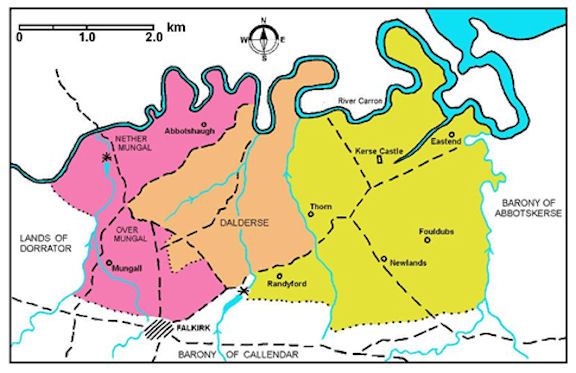

The Barony of West Kerse on the Water of Carron was one of the oldest in the Falkirk district and should not be confused with Abbotskerse or East Kerse, though both of these entities are often abbreviated simply to “Kerse.” The principal residence in West Kerse was Kerse House which later became part of the recreation grounds for ICI and is now the site of an Asda distribution depot. The place name of “Earls Gates” derives from the entrance to the grounds of this house.

The earliest recorded family in possession of the estate is the Stirlings, who were also hereditary sheriffs of Clackmannan. When West Kerse passed, by marriage, to the Menteiths in 1357, so too did the title.

| 1289 | John Stirling |

| John Stirling? (son) | |

| 1357 | Marjory Stirling (daughter) married John Menteith |

| 1382 | William Menteith (son) |

| 1411 | William Menteith (son) |

| c1460 | William (son) |

| 1508 | William (nephew) |

| 1523 | William (son) killed at Pinkie |

| 1549 | Robert Menteith (uncle) |

| 1552 | John Menteith (son) |

| c1565 | William Menteith (son) |

| 1597 | William Menteith (son) |

| 1631 | William Menteith (son) |

| 1631 | sold to William Livingston of Kilsyth |

| 1638 | sold to Thomas Hope of Wester Granton |

| 1643 | Thomas Hope (son) |

| c1648 | Alexander Hope (brother) 1st baronet – 1672 |

| 1674 | Alexander Hope (son) |

| 1719 | Alexander Hope (son) |

| 1749 | Alexander Hope 4th baronet (son) |

| 1747 | sold to Lawrence Dundas |

The early barony of West Kerse included the village or town of “East End” as well as the farms of Thorn, Newlands, Main, Fouldubs, and Randyford. It also included the Lands of Dalderse which some time before 1508 became alienated (Reid 2012, 37 & 38) and Mungal. Around 1500 the lands of Dalgrain also became associated with those of West Kerse. Dalgrain had been in a loop on the north side of the River Carron and was in the lordship of Bothkennar, but when the river changed course leaving the land on the south side it made sense to have it transferred. The River Carron formed the northern boundary of the barony and the Grange Burn its eastern boundary with Abbotskerse. The western boundary with Dalderse was the minor stream known as the Dalderse Pow. Latterly this was little more than a drainage ditch. The southern boundary with Callendar was less well defined and tended to follow the contours at the foot of the hills.

The River Carron dominated the landscape. Here at its lower reaches it was broad and slow moving resulting in numerous meanders and muddy banks. A bed of gravel in the river at Reay’s Ford on the line of the road leading north from Kerse House allowed travellers to cross at low tide. In the winter months this was often impassable and spates were common at that time of the year. The river was teaming with fish and the owners of the barony held the fishing rights which included the authority to erect salmon traps. The meandering nature of the river and the number of pows entering it meant that numerous small boats were held there. The river was also used for trade and Kerse House was ideally located to exploit it. East End was so situated that it had the river on its north-east, the Grange Burn on its east and the Almond Pow on the north. Vessels coming up the river could enter the Grange Burn to unload at the Grange of Abbotskerse, or the Almond Pow at East End. It also appears that the Almond Pow extended up to Kerse House.

