Early education in Scotland had focused on religious knowledge, Latin and Greek with a basic understanding of English and mathematics. By the late 19th century practical subjects such as navigation or land surveying were taught at a number of private schools. Falkirk Science and Art School arose in 1878 out of the need to teach skills that could be put to use in the emerging industries. Parallel to this was the work of the Falkirk Ragged School, which sought to make the poor street urchins useful to society by fitting them for work. This school evolved into the Industrial School and in many ways this was latterly the trades’ school for youngsters that had been through the court system.

With the development of mass education and an older school leaving age something new was needed and the Falkirk Herald of 10 September 1932 neatly sums up the ethos and spirit of the age:

“Modern education is developing on broader and more comprehensive lines as year succeeds year. The old days of the three-Rs have long since vanished. Our schools are crowded, our universities are unable to cope with the students presenting themselves for degrees. But it has been left to Falkirk to point the way to a newer form of education, which is now ranking in honourable place alongside arts, medicine, and the other faculties. Technical knowledge has too long been neglected, although this is surely an age of super technicality. The opening of the new Falkirk Technology School on Monday marks the commencement of a fresh era in the pioneering of knowledge. A sum of approximately £80,000 has been spent in building and opening this school, and the Education Committee, which after all has its finger directly on the pulse of contemporary requirements, believes that the money has been well spent. If schools like this are opened all over the country, there is going to be evolved a completely new type of artisan, the educated workman who takes a pride in what his hand produces, just as a doctor, a school teacher, or a minister each find true satisfaction in exploring to the full the fruits of their learning. To some people it may seem strange that an elaborate model foundry should have been incorporated into the new school at a time when the blackest of clouds overhangs the whole light castings industry. But this at least shows the optimistic and long-sighted policy of the Education Committee in this respect. There can be no excuse now for a slip-shod generation of technical workers growing up in Falkirk and district. No expense has been spared to ensure that thoroughness will be the keynote of every item on the curriculum of the new school. The stage is set for one of the most momentous experiments in the history of Scottish education, and it is flattering and gratifying to reflect that the town of Falkirk has been selected for the launching of the new scheme. At the present moment one thousand children have entered upon a new educational life within the walls of Falkirk technical School. The onus is upon them to show their appreciation of the Education Committee’s effort by taking full and intelligent advantage of the incomparable opportunities which stretch before them.”

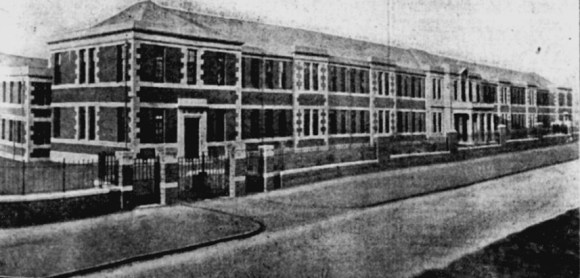

This fanfare was not all bluster for the Falkirk Technical School opened its doors to students on 5 September 1932 with just under a thousand pupils. The school was designed by A N Malcolm, the Education Committee of Stirling Council’s own architect, and his team, and was three years in the planning. Unusually, a consultant engineer was hired to fit out the workshops. In all it cost a little over £80,000.

