also has several log benches with chainsaw sculpted terminals and a heritage trail featuring totem poles is due to open in 2025. Similar carvings may be found in the children’s playground at Callendar Park where the stumps of trees were carved in situ and, in keeping with that of the enclosure, have a Roman theme.

Symbolic sculptures in the form of war memorials also appear in our parks. In some cases, such as at Dollar Park, this is because the land was already in public ownership and so reduced the cost of erection. Here the location was also aptly adjacent to one of the main entrances into the town. The monument is in the shape of a cenotaph – an empty tomb. More common were the obelisks and variants upon them. The tall monument at Bo’ness overlooking the Forth was placed in a detached part of the Glebe Park – cut off by the construction of Stewart Avenue. At Bonnybridge, on the other hand, the park was largely created to take the polished pink granite obelisk. The latest, as recently as 2022, stands within Dawson Park.

Other connections with war could also be found in the parks. An 18-pounder Carron-made cannon was on view in Victoria Park in Bo’ness from 1902 onwards and became affectionately known as “Old Harry.” It was fired to salute royal events and to welcome in the New Year, but was scrapped as part of the war effort in 1940. Kinneil Park also had a couple of field guns.

The 1298 Battle of Falkirk was commemorated at the Victoria Park in Falkirk by a decorative drinking fountain sponsored by Robert Dollar in 1912. It is topped by a lion and in the last few years its setting has been much enhanced. More simple in form was the cairn erected in Callendar Park in 2007 to the memory of William Wallace and the men who died at that battle. The earth mound to the north-west of Callendar House may commemorate the siege of that castle in 1651 by Oliver Cromwell. It was part of the late 18th century designed landscape.

Features from the old aristocratic estates survive within Callander Park and may also be found at Muriavonside Park, Dollar Park, Kinningars Park, Kinneil Park, and South Bantaskine Park. These include doocots, summer houses, lodges, arboretums, family graveyards and walled gardens. Other features such as kennels, observatories, quarries, and sundials are either hidden from view or lost. They may be considered as archaeological sites along with a hill fort and a strong castle in Callendar Park, a monastic grange in Zetland Park, an Iron Age hut in Rannoch Park, and Roman burials in Camelon New Park.

The pets’ corners in Dollar Park and Kinneil Park are also in the past, though the “farm” at Muiravonside continues strong. The Dollar Park zoo was installed in the early 1930s and included rabbits, guinea pigs, a squirrel, and even a monkey. The aviary housed an owl, a white cockatoo, pheasants, budgerigars, a magpie and a hawk.

Sporting facilities included tennis courts, putting greens, table tennis tables, bowling greens, football and rugby pitches, and so on. One essential was a suitably equipped playground for children.

These possessed chutes (slides), swings, see-saws, maypoles, plank swings, and joy wheels. In more recent years we have climbing frames, flying foxes, skate boarding ramps, and MUGA pitches. To allow the guardians to monitor young children these are often set in fenced enclosures within the parks.

The flower beds which require much care and attention have been reduced to a rump. In the 1920s most parks had a propagating house or greenhouse to raise plants but these were easy targets for the vandals, as were the beds. Latterly these were replaced by a central nursery in the walled garden at Kinneil but in 2019 even this was closed. The floral clock at Dollar Park, absent for many years, was recently revived by the Friends of that park. The arboretum there is robust and continues to delight. One recent trend has seen a considerable improvement in the path networks. These have been surfaced with asphalt and provided with ground level solar lighting, making them safer to use in the long winter nights. In the long winter evenings they look like landing strips and are much used for regular exercise and by dog walkers.

Topography

Many of the public parks were on slopes and whilst at first sight this made them inconvenient for ball games, it made them ideal for sledging and Easter egg rolling. They also provided excellent viewing points, usually northwards to the Forth with the Ochils beyond. Princes Park has long had a view indicator.

.

Where football pitches were required this often involved a lot of terracing and the movement of hundreds of tons of earth. Quite a few pitches were placed on levelled industrial bings – such as that for the Anchor Brickworks in Dunipace; at Broomhill in Bonnybridge; and for the Policy Bing at Lionthorn. Two tiered parks ended up with a High Park and a Low Park – examples at Tygetshuagh and Laurieston. At Victoria Park in Falkirk a natural scarped bank marked the edge of the carse and this was exaggerated and retained. A running track was placed on the lower flatter ground to the east. This also proved ideal for the large skating pond. The upper park was used for monuments, formal gardens and the community centre.

Opening Times

Right up until the Second World War most parks were kept locked on Sundays and playing football in them on that day resulted in many a court appearance for the young boys involved. The parks were fenced about and the by-laws created by the local councils stipulated that they should be closed from mid-evening until early morning. The reason for this was more to do with control than public morality. Naturally, the policy failed as it resulted in much vandalism as the children did their utmost to break into the secure compounds. The financial cost of replacing segments of the cast iron railings at Dawson Park was almost crippling. Whilst the removal of the railings of parks in the Second World War did little to improve their appearance, it did at least open them up. Exemptions with regard to the removal of the railings were only given if they were considered to be of particular artistic merit or they were required for safety. This resulted in the incongruous sight of heavy iron gates with stubs of railings attached set along an otherwise open boundary.