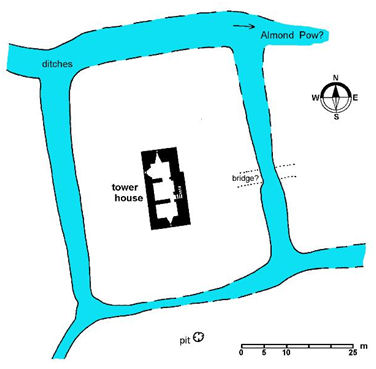

Fleming thought that a tower house was first built at West Kerse by John Menteith some short time previous to 1469. The remains of a tower house were found during an archaeological excavation by Headland Archaeology in 2012 and are consistent with such a date. It is first mentioned in a charter of 1508, by which time we can assume it had been in existence for several years.

The tower house was aligned almost north/south and was rectangular with a slight intake at its north-east corner. It measured 17.6m by 10.8m over gable walls 2m thick. These were of dressed sandstone with a rubble core and had foundations 0.8m deep. Narrow slot apertures with chamfered interior splays occurred in the south, west and north walls. The ground floor contained three rooms, which presumably had vaults aligned west/east. A neatly moulded narrow doorway in the east wall, later blocked, may have led to a stairway built into the thickness of the wall. The excavators identified an external doorway at the shallow re-entrant angle, though the roughness of the dressing of the jamb suggests that this was a later insertion. Given the damp nature of the ground here it is probable that the main entrance was on the first floor.

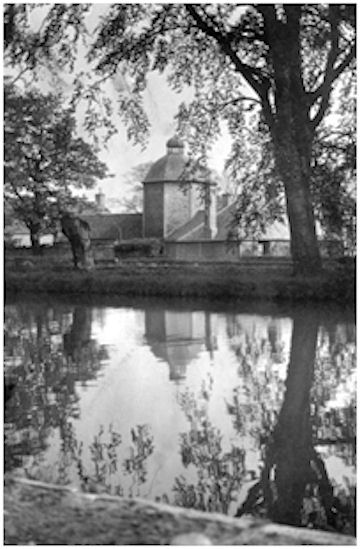

Beyond the confines of the building little stratigraphy remained. Some deep features were found and this included a series of interconnected ditches with steep sides and flat bases set on the same alignment as the tower. The central location of the latter suggests that they were part of the same construction scheme. They may have been dug to act as drainage, keeping the area of the tower dry, but in this part of the world any open ditch soon fills with water and they would have looked like a moat. The ditches varied in depth from 1m to 2.3m. That to the north was 6m wide – wide enough to have taken a boat. These water channels accumulated water-borne silt at their bases over many decades. The water was clearly slow moving and this is confirmed by the presence of celery-leaved buttercup. From the base of the west ditch a soil sample included fragments of moss, insect fragments and pupae, marine shell (eg mussel), fish bone, cinder, land snails, coal and fruit stones. The northern channel seems to have been cleaned out occasionally, and here the fine black silt was less apparent. It was filled by brown silt with wood inclusions. Bottle glass dating between 1750 and 1770 indicates the final period for its infilling. Just beyond this northern ditch the land slopes down by almost 1m and this helps to account for the location of the house. A slight kink in the eastern ditch may indicate the access point, though it may also have been caused by erosion.

The palaeoenvironmental assessment of material from the basal fills of the ditches indicates that the medieval landscape was characterised as open wet pasture with occasional trees. The presence of waste (and possibly faecal) material shows that the ditches were receiving effluent from the house.

The Royal charter of 1508 formalising the accession of William Menteith to the lands and barony of West Kerse gives the following details:

“The lands and barony of West Kerse, both in property and tenandry, specifically – the lands of West Kerse with the tower and fortalice, manor, garden, orchard, fishing of yairs and all other fishing that pertains thereto both in salt water and fresh water, the lands of Ochiltree [Ayrshire] with the mill thereof, lands of Pardovan [West Lothian] with the mill thereof, land of Mungal and Randyford,..”

(Reid 2012, 16).