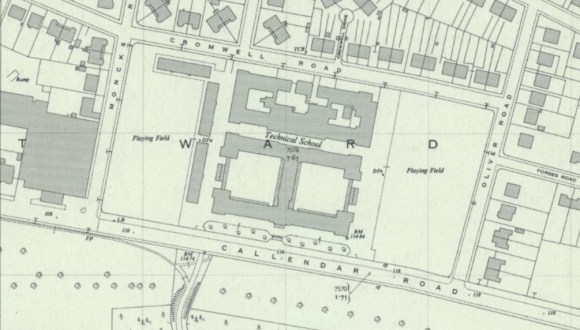

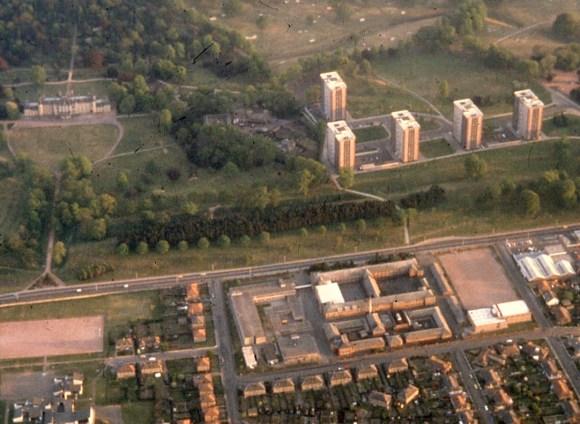

The extensive feu, 8 acres in size, was obtained from Forbes of Callendar and lay on the north side of Callendar Road opposite to Callendar Park. Its size meant that large playing fields could be provided to either side and the buildings were laid out in a spacious manner which contributed to its “palatial” feel. It allowed ample provision for future extension.

There were two handsome blocks of buildings faced with Huncoat brick, an engineering brick with a bright red colour, framed by the use of cast stone of a red hue for string courses, quoins, the wallhead and plinth courses. The roofing was of Consiton light-green slates. The long main façade faced Laurieston Road. At its centre the broad entrance porch projected on Doric columns supporting a classical entablature with triglyphs carrying a balcony. Central to the porch, on the first floor, engaged Ionic columns supported an open-base triangular pediment containing the County Council’s emblem in reformed stone/concrete. Sprouting from the apex of the pediment the flagpole was also made of concrete. These Neoclassical features gave the building a traditional scholarly feel and the high quality of the internal design continued this ideal.

The pillared inner entrance hall acted as a reception lobby giving access to classrooms to the left and right in the south wings. Straight on from the lobby, the doors gave access to a fine huge assembly hall capable of sitting 500 on folding seats. The hall was aligned north/south and the vastness of the space gave it dignity and the use of a subdued colour of Celotex provided a modern interior. The hall was aligned north/south and the vastness of the space gave it dignity and the use of a subdued colour of Celotex provided a modern interior.

Celotex was an insulation fibreboard which was then fashionable – unfortunately it also contained asbestos. Non-glare flood lighting was seen as novel as were the exceptionally good acoustics. The platform was large so that it could be used not only for presentations at assemblies and public lectures but also as a stage for amateur theatricals and recitals. Two dressing rooms supported this function.

Radiators in every room provided central heating operated on the oil-burning furnace low-pressure hot water system. A central hooter system also operated – worked from a master clock in the janitor’s room, which also controlled every clock in the building – over a dozen of them. The synchronised hooters announced the end of each lesson period or were prolonged for fire alarms.

The entrance hall also gave access to corridors that ran along the north side of the southern wings, turning perpendicularly north at their ends. They then returned along the south side of the northern wings, thus enclosing two quadrangles separated by the assembly hall, flanked by open colonnaded verandas. These large open cloister-like squares were used for dancing demonstrations, drill, and the like. The corridors were broad with large expanses of glass to the open squares and classrooms on the other side. The main block contained 16 classrooms, all of a standard size and design, to accommodate 640 pupils. Each classroom was fitted with a revolving blackboard and a notice board. Each had a coloured Celotex frieze at waist height to create a panel effect. Cloakroom and lavatory accommodation were placed on both floors. Adjacent to the entrance hall were the administrative offices and a library. Above these were the staff rooms which had access to the fronting balcony.

The northern block was mostly of a single tall storey. It contained the domestic science departments and the model foundry. The former housed kitchens and sculleries equipped with coal oven ranges, gas cookers, and electric cookers. Adjacent to these was a laundry room with no fewer than 23 tubs and scrubbing boards, as well as electric and gas irons. Next was a dressmaking section with its battery of sewing machines as well as fitting and designing rooms. Along a passage from the housewifery section was the front door of “Technical House.” This was the name given to a model house closely resembling in its arrangement a Council dwelling. It had two bedrooms, a kitchenette, and a scullery. Incorporated in the house was a “Janus” back-to-back range and a washing boiler. At the time these facilities were considered to be for the girls. The boys were provided with a fully equipped mechanics’ workshop where they could work on motor engines. Further along a tall chimney attached to a taller section of the building betrayed the presence of the foundry with two small cupolas for the smelting of cast-iron, and pot furnaces for the smelting of different metals. This was the plant room which was equipped with sand-mixing plant with Pneulac Royer disintegrator; a double spindle pedestal grinder; a 1 ton fixed cupola; a curved tube manometer; a 400 lbs oil furnace; a 60 lbs oil furnace; double cases core stove; a 1½ tons electric overhead travelling crane with floor control brake; oil storage tanks and a semi-rotary tube oil pump. The adjacent pattern shop contained a circular saw bench; a combined surface planing and thicknessing machine; a 30in band-saw; an8in lathe with gap bed; a high speed recessing and boring machine; a gas glue pot; a hand power trimmer; and dust extracting plant. There was also a tool room with a 30in x 15in self-contained grindstone,a self-contained plane and a moulding iron grinder.