Inventory

Today we are blessed with a large number of public parks, recreation grounds, playing fields and public open spaces. These categories overlap. The parks and open spaces in the Falkirk district cover over 24 square kilometres spread out on 632 individual sites. Only a select few are included here but it is hoped that they reflect the variety available. These are the spaces with some formal ornamentation, even if it only takes the form of garden benches.

The following parks are covered in this inventory:

| AREA | PARK | SIZE (Acres) | DATE ESTABLISHED |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bo’ness | Calder (& Castleloan) | 5.5 increased to 7.4 | 1927 |

| Bo’ness | Douglas (Bankhead) | 14.0 decreased to 12.4 | 1928 |

| Bo’ness | Glebe | 5 decreased to 4.0 | 1899 |

| Bo’ness | Kinglass (Chance) | 1.1 increased to 2.0 | 1910 |

| Bo’ness | *Kinneil | 1923 | |

| Bo’ness | Kinningars | 14.6 | c 1970 |

| Bo’ness | Victoria | 9.5 decreased to 7.2 | 1897 |

| Bonnybridge | Allandale | ||

| Bonnybridge | Anderson | 6 | 1920 |

| Bonnybridge | Bonnybridge Gardens | 1970s | |

| Bonnybridge | Bonnybridge Memorial | 1920 | |

| Bonnybridge | Duncan Stewart | 7 | 1935 |

| Bonnybridge | High Bonnybridge (Loch or Broomhill) | 5.6 acres | 1951 |

| Bonnybridge | Hollandbush | ||

| Bonnybridge | Roman Road | 1.3 | 1953 |

| Camelon | Camelon | 7.7 | 1862 |

| Camelon | Camelon New | 13.0 | 1938 |

| Camelon | Stirling Rd | 1970s | |

| Denny | Allan Crescent | 1950s | |

| Denny | Anderson | 1950s | |

| Denny | Carronbank | 5.2 | c1910 |

| Denny | Herbertshire Castle | 17.8 | 1950s |

| Denny | James Anderson | 6 | 1929 |

| Denny | Tygetshaugh | 1950s | |

| Falkirk | Bellsmeadow | ? + 7.5 decreased to 15.1 | 1949 |

| Falkirk | Blinkbonny | 6.5 | 1910 |

| Falkirk | Dawson | 12 | 1907 |

| Falkirk | *Dollar | 10.9 | 1923 |

| Falkirk | Laurieston (Zetland) | 5.2 | 1880s, ext 1932 |

| Falkirk | Princes | 8.3 decreased to 7.9 | 1893 |

| Falkirk | *Victoria | 16.2 | 1895 |

| Falkirk | Westquarter | 1955 | |

| Grangemouth | Dalgrain | 1950 | |

| Grangemouth | Inchyra | 16.0 increased to 30.9 | 1960s |

| Grangemouth | Rannoch | 1970s | |

| Grangemouth | *Zetland | 8.5 increased to 45.8 | 1882 |

| Larbert | Bothkennar | ||

| Larbert | Burder | 1937 | |

| Larbert | Crownest | Decreased to 6.5 | 1938 |

| Larbert | MacLaren Memorial | 3.3 | 1927 |

| Larbert | Russell (Greengate) | 1980s | |

| Larbert | Stewartfield | 1.8 | 1920s |

| Polmont | Gray-Buchanan | 1974 | |

| Polmont | King George V | 1956 | |

| Polmont | Laurie | 1934 | |

| Polmont | *Muiravonside | 170 | 1978 |

| Polmont | Polmont | 1970s | |

| Slamannan | Blinkbonny | 7.2 | 1956 |

| Slamannan | Rumlie | 2.2 | 1964 |

| Slamannan | Slamannan | 1936 |

Those in *bold had been surveyed before the present work was undertaken.

BO’NESS

- Calder Park & Castleloan Park

- Douglas Park (Bankhead)

- Glebe Park, Bo’ness

- Kinglass Park (Chance Park)

- Kinneil Park

- Kinningars Park

- Victoria Park

BONNYBRIDGE

- Allandale

- Anderson Park, Bonnybridge

- Bonnybridge Gardens

- Bonnybridge Memorial Park

- Duncan Stewart Park

- High Bonnybridge & Loch Parks

- Hollandbush Park

- Roman Road Park

CAMELON

DENNY

- Allan Crescent Playground

- Anderson Park, Denny

- Carronbank Park

- Glebe Park, Denny

- Herbertshire Castle Park (Gala Park)

- James Anderson Park

- Tygetshaugh Park

FALKIRK

- Bellsmeadow

- Blinkbonny Park

- Callander Park

- Dawson Park

- Dollar Park

- Laurieston Park

- Princes Park

- South Bantaskine Park

- Victoria Park

- Westquarter Park

GRANGEMOUTH

LARBERT

- Bothkennar Park

- Burder Park

- Crownest Park

- Maclaren Memorial Park

- Russell (Greengate) Park

- Stewartfield Park

MUIRAVONSIDE Country Park

POLMONT

- Gray-Buchanan Park

- King George V Park

- Laurie Park

- Polmont Park

- Princes Park, California

- Wallacestone Park

SLAMANNAN

- Blinkbonnie Park, Slamannan

- Rumlie Park

- Slamannan Public Park

Bibliography

| Gillies, A. | 2018 | Denny and Dunipace in Words and Pictures. |

| Waugh, J. | 1977 | Slamannan Parish through the Changing Years |