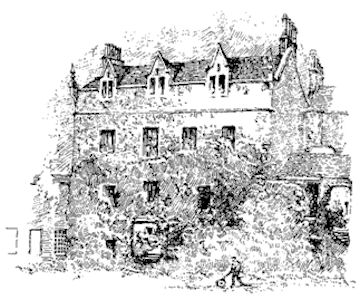

That it was a tower house is confirmed by Timothy Pont’s depiction of ‘Cars Castell’ on his map of 1560. This shows a plain four-storey tower set in a wooded enclosure or park. At the foot of the tower is an outer work which may represent a court of buildings. Fleming’s drawing of the west front of this building shows a rectangular corbelled turret in the centre at ground floor level. This is precisely the place where the wall was later taken down and a staircase inserted. The turret, being only a single storey high, looks a little incongruous and it is possible that it was the base of a much taller one containing a spiral stair for the upper floors, subsequently truncated.

The Menteiths seem to have been quite a belligerent family at feud with other local landowning families, including those related by marriage. The security of the setting of Kerse Castle must have been comforting in such troublesome times. Occasionally this fighting spirit was put to the good of the nation and in 1523 William Menteith was killed at the Battle of Pinkie.

After almost 300 years in the ownership of the Menteith family the barony was sold to pay off debts in 1631. The new owner was William Livingston of Kilsyth whose fortune was in the ascendency. He did not, however, keep it for long and in 1638 he sold it on to Thomas Hope of Wester Granton. Lord Thomas Hope had led a successful career in the legal profession. He was very active in the affairs of state and from 1641 to 1643 he was Justiciar General of Scotland.

Fleming, on the basis of a coat-of-arms on a sundial at West Kerse, attributes Thomas Hope with the construction of a mansion in place of the castle at Kerse. It represents Sir Thomas Hope’s arms, a chevron between three bezants, impaled with those of his wife, three bucks’ heads. She was Helen Rae, daughter of Alan Rae of Pitsendie. It would not be unusual for a new owner to undertake new building work and to commemorate it in this fashion. Porteous was able to be more precise, for in the diary of Thomas Hope on 31 May 1642 he mentions having written to his son telling him “to haist him home for Kerse, for the house bigging bi James Murray.” (Porteous 1972, 43).

However, Fleming was wrong in assuming that the tower had been demolished to make way for the new mansion. Instead, the old building was modified to make it visually more modern, and an extension was added to the north. The extension was 8.2m long and its walls averaged 0.6m wide. It was probably only of two storeys with a dormered attic. Three splayed windows on the ground floor faced west and presumably were mirrored by windows on the floor above. This was the main façade, though the entrance was from the east. A doorway was also cut through from the old block.

It may have been at this time that a second north/south ditch, 5.9m wide and 1m deep, was dug to the west of the earlier ones to divert water northwards into the River Carron. This would have allowed elements of the “moat” to have been infilled.

Thomas Hope did not get long to enjoy his new house and died in August 1643 leaving it to his son, also called Thomas. A charter of confirmation made just a month before he died granted the burgh of barony, that is Eastend, an annual fair to be held on 15 August. The Hopes also had the right to have ferries across the River Carron. As fate would have it Thomas junior did not have it much longer and upon his death it went to his brother, Alexander, c1648. Alexander Hope was created the first baronet of Kerse in 1672. It was in the hands of his son, also Alexander, when in 1707 Robert Sibbald wrote: “Carse Castle the Seat of Sir Alexander Hope, where, besides the Tower are fine low Buildings with Gardens and Inclosures.”

The river continued to alter its course and cause damage to adjoining properties. In 1672, for example, the Scottish Parliament made an abatement to William Bruce of Newton (St Martin’s) of the feu duty of his lands on the other side of the river from Kerse as part of them

“was washen and taken away thereof by the impetuous running of the rivers of Forth and Carron the number of six oxengait half oxgait ane aiker and three quarters of [ane] aiker”

(Bailey 1992, 52).

To the west of Kerse a large meander had been migrating eastwards and by 1719 threatened to inundate the mansion. Consequently

“for preserving the house (commonly called Castle) of Kerrs, which was near undermin’d by the river of Carron, the course of the said river was changed by cutting throw some necks of land, which occasioned the dividing of Bothkennar”

(Johnston 1723).

The grounds were well looked after and the Caledonian Mercury of 28 May 1741 mentions a pigeon house belonging to Sir Alexander Hope.

The fourth baronet racked up huge debts and these probably forced the judicial sale of the state of West Kerse in December 1747. The purchaser was Lawrence Dundas. He had made a fortune out of supplying the government army in Scotland with provisions following the 1745 rebellion.