The foundry chemical and microscopical laboratories were planned particularly to afford practical facilities for the chemical analysis of metals, primarily cast iron, under general works laboratory routine. Adjoining the chemical laboratories were: a mechanics’ laboratory, upholstery rooms and commercial rooms replete with many typewriters. Then there was the art section – a large room able to accommodate 80 pupils with a large stock of models.

The north block also housed the refractory, a gymnasium and a swimming pool. The tiled pond was 48ft long by 21ft broad, constructed throughout with reinforced concrete. The depth of water ranged from 3ft to 6ft, and “Holophane” dust proof lamps provided the lighting. Along one side of the pool was a large spectators’ gallery, while in the rear were changing cubicles, foot baths and sprays (showers).

In the school grounds there was also a janitor’s house, together with a number of small outbuildings. The following contractors were employed:

- Builder – R. D. & J. Gardner, Stirling.

- Cast stone – Alexander Walls, Stirling.

- Reinforced concrete and steel work – Kelvin Construction Co Ltd, Glasgow.

- Joiner – A Williamson & Son, Grangemouth.

- Flat roofing – Vulcanite Ltd, Glasgow.

- Steel windows – Critall Manufacturing Co Ltd, Braintree, England.

- Glazier – D. O’May Ltd, Falkirk.

- Slater – John Christie & Son, Falkirk.

- Plumber – Arch. Low & Sons Ltd, Glasgow.

- Plasterer – Milne & Co, Stirling.

- Tile work – Clunas& Co, Edinburgh.

- Heating installation – Taylor & Fraser Ltd, Glasgow.

- Electrical installation – James Scott & Co, Dunfermline.

- Railings and gates – Graham & Morton Ltd, Stirling.

- Painter work – Bonnybridge Co-operative Society.

- Tar Macadam of playgrounds – Stark & Dobbie, Kilsyth.

- Furniture – James D Bennet Ltd, Glasgow; Wilson & Garden Ltd, Kilsyth; A Williamson & Son, Grangemouth; Graham & Morton ltd, Stirling; Alexander Stores Ltd, Falkirk.

- Gymnastic apparatus – D Mellis, Glasgow.

- Linoleum – Gillespie & Main, Falkirk.

- Filtration plant for swimming pond – Pulsometer System, – A Low & Sons Ltd, Glasgow.

Over two evenings during the first week of September 1932 some 7,000 members of the public inspected the new school. They were shown around by the staff of 40 teachers who had not anticipated such a turnout. That week 920 children enrolled.

Falkirk Technical School was conceived as a separate Advanced Division School not simply to cope with the increasing number of secondary pupils in the area, but also to provide additional kinds of courses that were becoming necessary in a heavily industrialised and commercialised district. It was not supposed to be a rival to the Falkirk High School, though inevitably comparisons were drawn. The parents and pupils associated with the High School considered it to be academically superior. Indeed, Falkirk High School also ran commercial classes until 1954 when they were concentrated at the Technical School.

There were few changes to the building over the next 25 years. One minor change was brought about at the request of the Scottish Milk Marketing Board – a milk-bar was installed in the refectory at the end of 1937.

Falkirk Technical School played a prominent role in the area’s organisation of civil defence in the Second World War and its pupils raised large sums of money for war charities. In September 1939 the Education Committee had to respond to the urgent need to provide bomb shelters and black-out provision at is numerous schools. First year pupils did not return to Falkirk Technical School until November that year and in the meantime a contractor was employed to build one underground shelter each week from mid-October to Christmas. These soon flooded!

Morale was maintained by the provision of school holiday camps and most of the pupils from Falkirk Technical School attended a camp in the school at Kippen in groups of thirty or so. Here they also helped in forestry work. Ernest Brown MP, Secretary of State for Scotland, visited Falkirk Technical School on 9 December and was photographed talking to the boys in the wood machine shop.