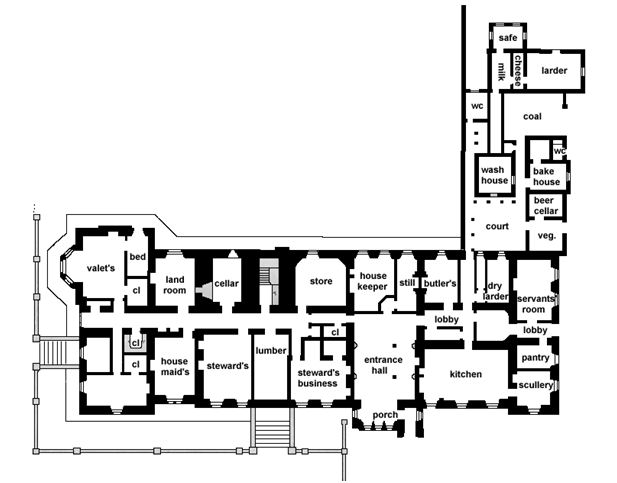

He soon spent part of that fortune improving the house at West Kerse. The old tower house, despite the modifications made to it, was rather restricting and an extension which almost doubled the ground plan was placed to its east. This extension incorporated the new entrance which lay on the first floor – probably reflecting the earlier arrangement. A large earth embankment was placed in front of this providing a ramped terrace and partly obscuring the ground floor from that side.

The eastern extension produced an almost square ground plan, 18m wide, as shown on Roy’s map of 1755. The problems of building on the damp clay were evidently recognised as the walls were much narrower and so carried less weight. The foundations of the new house were only 0.3m deep but were set on a raft of wood and stone slabs and two courses of bricks. A layer of slate then separated the brick base from the stone wall above. The first course on the outer face comprised projecting stone blocks with chamfered tops. At basement level four windows faced east; on the first floor the corresponding windows had the main entrance doorway in the centre, and on the upper two floors there were five windows, presenting an imposing symmetrical façade.

To the north of the 17th century extension another square block was added shortly afterwards incorporating outhouses from earlier. This was built with conventional foundations and appears to have been a servant’s wing with offices. It was only one or two storeys in height and on the east side it created a small courtyard between it and the main house.

Lawrence Dundas was one of the main promoters of the Forth and Clyde Canal and became its first chairman. It was largely due to his influence that the eastern terminus of the Great Canal, as it came to be called, was placed at Grangemouth. Construction work began at the east end and on 10 July 1768 he cut the first turf of this significant project in his own grounds. The line of the canal took it from the Grange Burn on a westerly course, just to the north of the home farm known as “End of Town” or “Barns” and on past Kerse House. It thus came to form the northern boundary of its policy or pleasure grounds – the towpath was on the north side.

These grounds were laid out afresh. A boundary wall led westward from this north wing defining the lawn to its south. 50m along this wall and a little to its north was an ornate ice-house. Its architectural features suggest a date of 1760-1780. It consisted of a domed cylindrical chamber made of two brick walls separated by an insulation gap. The inner wall displayed English Bond and was 3.7m in diameter. Attached to the north side of this was a vaulted brick porch and access between them was through a rectangular hatch raised o.6m above the porch floor. This suggests that the floor of the inner chamber was also raised, as would have been necessary at this location. The stone façade of the porch was finished with reticulated rustication bordered by roll moulding, set on a fluted plinth course (Bailey 1992, 43-44).

The ice-house was probably built at the same time as the new walled garden located well to the west of the house, effectively screening it from the high road. The surrounding 3m tall wall was made of brick with 1m wide indented dressed stone pillars at 10.5m intervals. The date “17.7.77” is neatly inscribed on the outside of one of the dressed stone piers, along with a much fainter “IT 1772,” obscured by later graffiti. Another pillar bore a graffito of 1780. The heavily moulded keystoned eastern gateway would by typical of this period. In plan the garden was not rectangular but broadened out to the south by a graceful sinuous curve on its east side. To its north was an orchard.

Illus 13: Left – Pillar with graffiti; right – Eastern Gateway to Walled Garden.

Estate Plans (eg. RHP 48368 & RHP 80394) show a series of winding paths connecting the house to the “kitchen garden” and the entrance lodge. A broad waterway or fish pond also extended along the south side of the walled garden, continuing along its eastern side as a channel. Whilst this replaced the two earlier north/south channels to the east, that following the old course of the Almond Pow was still there as a lined “canal.” The wooded area north of the boundary wall connecting the house to the walled garden was labelled “back park” on the plans, with the open ground to the south as “bowling green.” The paths from the house to the walled garden crossed the water feature at two points by short bridges. The Estate Plan also shows a ‘melon ground’ in the southeast corner of the garden, with a long building astride the south wall. The Hope sundial was placed in front of this garden building (its present whereabouts is not known).

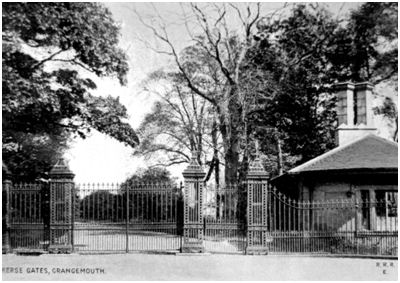

The drive followed the curving edge of the woodland from the east side of the house to the gateway beside the lodge opposite to the Falkirk Road. This lodge reflected the glory of the house and had tall chimney stacks set diagonally to the walls. A large picture window provided a good view of anyone approaching and the door lay alongside the drive. The cast and wrought iron gateway was a well-known feature in the landscape and gave its name to the road intersection – the Earl’s Gates.

Lawrence Dundas’s business concerns continued to expand and from 1764 until 1777 he was the Governor of the Royal Bank of Scotland. His official status also grew. In 1762 he was made a baronet and in 1766 he bought the lands and earldom of the Orkneys and Shetlands for £63,000. In 1763 the architect John Adam was asked to come up with designs to aggrandise Kerse House and these can now be seen in the collections of the RCAHMS. They show a huge Palladian style mansion using the existing square four-storey tower as its hub. From this curved corridor wings ending in two-storey piended pavilions would have formed an open court to the east. The main door would have been approached by a broad stair which hid the lower floor from view. The west façade would have been straight and the two end bays displayed large Venetian windows. It was never built. Lawrence Dundas had properties in Edinburgh and elsewhere. Aske Hall in Yorkshire became the family’s principal residence.

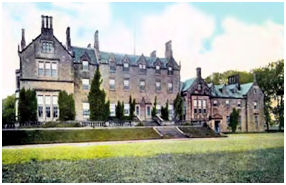

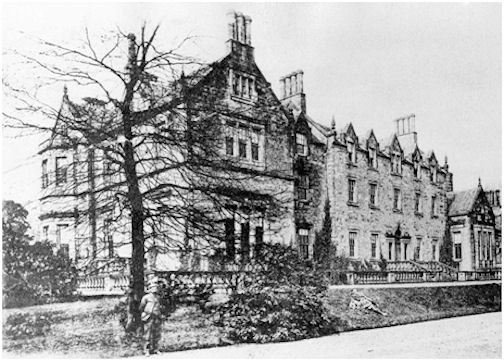

Lawrence Dundas died in 1781 leaving a huge fortune. He was succeeded by his son, Sir Thomas, who was raised to the peerage in 1794 as Baron Dundas of Aske. He too became the Governor of the Forth and Clyde Canal Navigation Company and it was he who commissioned William Symington to experiment with the use of steam on craft using the canal. Thomas Dundas was succeeded in 1820 by his son, Lawrence, who commissioned a remodelling and southern extension to the house by architect John Tait, completed in 1831 (RHP 80026). The southern extension was substantial – its east gable projected beyond the face of the existing buildings to form a frame to them. The south façade included a large bay window set within a gablet towards its west end. The earth embankment that had led to the main eastern entrance was extended around the south side to provide access to an entrance there.

At the same time a smaller gable was advanced in the court between the main block and the servants’ wing. This provided a counter-balance to the south wing, its diminutive scale in keeping with the lower height of the buildings there. The style is often described as weak Elizabethan. The raised earth terrace with its flights of steps and stone balustrade became a dominant feature.