Given the number of schools involved, black-out blinds were considered to be too expensive and were in short supply. So, it was decided that wood would be bought in bulk, and the wood-work staff at Falkirk Technical School would cut it to size and make the frames which were to be covered with paper. That October the woodwork teachers were busy making a survey of the schools, prioritising those parts used for evening classes. The pupils also lent a hand in filling sandbags at Bell’s Meadow just to the west of the school.

In 1947 Burnbank Foundry on the north bank of the Forth and Clyde Canal was bought by the Stirling Education Committee for use as a Trades School. It cost £7,000 of which £5,000 was contributed by the local iron foundries on the condition that it was known as “The Foundry Trade School.” Slowly this aspect of education was transferred to it. Indeed, the institution at Burnbank was used for other trades such as bricklaying. In preparation for the raising of the school-leaving age three standard Ministry of Works hutments were erected on the west playground at the Falkirk Technical School in 1947 at a cost of around £13,787. It was anticipated that these might be the first of many and so later that year a further 15.4 acres of land at The Pikes (extending from the houses to the east of the school up to the Skew Bridge) was purchased. The following year two dining rooms with sculleries and a boiler house were erected, though they had to be carefully located due to the conditions of the feu contract.

During the war the pupils had helped with forestry work and tattie howking. Lack of labour and machinery meant that the latter continued for some time and in 1950 over 450 of the children volunteered for this work.

The elite status of Falkirk High School was dented by its lack of swimming facilities and the Falkirk Technical School made full use of its opportunities. Its pupils were trained in life-saving swimming exercises and were lauded for the resulting bravery they displayed in real life situations. The school also competed with other schools and held an annual swimming gala. It was 1953 before the pool at the Falkirk Technical School was made available to pupils from other schools.

By 1955 the foundry work had been transferred to Burnbank and so the County Architect drew up plans to convert the model foundry at the school to classroom accommodation at a cost of £11,800. The tall single storey building was made into a two-storey building with two classrooms and a small teaching room on the ground floor and three classrooms on the upper floor.

Over the years the school had become more of a conventional senior secondary one and in February 1955 the Education Committee was told the name “Falkirk Technical School” was against the school. It was suggested that the word Technical should be dropped and the school called “Falkirk Academy.” Clearly this was not going to suit those associated with the High School and the matter was put to one side. However, in 1957 the proposal to erect a technical college in Falkirk led to a review of the name and “Laurieston Road High School” was for a time favoured, but in the end the name picked upon was “Graeme High School” and with it a new era was issued in.

| YEAR ARRIVED | HEADTEACHER | YEAR LEFT | No. PUPILS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | James G Lockhart | 1950 | |

| 1950 | Andrew Steele | 1965 | |

| 1965 | William Kerr Morrison | 1982 |

Graeme High School

The school buildings changed little until after 1970 when a detached large steel-framed extension was added to the west along Oliver Road. This was joined on to the Callendar Road frontage of the older block in the early 1990s to form a new entrance and to provide administrative offices, clad with grey brick.

At the turn of the millennium a replacement school building was erected on the school playing fields to the east, known as the Pikes. It was one of five new private finance initiative (PFI) schools in the Falkirk area – the others being two at Larbert, and one each at the Braes and Bo’ness. They were designed and built by the Parr Partnership and Graeme High School was opened in August 2000 by Donald Dewar, the first Minister of Scotland.

Graeme High School included an L-shaped block for 1,200 pupils, featuring on the south an elongated three-storey teaching block in pale red concrete blockwork and white rendered panels, the upper floor a band of continuous glazing, topped with split-section shallow-pitched metal-clad roofs. A pair of flat-roofed stair towers break up through the eaves to give vertical emphasis. Glazed ship’s prow gables contain further stairways. The entrance, administration, conference facilities and library lie to north.

Today (2022) the school has a teaching staff of 92.9 (including P.E. and music staff shared with our cluster primary schools) with a Support for Pupils complement of 6.

| YEAR ARRIVED | HEADTEACHER | YEAR LEFT | No. PUPILS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kristy Rennie | Present | 1119 |

Sites and Monuments Record

| Callendar Road | SMR 1128 | NS 896 797 |