Illus 20: Two views of Kerse House looking west, c1905.

In the grounds the pond was retained for another decade or two and was used by the Zetland Curling Club in the 1840s. Thereafter it was filled in. The gradual raising of the ground level in the vicinity of the house, combined with improved subterranean drainage, meant that such expanses of water were no longer necessary. When Fleming wrote in 1902 he stated that “The extensive gardens, including this site, are entirely surrounded by a wide moat 40ft. broad, and having the depth of 4 feet, now dry; but a burn runs close by, whose waters probably were formerly used to fill it.” Parts were still visible in the 1960s.

The extensive grounds of the house were kept in pasture for many decades and let every few years. The 80 or so acres provided grazing for dairy cows, supplying milk to the rapidly growing population of Grangemouth. In 1839 the death of the Kerse House milk pony, called Donald, hit the headlines across Britain. It was not a dramatic death, indeed death was due to extreme old age, but the faithful character of this animal had endeared him to the local people. Donald did the milk round every day of the week except the Sabbath and did not need guidance. He even went to the farrier of his own accord whenever a horseshoe required work. The pasture was also used to fatten up cattle bought cheaply at the Falkirk Trysts. James Duncan, forester on the estate of the Earl of Zetland, was returning to Kerse House from the Tryst in October 1872 with a herd of cattle when he dropped down dead in Dalderse Avenue.

The shape of the estate in 1884 was completely different to that of the late feudal period. An agricultural account of Stirlingshire published in that year gives us an idea of its nature:

“On this estate are many good specimens of carse farms. Kerse House is in the centre of the carse, and the well-wooded park is let for grazing at £370 a year. The highest rent paid for one farm is £380, by Mr John Thomson for Carronflats, Painshead, and part of Inch. Mr Robert Buchan has Dalgrain, rented at £190, and Kerse Mains at £204; Mr Alexander Simpson has West Mains and East Thorn, 100 Scotch acres, at £290; and Mr Marshall has Fouldubs at £262, 10s., and Mary-flatts at £85. In the county valuation roll there are in Falkirk parish above 140 subjects, of which Lord Zetland is entered as proprietor; but the great majority of them are comparatively small holdings at Grangemouth, and hardly more than twenty of them are farms, three or four of which have corn mills attached. Most of the farms on the estate are let for about or under £200 a year.”

The Dundas family were now spending most of the year at Aske House, with a round of visits to their many other properties. Kerse House remained its principal Scottish residence, but they were only in occupancy for two or three weeks a year in the late summer. When in residence they would visit the Free Church, of which they were great patrons. They also conducted numerous other duties, seeing tenants, opening events or buildings. One of the last garden parties at Kerse House in August 1894 was for the tenants of Kerse, Castlecary, Clackmannan and Fife as well as some of the leading citizens from Grangemouth. There was a tradition of abstinence from alcohol in the family and each year they welcomed the visits of hundreds of juvenile abstainers from the area to the grounds of Kerse House, often providing fruit and refreshments. For most of the year the estate was run by the factor and Dundas Lodge, now the Grange Manor, was built to accommodate him. Factors down the years included Andrew Longmoor, James Newton and Charles Brown.

When not in residence the family made the house available to its friends and more distant relatives to use. In September 1862, for example, Lord Stratford de Redcliffe occupied Kerse House for two weeks during which time he was visited by the Turkish Ambassador and several noblemen of note. Redcliffe had served as British Ambassador at Constantinople. In August 1875 Lord and Lady Kilmarnock stayed at Kerse House after their wedding; she was the cousin of the Earl of Zetland.

The Marquis of Zetland last stayed in Kerse House in 1897. Two years later he placed it at the disposal of the Provost of Glasgow and a committee for lodging wounded soldiers and sailors from the Boer War there during their convalescence. The offer was widely reported, but does not seem to have been taken up. It was clear that the house would not be used any more by the Dundas family and in 1910 Grangemouth Town Council started negotiations with Charles Brown to lease the policy of Kerse House as a public park. The sum of £60 annually was put forward, on top of which there would have been maintenance costs. That September market gardeners were informed that the garden extending to 4 acres, with the lodge and such ground outside the garden walls as may be arranged, were available to let.

Up until this point the main road from Falkirk had approached the entrance gateway to Kerse from the west. It then divided in two, the northern branch heading for the crossing of the Forth and Clyde Canal where there was a circular toll house. The south arm went to Beancross, with a road off to Grangemouth. At the corner of the latter two was an older tollhouse which became incorporated into Kerse Estate. For decades there had been a temptation for the locals on foot to take a shortcut across the grounds of Kerse House. Such had, for instance, been the case in January 1865 when 60 year old Christina Wilkie, on her way back to Falkirk, collapsed against one of the trees having drunk too much alcohol. That night it snowed and her body was found three weeks later by James Duncan the overseer at Kerse House.

Just after the turn of the century a new road was put in to Grangemouth to continue that from Falkirk and the new crossroads became quite busy.

The Marquis of Zetland had decided that his connection with the ancestral home was to be ended and by 1911 he was well down the legal process required to permit him to sell it:

“INTIMATION IS HEREBY GIVEN, That THE MOST HONOURABLE LAWRENCE DUNDAS, MARQUIS OF ZETLAND, K.T., Heir of Entail in possession of the Entailed Lands and Estates of Kerse and others situated in the Counties of Stirling, Clackmannan, Fife, and Linlithgow, has presented a PETITION to the LORDS of COUNCIL and SESSION (First Division – Junior Lord Ordinary, Mr Paterson, Clerk) in terms of “The Lands Clauses Consolidation (Scotland) Act 1845” and the Entail Statutes, and relative Acts of Sederunt, for authority to uplift and acquire in fee-simple the consigned Sums of £908, £53 7s 6d, £30, £172 17s 9d, £6390, and £2005, mentioned in the Petition; and also for authority to demolish Kerse House, and sell or otherwise dispose of the materials thereof. Date of Interlocutor ordering intimation, 23rd March 1911.”

(FH 25 March 1911, 1).

The legal system, however, was slow to conclude. When the First World War broke out the Marquis of Zetland again offered to place the empty house at the disposal of the country and stated that he would equip it as a hospital at his own expense for the care of the wounded. Some medical material was acquired, but at that stage in the war there was a great overprovision of such accommodation and the authorities diverted the resources elsewhere. In 1923 the Dundee Courier noted that the unoccupied Kerse House “is now unfortunately almost a ruin” (29 November 1923, 8).

In 1919 a new company called Scottish Dyes acquired an option to buy 80 acres of West Kerse at £8 an acre. The first part of the works was built to the south of the new road, Kerse Road, in 1919. By 1930 the whole land, including the policy and house, had been bought. In 1948 an additional area to the east of the house was also taken to allow for future expansion. From the beginning the firm allowed its employees to walk through the grounds of the old house and gave permission for local organisations to hold events there. In 1923 the first of many annual athletic sports days for Scottish Dyes was held there. In September 1929 a garden fete was held in grounds of Kerse House to raise money for the hall of Kerse Church. Despite having sold the grounds, it was opened by the Marquis of Zetland who donated 25 sovereigns.

1928 saw Scottish Dyes being taken over by ICI. Safety at the factory was ramped up and greater provision was made for recreation. In that year a grass tennis court was laid out in the grounds of Kerse House. A Recreation Club was established and within five years there were four tennis courts as well as hockey and football pitches all set within a landscape of mature trees. In 1932 the club organised the first children’s gala days in the grounds and these became a highlight of the calendar.

The following year, in July 1933 anew purpose-built clubhouse was officially opened, and despite the change in ownership was still known as the Scottish Dyes Recreation Club. It had a large dance hall, a games room for snooker and darts, a lounge and a bar with a drinks licence. It was placed astride the south wall of the walled garden and in style resembled an orangery. Murdoch and Son of Stenhousemuir were the contractors and stone from the demolished house that had been stored in the area was taken to Grangemouth at the request of St Mary’s Episcopalian Church, where in 1937 it was used to construct the new church building. A badminton hall and gymnasium were erected in the former walled garden. On one of his rare visits to Scotland, in May 1938, the Marquis of Zetland now entertained his tenants from Grangemouth, Castlecary and Clackmannan in the new club. Over the decades since then the 30 acres site was enhanced with a badminton hall, a fitness track and a full-sized cricket pitch. The latter closed in the 1990s. The clubhouse closed in 2008, partly due to concerns over safety regulations and partly due to shifting patterns of use resulting from the reduction in the workforce at the chemical works.

Those parts of the estate belong to ICI which were not required for manufacturing or for the recreation grounds were leased to a dairy farmer for grazing in the 1930s. The lodge at the Earl’s Gates was sold to Stirlingshire County Council and was demolished as part of the road improvements.

During the Second World War the Recreation clubhouse was used as the base for Number 15 Platoon (ICI Works), D Company, III Stirlingshire Home Guard. An Auxiliary Bomb Disposal Unit was attached to the platoon and one of their practical exercises involved digging deep holes around Kerse House, shoring them up, and then filling them in again. When it came to laying explosives the Home Guard got to practise on the ruins of the house. The ruins were also used by the Auxiliary Fire Service to practice its skills. By 1941 a rescue training school was established at Kerse House teaching recruits how to get people out of “bombed out” buildings. Always innovative, the Grangemouth men devised a new method of lowering stretcher-bound victims from the roofs of such structures and demonstrated them there. Sir Steven Bilsland, the district commissioner of Civil Defence, reckoned it was the finest such school in Scotland. In October 1944 the final of a regional completion which involved 165 teams was held at Kerse House and was won by men from Kilmarnock.

In 1902 Fleming had noted that the name of Kerse House had been changed to Zetland House, though he seems to have been almost alone in this. In the 1940s Kerse House was occasionally referred to as Zetland House, though strictly speaking that was the Dundas family house on Shetland. The demolition of Kerse House was gradual. In 1937 stone from it was used in St Mary’s Church, further destruction occurred during the war, and in 1957 most of the remainder was levelled. However, it was not until 1984 that the final section was taken down. Even then the basement remained hidden below ground until 2012.

In 2011 the site was acquired for the Asda supermarket chain and was earmarked for redevelopment as a distribution centre. An archaeological excavation was conducted in 2012 by Headland Archaeology and the following year the entire site – mature trees, historic garden and ancient tower house – was levelled with no regard for the retention of any of the elements of the past.

Sites and Monuments Records

| Kerse House | SMR 792 | NS 9155 8163 |

| Kerse House Doocot | SMR 30 | NS 9185 8206 |

| Kerse House Ice-house | SMR 65 | NS 9152 8169 |

| Kerse House Lodge | SMR 2036 | NS 9134 8128 |

| Kerse House Stables | SMR 1055 | NS 915 819 |

| Kerse House Sundial | SMR 1423 | NS 915 816 |

| Kerse House Walled Garden | SMR 883 | NS 914 805 |

| Kerse Toll House | SMR 2037 | NS 9147 8110 |

Bibliography

| Bailey, G.B. | 1992 | ‘Ice-houses,’ Calatria 2, 33-48. |

| Bailey, G.B. | 1992 | ‘Along and across the River Carron; a history of communications on the lower reaches of the River Carron,’ Calatria 2, 49-84, |

| Blackie, J. | 2019 | The Dyes; Scotland’s dyestuff pioneers and a century of chemical manufacturing in Grangemouth. |

| Fleming, J. | 1902 | Ancient Castles and Mansion of Stirling Nobility. |

| ‘Morwenside Parish, Slamanna, Falkirk, Bothkennar, Airth, Larbert, and Dunipace.’ | ||

| Porteous, R. | 1972 | Grangemouth’s Ancient Heritage. |

| Reid, J. | 2012 | ‘The Barony of West Kerse,’ Calatria 28, 11-46. |

| Robertson, A. | 2012 | Earls Gate Park, Grangemouth – Desk based assessment, archaeological excavation & historic building recording. |

| Sibbald, R. | 1707 | History and Description of Stirlingshire, Ancient and Modern. |

| Tait, J. | 1884 | ‘The agriculture of the County of Stirling,’ Transactions of the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland. |

| Maps | National Library of Scotland. |

G.B. Bailey (2020)